Validating Monte Carlo Models with Experimental Tissue Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of Monte Carlo (MC) models against experimental tissue data, a critical step for ensuring reliability in biomedical research and drug development.

Validating Monte Carlo Models with Experimental Tissue Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of Monte Carlo (MC) models against experimental tissue data, a critical step for ensuring reliability in biomedical research and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of MC simulation in radiation transport and tissue interaction, explores methodological applications across therapy, imaging, and dosimetry, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes robust protocols for quantitative validation and comparative analysis. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current best practices to enhance model accuracy, foster reproducibility, and accelerate the translation of computational findings into clinical applications.

The Bedrock of Accuracy: Core Principles of Monte Carlo Simulation and Tissue Equivalency

Monte Carlo (MC) simulations have become the computational gold standard in biomedical physics and engineering, providing unparalleled accuracy in modeling the stochastic nature of radiation and light transport within biological tissues [1]. Their role is critical in advancing medical imaging, radiation therapy treatment planning, and the development of new diagnostic techniques. However, the transformative potential of these methods hinges on their rigorous validation with experimental tissue data, ensuring that virtual models faithfully represent complex clinical realities. This guide compares leading Monte Carlo simulation platforms and methodologies, focusing on their performance in experimentally validated biomedical research contexts.

At its core, the Monte Carlo method is a computational technique that uses repeated random sampling to solve complex deterministic or stochastic problems [1]. In biomedical physics, it tracks the trajectories of individual particles—such as photons, electrons, or protons—as they travel through and interact with virtual models of human anatomy or medical devices.

A significant challenge in MC simulations is the high computational cost required to achieve statistically meaningful, low-noise results [2] [3]. This has driven the development of advanced acceleration strategies, which fall into two primary categories:

- Algorithmic & Hardware Acceleration: This includes scaling and perturbation methods that reduce the number of required simulations [2], and the use of Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) parallel computing. GPU-based MC platforms can achieve speedups of 100 to 1000 times over traditional Central Processing Unit (CPU) implementations, making large-scale simulations clinically feasible [4] [3].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Integration: Deep learning models are now being used as surrogate models to predict MC dose distributions in seconds, and to denoise results from shorter simulation runs [5] [1]. AI also leverages MC-simulated synthetic data for training, creating a powerful synergistic relationship [1].

Comparative Analysis of Monte Carlo Simulation Platforms

The following tables provide a detailed comparison of general-purpose and specialized MC simulation packages, highlighting their key characteristics and performance in experimentally validated scenarios.

Table 1: Comparison of General-Purpose Monte Carlo Simulation Platforms

| Platform/Toolkit | Primary Applications in Biomedicine | Key Features & Strengths | Documented Experimental Validation & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEANT4 [6] [3] | Proton therapy [3], brachytherapy dosimetry [3], general particle transport | Models complex geometries [3]; extensive physics models for particle interactions [3]. | Used as the engine for GATE, which is validated in dosimetry studies (e.g., 3D-printed phantom simulations) [6]. |

| GATE [6] [1] | PET, SPECT, CT simulation [1], radiation therapy [1] | User-friendly interface for GEANT4 [1]; simulates time-dependent processes (e.g., organ motion) [3]. | Validated for dosimetric accuracy in radionuclide therapy; showed PLA phantom dose difference of +1.7% to +5.6% in liver [6]. |

| EGSnrc [3] | External beam radiotherapy dosimetry [3] | High accuracy in electron and photon transport [3]; widely validated for clinical dosimetry [3]. | Considered a benchmark for dose calculation accuracy; however, can be computationally expensive [3]. |

| MCNP [3] | Radiation shielding, neutron therapy [3] | General-purpose code for neutron, photon, and electron transport [3]. | Applied in various diagnostic and therapeutic contexts [3]. |

| FLUKA [3] | Heavy ion therapy [3] | Robust nuclear interaction models [3]. | Valued for modeling nuclear interactions in therapeutic applications [3]. |

| TOPAS [3] | Proton therapy [3], adaptive treatment planning [3] | Customized for medical physics on top of GEANT4; high efficiency and ease of use [3]. | Popular in proton therapy research and planning [3]. |

Table 2: Performance of Specialized and Accelerated Monte Carlo Methods

| Method / Platform | Specific Application | Key Performance Metrics | Validation against Experiment/Independent MC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaling Method for Fluorescence [2] | Fluorescence spectroscopy in multi-layered skin tissue | Achieved 46-fold improvement in computational time [2]. | Mean absolute percentage error within 3% compared to independent MC simulations [2]. |

| GPU Acceleration [4] | General tomography (CT, PET, SPECT) | Speedups often exceeding 100–1000 times over CPU implementations [4]. | Provides essential support for developing new imaging systems with high accuracy [4]. |

| Deep Learning (CHD U-Net) [5] | Predicting MC dose in heavy ion therapy | Gamma Passing Rate up to 99% (3%/3mm criterion); prediction in seconds [5]. | Improved Gamma Passing Rate by 16% (1%/1mm) vs. traditional TPS algorithms [5]. |

| MCX-ExEm Framework [7] | Fluorescence in 3D-printed phantoms | Captured nonlinear quenching, depth-dependent attenuation accurately [7]. | Strong agreement across parameters; minor deviations in low-scattering/absorption regimes [7]. |

Experimental Validation Protocols

Validating MC simulations against controlled experimental data is crucial for establishing their credibility in biomedical research. The following are detailed methodologies from key studies.

Validation of Fluorescence Simulations with Solid Phantoms

This study aimed to validate a GPU-accelerated, voxel-based fluorescence MC framework for applications like fluorescence-guided surgery [7].

- Objective: To experimentally validate the MCX-ExEm framework's ability to model fluorescence under varying fluorophore concentrations, optical properties, and complex 3D geometries [7].

- Materials:

- Procedure:

- The optical properties (absorption, scattering) and fluorophore concentrations of the phantoms were precisely characterized [7].

- Experimental fluorescence measurements were obtained by imaging the phantoms [7].

- Simulations were run using the MCX-ExEm framework with the same parameters [7].

- The simulated and experimental fluorescence intensities were compared across all tested parameters, including quenching at high concentrations and depth-dependent effects [7].

- Outcome: The study demonstrated strong agreement between simulations and experiments, establishing a foundation for "fluorescence digital twins." Minor deviations occurred primarily where optical characterization was most challenging (e.g., low-scattering regimes) [7].

Dosimetric Validation Using 3D-Printed Phantoms

This research evaluated the dosimetric accuracy of 3D-printed materials (PLA and ABS) compared to real tissues in radionuclide therapy using MC simulations [6].

- Objective: To determine if 3D-printed PLA and ABS phantoms can accurately mimic real tissues for pre-treatment dosimetry in radioembolization [6].

- Materials:

- Procedure:

- The geometry was simulated with materials defined as PLA, ABS, and real organ densities (liver: ~1.06 g/cm³, lung: ~0.26-0.35 g/cm³) [6].

- An activity of 1 mCi of Tc-99m or Y-90 was placed in the tumor mimic [6].

- A DoseActor recorded the energy deposition (dose) in the liver and lung volumes [6].

- The dose distributions for PLA and ABS were compared to the dose in real organ densities to calculate percentage differences [6].

- Outcome: For Y-90, PLA showed a +1.7% dose difference in the liver, indicating it is highly suitable for representing high-density tissues. ABS showed large differences in the lungs (-34% to -35%), making it less suitable for very low-density tissues [6].

Validation of a Scaling Method for Fluorescence Spectroscopy

This work introduced a scaling method to accelerate MC simulations of fluorescence in multi-layered tissues with oblique illumination, a previously unsolved challenge [2].

- Objective: To develop and validate an efficient scaling MC algorithm for fluorescence simulation in multi-layered tissue models with oblique probe geometries [2].

- Materials:

- Procedure:

- Baseline Simulations: A single set of photon histories was generated at excitation and emission wavelengths for a baseline tissue model [2].

- Scaling: For a new set of optical properties, the recorded photon histories were scaled using multi-layered scaling relations, rather than running entirely new simulations [2].

- Comparison: The detected fluorescence intensity from the scaling method was compared against the results from independent, traditional MC simulations [2].

- Outcome: The scaling method achieved a 46-fold improvement in computational time while maintaining a mean absolute percentage error within 3%, demonstrating high accuracy and efficiency [2].

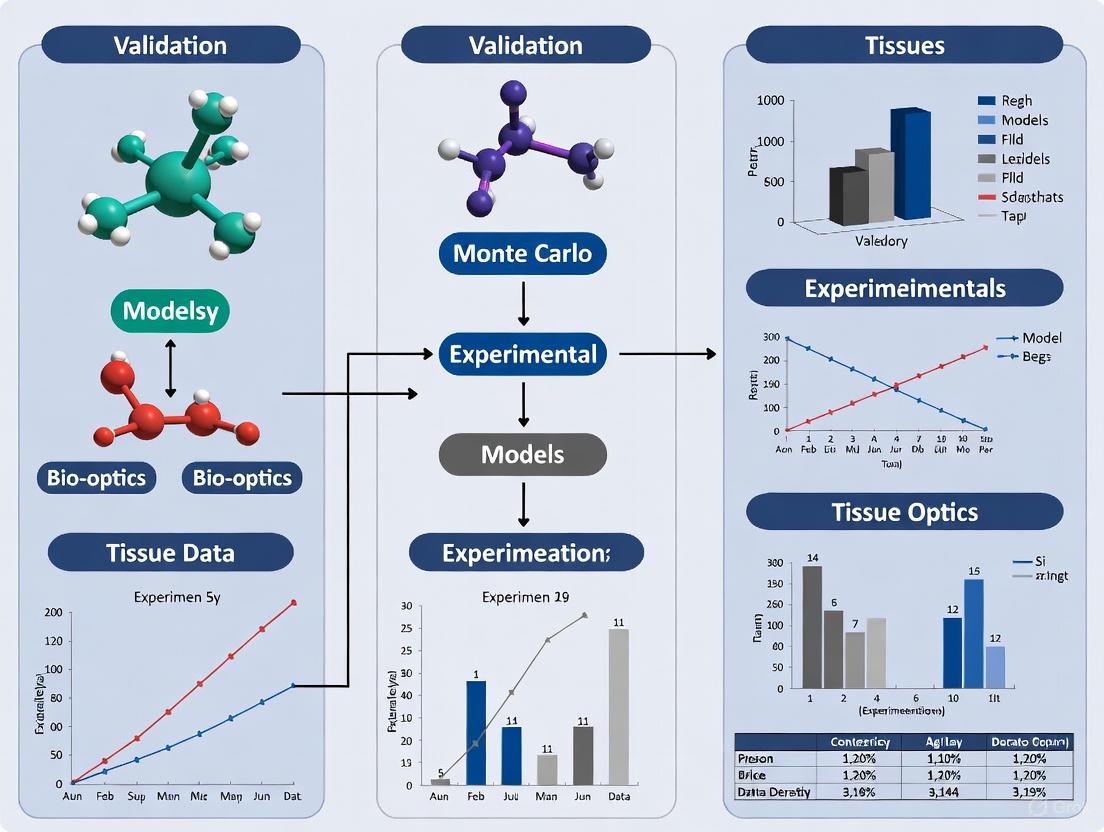

Research Workflow and Platform Selection

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for conducting and validating a Monte Carlo study in biomedical physics, integrating the key concepts of acceleration and validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table details essential materials, software, and reagents used in the featured experiments for MC simulation and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MC Validation

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| 3D-Printed Phantoms (PLA, ABS) [6] [7] | Serve as physical models with known geometry and material properties to mimic human tissues and validate simulations. | Dosimetric validation in radionuclide therapy [6]; creating complex 3D geometries for fluorescence validation [7]. |

| Well-Characterized Optical Properties (μₐ, μₛ) [7] | Define the absorption and scattering coefficients of phantoms or tissues; critical input parameters for MC simulations. | Used as input for fluorescence MC simulations and to compare against experimental results [7]. |

| Radionuclides (Tc-99m, Y-90, Lu-177) [6] [8] | Act as radiation sources for simulating and validating internal dosimetry in diagnostic and therapeutic applications. | Simulating dose distribution from a tumor in radioembolization [6] [8]. |

| GATE/GEANT4 MC Platform [6] [3] [1] | A widely adopted software toolkit for simulating radiation transport in medical imaging and therapy. | Dosimetry studies in nuclear medicine [6]; simulating PET and SPECT systems [1]. |

| GPU Computing Cluster [4] | Provides massive parallel processing power to accelerate MC simulations, reducing computation time from days to hours or minutes. | Enabling practical, large-scale MC applications in tomography that are not feasible with CPU-based codes [4]. |

| DoseActor (in GATE) [6] | A sensitive detector component in MC simulations that records energy deposition (dose) in a defined 3D volume (voxels). | Calculating dose distributions in specific organs like liver and lungs from a simulated radionuclide source [6]. |

The Critical Role of Tissue-Equivalent Materials and Phantoms in Validation

In the field of medical physics and radiation research, the validation of computational models against reliable experimental data is a critical step in ensuring their accuracy and clinical applicability. This process relies heavily on the use of tissue-equivalent materials and anthropomorphic phantoms, which serve as standardized, reproducible, and ethically uncomplicated substitutes for human tissues. These tools are indispensable for bridging the gap between theoretical Monte Carlo simulations and real-world clinical applications, particularly in advanced radiotherapy techniques like proton therapy [9] [10] [11]. Without them, confident translation of novel techniques from the laboratory to the clinic would be severely hampered. This guide objectively compares the performance of various tissue-equivalent materials and the experimental protocols used to validate sophisticated Monte Carlo models, providing researchers with a clear framework for their critical work.

Performance Comparison of Tissue-Equivalent Materials

The efficacy of a phantom is fundamentally determined by the radiological properties of its constituent materials. Researchers have developed and characterized a wide array of materials to simulate biological tissues.

Table 1: Performance of Tissue-Equivalent Materials for Mouse Model Phantoms

| Tissue Type | Optimal Material Formulation | Measured Density (g/cm³) | CT Number (HU) | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Polyurethane-Resin (1:1.3) [12] | 0.53 | -856.4 ± 46.2 | Low density, low effective atomic number (Zeff). |

| Soft Tissue | Resin-Hardener (1:1) [12] | 1.06 | 65.3 ± 8.4 | Matches electron density and attenuation of soft tissue. |

| Bone | Resin with 30% Hydroxyapatite [12] | 1.42 | 797.7 ± 69.2 | High density and Zeff due to calcium content. |

For ultrasound imaging, material requirements shift from radiological to acoustic properties. A systematic analysis identified that water-based materials most closely align with the needs of ultrasound phantoms, with Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) being a standout material for its ability to match the acoustic properties of various human tissues [13].

Table 2: Tissue-Mimicking Materials for Ultrasound Phantoms

| Material Category | Example Materials | Acoustic Properties | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water-Based | Agar, Gelatine, PVA, Polyacrylamide (PAA) [13] | Speed of Sound: 1425-1956 m/s [13] | General ultrasound; PVA matches many human tissues best. |

| Oil-Based | Paraffin gel, SEBS copolymers [13] | Speed of Sound: ~1425-1502 m/s [13] | Specialized applications requiring specific elastic properties. |

| Oil-in-Hydrogel | Agar/Gelatine with Safflower Oil [13] | Attenuation Coefficient: 0.1-0.59 dB/MHz/cm [13] | Creating heterogeneous tissue models. |

Experimental Validation of Monte Carlo Models: Protocols and Data

The true test of a Monte Carlo model lies in its validation against controlled physical experiments. The following case studies illustrate this critical process.

Protocol 1: Proton Range Verification with a Dual-Head PET System

- Objective: To validate a GATE Monte Carlo model for verifying proton beam range using an in-beam dual-head PET (DHPET) system by comparing simulated data against experimental measurements [9].

- Experimental Setup: A phantom (either HDPE or gel-water) was irradiated with monoenergetic proton beams. The resulting positron-emitting isotopes were detected by the DHPET system to determine the activity range and compare it to the proton's physical range [9].

- Monte Carlo Models Compared: The study evaluated three different nuclear models for predicting β+ isotope production:

- GEANT4 QGSP_BIC: A theoretical built-in hadronic physics model.

- EXFOR-based: Utilizes tabulated experimental cross-section data.

- NDS (Rodríguez-González et al.): An updated, optimized cross-section dataset [9].

- Performance Comparison:

- Dose Distribution: All models showed excellent agreement with the clinical treatment planning system (RayStation), with mean range deviations within ±0.2 mm [9].

- Activity Range Prediction: In a gel-water phantom, which more closely mimics human tissue, the NDS model demonstrated superior accuracy, closely matching the experimental data. The QGSP_BIC model underestimated the distal range by 2-4 mm, while the EXFOR model showed a slight overestimation [9].

This workflow from simulation to experimental validation is summarized below.

(caption: Workflow for Monte Carlo model validation in proton therapy)

Protocol 2: Prompt Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy for Proton Therapy

- Objective: To develop and validate Monte Carlo codes (GEANT4, MCNP6, FLUKA) for Prompt Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy (PGS), a real-time method for monitoring proton beam range [10].

- Experimental Setup: A PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) block phantom was irradiated with protons of energies from 90 to 130 MeV. The resulting prompt gamma-rays were detected using a CeBr3 scintillator detector to obtain reference PGS spectra [10].

- Monte Carlo Models Compared: The study compared the performance of three major Monte Carlo codes in reproducing the experimental gamma-ray spectra.

- Performance Comparison:

- GEANT4 was the only code capable of successfully reproducing most prominent prompt gamma lines [10].

- FLUKA aligned better with experimental data for mid-range energies but overestimated the 4.44 MeV gamma line at higher energies [10].

- MCNP6 provided the closest match for the 4.44 MeV line at higher energies [10].

- All codes failed to accurately reproduce the 6.13 MeV oxygen de-excitation line, highlighting a universal limitation in existing nuclear data tables and underscoring the need for continued experimental research [10].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A well-equipped laboratory for phantom development and model validation requires a suite of specialized materials and instruments.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Phantom Fabrication and Validation

| Category | Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Base Materials | Polyurethane, Epoxy Resin, Hydroxyapatite, Montmorillonite Nanoclay [12] | Primary components for constructing tissue-equivalent phantoms with tunable densities. |

| 3D Printing Mat. | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), VeroClear, Rigur, Accura Bluestone [12] | Used in additive manufacturing to create anatomically accurate phantom geometries. |

| Attenuators/Scatterers | Titanium Dioxide (TiO2), Aluminum Oxide (Al2O3), Graphite, Glass Microspheres [13] | Added to base materials to fine-tune acoustic and radiological properties like attenuation. |

| Standard Phantoms | Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Blocks [10], ATOM Anthropomorphic Phantom [14] | Commercially available phantoms for system calibration and out-of-field dose measurement. |

| Detection Systems | Dual-Head PET [9], CeBr3 Scintillator [10], Thermoluminescent Dosimeters (TLDs) [14] | Instruments for capturing experimental data on radiation dose and isotope production. |

The critical role of tissue-equivalent materials and phantoms in validation is unequivocal. Quantitative comparisons reveal that no single material or Monte Carlo model is universally superior; the optimal choice is highly dependent on the specific application, whether it's simulating lung tissue for a small animal model or validating a nuclear physics model for proton range verification. The consistent finding across studies is that validation against controlled, well-characterized phantoms is non-negotiable. It is the only process that can identify subtle but critical discrepancies in computational models, thereby ensuring their reliability and ultimately safeguarding the quality and safety of future clinical applications. As Monte Carlo techniques and therapeutic technologies continue to evolve, so too must the sophistication and accuracy of the phantoms used to validate them.

Within the field of medical physics and radiation dosimetry, the accurate validation of Monte Carlo (MC) models relies on precise data concerning the radiological properties of both biological tissues and substitute materials. These properties—linear attenuation coefficients, stopping power, and interaction cross-sections—dictate how radiation travels through and deposits energy in matter. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key properties across real tissues and commonly used tissue-equivalent materials, framing the data within the essential context of experimental validation for MC simulations. The convergence of experimental phantom studies and computational modeling forms the foundational thesis of modern, accurate radiological science.

Comparative Analysis of Radiological Properties

The performance of tissue-equivalent materials is quantified by how closely their radiological properties match those of real human tissues. Deviations in these properties can lead to significant inaccuracies in MC simulations, which in turn affect medical imaging quality and radiotherapy dose calculations.

Linear Attenuation Coefficients

The linear attenuation coefficient (μ) describes how easily a material can be penetrated by a beam of radiation, such as X-rays or gamma rays. A higher value indicates the material is more effective at attenuating the radiation.

The following table compares the mass attenuation properties of various tissue-equivalent materials against their target biological tissues [15] [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Mass Attenuation Coefficients and Effective Atomic Numbers

| Material Category | Specific Material / Tissue | Density (g/cm³) | Effective Z (Zₑff) | Deviation in Mass Attenuation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Equivalent | ICRU Cranial Bone (Standard) | - | - | Reference |

| Epoxy Resin + 30% CaCO₃ | 1.65 | 11.02 | +17.4% (at 40 keV) to +1.2% (at 150 keV) [15] | |

| Teflon (for Cortical Bone) | - | - | Absorbed ~50% less than masseter muscle at 50 keV [16] | |

| Soft Tissue Equivalent | ICRU Brain (Standard) | - | - | Reference |

| Epoxy Resin + 5% Acetone | - | 6.19 | +13.7% to +5.5% [15] | |

| PMMA (for Skin, Glands) | - | - | Generally absorbed less X-rays than real tissues [16] | |

| Water Equivalent | Water (Standard) | 1.00 | ~7.4 | Reference |

| Epoxy Resin-based CSF | - | - | +3.4% to +1.1% [15] |

Stopping Power and Dose Deposition

Stopping power quantifies the rate of energy loss by a charged particle (e.g., an electron or proton) as it travels through a material. In radiotherapy dosimetry, this is directly related to the absorbed dose.

The table below summarizes the performance of common 3D-printing materials in mimicking human tissue for dosimetric studies [6].

Table 2: Dosimetric Accuracy of 3D-Printed Phantom Materials in Radionuclide Therapy

| Material | Density (g/cm³) | Radionuclide | Tissue Organ | Dose Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA (Polylactic Acid) | 1.24 [6] | Tc-99m | Liver | +5.6% [6] |

| Y-90 | Liver | +1.7% [6] | ||

| ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) | 1.04 [6] | Tc-99m | Lungs | -35.3% to -40.9% [6] |

| Y-90 | Lungs | -34.2% to -34.9% [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

The validation of MC models requires rigorous, well-documented experimental methodologies. The following sections detail protocols from key studies comparing tissue equivalents.

Monte Carlo Simulation for Dosimetric Accuracy

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the tissue equivalence of 3D-printed PLA and ABS phantoms for radionuclide therapy [6].

Objective: To evaluate the dosimetric accuracy of PLA and ABS phantoms by comparing dose distributions to those in real tissues using MC simulations.

Workflow Overview:

Key Materials and Setup:

- Software: GATE/GEANT4 MC simulation package (v8.1) [6].

- Phantom Geometry: A cubic water phantom (700 x 700 x 700 mm³) containing liver (220 x 140 x 80 mm) and lung mimics, with a 10 mm spherical tumor in the liver [6].

- Materials: Real tissues, PLA (density 1.24 g/cm³), and ABS (density 1.04 g/cm³) were defined in the material database [6].

- Radiation Sources: Tc-99m (1 mCi) for imaging and Y-90 (1 mCi) for therapy simulations [6].

- Dosimetry: Dose was scored using a

DoseActorsegmented into 3D voxels (dosels). The dose distribution along anatomical planes was calculated and compared using C++ analysis code [6].

X-Ray Absorption in Tissue-Equivalent Polymers

This protocol outlines a method for validating tissue-equivalent materials using X-ray absorption studies, based on a study of mandibular tissues [16].

Objective: To compare the X-ray absorption of real mandibular tissues and their tissue-equivalent polymeric materials across a diagnostic energy range.

Workflow Overview:

Key Materials and Setup:

- Software: PHITS (Particle and Heavy Ion Transport code System) MC simulation program [16].

- Phantom Geometry: A detailed mandibular model with anatomical layers (skin, gland, muscle, bone). The thicknesses of real tissues and equivalent materials were carefully matched [16].

- Materials:

- Radiation Source: X-ray photons with energies from 50 to 100 keV in 5 keV increments, simulating a panoramic dental X-ray setup [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section catalogs essential reagents, materials, and software used in the featured experiments, providing a quick reference for researchers designing similar validation studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Radiological Validation

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples from Research |

|---|---|---|

| PLA (Polylactic Acid) | 3D-printing material for phantoms simulating high-density tissues [6]. | Represents liver tissue; shows +1.7% to +5.6% dose difference [6]. |

| ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) | 3D-printing material for phantoms simulating low-density tissues [6]. | Represents lung tissue; shows ~ -35% dose difference [6]. |

| Epoxy Resin Composites | Customizable tissue substitute for various tissue types [15]. | Mimics cranial bone, brain, CSF, and eye lens with low deviation from ICRU standards [15]. |

| PMMA (Polymethyl Methacrylate) | Common tissue-equivalent polymer for soft tissue and dosimetry phantoms [16]. | Used to simulate skin, parotid gland, and other soft tissues in mandibular model [16]. |

| Teflon (Polytetrafluoroethylene) | Polymer used as a bone-equivalent material due to its higher atomic number [16]. | Simulates cortical bone in mandibular X-ray absorption studies [16]. |

| GATE/GEANT4 | Monte Carlo simulation platform for modeling particle transport in matter [6]. | Used to simulate radiation transport and dose deposition in radionuclide therapy [6]. |

| PHITS | General-purpose Monte Carlo code for simulating particle and heavy ion transport [16]. | Used to model X-ray absorption in a complex mandibular geometry [16]. |

| DoseActor | A sensitive detector within MC codes that records energy deposition in a defined volume [6]. | Used to voxelize geometry and score radiation dose for comparison [6]. |

Monte Carlo particle transport codes are indispensable tools in research and drug development, enabling high-fidelity simulations of radiation interactions with matter. Validating these simulations against experimental data, particularly with biological tissues and tissue substitutes, is a critical step for ensuring their reliability in preclinical and clinical applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of five major Monte Carlo codes—GEANT4, GATE, MCNP, PHITS, and PENELOPE—focusing on their performance and experimental validation.

Monte Carlo (MC) codes simulate the stochastic nature of radiation transport, providing insights into dose deposition, particle fluence, and nuclear interactions that are often difficult to measure directly. For research involving tissue data, the accuracy of these simulations is paramount. Validation typically involves comparing simulation results against benchmark measurements from well-characterized experimental setups, such as tissue-substitute phantoms, to quantify discrepancies in parameters like dose distribution, activity yield, or particle range.

The codes discussed here—GEANT4, GATE (which is built upon GEANT4), MCNP, PHITS, and PENELOPE (integrated into GEANT4 as a physics model)—represent some of the most widely used tools in the scientific community. Their performance varies significantly depending on the application, chosen physics models, and the specific experimental benchmarks used for comparison [17].

Comparative Performance Tables

The following tables summarize key characteristics and performance data of the major Monte Carlo codes, based on recent experimental validations.

Table 1: Overview of Major Monte Carlo Codes

| Code | Primary Developer | Notable Features | Common Applications in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEANT4 | Geant4 Collaboration (CERN) | Extensive physics models, active development, open-source [18] | Hadron therapy, space science, high-energy physics [19] |

| GATE | OpenGATE Collaboration | GEANT4-based, dedicated to medical imaging and radiotherapy | PET range verification, dosimetry, scanner design [9] |

| MCNP6 | Los Alamos National Laboratory | Legacy code, trusted for neutron & photon transport | Shielding design, dosimetry, criticality safety [20] [21] |

| PHITS | JAEA, RIST | Capable of simulating heavy ion transport | Particle therapy, accelerator design, radiation protection [22] [23] |

| PENELOPE | University of Barcelona | Precise low-energy electron & photon transport | Dosimetry, microdosimetry, X-ray spectroscopy [17] |

Table 2: Experimental Validation in Proton Therapy Scenarios

| Application / Code | Key Performance Metric | Experimental Benchmark & Result |

|---|---|---|

| Prompt Gamma (PGS) for Range Verification [20] | ||

| GEANT4 | Accuracy in reproducing PG peaks | Successfully reproduced key de-excitation lines (e.g., 4.44 MeV from Carbon-12) [20] |

| MCNP6 | Accuracy in reproducing PG peaks | Failed to reproduce key de-excitation lines [20] |

| FLUKA | Accuracy in reproducing PG peaks | Failed to reproduce key de-excitation lines [20] |

| In-Beam PET for Range Verification [9] | ||

| GATE (QGSP_BIC model) | Activity range prediction in gel-water phantom | Underestimated distal activity range by 2–4 mm [9] |

| GATE (NDS cross-sections) | Activity range prediction in gel-water phantom | Best match with experimental data; mean deviation < 1 mm [9] |

| β+-emitter Production for PET [23] | ||

| PHITS | Yield of positron-emitting nuclides | Generally underestimates yields compared to experimental data [23] |

| GEANT4 | Yield of positron-emitting nuclides | Good agreement with experimental data for carbon and proton beams [23] |

Table 3: Performance in Photon Shielding and Attenuation

| Code | Scenario | Comparison with Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| GEANT4 | Mass Attenuation Coefficient (PE/HgO composite) | Excellent agreement (e.g., 0.0843 cm²/g vs. experimental 0.0843 ± 0.002 cm²/g) [21] |

| MCNP6 | Mass Attenuation Coefficient (PE/HgO composite) | Excellent agreement (e.g., 0.0833 cm²/g vs. experimental 0.0843 ± 0.002 cm²/g) [21] |

| PHITS | Linear Attenuation Coefficient (Tissue substitutes) | High correlation with experimental data; discrepancies < 5% for most energies [22] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Validation

Validation in Proton Therapy: Prompt Gamma Spectroscopy

Objective: To validate GEANT4, MCNP6, and FLUKA for simulating proton-induced prompt gamma-ray (PG) spectra, a method for real-time range verification in proton therapy [20].

- Experimental Setup: A 130 MeV proton beam was directed onto a target. The resulting PG spectra were measured using a 15.0 cm³ CeBr₃ detector placed at 90 degrees relative to the beam axis.

- Simulation Protocol: The simulations aimed to reproduce the PG spectra from the target. Various proton data libraries, physics models, and cross-section values were employed within each code.

- Key Findings: GEANT4 was the only code capable of successfully reproducing characteristic prompt gamma-ray peaks from key elements like Carbon-12 (4.44 MeV) and Oxygen-16 (6.13 MeV). This study highlighted the critical need for updated data tables in MC simulations for nuclear physics applications in medicine [20].

Validation in Proton Therapy: In-Beam PET

Objective: To develop and validate a GATE/GEANT4 model for proton range verification using a clinical dual-head PET (DHPET) system [9].

- Experimental Setup: In-beam PET data were acquired during proton irradiation of homogeneous (HDPE) and heterogeneous (gel-water) phantoms at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan.

- Simulation Protocol: The entire process was simulated in GATE, including beam delivery, production of β+ isotopes (e.g., ¹¹C, ¹⁵O), and PET detection. Different nuclear models and cross-section datasets (QGSP_BIC, NDS, EXFOR) were evaluated.

- Key Findings: The choice of nuclear model significantly impacted accuracy. While the built-in QGSP_BIC model underestimated the distal activity range by 2–4 mm, using the external NDS (Nuclear Data Sheets) cross-section library resulted in the best agreement with experiments, with mean range deviations within 1 mm [9].

Validation for Photon Attenuation in Tissue Substitutes

Objective: To model and validate a system for measuring the linear attenuation coefficients (μ) of tissue substitute materials using the PHITS code [22].

- Experimental Setup: Ballistic gel tissue substitute samples were placed between a Ra-226 source and a NaI(Tl) detector. The detector was shielded with lead, and the source was collimated.

- Simulation Protocol: The experimental apparatus was precisely modeled in PHITS. The code simulated the transport of photons at specific energies (186.1–2204.1 keV) from the source through the samples to the detector.

- Key Findings: PHITS simulations showed a high correlation with experimental data, with discrepancies below 5% for most energies. When compared to theoretical NIST data, the differences were below 1%, demonstrating PHITS's high accuracy for modeling photon interactions in tissue-like materials [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The following materials are essential for experimental validation of Monte Carlo simulations in a biomedical context.

Table 4: Essential Materials for Experimental Validation

| Material / Solution | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Tissue-Substitute Phantoms (e.g., ballistic gel, HDPE) | Mimics the radiation interaction properties of human tissue for controlled, reproducible benchmark measurements [9] [22]. |

| Cerium Bromide (CeBr₃) Scintillator | A radiation detector with good energy resolution, used for spectroscopy of prompt gamma rays [20]. |

| Sodium Iodide (NaI(Tl)) Scintillation Detector | A widely used detector for measuring gamma-ray flux and energy spectra in attenuation experiments [21] [22]. |

| Radioactive Sources (e.g., ¹³⁷Cs, ²²⁶Ra) | Provide known and stable gamma-ray emissions (e.g., 662 keV from ¹³⁷Cs) for calibrating detectors and validating simulations [21] [22]. |

| Bismuth Germanate (BGO) Detector Modules | Used in the detector blocks of positron emission tomography (PET) systems for in-beam range verification [9]. |

| Validated Cross-Section Libraries (e.g., NDS, EXFOR) | External datasets for nuclear reaction probabilities, often providing higher accuracy than default theoretical models in MC codes [9]. |

Workflow Diagram for Code Validation

The diagram below outlines the standard workflow for validating a Monte Carlo model against experimental data, a process critical for ensuring simulation reliability.

Model Validation Workflow

The comparative data indicates that no single Monte Carlo code is universally superior; performance is highly dependent on the specific application.

- GEANT4 and GATE demonstrate strong performance in medical physics, particularly for complex problems like prompt gamma simulation and PET verification. Their open-source nature and active development allow for continuous improvement and integration of more accurate physics models and cross-section data [20] [9] [18].

- MCNP6 remains a robust and reliable code for traditional applications such as photon shielding, showing excellent agreement with experimental attenuation measurements [21].

- PHITS is a capable tool for photon transport and heavy ion applications, though its performance in predicting certain nuclear fragmentation products (e.g., β+ emitters) may require further model development to match the accuracy of GEANT4 in some therapeutic scenarios [22] [23].

- Model Selection is Critical: The significant difference in results observed when using different physics models (e.g., QGSP_BIC vs. NDS cross-sections in GATE) underscores that the user's choice of physics settings is as important as the choice of the code itself [9]. Validation against experimental data is the only way to build confidence in a particular simulation setup.

For researchers validating models with experimental tissue data, the key is to select a code whose strengths align with the project's physical processes and to employ a rigorous, iterative validation workflow using well-characterized phantoms and detectors.

The fidelity of computational models to experimental reality forms the bedrock of scientific reliability in fields ranging from radiation therapy to drug development. Validation metrics serve as the crucial, quantitative bridge between simulation and experiment, providing the objective evidence needed to trust model predictions in critical applications. This guide systematically compares the performance of various validation approaches and metrics, with a particular focus on Monte Carlo (MC) simulation frameworks validated against experimental tissue data.

As computational models grow more complex, moving beyond simple point-to-point comparisons to multi-dimensional validation has become essential. Different applications demand specialized metrics sensitive to specific types of discrepancies, whether assessing radiation dose distributions for cancer treatment, verifying proton beam ranges in therapy, or quantifying drug responses in pharmaceutical screening. This comparative analysis examines the experimental protocols, performance characteristics, and appropriate applications of leading validation methodologies, providing researchers with the data needed to select optimal validation strategies for their specific domain.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Metrics and Methods

The table below summarizes key validation metrics across different domains, highlighting their applications, acceptance criteria, and performance characteristics based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Validation Metrics and Methods

| Application Domain | Primary Metric(s) | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Performance & Limitations | Experimental Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOERT/IMRT/VMAT Dose Validation | Gamma analysis (dose difference + DTA) [24] [25] | 2%/1 mm to 3%/3 mm; >90-95% passing rate [24] [25] | 3%/3 mm may miss clinically relevant errors; 2%/1 mm more sensitive [25] | Water phantom measurements; diode/ion chamber arrays [24] [26] |

| Proton Range Verification | Activity range deviation; Distal fall-off alignment [9] | Mean range deviation <1 mm ideal; 2-4 mm may require model adjustment [9] | Highly dependent on nuclear cross-section data; NDS/EXFOR models show best accuracy [9] | Dual-head PET system; β+ emitter detection [9] |

| Radiation Shielding Evaluation | Linear/Mass Attenuation Coefficient; HVL/TVL [27] | Discrepancy <5% between simulation and experiment [27] | MCNP6 and GEANT4 show good agreement (<5%) with experimental measurements [27] | Cs-137 source (662 keV); PMMA-HgO composites [27] |

| Drug Response Quantification | Normalized Drug Response (NDR) [28] | Improved consistency (p<0.005) vs. PI and GR metrics [28] | Accounts for background noise and growth rates; wider spectrum of drug effects [28] | Cell viability assays (luminescence) [28] |

| 3D Dose Volume Validation | Dose-Volume Histogram (DVH) metrics [26] | PTV D95 difference <2% in error-free plans [26] | Sensitivity varies with plan complexity; may miss errors in simple plans [26] | ArcCHECK measurements with 3DVH software [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Monte Carlo Model Validation for Radiation Therapy Systems

Recent research on IOERT accelerator validation exemplifies rigorous MC model testing. The LIAC HWL mobile accelerator model was implemented using PENELOPE/penEasy code with a hypothetical head geometry due to manufacturer disclosure limitations. The validation protocol involved comparing simulated and measured Output Factors (OFs), Percentage Depth Doses (PDDs), and Off-Axis Ratios (OARs) in a virtual water phantom for various applicator sizes (3-10 cm diameter), bevel angles (0°-45°), and energies (6, 8, 10, 12 MeV). Gamma analysis criteria of 2% dose difference and 1 mm distance-to-agreement were applied, with results showing >93% passing rates in most cases. The worst performance occurred with the smallest applicator (3 cm diameter) with 45° bevel angle at 6 MeV, where passing rates dropped to 85.7-86.1% [24].

Proton Range Verification via PET Detection

A comprehensive validation study for proton range verification utilized a dual-head PET (DHPET) system mounted on a rotating gantry in the treatment room. Researchers compared three nuclear models: the built-in GEANT4 QGSPBIC model, EXFOR-based cross-sections, and the updated NDS dataset. The experimental protocol involved irradiating high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and gel-water phantoms with monoenergetic proton beams (70-210 MeV), followed by PET imaging to detect positron-emitting isotopes (¹¹C, ¹⁵O) generated during irradiation. The distal fall-off of the activity distribution was compared to the dose fall-off from treatment planning system calculations. Results showed that NDS and EXFOR models achieved mean range deviations within 1 mm in HDPE phantoms, while QGSPBIC underestimated the distal range by 2-4 mm [9].

Advanced Validation Beyond Conventional Gamma Analysis

Studies have revealed limitations in conventional gamma analysis for IMRT/VMAT commissioning. When applying the typical 3%/3 mm criteria with global normalization, passing rates often exceeded 99% for per-beam analysis and 93.9-100% for composite plans - well above TG-119 action levels of 90% and 88%, respectively. However, more sensitive analysis using 2%/2 mm local normalization and advanced diagnostics like EPID-based measurements and dose profile examination uncovered systematic errors that caused target dose coverage loss up to 5.5% and local dose deviations up to 31.5%. These errors included TPS model limitations, algorithm inaccuracies, and QA phantom modeling issues [25].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Experiments

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Examples | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ArcCHECK with 3DVH Software | 3D dose measurement & reconstruction in patient geometry [26] | VMAT plan validation; DVH metric estimation [26] | Uses Planned Dose Perturbation (PDP) algorithm; requires complementary ion chamber measurement [26] |

| PENELOPE/penEasy MC Code | Electron and photon transport simulation [24] | IOERT accelerator modeling; dose distribution calculation [24] | Provides PSFs in IAEA format; supports hypothetical geometries when exact specs unavailable [24] |

| GATE Simulation Platform | GEANT4-based MC simulation for medical applications [9] | Proton therapy range verification; PET detector simulation [9] | Simulates entire chain from beam delivery to image reconstruction [9] |

| MCNP6 & GEANT4 Codes | General-purpose radiation transport simulation [27] | Shielding material evaluation; attenuation coefficient calculation [27] | MCNP6 highly accurate with established nuclear data; GEANT4 offers flexibility [27] |

| PMMA-HgO Composites | Novel shielding material for experimental validation [27] | Gamma shielding performance; composite material modeling [27] | HgO filler increases linear attenuation from 0.044 cm⁻¹ (pure PMMA) to 0.096 cm⁻¹ [27] |

| RealTime-Glo Assay | Cell viability measurement for drug screening [28] | NDR metric calculation; high-throughput drug profiling [28] | Luminescence-based; requires positive and negative controls for normalization [28] |

Visualizing Validation Workflows

Diagram 1: Model Validation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for validating computational models against experimental data, highlighting the parallel paths of experimental measurement and simulation development that converge at the metric comparison stage.

Diagram 2: Validation Metric Taxonomy. This diagram categorizes the primary validation metrics used across different applications, showing how they specialize for particular validation scenarios while sharing the common goal of quantifying agreement between simulation and experiment.

Effective validation requires carefully selected metrics that are sensitive to the specific types of errors most likely to occur in a given application. While gamma analysis with 2%/1-2 mm criteria provides robust validation for photon and electron dose distributions, proton range verification demands specialized PET-based activity distribution comparison with attention to nuclear cross-section data. For 3D dose validation, DVH-based metrics offer clinical relevance but require understanding of their sensitivity limitations in different plan complexities.

The most successful validation approaches combine multiple complementary metrics rather than relying on a single test. As computational models continue to evolve toward more complex biological systems and real-time applications, validation methodologies must similarly advance with tighter tolerances, more diligent diagnostics, and multidimensional assessment strategies. The experimental data and comparative analysis presented here provide researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting validation approaches that will ensure model reliability across medical physics and pharmaceutical development applications.

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Therapy and Imaging

Calibrating In-Vivo Monitoring Systems and Internal Dosimetry Phantoms

The validation of computational models with robust experimental data is a cornerstone of reliable internal dosimetry and in vivo monitoring. Within this framework, physical phantoms that mimic human anatomy and optical properties are indispensable for benchmarking and refining Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, which are a primary tool for modeling complex radiation and light transport phenomena [29] [30]. This guide objectively compares different calibration methodologies and phantom-based validation approaches, providing a structured overview of their performance, experimental protocols, and key applications. The focus is on providing researchers with comparative data to select appropriate techniques for validating their MC models, ultimately enhancing the accuracy of in vivo dose and physiological measurements.

Comparative Analysis of Phantom-Based Validation Methodologies

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, performance data, and applications of several phantom-based validation approaches identified in the literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Phantom-Based Validation Methodologies for Monte Carlo Models

| Methodology / System | Key Performance Metrics / Outcomes | Reported Limitations / Challenges | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Phantom + MC Model for Ocular Oximetry [29] | Assessed impact of confounding factors (scattering, blood volume); quantified choroidal circulation effect on accuracy. | Complex layered structure of eye fundus difficult to replicate with phantoms; no gold-standard for validation. | Validation of diffuse reflectance-based ocular oximetry techniques. |

| EURADOS MC Intercomparison (Skull Phantoms) [30] | Good agreement between simulated and measured spectra for task 2A/2B; ~33% of participants needed simulation revisions. | Human error in simulations (e.g., inaccurate detector modeling, scoring errors); some physical phantoms not representative. | Calibration of germanium detector systems for in vivo monitoring of Am-241 in the skull. |

| Monte Carlo-Based Inverse Model for Tissue Optics [31] | Extracted optical properties with average error of ≤3% (hemoglobin phantoms) and ≤12% (Nigrosin phantoms). | Performance varies with absorber type (higher error for Nigrosin). | Extraction of absorption and scattering properties of turbid media from diffuse reflectance. |

| Noncontact Depth-Sensitive Fluorescence Validation [32] | Experimentally verified MC model of cone/cone-shell illumination; model provides fast, inexpensive optimization platform. | Experimental optimization of parameters (e.g., axicon lenses) is time-consuming and costly. | Optimization of noncontact, depth-sensitive fluorescence probes for epithelial tissue diagnostics. |

| EPID In Vivo Monitoring System (SunCHECK PerFRACTION) [33] | Dose calculation deviations <1.0% in water-equivalent regions; detected output variations within 1.2%; agreed with TLD audit within 2-3.7%. | Higher deviations (~7.3%) in highly heterogeneous (e.g., lung) regions, though results were expected. | In vivo dose verification for radiotherapy using Electronic Portal Imaging Device (EPID). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section elaborates on the experimental methodologies that generated the data in the comparison table.

Two-Step Phantom and MC Validation for Ocular Oximetry

This protocol uses a hybrid approach to validate an ocular oximetry technique, isolating the effects of specific confounding factors [29].

- Tissue Phantom Construction: Phantoms are designed to investigate specific variables, such as scattering properties, blood volume fraction (BVF), and the spectral transmission of the crystalline lens.

- Phantom Measurement: The diffuse reflectance spectrum of the phantom is acquired using the oximetry device. The raw signal is processed to isolate the reflectance from the phantom itself by accounting for device-specific optical reflections and ambient radiation [29].

- Multi-Wavelength Oxygen Saturation Algorithm: The optical density (OD) spectrum is calculated. A modified Beer-Lambert law model is fitted to the OD spectrum to determine the concentrations of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin, incorporating empirical terms for scattering, melanin, and the crystalline lens [29]. The oxygen saturation is calculated as the ratio of oxygenated hemoglobin to total hemoglobin.

- Monte Carlo Simulation of Layered Structure: A separate MC model of the light propagation in the multi-layered eye fundus is developed. This model is used to study the effect of the fundus layered-structure, which is difficult to replicate with physical phantoms, and to quantify the impact of factors like choroidal blood oxygen saturation.

International MC Intercomparison Exercise for Skull Phantoms

This protocol, organized by EURADOS, outlines a standardized method for validating MC codes used in in vivo monitoring of radionuclides [30].

- Phantom Selection: Multiple anthropomorphic head phantoms are used, including a voxelized version of a real human skull (BfS phantom) with known 241Am activity and a physical CSR phantom.

- Reference Measurements: Participants are provided with measurement data from these phantoms using defined germanium detectors.

- Computational Tasks:

- Task 1: Participants simulate a predefined detector and phantom setup using their MC codes to check their ability to reproduce reference results.

- Task 2: Participants build a model of their own real detector and compare its simulated response with actual measurements from the BfS and CSR phantoms.

- Task 3: Participants simulate the entire geometry of a typical in vivo measurement as performed in their laboratory.

- Result Comparison and Analysis: The organizers compare the detection efficiencies and spectra reported by all participants against the master reference measurements to identify discrepancies and common sources of error.

Validation of an EPID-Based In Vivo Dosimetry System

This protocol evaluates the performance of a commercial software for in vivo dose monitoring during radiotherapy [33].

- Error Detection Capability:

- Output Variation: LINAC output is intentionally altered, and the system's calculated dose on the EPID plane is compared to ionization chamber measurements.

- Phantom Thickness Variation: The thickness of a homogeneous phantom is reduced by 2 cm during irradiation. The system's calculated 3D dose in a CBCT scan is compared to ionization chamber measurements.

- Independent Audit Comparison: Four different phantoms are irradiated based on an external audit program's instructions. The dose deviations reported by the software based on EPID measurements are compared against the deviations reported by the audit using TLDs.

- End-to-End Test with Heterogeneous Phantom: A volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) plan is delivered to a heterogeneous phantom. The software calculates the 3D dose on a CBCT using log files and EPID-measured MLC positions. The calculated dose at specific points is compared to ionization chamber measurements placed within the phantom.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows for key validation methodologies described in this guide.

Ocular Oximetry Validation Workflow

MC Model & Phantom Validation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials and their functions as derived from the experimental protocols cited in this guide.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Phantom-Based Validation

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experimental Context | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical Phantoms | Physical models with known geometry and composition used as a substitute for human tissue to provide a ground truth for measurements and simulations. | BfS skull phantom (donor skull with known 241Am activity); two-layered tissue phantoms mimicking skin/eye fundus [30] [32]. |

| Hemoglobin Derivatives | Act as absorbers in liquid phantoms to simulate the spectral properties of blood for oximetry calibration. | Used in liquid phantoms with polystyrene spheres as scatterers to validate a Monte Carlo-based inverse model [31]. |

| Polystyrene Spheres | Common scattering agents in liquid phantoms used to simulate the light scattering properties of biological tissues. | Employed in tissue phantoms to provide a controlled reduced scattering coefficient [31]. |

| Electronic Portal Imaging Device (EPID) | A detector mounted on a linear accelerator used for transmission dosimetry and in vivo verification of radiation dose during radiotherapy. | Central component of the SunCHECK PerFRACTION system for performing 2D and 3D dose calculations during treatment [33]. |

| Germanium Detector | High-resolution radiation detector for measuring low-energy photons, essential for quantifying radionuclides like Am-241. | Used by participants in the EURADOS intercomparison for measuring spectra from skull phantoms [30]. |

| Ionization Chamber | A reference-grade instrument for absolute dose measurement in radiology, used to benchmark other dosimetry systems. | Used as a reference to measure introduced dose variations in EPID system tests [33]. |

| Axicon Lenses | Optical components that create a ring-shaped "cone shell" illumination, used to enhance depth sensitivity in non-contact optical measurements. | Implemented in a non-contact probe to achieve depth-sensitive fluorescence measurements from layered phantoms [32]. |

Proton Therapy Range Verification Using In-Beam PET and Monte Carlo Simulations

The superior dose conformity of proton therapy, characterized by the Bragg peak, allows for highly localized energy deposition within a tumor target. However, this advantage is counterbalanced by sensitivity to range uncertainties, which can lead to under-dosage of the tumor or overexposure of adjacent healthy tissues [34] [35]. In-vivo range verification is therefore critical for ensuring treatment quality. This guide compares two prominent techniques for non-invasive range verification: Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Prompt Gamma Imaging (PGI), with a specific focus on the integral role of Monte Carlo (MC) simulations in developing and validating these methods. The content is framed within the broader thesis that rigorous validation of MC models against experimental tissue data is a prerequisite for their reliable application in clinical range verification.

Comparative Analysis of Range Verification Methods

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, performance data, and technological requirements of the two primary range verification methods discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Range Verification Methods in Proton Therapy

| Feature | In-Beam PET | Prompt Gamma Imaging (PGI) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Detection of annihilation photons (511 keV) from (\beta^+) emitters (e.g., (^{11})C, (^{15})O, (^{13})N, (^{18})F) produced by nuclear fragmentation [34] [36]. | Detection of high-energy photons emitted instantaneously during nuclear de-excitation [37] [34]. |

| Temporal Relationship | Integration occurs post-irradiation (seconds to minutes); activity represents a cumulative history of the beam path [34] [38]. | Direct, real-time monitoring during beam delivery [37]. |

| Key Performance Metrics | - F-18 PET matches planned dose fall-off within 1 mm [36].- Activity-range can be measured within 1.0 mm within few beam spills [38]. | - >90% accuracy in identifying range shifts ≥2 mm with (10^8) protons [37].- Area under ROC curve of 0.9 for a +1 mm shift at (1.6\cdot10^8) protons [37]. |

| Advantages | - Can utilize both in-beam and offline imaging [38].- Well-established imaging technology and reconstruction algorithms.- F-18 offers superior correlation with dose due to low positron energy [36]. | - True real-time feedback potential.- Higher signal yield compared to positron emitters.- No radioactive decay wait time. |

| Disadvantages/Challenges | - Biological washout of emitters can blur the activity distribution [34].- Low activity concentrations (Bq/ml range) post-irradiation require sensitive detectors [36]. | - Complex detector design and shielding requirements.- Requires sophisticated spectroscopy and timing electronics.- The emitted spectrum is a linear sum of elemental constituents, requiring spectral unfolding [37]. |

| MC Simulation Codes Used | GATE, MCNPX [38] | Geant4 [37] |

| Primary Clinical Role | Dose verification and post-facto range assessment, enabling adaptive therapy [36] [38]. | Real-time beam range monitoring and control [37]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Range Verification Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| GAMOS | A Monte Carlo code based on Geant4, validated for brachytherapy and capable of simulating dose deposition in various tissues, including bone and brain [39]. |

| Geant4 | A versatile Monte Carlo platform widely used in particle therapy to simulate particle transport and nuclear interactions for detector design and signal prediction [37] [34]. |

| GATE | A specialized Monte Carlo toolkit based on Geant4, designed for PET and SPECT simulations. It is used to simulate scanner performance and image formation [38]. |

| PHITS | A general-purpose Monte Carlo code for transporting various particle types; used for modeling radiation interactions and calculating parameters like linear attenuation coefficients in tissue substitutes [40]. |

| PENELOPE | A Monte Carlo code integrated with the penEasy framework, used for modeling linear accelerators and validating dose distributions in complex geometries [24]. |

| NOVCoDA (NOVO Compact Detector Array) | A compact detector array using bar-shaped organic scintillators and silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs) for simultaneous imaging of prompt gamma rays and fast neutrons [37]. |

| Ballistic Gel (BGel) | A tissue-equivalent material used to fabricate physical phantoms for experimental calibration of radiation detectors and validation of MC simulations [40]. |

| Solid Water | A commercially available tissue-substitute phantom material used for detector calibration and dosimetric measurements. MC simulations provide conversion factors to translate dose from Solid Water to actual human tissues [39]. |

| LYSO and BGO Crystals | Scintillator materials used in PET detectors. LYSO offers fast timing and high efficiency, while BGO is common in clinical scanners. Their performance is evaluated for detecting low activity concentrations in proton therapy [36]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol: In-Beam PET for Intra-Treatment Adaptive Proton Therapy

This protocol, based on the work by Lou et al. [38], outlines the methodology for rapid beam-range verification using MC simulations and PET imaging.

Phantom and Beam Irradiation Simulation:

- Tool: MCNPX Monte Carlo package.

- Action: Simulate the irradiation of a uniform cylindrical PMMA phantom with a collimated 180 MeV pristine proton beam.

- Output: A high-fidelity spatial distribution of positron emitters ((^{11})C, (^{15})O, (^{13})N) generated within the phantom.

PET System and Data Acquisition Simulation:

- Tool: GATE Monte Carlo toolkit.

- Action: Simulate two PET geometries—a dual-panel rotational PET and a stationary brain PET with Depth-of-Interaction (DOI) capability—to model the detection of coincidence events from the generated activity.

- Parameters: Vary the number of beam spills, total acquisition time (during- and post-irradiation), crystal cross-section size, and crystal length.

Image Reconstruction and Data Analysis:

- Tool: List-mode Maximum-Likelihood Expectation-Maximization (MLEM) algorithm.

- Action: Reconstruct images from the simulated coincidence data.

- Measurement: Quantify the "positron activity-range" from the reconstructed images as a function of the accumulated statistics (number of coincidence events). The convergence of this measured range towards its final value is tracked as data statistics increase.

Protocol: Prompt Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy with NOVCoDA

This protocol summarizes the methodology for using prompt gamma-ray spectra to detect proton beam range shifts [37].

Monte Carlo Simulation and Spectral Library Creation:

- Tool: Geant4.

- Action: Perform MC simulations to generate a library of elemental prompt gamma-ray spectra for various constituent elements in the target.

- Assumption: The total measured prompt gamma-ray spectrum is modeled as a linear sum of these individual elemental spectra (Monte Carlo Library Least Squares Approach).

Range Shift Classification:

- Action: Simulate various proton beam range shifts in a target.

- Tool: Apply a Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA) classifier to the simulated prompt gamma-ray spectra.

- Output: The classifier identifies and quantifies the magnitude of any present range shifts (e.g., +1 mm, -1 mm, ±2 mm).

Performance Evaluation:

- Metrics: Determine the accuracy of range shift classification and calculate the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve.

- Parameters: Evaluate these metrics as a function of incident proton intensity (number of protons) to establish the minimum required statistics for reliable detection.

Workflow and System Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows for range verification and Monte Carlo model validation.

In-Beam PET Verification Workflow

Monte Carlo Model Validation Logic

In-beam PET and prompt gamma imaging offer complementary pathways toward solving the critical challenge of range verification in proton therapy. PET provides a direct method for dose verification with high spatial accuracy, as evidenced by its ability to correlate F-18 activity with dose fall-off within 1 mm [36]. Prompt gamma imaging, with its real-time capability and high classification accuracy for range shifts greater than 2 mm, is a powerful tool for live monitoring [37]. The effective development and clinical translation of both technologies are fundamentally reliant on high-fidelity Monte Carlo simulations. As the field progresses, the continued validation of these MC models against experimental data from tissue substitutes and clinical phantoms remains the cornerstone for building the confidence required to reduce safety margins and fully exploit the physical advantages of proton therapy.

Deep Learning for Rapid Monte Carlo Dose Prediction in Heavy Ion Therapy

In heavy ion therapy (HIT), the precision of dose calculation is paramount for maximizing tumor control while sparing surrounding healthy tissues. The Monte Carlo (MC) method is considered the gold standard for dose calculation due to its accurate modeling of complex particle transport physics. However, its extensive computational requirements, often taking hours or even days to complete a single simulation, have historically limited its routine clinical application [5] [41]. To address this critical bottleneck, deep learning (DL) has emerged as a powerful tool for predicting MC-simulated dose distributions (MCDose) in seconds rather than hours. These DL models learn the complex mapping from patient inputs, such as computed tomography (CT) images, to high-fidelity 3D dose distributions, achieving accuracy comparable to full MC simulations while offering the speed necessary for online adaptive radiotherapy and rapid quality assurance [42]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of current deep learning architectures for rapid MCDose prediction, detailing their experimental protocols, performance data, and the essential research tools required for their development and validation.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Deep Learning Model Architectures

Several specialized convolutional neural network architectures have been proposed for MCDose prediction in HIT.

CHD U-Net (Cascade Hierarchically Densely Connected U-Net): This model features a two-stage, cascaded 3D U-Net architecture that incorporates dense connections. The first stage network takes CT images and the treatment planning system analytical dose (TPSDose) as inputs to generate an initial MCDose prediction. The second-stage network then refines this prediction using the first stage's input and output. Key components include dense convolution modules, dense downsampling modules, and skip connections that combine downsampled and upsampled feature maps. This design improves gradient flow and feature propagation, enabling more accurate dose prediction, particularly in critical regions like the Planning Target Volume (PTV) [5] [41].

CAM-CHD U-Net: An enhancement of the CHD U-Net, this model integrates a Channel Attention Mechanism (CAM) into the original architecture. The CAM allows the network to adaptively weight the importance of different feature channels, focusing computational resources on the most informative features for dose prediction. This has been shown to improve performance in complex anatomical regions [42].

Comparative Models (C3D and HD U-Net): These are baseline architectures used for performance comparison. The C3D is a simpler 3D convolutional network, while the HD U-Net is a hierarchically dense U-Net without the cascade structure of the CHD U-Net [5] [41].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The development and validation of these models typically involve the following standardized protocol.

- Patient Data: Models are trained and tested on retrospective clinical data, including CT images, structure sets (delineating organs at risk and target volumes), and corresponding TPSDose distributions. Cohort sizes are often in the range of 67 head-and-neck patients and 30 thorax-and-abdomen patients [41].

- Ground Truth MCDose: The reference MCDose is calculated using full Monte Carlo simulation platforms like GATE/Geant4. Simulations use the same beam parameters (spot positions, energies, weights) as the clinical treatment plan and track a high number of particles (e.g., 10^8) to ensure statistical noise is kept below 1% [41] [9].

- Data Preprocessing: Input data (CT and TPSDose) are converted into 3D matrices. CT Hounsfield Units (HU) are typically cropped and normalized to a [0, 1] range. Dose values are also normalized. To optimize GPU memory usage, data is often downsampled (e.g., to 256x256x64 resolution). Online data augmentation techniques, including random flipping, rotation, and panning, are applied during training to improve model generalization [41].

Model Training and Evaluation

- Training Configuration: Models are implemented in frameworks like PyTorch and trained on high-performance GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A6000). The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) between the predicted dose and the ground truth MCDose is commonly used as the loss function. Optimization is performed with the Adam optimizer, often incorporating techniques like deep supervision to improve learning in intermediate layers [41].

- Performance Metrics: The primary metric for evaluation is the Gamma Passing Rate (GPR), which provides a composite measure of dose difference and distance-to-agreement. Standard criteria used include 3%/3mm (clinically relevant) and more stringent 1%/1mm. Evaluation is performed separately for the PTV region and the entire body to ensure accuracy in both the target and overall dose distribution [5] [41] [42].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Deep Learning-based MCDose Prediction. This illustrates the two-stage cascade architecture of the CHD U-Net model and its validation process.

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize the key performance metrics of different deep learning models for MCDose prediction, enabling an objective comparison.

Table 1: Gamma Passing Rate (GPR) performance comparison of different deep learning models for head-and-neck and thorax-abdomen patients. Performance is shown for both the Planned Target Volume (PTV) and the entire body under the 3%/3mm criterion.

| Anatomical Region | Model | GPR in PTV (%) | GPR in Body (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head-and-Neck | CHD U-Net | 97 | 98 |

| C3D | 97 | 98 | |

| HD U-Net | 85 | 97 | |

| Thorax-Abdomen | CHD U-Net | 71 | 95 |

| C3D | 71 | 95 | |

| HD U-Net | 51 | 90 | |

| Table 1 Source: [5] [41] |

Table 2: Performance of the advanced CAM-CHD U-Net model for head-and-neck cancer patients, demonstrating improved accuracy over the base CHD U-Net.

| Metric | CAM-CHD U-Net Performance |

|---|---|

| GPR in PTV (3%/3mm) | 99.31% |

| GPR in Body (3%/3mm) | 96.48% |

| Reduction in Mean Absolute Difference (D5) | 46.15% |

| Calculation Time | A few seconds |

| Table 2 Source: [42] |

Table 3: Comparison of computational performance between traditional Monte Carlo simulation and the deep learning-based prediction approach.

| Method | Calculation Time | Hardware Requirements | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full MC Simulation (GATE/Geant4) | Several minutes to hours | Two Intel Xeon Gold 6148 CPUs (80 parallel calculations) | Gold standard accuracy |

| DL Prediction (CHD U-Net) | A few seconds | Single NVIDIA A6000 GPU | Clinical feasibility & speed |

| Table 3 Source: [5] [41] |

Critical Analysis of Performance Data

The data reveals several key insights:

- Superior Performance of Advanced Architectures: The CHD U-Net consistently outperforms the simpler HD U-Net, particularly in the challenging thorax-abdomen region where anatomical heterogeneity is high. The 20% higher GPR in the PTV for this region underscores the importance of the cascade and dense connection architecture [5] [41].

- High Clinical Readiness: All advanced models (C3D, CHD U-Net, CAM-CHD U-Net) achieve GPRs exceeding 95% in the body for head-and-neck cases under the clinical 3%/3mm criterion. This indicates that the overall dose distribution is predicted with high accuracy. The CAM-CHD U-Net's >99% GPR in the PTV highlights a significant step towards clinical adoption [42].

- Anatomical Dependency: Performance is generally higher for head-and-neck patients compared to thorax-abdomen patients. This is likely due to greater tissue heterogeneity and organ motion in the thorax and abdomen, presenting a more complex prediction challenge [41].

This section catalogs the critical software, data, and hardware components required for developing and validating deep learning models for MCDose prediction.

Table 4: Key research reagents and solutions for deep learning-based Monte Carlo dose prediction.

| Tool Category | Specific Tool / Resource | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo Simulation Platform | GATE/Geant4 [41] [9] | Generates the ground truth MCDose for training and testing DL models; simulates particle transport and interactions. |

| Treatment Planning System (TPS) | matRad [41], RayStation [9] | Provides the analytical dose algorithm calculation (TPSDose) used as an input to the DL models. |

| Deep Learning Framework | PyTorch [41] | Provides the programming environment for building, training, and testing the 3D U-Net architectures. |

| Medical Imaging Data | Patient CT Images & Structure Sets [41] | Serves as the primary anatomical input for the DL model to learn the relationship between tissue density and dose deposition. |

| High-Performance Computing | NVIDIA GPU (e.g., A6000) [41] | Accelerates the training of large 3D convolutional networks, reducing computation time from days to hours. |

| Validation Metric | Gamma Passing Rate (GPR) [5] [41] [42] | The standard metric for quantitatively comparing predicted and ground truth dose distributions in clinical radiotherapy. |

Deep learning models, particularly advanced architectures like the CHD U-Net and CAM-CHD U-Net, have demonstrated remarkable feasibility for predicting Monte Carlo dose distributions in heavy ion therapy with high accuracy and sub-minute computational speeds. The experimental data confirms that these models can achieve gamma passing rates above 97% in many clinical scenarios, making them suitable for integration into clinical workflows for tasks such as online adaptive radiotherapy and rapid, independent quality assurance [5] [42]. The primary advantage lies in decoupling the accuracy of the Monte Carlo method from its prohibitive computational cost.

Future research in this field is directed towards several key areas:

- Improving Robustness in Heterogeneous Anatomies: Enhancing model performance in thorax and abdomen sites through more sophisticated architectures and training strategies remains a priority [41].

- Clinical Integration for Online Adaptation: The near-instantaneous prediction capability opens the door for real-time re-planning in online adaptive radiotherapy (OART), which is crucial for accounting for inter-fractional anatomical changes [42].

- Expansion to Other Modalities: While this guide focuses on heavy ion therapy, the underlying principles are being actively applied to proton therapy and other external beam radiotherapy modalities, promising widespread impact on radiation oncology [43].

GPU-Accelerated Monte Carlo for Real-Time Dosimetry in Interventional Radiology

In interventional radiology, the real-time estimation of patient radiation dose is a significant challenge. Conventional dosimetry methods, including thermoluminescent dosimeters (TLDs), struggle to provide comprehensive dose distribution data across extended organs like the skin, offering information only for specific points and with a time delay [44]. Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, which meticulously model the stochastic nature of particle transport, are considered the gold standard for radiation dose computation [4] [45] [46]. However, their widespread clinical adoption in interventional radiology has been hampered by extremely long computation times, often taking hours or days on central processing units (CPUs) [47] [44].

The emergence of graphics processing unit (GPU)-accelerated Monte Carlo codes has presented a paradigm shift, offering the potential for real-time or near-real-time dose assessment. By leveraging the massive parallel processing power of GPUs, these platforms can achieve speedups exceeding 100 to 1,000 times compared to traditional CPU-based MC codes [4]. This review objectively compares the performance of several GPU-accelerated MC platforms, validating their accuracy against established codes and experimental data, and examines their integration into the clinical workflow for interventional radiology.

Comparative Analysis of GPU-Accelerated Monte Carlo Platforms

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of several GPU-accelerated Monte Carlo codes as validated in recent scientific literature.