Polymer vs. Silica Fiber Bragg Gratings for Biomedical Sensing: A Comprehensive Comparison for Researchers

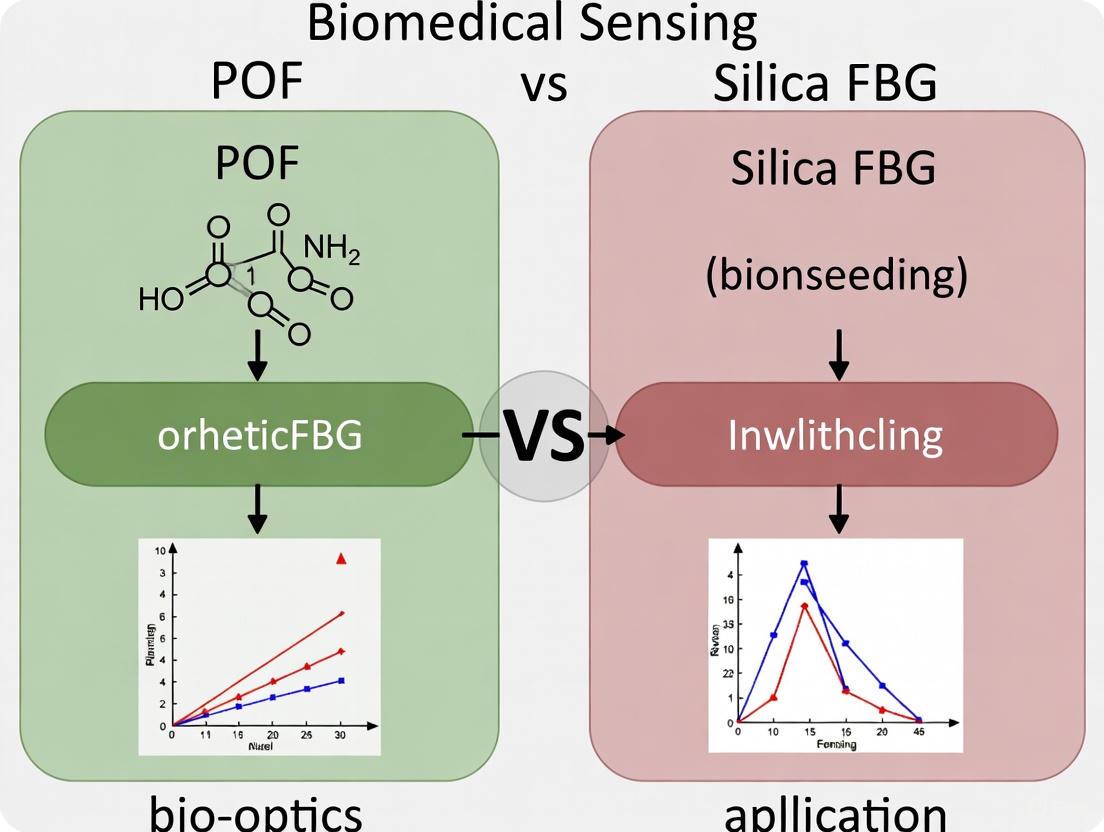

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) and silica-based Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors for biomedical applications.

Polymer vs. Silica Fiber Bragg Gratings for Biomedical Sensing: A Comprehensive Comparison for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) and silica-based Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors for biomedical applications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles, material properties, and distinct advantages of each technology. The scope encompasses a methodological review of current applications in physiological monitoring and biochemical sensing, an analysis of critical challenges including biocompatibility and signal processing, and a direct performance validation comparing sensitivity, mechanical properties, and cost-effectiveness. The goal is to offer a foundational guide for selecting and optimizing fiber optic sensor technology to advance biomedical diagnostics and monitoring.

Fundamental Principles and Material Properties of POF and Silica FBGs

Basic Operating Principle of Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs) and Light-Matter Interaction

A Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) is a periodic modulation of the refractive index within the core of an optical fiber, effectively creating a wavelength-specific dielectric mirror [1]. This fundamental component of fiber-optic technology was first demonstrated by Ken Hill in 1978, with a more flexible transverse holographic inscription technique developed by Gerald Meltz and colleagues in 1989 [1]. FBGs have revolutionized sensing capabilities across numerous fields, including telecommunications, structural health monitoring, and biomedical engineering, due to their compact size, high sensitivity, and immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI) [2] [3]. The core principle of an FBG is its ability to reflect a very specific wavelength of light—the Bragg wavelength—while transmitting all others, a characteristic that forms the basis for its sensing mechanism [4] [1]. When external parameters such as strain or temperature change, they alter the grating's period or the fiber's refractive index, causing a measurable shift in the Bragg wavelength [3]. This review will explore the basic operating principle of FBGs and the critical light-matter interactions that underpin their function, with a specific focus on comparing their implementation in traditional silica fibers versus emerging Polymer Optical Fibers (POFs) for biomedical sensing applications.

Fundamental Working Principle of FBGs

The Bragg Condition and Light Interaction

The operation of a Fiber Bragg Grating is governed by the Bragg Condition, a physical law that dictates the specific wavelength at which the grating will reflect light. An FBG is fabricated by laterally exposing the core of a single-mode optical fiber to a periodic pattern of intense ultraviolet laser light [4] [1]. This exposure creates a permanent, periodic increase in the refractive index of the fiber's core, forming a structure known as a grating [4].

As light propagates through the optical fiber, it encounters this periodic grating. At each point of refractive index change, a small amount of light is reflected. When the grating period (Λ) is approximately half the incident light's wavelength (λ) in the material, all these small reflections from each period combine coherently to form one large, collective reflection [4]. This condition is described by the Bragg equation:

λBragg = 2neffΛ

Here, λBragg is the Bragg wavelength, neff is the effective refractive index of the fiber core, and Λ is the grating period (the spacing between the index modulations) [4] [1]. Light at wavelengths other than the Bragg wavelength passes through the grating with negligible attenuation or signal variation [4]. The following diagram illustrates this fundamental principle of operation and the subsequent sensing mechanism.

FBG Sensing Mechanism

The FBG's functionality as a sensor arises from the direct influence of environmental conditions on the parameters in the Bragg equation. When an FBG is subjected to strain, the physical elongation or compression of the fiber alters the grating period (Λ). Simultaneously, the strain-optic effect causes a change in the effective refractive index (neff) [5]. Similarly, changes in temperature affect the fiber through thermal expansion or contraction (altering Λ) and the thermo-optic effect (altering neff) [5]. These combined effects result in a shift of the Bragg wavelength (ΔλB), which is directly measurable and quantifiable.

The strain and temperature dependence can be expressed as follows [5]:

Strain Dependence: ΔλB / λB = (1 + pe) * Δε Where

peis the strain-optic coefficient andΔεis the applied strain.Temperature Dependence: ΔλB / λB = (α + ζ) * ΔT Where

αis the thermal expansion coefficient andζis the thermo-optic coefficient.

This wavelength-encoded nature of FBG sensors is a key advantage, making the measurement independent of the light source intensity or losses in the optical path [2]. Furthermore, multiple FBGs, each with a different Bragg wavelength, can be inscribed into a single optical fiber, enabling multiplexing and distributed multi-point sensing, which is particularly valuable for monitoring large structures or complex biological systems [2] [3].

Key Materials: Silica vs. Polymer Optical Fibers (POFs)

The performance and suitability of an FBG sensor are heavily dependent on the material of the optical fiber. The two primary candidates are silica glass and polymer optical fibers, which exhibit distinct physical and optical properties.

Table 1: Material Properties Comparison of Silica and Polymer Optical Fibers

| Property | Silica Optical Fiber | Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) |

|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | ~70 GPa [6] | ~3 - 4 GPa [7] [6] |

| Fracture Toughness | Low (brittle) | High [2] |

| Elastic Strain Limit | <1% [6] | >6% - 15% [2] [7] |

| Bending Flexibility | Moderate | High [2] |

| Strain Sensitivity | Standard | Higher (approx. 15x more sensitive than silica) [7] |

| Biocompatibility | Good | Excellent, better compatibility with organic materials [2] |

| Safety | Can produce sharp shards if broken [2] [7] | Safer; no sharp shards [2] |

| Typical Material | Silica Glass (SiO₂) | Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) or CYTOP [2] |

Analysis of Material Differences

The data in Table 1 highlights a fundamental trade-off. Silica fibers are stiffer and more brittle but represent a mature, low-loss technology. Their high Young's Modulus makes them less sensitive to strain, as the same applied force results in less deformation. In contrast, Polymer Optical Fibers, typically made of PMMA, are far more flexible and compliant due to their lower Young's Modulus [6]. This compliance translates to a much higher strain sensitivity, as confirmed by one study where POF-based sensors exhibited at least 15 times higher sensitivity than their silica counterparts [7]. Furthermore, POFs are tougher, can withstand much larger deformations without breaking, and do not produce dangerous glass shards, making them inherently safer for use in close proximity to the human body [2] [7]. Their excellent biocompatibility and better compatibility with organic materials further solidify their advantage for biomedical applications [2].

Experimental Comparison: Performance in Biomedical Sensing

To objectively compare the performance of silica and polymer FBGs, it is essential to examine data from controlled experiments, particularly those simulating biomedical sensing scenarios.

Experimental Protocol for Vital Signs Monitoring

A key experiment demonstrating the capability of POF-FBGs involved monitoring human heartbeat and respiratory functions [7]. The methodology was as follows:

- FBG Inscription: A single-mode POF was fabricated using a unique core dopant, diphenyl disulphide (DPDS), which provides both high photosensitivity and increased refractive index. The FBG was inscribed using an ultraviolet laser (325 nm) and a phase mask in an extraordinarily short time of only 7 milliseconds [7].

- Sensor Interrogation: The sensor was connected to an interrogation system to monitor the Bragg wavelength shift in real-time.

- Subject Testing: The POF-FBG sensor was placed on a subject to detect chest wall movements caused by respiration and the subtle mechanical forces of the heartbeat.

- Signal Processing: A filtering protocol was implemented using a software program to extract the physiological signals. For respiration, a bandpass filter with low- and high-cut frequencies of 0.15 and 0.3 Hz, respectively, was applied. For the heartbeat, a filter with 2 and 8 Hz cutoffs was used [7].

- Comparison: The performance was qualitatively and quantitatively compared against a conventional silica FBG performing the same task.

Key Experimental Data and Results

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from this and other relevant experiments, directly comparing the two fiber types.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison for Biomedical Sensing

| Parameter | Silica FBG | Polymer FBG (POF-FBG) | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Sensitivity | ~1.2 pm/με [6] | Up to 180 pm/° [5] | Sensitivity for finger flexure sensing [5] |

| Pressure Sensitivity | ~3.04 pm/MPa (bare FBG) [8] | Much higher, exact multiple not specified [2] | Enhanced with mechanical transducers [8] |

| FBG Inscription Time | < 1 minute [7] | 7 milliseconds (with DPDS dopant) [7] | Enables mass production [7] |

| Vital Signs Monitoring | Possible, but risk of breakage [7] | Excellent; high sensitivity and safety [7] | Heartbeat and respiration monitoring [7] |

| Biomechanical Sensing | Used in tendons, ligaments [5] | Superior for soft tissue/internal strain [2] [5] | Spinal cord compression, menisci stress [5] |

| Key Advantage | Mature technology, wavelength encoded [2] | High elasticity, biocompatibility, safety [2] [7] |

The experimental data confirms the material analysis. The extremely fast inscription time for POF-FBGs is a breakthrough, paving the way for cost-effective, single-use, in vivo sensors [7]. Furthermore, the significantly higher strain sensitivity of POF-FBGs makes them indispensable for detecting subtle physiological movements, such as finger flexures or the internal strain of soft tissues like the spinal cord, where traditional silica sensors are too stiff and insufficiently sensitive [2] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers embarking on the fabrication and application of POF-based FBG sensors, the following reagents and materials are essential.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for POF-FBG Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Diphenyl Disulphide (DPDS) | A core dopant for POFs that provides ultra-high photosensitivity and increases the core refractive index, enabling rapid FBG inscription [7]. | Used in PMMA fiber core [7] |

| Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) | The primary base material for fabricating the polymer optical fiber itself [2] [7]. | Cladding material; also used for fiber core when combined with dopants [7] |

| Photopolymerizable Resin | Used for splicing and connecting POFs to silica fibers for light delivery and interrogation [6]. | NOA86H [6] |

| Phase Mask | A photolithographic component containing the periodic pattern used to inscribe the FBG into the fiber core with UV laser light [7]. | Ibsen phase masks [7] |

| UV Laser Source | The light source required to create the permanent refractive index modulation in the photosensitive fiber core [7] [1]. | He-Cd 325 nm laser [7] |

| Interrogator System | The instrument that sends broadband light into the fiber and detects the wavelength shift of the reflected Bragg signal [6]. | Micron Optics sm125-500 [6] |

The fundamental operating principle of Fiber Bragg Gratings—the reflection of a specific wavelength dictated by the Bragg condition—is universal. However, the material platform on which the FBG is built dramatically defines its performance and application potential. While silica FBGs are a robust and well-understood technology, the experimental data and material analysis conclusively show that Polymer Optical Fibers (POFs) offer superior characteristics for biomedical sensing. The combination of their lower Young's modulus, higher elastic strain limit, significantly greater strain sensitivity, and inherent safety makes POFBGs the more promising candidate for a new generation of wearable, implantable, and clinical monitoring devices. The rapid advancements in POF materials, such as the use of DPDS dopant for millisecond-scale grating inscription, are pushing the boundaries towards low-cost, highly sensitive, and disposable sensors that could profoundly impact future biomedical research and patient care.

In the field of biomedical sensing, the core composition of optical components, notably Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) and Silica Glass, fundamentally dictates the performance, applicability, and practicality of sensing devices. Optical fiber sensors, especially those based on Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs), are crucial for applications ranging from physiological monitoring to minimally invasive surgery due to their compact size, immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI), and high sensitivity [2] [9]. The choice between polymer and silica-based fibers is not merely a technical substitution but a strategic decision that influences the sensor's mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and integration into medical devices. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of PMMA and Silica Glass, framing their performance within the context of advancing biomedical sensing research and helping scientists select the optimal material for specific application requirements.

Fundamental Properties and Biomedical Relevance

The intrinsic properties of PMMA and Silica Glass make them suitable for distinct niches within biomedical sensing. PMMA, a synthetic polymer, offers high flexibility, a lower Young's modulus, and higher fracture toughness, making it exceptionally suitable for wearable sensors and applications requiring repeated flexion [9] [10]. Its higher elastic strain limits and impact resistance enhance durability in dynamic physiological environments. Furthermore, PMMA is generally considered to have superior biocompatibility and presents a lower risk of injury than silica glass, as it does not produce sharp shards upon failure [9] [11].

In contrast, Silica Glass is an inorganic material known for its excellent optical clarity and lower attenuation (signal loss), which is beneficial for applications requiring long-distance signal transmission [9]. However, its brittleness and higher Young's modulus can be a limitation in flexible or load-bearing biomedical applications. A critical advancement for PMMA has been the development of ultra-fast FBG inscription using novel dopants like diphenyl disulphide (DPDS), enabling grating inscription in as little as 7 milliseconds and paving the way for cost-effective, single-use, in vivo sensors [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Material Properties for Biomedical Sensing

| Property | PMMA (Polymer) | Silica Glass | Biomedical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | ~3-4 GPa [11] [12] | ~73 GPa [11] | PMMA is more flexible and compliant with biological tissues. |

| Strain Limit | Higher (≥1-6% yield strain) [10] | Lower | PMMA can withstand larger deformations, ideal for wearable devices. |

| Fracture Toughness | High [9] | Low; forms sharp shards [9] | POFs are safer for intrusive and wearable applications. |

| Typical Attenuation | Higher (e.g., ~0.2-2 dB/cm in NIR) [10] | Lower | Silica is better for long-distance transmission; POFs are suitable for short-range. |

| Biocompatibility | Generally high; safer upon breakage [9] [11] | Lower risk from leaching, but sharp fragments are a concern [9] | PMMA is often preferred for in-body, wearable, and textile-integrated sensors. |

| Key Advantage | Flexibility, high strain sensitivity, safety | Excellent optical transmission, maturity of technology | PMMA for dynamic, high-strain environments; Silica for precise, stable platforms. |

Comparative Performance Data in Sensing Applications

Experimental data consistently demonstrates that PMMA-based sensors exhibit a significantly higher sensitivity to strain and pressure compared to their silica counterparts. This makes them particularly advantageous for monitoring subtle physiological forces. For instance, one study confirmed that FBGs inscribed in PMMA fibers can exhibit at least a 15 times higher sensitivity than silica glass FBGs [11]. This enhanced sensitivity has been successfully leveraged for highly stringent monitoring, such as detecting a human heartbeat and respiratory functions directly from the body's surface [11].

The composite approach, where silica nanoparticles (SiO2) are incorporated into a PMMA matrix, is a prominent strategy to enhance the material's mechanical properties. Research on PMMA-SiO2 nanocomposites reveals that the silica nanoparticles act as stress dispersants, enhancing the hardness, tensile strength, and thermal stability of the base polymer [13]. This synergy is crucial for applications demanding dimensional stability and durability. However, a critical trade-off exists: an excessive concentration of SiO2 nanoparticles can lead to increased brittleness, reducing the material's overall strength and durability [13]. Therefore, optimizing nanoparticle concentration is essential, with studies on denture bases showing that incorporating 3-7% by weight of nano-silica can lead to highly significant improvements in impact strength, transverse strength, and hardness [12].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Key Studies

| Application / Test | Material Configuration | Key Performance Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital Signs Monitoring | FBG in DPDS-doped PMMA fiber | ≥15x higher sensitivity to heartbeat/respiration than silica FBG | [11] |

| Impact Strength | PMMA denture base with 7% wt nano-SiO2 | Significant enhancement in impact strength compared to pure PMMA | [12] |

| Transverse Strength | PMMA denture base with 7% wt nano-SiO2 | Significant enhancement in transverse strength compared to pure PMMA | [12] |

| Surface Hardness | PMMA denture base with 7% wt nano-SiO2 | Significant enhancement in surface hardness (Shore D) | [12] |

| Nanofiber Membranes | PMMA-SiO2 via microfluidic spinning | Enhanced tensile strength vs. traditional electrospinning; better nanoparticle dispersion | [13] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Ultra-Fast FBG Inscription in PMMA Fiber

This protocol enables the rapid production of highly sensitive PMMA-FBG sensors for biomedical applications [11].

- Fiber Fabrication: Fabricate a single-mode POF preform using the "pull-through" method. The cladding is made of pure PMMA, and the core is composed of PMMA (92% wt) doped with DPDS (8% wt). DPDS acts as both a refractive index modifier and a photosensitivity enhancer.

- Fiber Drawing: Draw the preform into a fiber at a temperature of approximately 220°C. The fiber used in the cited study had a diameter of 120 μm with a 5.5 μm core.

- Annealing: Anneal the drawn fiber at 80°C for 48 hours to relieve internal stresses induced during the drawing process.

- FBG Inscription: Place the annealed fiber on a V-groove and secure a phase mask (e.g., pitch of 1046.3 nm) directly above it with a small gap. Using a UV laser (e.g., 325 nm He-Cd laser) with an optical power of about 25.5 mW, expose the fiber through the phase mask for a duration of 7 milliseconds.

Protocol for Fabricating PMMA-SiO2 Nanofiber Membranes via Microfluidic Spinning

This method overcomes the limitations of electrospinning, such as nanoparticle agglomeration, resulting in superior mechanical properties [13].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a PMMA solution by dissolving PMMA pellets in N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) under magnetic stirring. Separately, prepare a SiO2 nanoparticle solution by dispersing nano-SiO2 in deionized water. The concentrations of both solutions should be varied systematically to optimize morphology.

- Microfluidic Spinning: Use a microfluidic chip with designed channel structures. Precisely pump the PMMA solution and the SiO2 dispersion as separate core and sheath fluids into the chip's inlets. The laminar flow within the microchannels allows for precise control over the composite fiber's structure.

- Fiber Formation & Collection: The combined fluid jet is extruded from the chip's outlet and collected by a rotating drum. The process parameters (e.g., flow rates, drum rotation speed) are adjusted to control fiber diameter and alignment.

- Post-processing & Characterization: Dry the collected nanofiber membranes thoroughly. Characterize the fibers using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphology and perform tensile tests to evaluate mechanical strength.

Protocol for Enhancing Denture Base PMMA with SiO2 Nanoparticles

This protocol demonstrates a common method for creating polymer-ceramic composites with enhanced mechanical performance [12].

- Nanoparticle Preparation: Obtain and characterize silica nanoparticles (e.g., from rice husk for amorphous silica or silica sand for crystalline). Confirm properties like size (e.g., 50-70 nm) and purity.

- Composite Fabrication: Incorporate the nano-SiO2 particles at different concentrations (e.g., 3%, 5%, and 7% by weight) into the liquid methyl methacrylate (MMA) monomer. Ensure the nanoparticles are well-dispersed using a magnetic stirrer.

- Mixing and Curing: Combine the modified monomer with PMMA powder following the manufacturer's recommended powder-to-liquid ratio. Pack the mixture into molds and process by conventional heat curing.

- Mechanical Testing: Prepare standardized test specimens from the cured composite. Conduct Charpy impact tests, three-point bending tests for transverse strength, and shore D hardness tests to quantify the improvement in mechanical properties.

Visualization of Workflows and Logical Relationships

FBG Sensing Principle and Signal Processing

The following diagram illustrates the working principle of a Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensor and the subsequent signal processing used to extract physiological information, such as heartbeat and respiration.

Material Selection Logic for Biomedical Sensors

This flowchart provides a logical framework for researchers to select between PMMA and Silica Glass based on the primary requirement of their specific biomedical sensing application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for POF and Silica Glass Sensing Research

| Item Name | Function / Role | Specific Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PMMA Powder & MMA Monomer | Base material for fabricating polymer optical fibers and composites. | High-purity, medical or injection grade (e.g., MW 100,000-120,000 g/mol). Sourced from chemical suppliers like Shanghai Aladdin [13]. |

| Diphenyl Disulphide (DPDS) | Core dopant for PMMA fibers to simultaneously enhance refractive index and photosensitivity for ultra-fast FBG inscription [11]. | Enables FBG inscription times as low as 7 ms. Critical for mass production of single-use sensors. |

| Silica Nanoparticles (SiO2) | Functional filler to create composite materials, enhancing mechanical strength, hardness, and thermal stability of PMMA [13] [12]. | Can be amorphous or crystalline. Key to avoid agglomeration. Typical sizes: 7-40 nm, with specific surface area of ~150 m²/g [13]. |

| Phase Mask | A critical optical component used in the FBG inscription process. It diffracts a UV laser beam to create a periodic interference pattern on the fiber core [11]. | Typically made of silica. The pitch (e.g., 1046.3 nm) determines the initial Bragg wavelength of the grating. |

| UV Laser System | Light source for the photo-inscription of Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs) in the fiber core. | He-Cd lasers at 325 nm are commonly used for PMMA fibers [11]. |

| Microfluidic Spinning System | Advanced fabrication system for producing composite nanofibers with precise control over internal structure and nanoparticle distribution [13]. | An alternative to electrospinning. Consists of precision pumps, a designed microfluidic chip, and a collection drum. |

The comparison between PMMA and Silica Glass reveals a clear trade-off: PMMA excels in mechanical flexibility, strain sensitivity, and safety for in-vivo and wearable biomedical sensing, while Silica Glass remains superior for applications demanding minimal optical signal loss and benefits from a mature fabrication ecosystem. The emerging trend of creating hybrid composites, such as PMMA-SiO2, demonstrates a powerful pathway to engineer materials that capture the benefits of both worlds—combining the flexibility and biocompatibility of polymers with the enhanced strength and stability of ceramic components. For researchers, the choice is application-defined. The development of ultra-fast FBG inscription technologies and advanced processing methods like microfluidic spinning will further empower scientists to tailor these core materials for the next generation of biomedical devices.

The advancement of biomedical sensing technology increasingly relies on the development of sophisticated materials that balance mechanical performance with biological compatibility. Fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors, which enable precise measurement of physiological parameters such as pressure, temperature, and strain, represent a critical technology in this field. These sensors can be fabricated on different fiber platforms, primarily silica glass and polymer optical fibers (POFs), which offer distinctly different material properties. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these two material systems, focusing on the key parameters of Young's Modulus, flexibility, and biocompatibility that determine their suitability for biomedical sensing applications. Understanding these fundamental property differences enables researchers to select the optimal material for specific biomedical sensing challenges, from implantable monitors to wearable diagnostic devices.

Material Properties Comparison

The core materials used in silica and polymer optical fibers exhibit fundamentally different characteristics that directly influence their performance in biomedical sensing applications. The following table summarizes these key properties for direct comparison.

Table 1: Comparative material properties of silica and polymer optical fibers for biomedical sensing

| Property | Silica Glass Fiber | Polymer Optical Fiber (PMMA) | Significance for Biomedical Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | ~73 GPa [11] | ~2-4 GPa [10] [11] | Determines stiffness and force required for deformation |

| Strain at Break | Low (brittle) | High (1-6% yield strain) [10] | Indicates durability under mechanical stress |

| Biocompatibility | Biocompatible but produces sharp shards [11] | Biocompatible, no sharp shards [11] | Safety for in-vivo and implantable applications |

| Flexibility | Low (high stiffness) | High (low Young's modulus) [10] | Suitability for flexible devices and bending applications |

| Density | Higher | Lower, lightweight [10] | Comfort for wearable devices |

| EMI Immunity | Innate immunity [8] [10] | Innate immunity [8] [10] | Reliability in electrically noisy environments |

The substantial difference in Young's Modulus, with POFs being approximately 18-36 times more flexible than silica fibers, represents the most significant differentiating factor. This mechanical property directly translates to enhanced strain sensitivity in polymer FBGs, which has been reported to be at least 15 times higher than their silica counterparts [11]. This increased sensitivity is particularly valuable for detecting subtle physiological signals such as heartbeat and respiratory functions [11].

For biomedical applications requiring direct patient contact or implantation, the safety profile of POFs is notably superior. Unlike silica fibers, which can produce sharp, hazardous shards when fractured, polymer fibers break without forming dangerous fragments, significantly reducing risk in the event of device failure [11].

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Determining Young's Modulus and Mechanical Properties

The characterization of mechanical properties for optical fiber materials follows standardized methodologies to ensure reproducible and comparable results.

Sample Preparation: Research-grade silica SMF (e.g., Corning SMF-28) and single-mode POF (e.g., PMMA with DPDS dopant) should be selected. For tensile testing, fiber samples of standardized lengths (typically 50-100 cm) must be prepared with care to avoid surface defects that could influence results. Prior to testing, POF samples should be annealed (e.g., at 80°C for 48 hours) to relieve internal stresses from the drawing process [11].

Tensile Testing Protocol:

- Mount fiber samples in a universal testing machine with specialized grips designed to prevent slippage without crushing the fiber.

- Apply tension at a constant strain rate (e.g., 5 mm/min) while simultaneously monitoring force and displacement.

- Use appropriate optical time-domain reflectometry (OTDR) or interferometric methods to simultaneously monitor optical transmission properties during mechanical testing.

- Record stress-strain curves until fiber failure.

- Calculate Young's Modulus from the linear elastic region of the stress-strain curve.

- For POFs, note the characteristic yield point and plastic deformation region before failure, which differs from the brittle fracture behavior of silica [10].

Biocompatibility Assessment

Biocompatibility evaluation ensures material safety for biomedical applications through standardized testing protocols.

Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5):

- Prepare fiber extracts by incubating sterilized fiber samples in cell culture medium at 37°C for 24 hours.

- Culture established cell lines (e.g., L-929 mouse fibroblasts) in appropriate conditions.

- Expose cells to fiber extracts for 24-72 hours.

- Assess cell viability using MTT assay or similar metabolic activity indicators.

- Compare results to negative and positive controls to determine cytotoxicity potential [11].

Direct Contact Testing:

- Place sterilized fiber samples directly onto cultured cell monolayers.

- Incubate for 24-48 hours at 37°C.

- Examine cells microscopically for morphological changes and zone of inhibition around samples.

- Score reactivity according to established biocompatibility standards [10].

Fragment Hazard Assessment:

- Deliberately fracture fiber samples under controlled conditions.

- Examine resulting fragments for shape, size, and sharpness.

- Document the potential for tissue damage from fragments [11].

Fabrication Techniques and Workflows

The production of fiber Bragg gratings in both silica and polymer fibers involves specialized fabrication processes that significantly influence their final properties and performance characteristics.

Table 2: Comparison of FBG fabrication techniques for silica and polymer fibers

| Fabrication Aspect | Silica Glass FBG | Polymer Optical Fiber FBG |

|---|---|---|

| Common Laser Sources | 248 nm KrF excimer, 193 nm ArF excimer [14] | 325 nm He-Cd, 248 nm KrF excimer, 266 nm Nd:YAG [14] |

| Standard Inscription Time | < 1 minute [11] | 7 ms to >1 hour (material-dependent) [11] |

| Photosensitivity Methods | Germanium doping, hydrogen loading [15] | Doping with DPDS, BDK, TS-DPS [14] [11] |

| Preform Fabrication | MCVD process [15] | "Pull-through" method, molding [11] |

| Fiber Drawing Temperature | ~1900-2100°C [15] | Lower temperature (thermal processing) [15] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages in the fabrication of polymer optical fiber Bragg gratings, highlighting the specialized processes required for successful fabrication:

A critical differentiator in POFB fabrication is the use of specialized dopants to enhance photosensitivity. Recent research has identified diphenyl disulphide (DPDS) as a particularly effective dopant that enables exceptionally fast FBG inscription times as short as 7 milliseconds [11]. This dramatic reduction in fabrication time opens possibilities for mass production and cost-effective, single-use biomedical sensors.

Sensing Performance in Biomedical Applications

The material properties of optical fibers directly influence their sensing performance in biomedical environments. The following diagram illustrates how the fundamental properties of POFs translate into functional advantages for biomedical sensing applications:

Experimental data demonstrates that POFBGs exhibit significantly higher sensitivity to physical parameters compared to silica FBGs. This enhanced sensitivity enables detection of subtle physiological signals, as demonstrated in research where POFBGs successfully monitored human heartbeat and respiratory functions with high precision [11]. The combination of higher flexibility and greater elasticity makes polymer fibers particularly suitable for integration into wearable sensing systems that must conform to body contours and withstand repeated deformation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Successful research and development in optical fiber biomedical sensing requires specific materials and reagents tailored to each fiber platform.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for optical fiber sensor development

| Material/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Silica SMF Preforms | Base material for silica fiber fabrication | Standard telecom fiber, silica FBG sensors [15] |

| PMMA Preforms | Base material for polymer optical fiber | Flexible POF sensors, strain sensing applications [11] |

| Germanium Dopants | Enhances silica photosensitivity | FBG inscription in silica fibers [15] |

| DPDS (Diphenyl Disulphide) | POF core dopant for photosensitivity & refractive index | Ultra-fast POFB inscription (7 ms) [11] |

| BDK Dopant | Photoinitiator for POFB fabrication | Enhancing POF photosensitivity [14] |

| Υ-MPS Coupling Agent | Surface modification of nanoparticles | Improving filler-matrix bonding in composites [16] [17] |

| Phase Masks | Pattern generation for FBG inscription | Defining grating period in FBG fabrication [14] |

| KrF Excimer Laser | UV source for FBG inscription | High-volume FBG production [14] |

The selection of appropriate dopants represents a particularly critical aspect of POFB development. While DPDS enables remarkably fast inscription times, other dopants like benzyl dimethyl ketal (BDK) offer alternative photosensitivity characteristics that may be preferable for specific applications [14]. The concentration of these dopants must be carefully optimized, typically in the range of 4-8% by weight, to balance photosensitivity with optical loss characteristics [11].

The comparative analysis of silica and polymer optical fibers for FBG-based biomedical sensing reveals a clear differentiation in their application domains. Silica fibers remain the preferred choice for applications demanding high thermal stability and established fabrication protocols. However, polymer optical fibers, particularly those based on PMMA with advanced dopants, demonstrate superior performance for biomedical sensing applications requiring high flexibility, enhanced strain sensitivity, and improved safety characteristics. The significantly lower Young's Modulus of POFs (approximately 2-4 GPa versus 73 GPa for silica) enables the development of more sensitive, compliant, and patient-friendly monitoring systems. Continued research in dopant engineering and fabrication optimization promises to further enhance the capabilities of POFBGs, potentially enabling new generations of disposable, implantable, and wearable biomedical sensors that safely and reliably monitor physiological parameters in diverse clinical and home-care settings.

Fiber-optic sensing technology has emerged as a cutting-edge research focus in the sensor field due to its miniaturized structure, high sensitivity, and remarkable electromagnetic interference immunity [8]. Compared with conventional sensing technologies, fiber-optic sensors demonstrate superior capabilities in distributed detection and multi-parameter multiplexing, thereby accelerating applications across biomedical fields [8]. Developments in fiber optic technology have had a significant impact on biomedical engineering applications, revolutionizing how engineers approach many aspects of these disciplines from faster, more accurate sensing to better communication [2]. Among the various optical fiber sensing technologies, Polymer Optical Fibers (POFs) and Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs) have garnered significant research interest, each offering distinct advantages for biomedical applications [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison between POF and silica-based FBG sensors, focusing on their performance relative to the critical biomedical requirements of EMI immunity, miniaturization, and corrosion resistance.

Fundamental Principles and Sensing Mechanisms

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) Sensing Technology

An FBG is a periodic modulation of the refractive index within the core of an optical fiber, typically created by exposing the fiber to ultraviolet laser light [18]. This periodic structure acts as a wavelength-specific filter, reflecting light at a particular wavelength, known as the Bragg wavelength (λB), while transmitting all other wavelengths [18]. The Bragg wavelength is determined by the spacing of the refractive index modulation (the grating period, Λ) and the effective refractive index (ηeff) of the fiber core, as defined by the equation: λB = 2ηeffΛ [18]. When external physical parameters such as strain or temperature change, they alter the grating period or the effective refractive index, resulting in a measurable shift in the Bragg wavelength [19]. This wavelength-encoded operation makes FBGs inherently self-referencing and independent of light source intensity fluctuations [2].

Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) Sensing Technology

Polymer Optical Fibers share many advantages with silica optical fibers, including low weight, immunity to EMI, and multiplexing capabilities [2]. POFs are fabricated from plastic polymers such as polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA) or amorphous fluorinated polymer (CYTOP) [2]. Despite higher transmission losses, POFs are generally cheaper than silica optical fibers and exhibit higher elastic strain limits, fracture toughness, bending flexibility, and increased strain sensitivity [2]. The excellent compatibility of polymers with organic materials gives them great potential for biomedical purposes [2]. POF sensors can operate based on various mechanisms including intensity modulation, bending losses, and evanescent field interactions [20].

Figure 1: Fundamental working principles and biomedical advantages of FBG and POF sensing technologies.

Comparative Performance Analysis: POF vs. Silica FBG

Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) Immunity

Table 1: EMI Immunity and Electrical Safety Comparison

| Parameter | POF Sensors | Silica FBG Sensors | Traditional Electronic Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMI Immunity | Inherently immune [2] | Inherently immune [8] [19] | Susceptible to noise [2] |

| Electrical Safety | Non-conductive, intrinsically safe [2] | Non-conductive, intrinsically safe [8] | Risk of electric shocks [2] |

| Operation in Explosive Environments | Safe [21] | Safe [8] | Requires extensive shielding [2] |

| Signal Integrity in MRI | Unaffected [2] | Unaffected [2] | Severe degradation |

Both POF and silica FBG sensors operate on optical principles, making them inherently immune to electromagnetic interference (EMI) [8] [2] [19]. This critical advantage enables reliable operation in biomedical environments rich in electromagnetic noise, such as those containing MRI equipment, electrosurgical units, or other medical instrumentation [2]. Unlike traditional electronic sensors that are susceptible to environmental noise and require complex shielding, optical fiber sensors maintain signal integrity without additional protective measures [2]. This immunity also eliminates the risk of electrical sparks, making both sensor types ideal for use in potentially explosive environments [21] and for invasive medical procedures where patient safety is paramount [2].

Miniaturization and Integration Potential

Table 2: Miniaturization and Mechanical Properties Comparison

| Parameter | POF Sensors | Silica FBG Sensors | Significance for Biomedicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Diameter | 0.25 - 1.0 mm [22] | 0.125 - 0.5 mm | Determines minimal invasiveness |

| Bending Flexibility | Excellent (high fracture toughness) [2] | Good (brittle, prone to breakage) [2] | Integration into textiles, wearable devices |

| Strain Limit | High (up to 10% or more) [2] | Moderate (~1-5%) [2] | Monitoring large joint movements |

| Biocompatibility | Favorable [2] | Good, but fragile [2] | Safety for implantable applications |

| Breakage Safety | Safe, no sharp fragments [2] | Risky, glass punctures possible [2] | Risk mitigation in vivo |

Miniaturization is crucial for biomedical applications, particularly for implantable devices, catheters, and minimally invasive surgical tools. While both technologies offer compact form factors, POFs demonstrate superior mechanical properties for certain applications. POFs exhibit higher elastic strain limits, fracture toughness, and bending flexibility compared to their silica counterparts [2]. This makes POFs significantly more robust against mechanical failure during installation and operation [2]. Furthermore, POFs are safer for use in smart textiles and intrusive applications, as silica fibers can break more easily, resulting in glass punctures that might cause injuries when they break [2]. The high flexibility of POFs enables their embedding into soft structures, making them suitable for instrumenting wearable robots and smart textiles [2].

Corrosion and Chemical Resistance

Table 3: Chemical and Environmental Resistance Comparison

| Parameter | POF Sensors | Silica FBG Sensors | Significance for Biomedicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture Resistance | Good (PMMA susceptible to hydrolysis) | Excellent | Long-term stability in bodily fluids |

| Chemical Resistance | Moderate (varies by polymer) | High (inert to most bodily fluids) | Compatibility with sterilization methods |

| pH Sensing Capability | Possible with functional coatings [22] | Possible with functional coatings [19] | Monitoring wound healing, body fluids |

| Corrosion Monitoring | Direct corrosion sensing possible [22] | Limited to indirect methods | Biomedical implant degradation |

| Functionalization | Easier surface modification | Requires specialized processing | Biosensing applications |

Both sensor types offer excellent resistance to corrosion compared to metallic sensors, but important differences exist. Silica fibers are highly inert and resistant to most chemicals found in biomedical environments [23]. POFs, depending on their material composition, may exhibit varying resistance to certain chemicals [2]. However, POFs demonstrate a significant advantage for direct corrosion monitoring applications. Research has successfully developed Fe-C film coated POF sensors for direct corrosion detection [22]. The polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) based POFs serve as effective host waveguides for such sensors, where the corrosion products induce measurable changes in the transmission properties of the fiber [22]. This capability is particularly relevant for monitoring biodegradable implants or metallic components within the body.

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 4: Experimental Performance Metrics for Biomedical Sensing

| Performance Metric | POF Sensor Results | Silica FBG Sensor Results | Testing Conditions & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Sensitivity | Higher strain sensitivity [2] | ~1.2 pm/με [24] | FBG useful for precise measurements, POF for large deformations |

| Pressure Sensitivity | Varies with design | 13.22 pm/kPa (3D-printed PLA embedded) [25] | 3D-printed embedding demonstrates integration potential |

| Temperature Sensitivity | Varies with polymer type | ~10 pm/°C [24] | Requires compensation in biomedical monitoring |

| Cost Factor | Lower cost [22] | Higher (interrogation systems) [19] | POF uses low-cost LEDs; FBG requires expensive demodulation |

| Multiplexing Capability | Supported (intensity-based) [20] | Excellent (wavelength-based) [8] | Multi-point monitoring for gait analysis, pressure mapping |

Experimental data demonstrates the complementary strengths of both technologies. FBGs offer high precision with strain sensitivity of approximately 1.2 pm/με and temperature sensitivity around 10 pm/°C [24]. Their wavelength-encoded nature facilitates excellent multiplexing capabilities, allowing multiple sensors on a single fiber [8]. POFs excel in applications requiring higher strain limits and greater flexibility [2]. From a cost perspective, POF systems are generally more economical, utilizing low-cost LEDs as light sources and offering simpler installation [22]. FBG systems typically involve higher costs, particularly for high-speed and high-precision demodulation equipment [24] [19].

Experimental Protocol: Corrosion Sensing with POF

Detailed Methodology from Cited Research: A study demonstrating Fe-C coated POF sensors for corrosion detection provides a representative experimental protocol [22]:

Sensor Fabrication: PMMA-based POFs with cladding/core diameters of 1.0 mm/0.98 mm were used. A 100-mm long protective coating in the middle part of the POF was removed to expose the cladding, which was subsequently removed using a polishing method with abrasive papers to enhance the evanescent field.

Functional Coating: Fe-C film was deposited on the polished section using a magnetron sputtering system with a pure iron target in an argon and acetylene gas mixture. Sensors with different coating thicknesses (25 μm, 30 μm, and 35 μm) were fabricated.

Accelerated Corrosion Testing: Sensors were characterized in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution using an impressed current technique to simulate accelerated corrosion conditions. The output optical power of the sensors was continuously monitored throughout the corrosion process.

Data Analysis: The relationship between the output response of the POF sensors and the corrosion-induced mass loss of steel bars was established. Sensors with thicker Fe-C coatings (35 μm) demonstrated a wider detection range and higher durability, showing a consistent and wide-range output response during the 5.5-hour accelerated corrosion test [22].

This experimental approach highlights how POF sensors can be functionalized for specific biomedical applications, such as monitoring the corrosion of metallic implants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Materials and Components for Optical Fiber Biomedical Sensors

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PMMA-based POF | Core sensing element; provides flexibility and high strain limit [2] [22] | Wearable sensors, smart textiles, large deformation monitoring |

| Silica Optical Fiber | Core sensing element for FBG; provides high precision and stability [18] | Precise physiological parameter monitoring (pressure, strain) |

| UV/Femtosecond Laser | Inscription of periodic refractive index modulation in FBG [19] [18] | Fabrication of Fiber Bragg Gratings |

| Fe-C Coating | Functional material for direct corrosion sensing [22] | Monitoring degradation of metallic implants |

| pH-Sensitive Gel/Hydrogel | Functional coating for biochemical sensing [19] | Monitoring pH changes in wounds or body fluids |

| 3D Printing Materials (PLA, TPU) | Customizable sensor packaging and substrates [25] | Fabrication of wearable sensor housings, anatomical interfaces |

| Optical Interrogator | Instrument for detecting wavelength shifts in FBG sensors [24] | Signal demodulation in FBG-based monitoring systems |

| LED/Laser Source | Light source for transmitting optical signals through the fiber [22] | Illumination for both POF and FBG sensor systems |

Application Scenarios in Biomedicine

Figure 2: Technology selection guide for biomedical applications based on sensor requirements.

The choice between POF and silica FBG sensors depends heavily on the specific biomedical application. POF sensors are particularly suited for applications requiring high flexibility, large deformation monitoring, and cost-effective solutions [2]. Their safety and durability make them ideal for wearable devices, smart textiles, robotic rehabilitation instrumentation, and plantar pressure measurement systems [2] [24]. The excellent compatibility of polymers with organic materials further enhances their potential for biomedical purposes [2].

Silica FBG sensors excel in applications demanding high precision, multi-parameter sensing, and operation in high-temperature environments [8] [2]. They have been successfully employed in cardiac surgery for blood pressure monitoring, cancer treatment procedures, and as sensors mounted on surgical tools for force feedback [2]. Their wavelength-encoded nature facilitates multiplexing, allowing multiple sensors (e.g., for temperature, pressure, and strain) to be integrated into a single fiber for comprehensive physiological monitoring [8].

Both POF and silica FBG technologies offer significant intrinsic advantages for biomedical sensing, including unparalleled EMI immunity, miniaturization potential, and corrosion resistance. The optimal selection between these technologies involves careful consideration of application-specific requirements. POF sensors present superior flexibility, higher fracture toughness, and greater safety against breakage, making them ideal for wearable applications and environments requiring large deformations. Their cost-effectiveness further enhances accessibility for large-scale or disposable medical applications. Silica FBG sensors offer higher precision, excellent multiplexing capabilities, and robustness in high-temperature environments, making them suitable for precise physiological parameter monitoring and multi-parameter sensing. Ongoing advancements in materials science, including the development of novel polymer composites and specialized fiber coatings, along with improvements in interrogation systems, continue to expand the capabilities and applications of both sensing platforms in biomedical engineering.

High Strain Sensitivity and Break Resistance

The selection of an appropriate sensing material is critical in biomedical research, where measurements often occur within dynamic biological environments. Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) and silica-based Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors present a compelling comparison. While silica FBGs are a mature technology known for their high precision, POFs are gaining prominence for applications requiring high flexibility, large strain measurement, and enhanced safety in human proximity. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two technologies, focusing on the core properties of strain sensitivity and break resistance, which are paramount for biomechanical monitoring, wearable devices, and implantable sensors. The inherent material properties of polymers, such as a lower Young's modulus and higher elastic strain limit, fundamentally differentiate POF performance from its silica counterparts [2] [26] [14].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize key experimental data comparing the mechanical and sensing properties of POF and silica FBG sensors, providing a foundation for objective evaluation.

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Material and Sensing Properties

| Property | Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) FBG | Silica Optical Fiber FBG | Significance in Biomedical Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | ~2-4 GPa [7] [14] | ~70-73 GPa [7] [27] | Lower modulus enables higher flexibility and conformability to soft tissues. |

| Strain at Fracture | >15% (Highly flexible) [2] [14] | ~1-3% (Brittle) [2] | Higher fracture tolerance ensures sensor integrity under large or unexpected deformations. |

| Strain Sensitivity | ~1.5 pm/με [27] | ~1.2 pm/με [27] | Higher sensitivity allows for detection of subtler physiological movements and strains. |

| Typical Pressure Sensitivity | Can exceed 175.5 pm/kPa [28] [8] | Typically ~3-4 pm/MPa (bare fiber) [28] [27] | Greatly enhanced response to physiological pressures (e.g., blood pressure, tissue compression). |

| Biocompatibility & Safety | High flexibility; does not produce sharp shards [2] [7] | Rigid; can produce sharp shards upon breakage, posing a safety risk [2] [7] | Safer for use in wearables and in vivo applications; more compatible with organic materials [2]. |

Table 2: Experimental Sensor Performance Data from Cited Literature

| Sensor Type & Configuration | Key Performance Metric | Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etched POF FBG (Dia: 85µm) [26] | Pressure Sensitivity | 43.7 to 175.5 pm/kPa | Sensor tested in blood pressure range using an epoxy diaphragm. |

| Silica FBG (Bare Fiber) [28] [8] | Pressure Sensitivity | ~3.04 pm/MPa | Baseline response, highlighting need for mechanical transduction. |

| POF-based Intensity Sensor (Twisted-Bend) [29] | Pressure Sensitivity | 432.21 nW/MPa | High-pressure sensing up to 4 MPa, demonstrating mechanical robustness. |

| DPDS-doped POF FBG [7] | Inscription Time | 7 ms | Ultra-fast fabrication compared to minutes or hours for earlier POFs. |

| POF FBG [7] | Strain Sensitivity (vs. Silica) | At least 15x higher | Demonstrated in human heartbeat and respiration monitoring. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Enhancing Intrinsic POF Sensitivity via Etching

Solvent etching is a demonstrated method to intrinsically enhance the sensitivity of POFBGs by altering the fiber's material and mechanical properties [26].

- Objective: To reduce the fiber diameter and lower the Young's modulus, thereby increasing the intrinsic sensitivity to strain, temperature, and pressure.

- Materials:

- Single-mode POF (e.g., PMMA core with BzMA dopant).

- Etching solution: A 1:1 combination of acetone and methanol.

- Diameter measurement setup (e.g., microscope).

- Procedure:

- Prepare the etching solution in a controlled fume hood.

- Immerse a section of the POF into the solution for a controlled duration.

- Remove the fiber and measure the etched diameter to achieve target values (e.g., from 180 µm down to 70 µm [26]).

- Inscribe an FBG in the etched region using a phase mask and UV laser (e.g., He-Cd laser at 325 nm).

- Key Parameters: Etching time and solvent ratio control the diameter reduction and final mechanical properties. Research shows that etching can increase the thermal expansion coefficient and decrease Young's modulus, directly boosting sensitivity [26].

High-Speed POF FBG Inscription for Mass Production

Recent advances in dopant materials have enabled inscription speeds that make mass production of single-use biomedical POFBGs feasible.

- Objective: To inscribe an FBG in a POF on a millisecond timescale.

- Materials:

- Single-mode POF with a highly photosensitive core dopant (e.g., Diphenyl Disulphide - DPDS).

- UV laser system (e.g., 325 nm He-Cd laser).

- Phase mask, beam shutter, and cylindrical lens.

- Procedure:

- Fabricate a POF preform using the "pull-through" method, with a PMMA cladding and a DPDS-doped PMMA core [7].

- Draw the fiber to the desired diameter (e.g., 120 µm).

- Anneal the fiber to remove drawing-induced stress.

- Place the fiber on a V-groove in close proximity to a phase mask.

- Focus the UV beam through a cylindrical lens to create a 12-mm-long elliptical beam on the fiber.

- Control the irradiation time using a beam shutter; a 7 ms exposure is sufficient to inscribe a strong FBG with a DPDS-doped fiber [7].

- Key Parameters: The core dopant is critical for achieving high photosensitivity. This rapid process allows for potential inscription during the fiber drawing process itself.

Visualization of Working Principles and Properties

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows behind POF sensing technology.

Diagram 1: POF FBG Sensing Principle. This workflow shows how external pressure causes a more significant deformation in a POF due to its low Young's Modulus, leading to a larger Bragg wavelength shift and higher sensitivity output compared to silica. The safety property of producing no sharp shards is a direct result of the material.

Diagram 2: POF FBG Fabrication Workflow. The key steps in creating a high-sensitivity POFBG sensor, from preform fabrication to FBG inscription, highlighting the optional etching step for intrinsic sensitivity enhancement and the critical materials required at each stage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers developing POF sensors for biomedical applications, the following materials and reagents are essential.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for POF FBG Sensor Development

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Core Dopants | Enhance photosensitivity for efficient FBG inscription. | Diphenyl Disulphide (DPDS): Enables ultra-fast grating inscription (7 ms) [7]. Benzyl Methacrylate (BzMA): Used to achieve required core refractive index [26]. |

| Etching Solvents | Modify fiber diameter and mechanical properties to boost intrinsic sensitivity. | Acetone/Methanol (1:1 mix): Provides a controlled etching rate for PMMA fibers [26]. |

| UV Laser Systems | Inscribe the periodic grating structure into the fiber core. | He-Cd Laser (325 nm): Commonly used for POF inscription [26] [7]. KrF Excimer Laser (248 nm): Also employed for rapid inscription [14]. |

| Single-Mode POF | The base sensing medium, required for well-defined FBG spectra. | PMMA-based fibers: The most common material, though single-mode varieties require precise fabrication [2] [27]. Microstructured POFs (mPOFs): Designed with air holes to guide light, facilitating single-mode operation [14]. |

| Interrogation System | Detect and measure the wavelength shift from the FBG. | Optical Spectrum Analyzer (OSA): For characterizing reflection/transmission spectra. High-Speed Interrogator: Essential for dynamic physiological monitoring (e.g., heartbeat) [7]. |

Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs) have emerged as a transformative technology in the field of biomedical sensing, offering unprecedented capabilities for measuring physiological parameters such as temperature, strain, pressure, and chemical biomarkers. Within this domain, a significant comparison exists between FBGs fabricated in traditional silica glass fibers and those inscribed in polymer optical fibers (POFs). Silica-based FBGs bring distinct advantages to biomedical applications, primarily their high thermal stability and mature fabrication processes developed over decades of refinement. These characteristics make them particularly suitable for medical procedures involving elevated temperatures or requiring highly standardized, reproducible sensor production. This guide provides an objective comparison between silica and polymer FBG technologies, focusing on their properties, performance metrics, and suitability for various biomedical sensing applications, with particular emphasis on the established advantages of silica FBGs.

Fundamental Principles and Material Properties

Working Principle of FBGs

An FBG is a periodic modulation of the refractive index within the core of an optical fiber. This structure acts as a wavelength-specific mirror, reflecting a narrow band of light at a characteristic Bragg wavelength (λ𝐵) while transmitting all other wavelengths. The Bragg wavelength is given by the equation:

λ𝐵 = 2𝑛ₑ𝒻𝒻Λ

where 𝑛ₑ𝒻𝒻 is the effective refractive index of the fiber core and Λ is the grating period [14]. When the fiber is subjected to external stimuli such as mechanical strain or temperature changes, both 𝑛ₑ𝒻𝒻 and Λ are altered, resulting in a measurable shift in λ𝐵. This wavelength-encoded operation makes FBGs inherently immune to intensity fluctuations and enables multiplexing of several sensors on a single fiber [2].

Inherent Material Characteristics

The fundamental differences between silica and polymer FBGs stem from their base material properties, which dictate their performance in biomedical environments.

Table 1: Core Material Properties of Silica and Polymer Optical Fibers

| Property | Silica Glass | PMMA Polymer | CYTOP Polymer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | ~73 GPa [7] | ~3.2 GPa [30] | Information Missing |

| Failure Strain | <5% (brittle) | High (>10%) [2] | Information Missing |

| Thermo-Optic Coefficient (dn/dT) | Positive [31] | Negative and larger in magnitude [32] | -5.0 × 10⁻⁵/°C [31] |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient | Positive [31] | Positive [31] | 7.4 × 10⁻⁵/°C [31] |

| Biocompatibility | Can cause chronic inflammation [30] | Biocompatible [30] | Information Missing |

| Breakage Safety | Produces sharp shards [7] | Safer; no glass punctures [2] | Information Missing |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Thermal Stability and Response

Thermal performance is a critical differentiator. Silica FBGs exhibit exceptional thermal stability, with operational ranges extending to hundreds of degrees Celsius, far surpassing most biomedical requirements. Their Bragg wavelength shift with temperature is governed by:

Δλ𝐵/λ𝐵 = (α + ζ)Δ𝑇

where α is the thermal expansion coefficient and ζ is the thermo-optic coefficient [5]. Both coefficients for silica are positive, leading to a consistent positive wavelength shift with increasing temperature [31].

In contrast, the thermal response of POFBGs is more complex. Polymers like PMMA have a negative thermo-optic coefficient that counteracts the positive thermal expansion, often resulting in a net negative temperature sensitivity [32]. More importantly, standard polymer fibers face a fundamental limitation due to low glass transition temperatures (T𝑔). For instance, PMMA-based FBGs are typically limited to below 92°C, while even advanced polymers like ZEONEX 480R have an upper limit near 123°C [33]. This restricts their use in medical applications involving sterilization or high-temperature therapies.

Mechanical Sensitivity and Cross-Sensitivities

Mechanically, POFs possess a lower Young's modulus, making them more flexible and conferring higher sensitivity to strain and pressure—up to 15 times more sensitive than silica in some configurations [7]. This is advantageous for sensing subtle physiological forces. However, a significant challenge for many polymers (e.g., PMMA) is their hydrophilic nature, which causes humidity cross-sensitivity. Water absorption leads to fiber swelling, inducing Bragg wavelength shifts that can obscure other measurements unless carefully compensated [31]. Newer polymers like CYTOP and ZEONEX are being developed with low moisture affinity to mitigate this issue [33]. Silica fibers, being impervious to moisture, do not suffer from this effect.

Table 2: Experimentally Measured Performance Comparison of Silica and Polymer FBG Sensors

| Performance Parameter | Silica FBG | POFBG (PMMA) | POFBG (CYTOP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Temperature Sensitivity | ~10 pm/°C [31] | -37 to -134 pm/°C [31] | 27.5 pm/°C [31] |

| Typical Strain Sensitivity | ~1.2 pm/με | Higher than silica [2] | Information Missing |

| Humidity Sensitivity | Insensitive | 39 pm/%RH (at 25°C) [31] | 10.3 pm/%RH [31] |

| Maximum Operational Temperature | >500°C | ~92°C [33] | Information Missing |

| Fracture Toughness | Low (Brittle) | High [31] | Information Missing |

Fabrication Processes and Technological Maturity

The fabrication of silica FBGs is a mature field, benefiting from decades of development driven by the telecommunications industry. Standardized processes using 248 nm excimer lasers allow for rapid and highly reproducible inscription of high-quality gratings directly during the fiber drawing process, enabling mass production at low cost [2].

The fabrication of POFBGs has historically been more challenging. Inscription times with 325 nm lasers could take tens of minutes, requiring extreme mechanical stability [32]. Recent breakthroughs, such as the use of dopants like diphenyl disulfide (DPDS), have dramatically reduced inscription times to as low as 7 milliseconds using a 325 nm laser [7]. Alternative approaches using 248 nm excimer lasers with low fluence have also achieved inscription times of a few seconds in undoped microstructured POFs [32]. Despite these advances, the technology is less standardized than its silica counterpart.

Diagram 1: A simplified comparison of the fundamental fabrication workflows for Silica and Polymer Optical Fiber FBGs.

Experimental Protocols for Performance Characterization

To objectively compare the performance of silica and polymer FBGs, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols. The following outlines a general methodology for characterizing temperature and strain response, which are critical parameters for biomedical sensors.

Temperature Sensitivity Characterization

Objective: To determine the Bragg wavelength shift (Δλ𝐵) as a function of temperature change (Δ𝑇) and calculate the temperature sensitivity (𝐾𝑇 = Δλ𝐵/Δ𝑇).

Materials and Equipment:

- FBG sensor (silica or polymer).

- High-precision optical interrogator (e.g., Micron Optics sm125) with wavelength accuracy of 1 pm [33].

- Temperature-controlled oven or hot plate with a calibrated external thermocouple [33].

- Computer with data acquisition software (e.g., LabVIEW).

Procedure:

- Place the FBG sensor inside the oven, ensuring it is free from mechanical strain.

- Connect the FBG to the optical interrogator and position the thermocouple near the grating.

- Program the oven to ramp the temperature from a starting point (e.g., 25°C) to a target temperature at a controlled rate (e.g., 1°C/min) [33].

- Simultaneously record the Bragg wavelength and the actual temperature from the thermocouple at regular intervals.

- Plot the Bragg wavelength shift against temperature. The slope of the linear fit to this data yields the temperature sensitivity 𝐾𝑇.

Strain Sensitivity Characterization

Objective: To determine the Bragg wavelength shift (Δλ𝐵) as a function of applied strain (Δε) and calculate the strain sensitivity (𝐾𝜀 = Δλ𝐵/Δε).

Materials and Equipment:

- FBG sensor.

- Optical interrogator.

- Precision translation stage to apply controlled strain.

- Strain gauge for independent verification (optional).

Procedure:

- Fix both ends of the FBG sensor to the translation stage.

- Connect the FBG to the interrogator.

- Gradually increase the applied strain in small, known increments using the translation stage.

- Record the Bragg wavelength at each strain increment.

- Plot the Bragg wavelength shift against the applied strain. The slope of the linear fit provides the strain sensitivity 𝐾𝜀.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for POFBG Research and Fabrication

| Item | Function/Description | Relevance in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Diphenyl Disulfide (DPDS) | A photosensitive dopant for POF cores. | Enables ultra-fast FBG inscription (e.g., 7 ms) by providing both high refractive index and photosensitivity [7]. |

| Benzyl Dimethyl Ketal (BDK) | A photoinitiator dopant for POF cores. | Enhances the photosensitivity of the polymer, facilitating more efficient grating inscription with UV light [14]. |

| ZEONEX (E48R/480R) | A cyclo olefin polymer for POFs. | Offers low moisture absorption and higher thermal stability (up to ~123°C), reducing humidity cross-sensitivity [33]. |

| CYTOP | An amorphous fluorinated polymer. | Features low optical attenuation and a different thermo-optic response, allowing for tunable temperature sensitivity [31]. |

| 248 nm KrF Excimer Laser | Ultraviolet laser source. | Used for rapid (seconds) FBG inscription in both silica and certain polymer fibers [32] [33]. |

| 325 nm He-Cd Laser | Ultraviolet laser source. | A commonly used laser for POFBG inscription, especially with doped fibers [14] [7]. |

Silica FBGs remain a cornerstone of optical sensing due to their proven thermal resilience and highly mature, economical fabrication pathways. Their stability and insensitivity to humidity make them a reliable choice for many biomedical applications, particularly those not involving direct, flexible implantation. Conversely, POFBs offer a compelling alternative where high mechanical sensitivity, inherent flexibility, and enhanced biocompatibility are the primary concerns. While challenges remain regarding their thermal limits and humidity cross-sensitivity for some materials, ongoing research in new polymers and fabrication techniques is rapidly advancing their capabilities. The choice between the two technologies is not a matter of superiority but of application-specific suitability, with silica offering rugged reliability and polymers enabling a new generation of soft, sensitive, and integrated biomedical sensors.

Biomedical Application Methodologies: From Vital Signs to Biochemical Sensing

The accurate monitoring of vital signs—such as heartbeat, respiration, and body temperature—is fundamental to clinical care, physiological research, and drug development. Fiber optic sensor technology has emerged as a powerful tool for these applications, offering significant advantages over conventional electronic sensors, including inherent immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI), biocompatibility, and the ability to perform multiplexed and distributed sensing [9] [34]. Among these sensors, two primary technologies have garnered significant research interest: silica-based Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs) and Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) sensors. Silica FBGs represent a more mature technology, while POFs offer distinct material advantages that make them particularly suitable for specific biomedical applications [9] [10]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two sensing platforms, focusing on their performance in physiological monitoring, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers and scientists in the field.

Silica Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs) are created by introducing a periodic modulation of the refractive index in the core of a silica optical fiber. This structure reflects a specific wavelength of light, known as the Bragg wavelength (( \lambdaB )), which is given by ( \lambdaB = 2n{eff}\Lambda ), where ( n{eff} ) is the effective refractive index and ( \Lambda ) is the grating period [34]. External physical parameters such as strain and temperature directly affect ( n{eff} ) and ( \Lambda ), causing a shift in ( \lambdaB ) that can be precisely measured [35]. This mechanism allows FBGs to function as highly sensitive sensors for heartbeat (via arterial pulse waveform) and respiration (via chest wall movement) [34].

Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) sensors, particularly those made from materials like poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) or cyclic transparent optical polymer (CYTOP), leverage the inherent properties of polymers. These materials are characterized by high flexibility, a lower Young's modulus, and higher fracture toughness compared to silica glass [9] [10]. These mechanical properties make POFs more sensitive to mechanical deformations and less prone to catastrophic failure, which is a critical safety consideration in wearable and implantable devices [9]. Furthermore, some polymers are biocompatible and can be engineered to be responsive to specific biochemical stimuli [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Silica FBG and POF Sensing Platforms

| Characteristic | Silica FBG | POF Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| Core Material | Silica (glass) | Polymeric material (e.g., PMMA, CYTOP) |

| Young's Modulus | ~70 GPa [10] | ~2-3 GPa (PMMA) [10] |

| Strain Limit | ~1% (typically) [9] | >5% (can be much higher) [9] |

| Key Advantages | Mature fabrication, low optical loss | High flexibility, superior impact resistance, higher strain sensitivity, safer in wearables |

| Primary Sensing Mechanism | Wavelength shift of reflected light (( \Delta \lambda_B )) | Wavelength or intensity modulation in response to strain, temperature, or chemical changes |

Performance Data in Physiological Sensing

Experimental data from research demonstrates the capabilities of both sensor types in capturing vital signs. The following table summarizes key performance metrics reported in the literature.

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Physiological Monitoring Applications

| Monitoring Parameter | Sensor Type | Experimental Performance & Sensitivity | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial Pulse Waveform | Polymer FBG | Larger wavelength shift for a given strain due to lower Young's modulus, enhancing pulse waveform detail capture [34]. | Softer polymer FBGs are more sensitive to the subtle mechanical strains of arterial pulsation than traditional silica FBGs [34]. |

| Heartbeat & Pulse | Silica FBG | Wavelength shift demodulation captures pulse wave via skin surface mechanical changes [34]. | FBGs measure reflected wavelength, making them robust against optical power fluctuations, suitable for long-term monitoring [34]. |

| Humidity (Respiration) | Polymer FBG (PMMA-based) | Resolution increased by two orders of magnitude using microwave photonic filtering vs. direct OSA reading [36]. | The hygroscopic nature of PMMA allows for extremely high-resolution humidity sensing, directly applicable to respiration monitoring [36]. |

| Temperature | Silica FBG | Used in simultaneous temperature/strain measurement; machine learning minimizes cross-sensitivity error [37]. | A primary measurand for FBGs; cross-sensitivity with strain is a major challenge addressed via advanced interrogation [37]. |

| Simultaneous Strain & Temperature | Etched Silica FBG + Machine Learning | RMSE of 1.28 °C (temperature) and 11.3 µε (strain) achieved, minimizing cross-sensitivity vs. traditional matrix inversion [37]. | Machine learning interrogation successfully decouples cross-sensitive parameters, enabling high-accuracy multi-parameter sensing [37]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of the experimental groundwork behind the data, this section outlines two key methodologies cited in the comparison.

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Based Interrogation for Simultaneous Temperature and Strain Measurement

This protocol details the approach used to achieve high-accuracy, low cross-sensitivity measurement, a critical requirement in physiological monitoring where strain (from movement or pulse) and temperature often coexist [37].

- Sensor Preparation: An etched FBG sensor is used in conjunction with a single-multi-single mode (SMS) fiber structure, which serves as an edge filter for interrogation purposes [37].

- Data Acquisition: An experimental setup is meticulously constructed to subject the FBG to controlled levels of temperature and strain simultaneously. The Bragg wavelength shift and the corresponding change in optical power level are recorded to build a comprehensive labeled dataset [37].

- Model Training: The collected dataset is used to train an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model. The model is optimized by tuning the number of layers and neurons to map the complex, non-linear relationship between the input optical signals and the output parameters (temperature and strain) [37].

- Validation and Testing: The trained ANN model is validated against test data and its performance is compared to the conventional transfer matrix method, demonstrating a significant reduction in measurement error and cross-sensitivity [37].

Protocol 2: High-Resolution Humidity Sensing for Respiration Monitoring

This protocol describes a method for dramatically enhancing the resolution of a POFBG humidity sensor, which is directly applicable to monitoring human respiration [36].

- Sensor Setup: A PMMA-based POFBG and a reference silica FBG are employed as sensing probes. The PMMA fiber is hygroscopic and sensitive to humidity, while the silica FBG is not [36].

- Interrogation System: A two-tap microwave photonic filter (MPF) is implemented instead of a traditional optical spectrum analyzer (OSA). The POFBG and silica FBG introduce wavelength-dependent delays in the MPF [36].

- Signal Conversion: The humidity-induced wavelength shift in the POFBG is converted into a change in the free spectral range (FSR) of the microwave photonic filter's frequency response [36].