Polymer Optical Fiber Sensing in Biomechanics: Advanced Technologies for Healthcare Monitoring and Rehabilitation

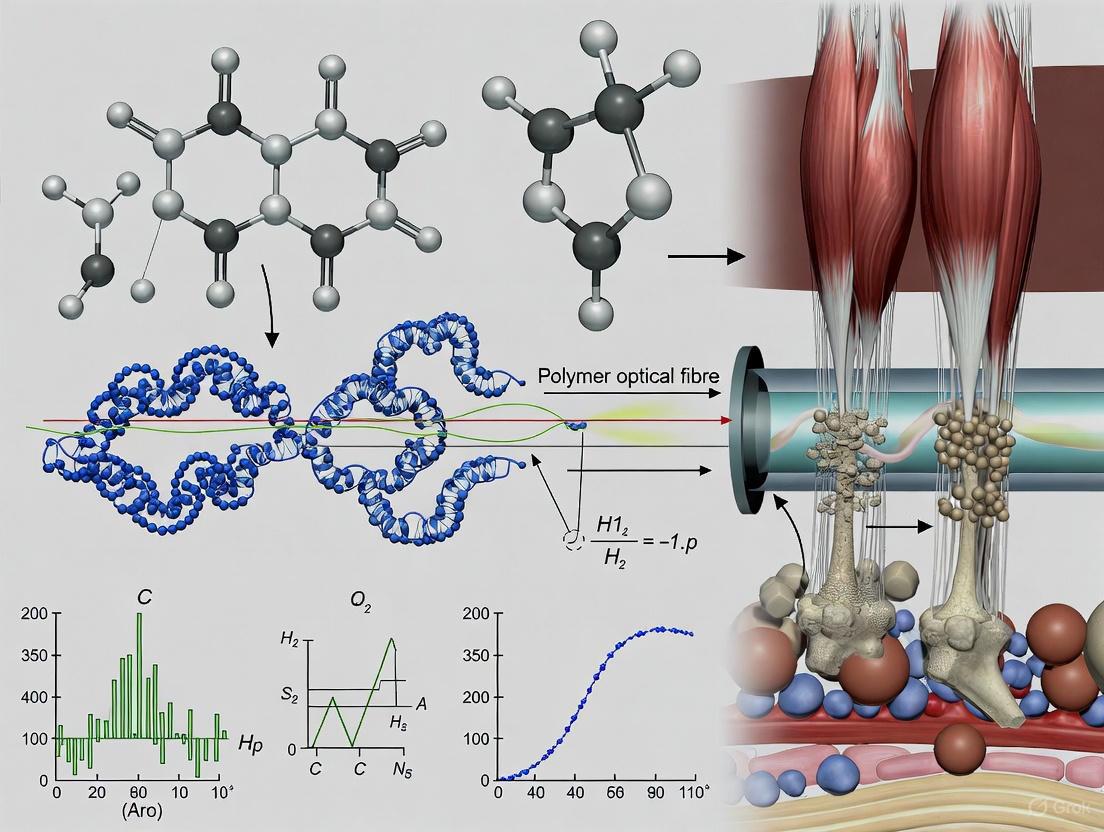

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of polymer optical fiber (POF) sensing technology and its transformative applications in biomechanics and biomedical engineering.

Polymer Optical Fiber Sensing in Biomechanics: Advanced Technologies for Healthcare Monitoring and Rehabilitation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of polymer optical fiber (POF) sensing technology and its transformative applications in biomechanics and biomedical engineering. Targeting researchers, scientists, and healthcare technology developers, the article systematically examines the fundamental principles of POF sensors, including Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs), intensity-based systems, and advanced sensing mechanisms. The content covers diverse biomedical applications from wearable robotics and gait analysis to physiological monitoring and chemical sensing. Through detailed analysis of performance optimization, validation methodologies, and comparative assessment with conventional sensing technologies, this article provides crucial insights for developing next-generation healthcare monitoring systems, rehabilitation devices, and clinical diagnostic tools that leverage the unique advantages of POF technology.

Fundamental Principles and Advantages of Polymer Optical Fiber Sensing Technology

Material Properties of Polymer Optical Fibers

Polymer Optical Fibers (POFs) are a class of optical fibers fabricated from high-transparency polymers, typically featuring a polymer core surrounded by a cladding made of a lower-refractive-index polymer material [1]. The fundamental working principle of POFs is based on total internal reflection, which allows them to transmit light through their core for both illumination and data transmission [2]. Their material composition grants them a unique set of mechanical and optical properties that distinguish them from traditional silica glass fibers.

Composition and Mechanical Characteristics

The most common materials for POFs are Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) for the core and fluorinated polymers for the cladding [1] [2]. Another high-performance material is amorphous fluoropolymer, commercially known as CYTOP, which is used to create Graded-Index POF (GI-POF) with superior transmission properties [3] [2]. The mechanical properties of POFs, including Young's modulus, strain, stress, and strength, are critically important for their performance and vary drastically depending on the POF type, such as step-index (SI-POF), microstructured POF (mPOF), multicore POF (MCPOF), or dye-doped POFs [4].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of common POF materials.

Table 1: Key Material Properties and Characteristics of Polymer Optical Fibers

| Property | PMMA (Standard SI-POF) | CYTOP (GI-POF) | Comparison to Silica Glass Fiber |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Material | Polymethyl methacrylate [2] | Amorphous fluoropolymer [3] | Silica glass |

| Refractive Index (Core) | 1.492 [1] | ~1.42 [2] | ~1.45 (core) |

| Typical Core Diameter | 0.98 mm / 0.735 mm / 1 mm [3] [2] | Smaller dimensions than PMMA POF [3] | 4-8 μm (SMF); 50/62.5 μm (MMF) [3] |

| Attenuation/Loss | ~1 dB/m @ 650 nm [2]; 0.15 dB/m @ 650 nm [3] | Low attenuation and scattering losses [3] | 0.2 dB/km @ 1550 nm [3] |

| Bandwidth | ~5 MHz·km @ 650 nm [2] | Enables Gigabit transmission speeds [2] | >10 GHz·km (SMF) |

| Primary Mechanical Advantages | High mechanical elasticity, high fracture toughness, high bending flexibility, ease of processing, vibration resistance, water resistance [1] [4] | High flexibility, reliability, and bending resistance [3] | High tensile strength, but intrinsically stiff and brittle [3] |

| Young's Modulus | ~3.2 GPa for PMMA [3] | Information Missing | ~70 GPa |

| Failure Strain | High failure strain [3] | Information Missing | Low failure strain |

Key Performance Advantages and Limitations

The material properties of POFs translate into several key operational advantages, particularly for sensing applications.

- Robustness and Flexibility: POFs are significantly more robust under bending, stretching, and vibration than silica fibers due to their high fracture toughness and elastic strain limit [2] [3] [1]. This makes them ideal for applications in dynamic environments.

- Ease of Handling and Installation: The large core diameter and high numerical aperture (NA) make POFs easy to align, connect, and install, requiring less precision than silica fibers [1] [3]. This also results in high coupling efficiency with light sources.

- Electromagnetic Immunity: Being dielectric, POFs are inherently immune to electromagnetic interference (EMI), making them suitable for use in electrically noisy environments [1].

- Limitations: The primary limitations of standard PMMA POFs are their high optical attenuation (limiting use to short-range applications) and lower bandwidth compared to silica fibers [1] [2]. However, perfluorinated GI-POFs like CYTOP have significantly improved performance in both bandwidth and attenuation [3] [2].

Biocompatibility and Biomedical Advantages

The intrinsic material properties of certain polymers make POFs exceptionally suitable for biomedical applications. Biocompatibility refers to the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application, and several POF materials meet this requirement [3].

Inherent Biocompatibility of Polymer Materials

Many polymers used in POFs are known for their biocompatibility. PMMA is a widely used biomaterial. More importantly, several synthetic polymers—including poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)—have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical applications [3]. These materials are not only biocompatible but also offer biodegradability, meaning they can be hydrolyzed or degraded into small, metabolizable molecules in a physiological environment, thus avoiding the need for surgical removal after implantation [3].

Advantages Over Silica Fibers in Medical Settings

The mechanical properties of POFs provide decisive advantages over silica fibers for in-vivo and wearable applications.

- Flexibility and Safety: POFs have a lower Young's modulus (~3.2 GPa for PMMA) and a higher failure strain than silica fibers, making them highly flexible and less prone to breakage inside the body, which minimizes the risk of tissue damage [3].

- Reduced Inflammatory Response: The mechanical and chemical properties of silica fibers can lead to issues like chronic inflammation and tissue damage when implanted. The more tissue-like flexibility and proven biocompatibility of certain polymer fibers help mitigate these adverse body reactions [3].

- Functionalization for Enhanced Biocompatibility: Research is exploring materials like hydrogels for optical fibers. Hydrogels have high water content that mimics the extracellular matrix, improving compatibility and softening the fiber-tissue interface [3].

Table 2: Overview of Biocompatible and Biodegradable Polymer Materials for POFs

| Material Category | Example Materials | Key Properties | Potential Biomedical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Polymers (FDA-Approved) | PLA, PGA, PLGA, PEG [3] | Biodegradable, biocompatible, tunable degradation rates [3] | Biosensing, drug delivery, tissue engineering, temporary implants [3] |

| Natural Materials | Silk, cellulose, agarose, proteins [3] | Superior biocompatibility, intrinsic biodegradability, nontoxicity [3] | Bio-integrated sensors, transient medical devices [3] |

| Hydrogels | Poly(ethylene glycol)-based, alginate-based [3] | High water content, tissue-like softness, self-healing properties, porous structure [3] | Mitigating tissue damage at the implant interface, soft robotics sensing [3] |

| Elastomers | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | High stretchability, flexibility | Wearable sensors, stretchable photonics |

Application Notes for Biomechanics Research

The combination of flexible, biocompatible, and sensing-capable POFs opens up significant opportunities in biomechanics research, which quantifies motion, forces, and control strategies to understand performance and injury [5].

Application 1: Human Motion and Gait Analysis

Objective: To quantitatively assess joint angles, spatiotemporal gait parameters, and muscle activity in real-world environments using wearable POF sensors. Background: Biomechanical analysis of human movement is essential for diagnosing movement disorders, optimizing athletic performance, and guiding rehabilitation [5]. Traditional motion capture systems are often limited to lab settings. POF sensors, particularly those based on fiber Bragg gratings (FBGs), can be integrated into textiles or flexible patches to create wearable, unobtrusive monitoring systems [1]. Protocol:

- Sensor Fabrication: Inscribe FBG arrays in a single, biocompatible POF (e.g., a medical-grade CYTOP or biodegradable PLA fiber). The gratings act as wavelength-specific reflection points sensitive to strain and temperature.

- System Calibration: Calibrate the wavelength shift of each FBG against known strain and temperature values in a controlled environment to establish a baseline [6].

- Sensor Placement: Securely attach the POF-FBG sensor to the skin or integrate it into a elastic sleeve/garment targeting the joint of interest (e.g., knee, hip, wrist). Ensure minimal slippage during movement.

- Data Acquisition: Use a portable interrogator unit to send broadband light through the POF and record the reflected Bragg wavelengths from each grating in real-time during the subject's activity (e.g., walking, running, squatting).

- Data Processing: Convert the recorded wavelength shifts into strain measurements. Use biomechanical models to translate strain data from multiple FBGs along the fiber into joint angle kinematics.

Workflow for POF-based Human Motion Analysis

Application 2: Plantar Pressure Mapping

Objective: To measure and map the pressure distribution on the plantar surface of the foot during standing and locomotion. Background: Altered plantar pressure is linked to various pathologies such as diabetic foot ulcers, gait disorders, and hallux limitus [5] [1]. POF-based sensors are ideal for this application due to their high elastic strain limit, flexibility, and resistance to repeated mechanical loading [1]. Protocol:

- Sensor Grid Construction: Create a grid of multiple intensity-based or FBG-based POF sensors. For intensity-based systems, configure the fibers such that pressure applied at specific points modulates the intensity of transmitted light.

- Insole Integration: Embed the POF sensor grid into the layers of a flexible, insole-shaped substrate, ensuring the sensing points are positioned at key anatomical landmarks (e.g., heel, metatarsal heads, hallux).

- Signal Conditioning: Connect the POF insole to a signal conditioning unit containing LEDs (light source) and photodetectors. For intensity-based systems, implement reference channels to compensate for intensity fluctuations unrelated to pressure.

- Data Collection: Subjects wear the instrumented insoles inside their shoes. Data is collected while the subject stands still, walks on a treadmill, or moves freely, streamed wirelessly to a data logger.

- Analysis and Mapping: Correlate the signal loss (intensity-based) or wavelength shift (FBG-based) from each sensing point with calibrated pressure values. Use software to generate a dynamic, color-coded pressure map of the foot.

Application 3: Monitoring of Biomechanical Forces in Rehabilitation

Objective: To monitor the forces and movements applied by a patient during rehabilitation exercises, either with a therapist or using a robotic device, to ensure adherence and measure progress. Background: Biomechanical analysis drives the development of targeted, evidence-based rehabilitation, including the use of wearables and robotic aids with "assist-as-needed" control strategies [5]. POF sensors can be integrated into these systems as safe, EMI-immune force and movement transducers. Protocol:

- Sensor Integration: Embed POF strain sensors (e.g., FBGs) within the structural components of a rehabilitation robot, a smart splint, or a resistance band at locations of expected mechanical stress.

- Establish Baseline: For "assist-as-needed" robots [5], record the sensor data corresponding to correct exercise form performed under a therapist's guidance to establish a patient-specific baseline.

- Real-Time Monitoring: During unsupervised or assisted exercise sessions, continuously monitor the sensor output. In robotic systems, the sensor data can be fed into a control algorithm that dynamically adjusts the level of assistance provided [5].

- Feedback and Progression: Provide auditory, visual, or haptic feedback to the patient based on the sensor data to correct movement patterns. Use the collected data to objectively track the patient's recovery and progressively adjust the difficulty of the exercises.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for POF Sensing in Biomechanics

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible POF | PMMA, CYTOP, or biodegradable (PLA, PLGA) optical fibers serving as the sensing element and light guide. | Core material for all biomedical POF sensors; biodegradable fibers for transient implants. |

| Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) Inscription System | A laser-based system to inscribe periodic refractive index modulations (gratings) into the POF core. | Creating wavelength-specific sensing points in the fiber that are sensitive to strain and temperature. |

| Optical Interrogator | An instrument that emits light into the POF and precisely measures the spectrum of reflected (FBG) or transmitted light. | The main data acquisition unit for reading the sensor's output with high resolution. |

| Signal Conditioning Circuitry | Custom electronic circuits for amplifying and filtering the electrical signal from photodetectors. | Essential for improving the signal-to-noise ratio in intensity-based POF sensing systems. |

| Calibration Jigs | Mechanical fixtures (e.g., motorized translation stages, calibrated weights) for applying known strains or pressures to the POF sensor. | Used to establish the quantitative relationship between the measured optical signal and the physical parameter of interest. |

| Biocompatible Encapsulation | Medical-grade silicone, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), or hydrogel materials. | Protects the fiber, enhances mechanical coupling with tissue, and ensures biocompatibility for in-shoe or on-skin sensors. |

Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) sensing represents a transformative technology for biomechanics research, offering unique advantages for monitoring human movement and physiological signals. Unlike traditional silica fibers, POFs are characterized by their high flexibility, superior strain tolerance, and biocompatibility, making them ideally suited for integration into wearable devices and smart textiles [7] [8]. These sensors operate primarily on three distinct physical mechanisms: Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs), which detect shifts in reflected wavelength; intensity-based sensors, which measure changes in transmitted light power; and evanescent wave sensors, which exploit the interaction of light extending beyond the fiber core with the surrounding environment [7] [9] [10]. This document details the operating principles, applications, and experimental protocols for these key sensing mechanisms within the context of advanced biomechanics research.

Sensing Mechanisms and Performance Comparison

The following section delineates the fundamental principles and comparative performance of the three core sensing technologies.

Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs)

An FBG is a periodic modulation of the refractive index within the core of an optical fiber. It acts as a wavelength-specific mirror, reflecting a narrow band of light centered at the Bragg wavelength, λ_B, defined by λ_B = 2 * n_eff * Λ, where n_eff is the effective refractive index of the fiber core and Λ is the grating period [7]. When the fiber is subjected to mechanical strain (Δε) or temperature changes (ΔT), both n_eff and Λ are altered, leading to a measurable shift in the Bragg wavelength (Δλ_B) [7]. This relationship is the foundation for their use as precise quantitative sensors.

Intensity-Based Sensors

Intensity-modulated fiber optic sensors (IM-FOSs) represent a cost-effective and structurally simple alternative. Their operation relies on measuring variations in the intensity of light transmitted through or reflected from the fiber in response to an external stimulus [10]. These changes can be induced through several mechanisms, including:

- Macrobending: Light radiates out of the fiber due to bends exceeding a critical radius, causing power loss [10].

- Microbending: Small, periodic deformations of the fiber cause coupling of light from guided modes to radiation modes, attenuating the signal [10].

- Evanescent Field Coupling: In twisted-fiber configurations, pressure can frustrate total internal reflection, coupling light from an illuminating fiber to an adjacent receiving fiber, thus varying the measured intensity [9].

Evanescent Wave Sensors

During total internal reflection, a standing electromagnetic wave, known as an evanescent wave, is formed, with its intensity decaying exponentially with distance from the core-cladding interface [10]. The penetration depth (d_p) of this field determines its sensitivity to the surrounding medium. In POF sensors, this principle is harnessed by removing a portion of the cladding to enhance the interaction between the evanescent field and the external environment. Changes in the refractive index or the absorption characteristics of the surrounding medium (e.g., sweat on the skin) directly modulate the intensity or spectrum of the transmitted light, enabling biochemical sensing [11] [8].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key POF Sensing Mechanisms in Biomechanics

| Sensing Mechanism | Measurand | Typical Sensitivity (POF) | Key Advantages | Common Biomechanics Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) | Strain, Temperature | Tuneable via pre-strain [8] | Absolute wavelength encoding, Multiplexing capability, High accuracy | Kinematics analysis [12], Gait analysis [12], Respiration rate [12] |

| Intensity-Based (Macro/Microbending) | Pressure, Bending, Displacement | 432.21 nW/MPa (pressure) [9] | Simple, Low-cost, Robust | Smart textile integration [10], Breathing monitoring [12], Joint movement tracking [12] |

| Evanescent Wave | Refractive Index, Biochemical concentration | 2008.58 nm/RIU (in POF) [8] | Direct chemical/biomarker detection, Label-free | Sweat pH monitoring [12], Metabolite detection [11] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Optical Fiber Sensing Technologies

| Parameter | FBG Sensors | Intensity-Based Sensors | Evanescent Wave Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Wavelength shift [7] | Intensity variation [9] [10] | Evanescent field modulation [11] |

| Sensitivity | High (strain/temperature) [7] | Moderate [10] | Very High (refractive index) [8] |

| Multiplexing | Excellent [7] [13] | Good [10] | Challenging |

| Cost | High (interrogation) [7] | Low [9] [10] | Moderate |

| EMI Immunity | Excellent [7] [13] | Excellent [10] | Excellent |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for POF Sensor Development

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) | Sensing element; typically made of materials like CYTOP or PMMA [8]. | The core medium for all sensor types; chosen for flexibility and biocompatibility. |

| FBG Interrogator | Measures and tracks the wavelength shifts from FBGs with high precision. | Essential for decoding strain and temperature data from POFBG sensors. |

| Optical Power Meter (e.g., Thorlabs PM100USB) | Measures the intensity of light output from the fiber. | Used to quantify signal changes in intensity-based and evanescent wave sensors [9]. |

| LED Light Source (e.g., 660 nm M660F1) | Provides incoherent light for intensity-based systems. | A stable, low-cost light source for sensors where coherence is not required [9]. |

| Side-Polishing Setup | Creates a sensing window by selectively removing the fiber cladding. | Enables the development of evanescent wave and surface plasmon resonance sensors [8]. |

| pH-Sensitive Hydrogel | A functional coating that expands/contracts with pH changes. | Coated on FBGs or evanescent wave sensors for sweat pH monitoring [7] [12]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Fabrication of a POF-Based Intensity Sensor for Pressure Monitoring

This protocol outlines the creation of a simple, high-pressure sensor using a twisted POF structure, suitable for monitoring external pressure in biomechanical setups [9].

Workflow: Fabrication of a Twisted POF Intensity Sensor

Materials:

- Two 1-meter lengths of commercial POF (e.g., Mitsubishi SK-40, core diameter ~980 µm) [9].

- LED light source (e.g., Thorlabs M660F1, 660 nm).

- Optical power meter (e.g., Thorlabs PM100USB with S151C photodetector).

- Mechanical setup for applying and controlling pressure.

- Silicone gel for sealing.

Procedure:

- Fiber Preparation: Cut two POFs to the desired length. Ensure end-faces are clean and properly cleaved for efficient light coupling.

- Sensor Fabrication: Select and create one of the following sensing structures in a designated section (e.g., between 49.5 cm and 50.5 cm) of the two POFs [9]:

- Twisted Configuration: Twist the two POFs together firmly for a defined number of turns.

- Twisted-Bend Configuration: After twisting, introduce a specific bend radius to the twisted section. This configuration typically offers higher sensitivity.

- Twisted-Helical Configuration: Form the twisted section into a helical coil. This configuration is known to enhance the sensing range.

- Integration: Protect the sensing region from ambient light using a black tube or by placing it within a dark pressure chamber. Use silicone gel to seal the chamber and prevent leakage while allowing pressure transmission.

- Optical Setup: Launch light from the LED source into the core of the first ("illuminating") POF. Connect the second ("receiving") POF to the optical power meter.

- Calibration and Measurement: Apply known pressures to the sensing region. Record the corresponding output from the optical power meter. As pressure increases, frustrated total internal reflection will cause a variation in the coupled intensity. Plot power output versus applied pressure to establish a calibration curve. The twisted-bend structure has demonstrated a sensitivity of approximately 432.21 nW/MPa [9].

Protocol: Functionalization of an Evanescent Wave POF Sensor for Sweat pH Monitoring

This protocol describes the development of a wearable sweat sensor by functionalizing a side-polished POF with a pH-responsive material [12] [8].

Workflow: Functionalization of a POF pH Sensor

Materials:

- Side-polished or etched POF.

- pH-sensitive hydrogel (e.g., poly(acrylic acid) or similar copolymer).

- Refractometer for system validation.

- Spectrometer or optical power meter for signal acquisition.

- Buffer solutions of known pH for calibration.

Procedure:

- Fiber Preparation: Create a sensing window on the POF using a side-polishing technique or chemical etching with a suitable agent like hydrofluoric acid. This process exposes the evanescent field to the external environment [7] [8].

- Sensor Functionalization: Apply a thin, uniform layer of the pH-sensitive hydrogel onto the exposed sensing window. The gel should adhere firmly to the fiber surface. Allow it to cure under controlled conditions.

- Integration: Embed the functionalized fiber into a wearable platform, such as a sweat-absorbent textile or a wristband, ensuring the sensing window is in direct contact with the skin or the collected sweat.

- Measurement and Data Acquisition:

- Connect one end of the POF to a broadband light source and the other to a spectrometer.

- As sweat contacts the hydrogel, the gel expands or contracts in response to pH changes, inducing mechanical stress on the fiber and modulating the evanescent field. This causes a shift in the transmission spectrum or a change in output intensity [7] [12].

- Calibrate the sensor by exposing it to standard buffer solutions and recording the spectral or intensity response. The subsequent measurement of an unknown sweat sample can then be correlated to its pH value.

Protocol: Multiplexed POFBG Sensor Array for Kinematic Analysis

This protocol covers the use of multiple POFBGs written into a single fiber to measure strain at different locations simultaneously, ideal for analyzing complex body movements [12] [8].

Workflow: Multiplexed POFBG Sensor System

Materials:

- Single-mode or few-mode POF suitable for FBG inscription (e.g., CYTOP).

- Femtosecond laser or UV laser system with phase mask for grating inscription [7].

- FBG interrogator.

- Elastic textile substrate (e.g., a sleeve or legging).

Procedure:

- Grating Inscription: Use a phase mask technique or a point-by-point femtosecond laser writing method to inscribe multiple FBGs at predefined locations along the POF. Each FBG is designed to reflect a unique Bragg wavelength at a reference state [7].

- Sensor Conditioning: Apply a specific pre-strain to the POF during integration. This pre-strain can be used to selectively tune the temperature and humidity sensitivity of the sensors, which is crucial for minimizing cross-sensitivity in biomechanical applications [8]. Perform thermal annealing to improve the stability and repeatability of the POFBGs.

- Textile Integration: Carefully embed the POFBG array into the smart textile garment, aligning each FBG with a specific anatomical landmark (e.g., over a joint like the knee or elbow). The fiber should be secured in a way that ensures strain is effectively transferred from the textile to the fiber during movement.

- Data Collection: Connect the POFBG array to an interrogator. As the body moves, the strain at each joint causes a proportional shift in the Bragg wavelength of the corresponding FBG. The interrogator tracks all wavelength shifts in real-time, demultiplexing the signals to provide synchronized, multi-point strain data for comprehensive kinematic analysis [12].

Polymer Optical Fibers (POFs) are increasingly becoming the material of choice in biomechanics research, particularly for applications requiring direct interaction with the human body. Their emergence addresses critical limitations posed by traditional Silica Optical Fibers (SOFs), especially in wearable sensing and robotic instrumentation. This document outlines the core mechanical advantages of POFs—specifically their superior flexibility, fracture toughness, and impact resistance—and provides a comparative analysis with silica fibers. Supported by quantitative data and detailed experimental protocols, this application note serves as a guide for researchers and scientists seeking to leverage POFs for robust, high-fidelity, and safe biomechanical sensing.

Comparative Analysis: POFs vs. Silica Fibers

The selection between POFs and SOFs is pivotal to the design and performance of a biomechanical sensor. The table below summarizes the key comparative advantages of POFs based on their material properties.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Polymer and Silica Optical Fibers for Biomechanics

| Property | Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) | Silica Optical Fiber (SOF) | Implication for Biomechanics Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexibility | High flexibility; lower Young's modulus (≈2-3 GPa) [14] [15] | Higher Young's modulus (≈70 GPa); more rigid [16] | Enables integration into soft, compliant textiles and wearable structures without hindering movement [14] [12]. |

| Fracture Toughness | High fracture toughness; high elastic strain limits [14] [15] | Brittle; prone to catastrophic failure [16] | Withstands repeated large strains and deformations in wearable robots and smart textiles, ensuring sensor longevity [14]. |

| Impact Resistance | High impact resistance; can withstand mechanical shock [14] [17] | Brittle; can break upon impact, risking glass punctures [14] | Essential for patient safety; eliminates risk of injury from broken fibers in wearable applications [14]. |

| Elongation at Break | Can exceed 10% strain before failure [15] [18] | Typically less than 1% strain before failure [16] | Allows for measurement of large deformations and is suitable for sensing in joints and muscles [14]. |

| Ease of Handling & Installation | Easy to cut, terminate, and install; low cost [16] | Requires specialized tools and trained professionals for installation [16] | Facilitates rapid prototyping and deployment of sensor systems, reducing development time and cost [16]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core material properties of POFs and the resulting benefits for biomechanics applications.

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing POF Properties

To validate POF performance for specific biomechanics applications, standardized experimental characterization is essential. Below are detailed protocols for key mechanical tests.

Protocol: Large-Strain Tensile Testing for Sensor Validation

This protocol is used to characterize the elastic strain limit and tensile performance of a single-mode POF, which is critical for sensors intended to measure large deformations [15].

- Objective: To calibrate the phase shift as a function of applied displacement in a single-mode POF interferometer and validate its performance for large-strain measurements up to 10% nominal elongation [15].

- Materials and Equipment:

- Single-mode Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) POF

- Mach-Zehnder interferometer setup

- Motorized translation stage with force sensor

- Laser light source (632.8 nm wavelength)

- Photodetector and data acquisition system [15]

- Procedure:

- Step 1: Assemble the Mach-Zehnder interferometer, integrating the POF as the sensing arm.

- Step 2: Fix both ends of the POF sample to the translation stage, ensuring a known gauge length.

- Step 3: Apply a controlled displacement at a constant strain rate using the translation stage.

- Step 4: Simultaneously record the applied displacement/force from the translation stage and the corresponding phase shift from the interferometer's output.

- Step 5: Continue the test until fiber failure or the target strain (e.g., 10%) is reached.

- Step 6: Analyze the data to establish a calibration curve of phase shift versus applied strain [15].

- Expected Outcome: A linear relationship between phase shift and applied strain, confirming the POF's suitability for high-precision, large-strain sensing applications.

Protocol: Impact Resistance of Composite-Integrated POFs

This protocol assesses the enhancement of impact resistance when POFs are embedded into composite materials, simulating conditions in protective gear or exoskeletons [17].

- Objective: To evaluate the dynamic impact resistance of a 3D-printed continuous optical fiber-reinforced helicoidal Polylactic Acid (PLA) composite (COF-HP) using a Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) [17].

- Materials and Equipment:

- Self-developed multi-material continuous fiber 3D printer

- Polylactic Acid (PLA) filament

- Continuous Optical Fiber (COF)

- Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) apparatus

- High-speed camera

- Digital Image Correlation (DIC) software [17]

- Procedure:

- Step 1: Fabricate Specimens: Use the 3D printer to manufacture cylindrical COF-HP specimens with a defined helicoidal structure (e.g., 60° spiral angle). Control the printing path via modified G-CODE.

- Step 2: Compact Specimens (Optional): To reduce porosity, place printed specimens in a ring mold and heat in an oven at 70–80 °C. Apply a quasi-static compressive load to compact the specimen to a predefined height.

- Step 3: Perform Impact Test: Place the specimen between the incident and transmission bars of the SHPB. Subject the specimen to impact loading at high strain rates (e.g., 680 s⁻¹ and 890 s⁻¹).

- Step 4: Data Collection: Use strain gauges on the SHPB bars to record stress-strain data. Simultaneously, capture the deformation process using a high-speed camera.

- Step 5: Data Analysis: Analyze the stress-strain and energy absorption curves. Use DIC software to process high-speed footage for full-field strain distribution and damage evolution [17].

- Expected Outcome: The COF-reinforced specimens will exhibit higher maximum stress and improved energy absorption compared to pure PLA structures, demonstrating enhanced impact resistance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for POF Sensor Development in Biomechanics

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research & Development | Exemplar Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Single-mode PMMA POF | Core sensing element for high-precision, large-strain measurements in interferometric setups [15]. | Core diameter: ~1-100 µm; Cladding: Fluorinated polymer [19]. |

| Multimode PMMA POF | Used for intensity-based sensing, often in wearable textiles for monitoring parameters like breathing or gait [14] [12]. | Core diameter: 486 µm; Cladding diameter: 500 µm; NA: High [19]. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | A common thermoplastic polymer used as a matrix for embedding and integrating POFs into 3D-printed structures and composites [17]. | Processing Temperature: 195-230 °C [17]. |

| Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) | A transparent conductive oxide used as an overlayer on POF-based Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) sensors to significantly enhance refractive index sensitivity [19]. | Optimal thickness: ~25 nm; Coated over a 40 nm Gold film [19]. |

| Gold (Au) Sputtering Target | Used to coat POFs to create a metal layer for exciting surface plasmons in SPR-based biosensors [19]. | High purity (99.99%); Thickness: 40-60 nm [19]. |

The distinct material properties of Polymer Optical Fibers—notably their high flexibility, fracture toughness, and impact resistance—make them uniquely suited for the demanding environment of biomechanics research. Their ability to undergo large strains, resist mechanical shock, and be safely integrated into wearable systems provides a significant advantage over traditional silica fibers. By following the standardized experimental protocols outlined in this document, researchers can reliably characterize these properties and develop next-generation sensing solutions for healthcare monitoring, rehabilitation robotics, and human movement analysis.

Electromagnetic Immunity and Safety Considerations for Biomedical Applications

The increasing integration of electronic systems and wireless technologies into healthcare has made electromagnetic interference (EMI) a critical challenge for biomedical device safety and reliability [20]. EMI can disrupt the normal operation of electronic devices, posing significant risks in biomedical applications where patient safety depends on accurate physiological monitoring and device functionality [20]. For polymer optical fiber (POF) sensors used in biomechanics research, understanding and addressing electromagnetic immunity is paramount for ensuring data integrity and patient safety in both clinical and research environments.

This application note examines the fundamental principles of electromagnetic immunity specific to POF sensing systems, provides validated experimental protocols for assessing EMI resistance, and outlines a comprehensive safety framework for deploying these sensors in electromagnetically complex healthcare settings. The content is specifically contextualized within a broader thesis on polymer optical fiber sensing in biomechanics research, addressing the unique requirements of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of medical sensing and electromagnetic compatibility.

Electromagnetic Interference in Biomedical Environments

Electromagnetic interference in healthcare settings originates from diverse sources including wireless communication systems, power lines, industrial equipment, and the medical devices themselves [20]. The proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, 5G technologies, and smart medical systems has significantly increased the complexity of the electromagnetic environment in clinical and research settings [20].

The consequences of EMI in biomedical applications are particularly severe. Active medical implants such as pacemakers, defibrillators, and insulin pumps can experience compromised functionality, creating direct threats to patient safety [20]. In research settings, EMI can corrupt sensitive physiological data collected during biomechanical studies, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions and compromised research outcomes. The healthcare sector consequently requires exceptionally high standards for electromagnetic compatibility, with specific regulatory requirements governing device immunity.

Shielding Effectiveness Metrics and Standards

Shielding effectiveness (SE) is the primary metric for evaluating EMI protection, defined as the logarithmic ratio of incident to transmitted electromagnetic power expressed in decibels (dB) [20]. The required level of shielding varies significantly based on the application and device criticality.

Table 1: Shielding Effectiveness Standards for Different Applications

| Application Context | Typical SE Requirement | Attenuation Level | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Electronics | 40-60 dB | 99.99-99.999% | Consumer device reliability |

| Industrial/Medical Equipment | 60-80 dB | 99.9999% | Patient-connected devices |

| Critical Medical/Military | 80-100+ dB | >99.99999% | Life-support systems |

| Polymer Optical Fiber Sensors | Inherent immunity | N/A | No conductive path for interference |

For conventional electronic medical devices, shielding materials must provide adequate protection across relevant frequency ranges. Traditional metallic shielding materials (copper, aluminum, nickel) offer high conductivity but present limitations including high density, corrosion susceptibility, and processing difficulties [20] [21]. Advanced polymer composites with carbon-based nanomaterials (graphene, carbon nanotubes, carbon foams) have emerged as promising alternatives, offering exceptional electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and environmental sustainability while addressing weight and flexibility requirements [20] [21].

Electromagnetic Immunity of Polymer Optical Fiber Sensors

Fundamental Immunity Mechanisms

Polymer optical fiber sensors offer inherent electromagnetic immunity because they operate on optical rather than electronic principles [22]. Unlike conventional electronic sensors that rely on electrical currents through conductive paths susceptible to electromagnetic induction, POF sensors use light propagation through dielectric waveguide structures [22]. This fundamental operating principle provides natural resistance to electromagnetic interference, making them particularly valuable for biomechanics research in high-EMI environments.

The non-conductive nature of optical fibers means they do not act as antennas for electromagnetic waves and are unaffected by electromagnetic induction effects that plague electronic sensors [22]. This immunity extends across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from extremely low frequencies to radio and microwave frequencies, ensuring reliable operation in diverse electromagnetic environments encountered in healthcare settings [22].

Comparative Advantages in Biomechanics Research

In biomechanics research applications, POF sensors provide significant advantages for monitoring physiological parameters in challenging electromagnetic environments:

- Patient Safety: Electrical isolation eliminates risk of electrical shock when monitoring human subjects [22]

- Signal Integrity: Immunity to EMI ensures accurate data collection during movement analysis in environments with wireless equipment [22]

- Miniaturization Potential: Small diameter fibers enable integration into wearable biomechanics monitoring systems without compromising immunity [22]

- Multiparameter Sensing: Capability to simultaneously monitor multiple physical parameters (pressure, temperature, strain) without cross-talk [22]

Table 2: POF Sensor Applications in Biomedical Monitoring

| Biomechanical Parameter | POF Sensing Mechanism | Research/Clinical Application | EMI Immunity Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure | Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBG) | Intracranial pressure monitoring | Critical in MRI environments |

| Temperature | Fabry-Pérot interferometry | Metabolic monitoring during activity | Unaffected by diathermy equipment |

| Strain | Intensity-based or FBG | Joint movement analysis | Reliable near electrosurgical units |

| Biochemical | Surface Plasmon Resonance | Metabolite detection in sweat | Immune to wireless telemetry interference |

Experimental Protocols for EMI Validation

EMI Immunity Testing for POF Sensing Systems

Objective: This protocol validates the electromagnetic immunity of polymer optical fiber sensors and their readout systems when subjected to standardized EMI exposure, simulating realistic healthcare environments.

Principle: POF sensors theoretically possess inherent EMI immunity, but complete sensing systems including optoelectronics, interconnections, and signal processing components may exhibit vulnerabilities. This test characterizes system-level performance under controlled EMI conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer optical fiber sensors (750 μm diameter, refractive index 1.49 recommended) [23]

- Optical signal conditioning unit (interrogator) with digital output

- EMI test chamber meeting IEC 61000-4-3 standards

- Reference sensors for baseline measurement

- Signal recording system with time-synchronization capability

- Temperature and humidity monitoring equipment

Procedure:

- Baseline Establishment:

- Calibrate the POF sensor against reference standards under zero-EMI conditions

- Characterize normal performance parameters including sensitivity, linearity, and noise floor

- Record baseline data for a minimum of 30 minutes to establish statistical significance

EMI Exposure Regimen:

- Position the POF sensor system in the EMI test chamber according to standardized geometry

- Expose the system to standardized field strengths (1 V/m to 30 V/m) across frequency ranges (0-300 GHz)

- Focus particularly on medical and communication bands (400 MHz, 900 MHz, 1.8 GHz, 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz)

- Maintain each test condition for sufficient duration to detect slow-response interference

Data Collection:

- Continuously monitor sensor output throughout exposure cycles

- Record signal stability, signal-to-noise ratio, and measurement accuracy

- Document any transient responses during EMI field activation/deactivation

Performance Analysis:

- Compare sensor performance during EMI exposure to baseline measurements

- Quantify any EMI-induced deviations as percentage of measurement range

- Classify immunity according to medical device standards (typically <1% deviation acceptable)

Validation Criteria: Successful validation requires maintaining specified measurement accuracy (typically ±1% of full scale) throughout all EMI exposure conditions without protective shielding.

Shielding Effectiveness Measurement for Composite Materials

Objective: This protocol determines the shielding effectiveness of polymer composite materials intended for EMI protection of non-optical components in POF sensing systems.

Principle: Shielding effectiveness is quantified by measuring the attenuation of electromagnetic waves passing through a material, using vector network analyzers to determine transmission and reflection coefficients.

Materials and Equipment:

- Sample polymer composite materials (minimum 100×100 mm)

- Vector network analyzer (VNA) with frequency capability to 8 GHz

- Waveguide or coaxial sample holders appropriate for material dimensions

- Calibration standards for VNA

- Sample preparation equipment (cutting tools, thickness gauges)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Cut material samples to precise dimensions required by test fixture

- Measure and record sample thickness at multiple points

- Condition samples at standard temperature and humidity (23°C, 50% RH) for 24 hours

System Calibration:

- Calibrate VNA using appropriate calibration standard (SOLT, TRL)

- Verify calibration accuracy with known reference materials

- Establish baseline without sample to characterize test fixture

Measurement:

- Position sample in test fixture ensuring proper electrical contact

- Measure S-parameters (S11, S12, S21, S22) across frequency range of interest

- Repeat measurements at multiple sample orientations if material anisotropy is suspected

Calculation:

- Calculate shielding effectiveness from S-parameters using standard formulas:

- SE = -20log₁₀|S₂₁| dB

- Determine contributions from reflection (SER) and absorption (SEA)

- Calculate absolute effectiveness based on application requirements

- Calculate shielding effectiveness from S-parameters using standard formulas:

Validation Criteria: Materials intended for medical device shielding should demonstrate minimum 40 dB shielding effectiveness across relevant frequency ranges, with consistent performance across multiple samples.

Safety Implementation Framework

Risk Assessment Protocol

A systematic risk assessment approach ensures comprehensive identification and mitigation of EMI-related hazards in biomedical sensing applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for EMI-Immune Biomedical Sensing Research

| Material/Component | Function | Application Notes | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Optical Fibers (750 μm) | Signal transmission with inherent EMI immunity | Core sensing element; select based on numerical aperture and mechanical properties | PMMA-based optical fibers with 1.49 refractive index [23] |

| Carbon-Based Nanocomposites | EMI shielding for electronic components | Applied to non-optical system elements; graphene and CNT composites offer high SE with flexibility | Graphene-epoxy composites achieving 40-60 dB SE [20] |

| Cerium Dioxide (CeO₂) Nanoparticles | Sensing layer enhancement | Green-synthesized nanoparticles improve refractive index for enhanced sensitivity [23] | Oak fruit extract-synthesized CeO₂ for LMR sensors [23] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Selective analyte recognition | Creates synthetic recognition sites; compatible with optical fiber functionalization | Polystyrene MIP for tamoxifen detection [23] |

| Conductive Polymer Matrices | Hybrid shielding materials | Combine polymer flexibility with controlled conductivity; PEDOT:PSS for transparent shields | Polyimide substrates with metal coatings (40-60 dB SE) [20] |

| Fiber Interrogation Systems | Optical signal processing | Convert optical signals to digital data; potential EMI vulnerability point requires assessment | FBG interrogators with 1 pm wavelength resolution |

Polymer optical fiber sensors represent a robust solution for biomedical sensing applications in electromagnetically challenging environments. Their inherent immunity to electromagnetic interference, combined with appropriate shielding strategies for auxiliary components, provides a reliable foundation for biomechanics research and clinical monitoring. The experimental protocols and safety framework presented in this application note offer researchers and medical device developers standardized methodologies for validating electromagnetic compatibility and ensuring patient safety. As biomedical sensing technologies continue to evolve alongside increasingly dense electromagnetic environments, the fundamental advantages of optical sensing modalities will become increasingly critical for ensuring measurement integrity and patient safety.

Core Principles of Biomechanical Monitoring with POF Technology

Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) sensing technology has emerged as a powerful tool for biomechanical monitoring, offering unique advantages for quantifying human movement and physiological parameters. POF sensors function based on the modulation of light properties—such as intensity, wavelength, or phase—within an optical fiber when subjected to external mechanical deformations like bending, stretching, or pressure. These physical changes alter the transmission characteristics of light through the fiber, which can be precisely measured and correlated with specific biomechanical parameters. The fundamental principle enabling this technology is the interaction between external mechanical stimuli and the guided light within the fiber, which forms the basis for monitoring kinematic and kinetic parameters during human movement.

The core advantages of POF sensors over conventional electronic alternatives include their inherent immunity to electromagnetic interference, which ensures stable operation in environments with electrical noise; biocompatibility and safety for human wear; and high flexibility that allows integration into textiles and wearable devices without restricting natural movement. Furthermore, POF sensors demonstrate multiplexing capabilities, enabling multiple sensing points along a single fiber, and possess material properties including lower Young's modulus and higher fracture toughness compared to silica fibers, making them particularly suitable for applications involving large strains and dynamic movements.

Fundamental Operating Principles

POF sensors for biomechanical monitoring primarily operate on two fundamental principles: intensity modulation and wavelength shift mechanisms. Intensity-based sensors function by measuring changes in the power of light transmitted through the fiber when subjected to mechanical deformation. This is frequently achieved through macro-bend configurations, where bending the fiber causes light to escape from the core, resulting in measurable attenuation. The relationship between bend radius and optical power loss provides a quantitative measurement of movement or applied force. For sensors based on lateral sections, the sensitive zone is created by removing part of the fiber cladding and core, which increases sensitivity to bending through enhanced radiation losses and surface scattering effects [24].

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors represent a more sophisticated approach based on wavelength modulation. FBGs are periodic structures inscribed in the fiber core that reflect a specific wavelength of light while transmitting others. When the grating undergoes strain or temperature changes, the reflected wavelength shifts proportionally, enabling precise measurement. The fundamental relationship is governed by the Bragg condition: λBragg = 2nΛ, where λBragg is the Bragg wavelength, n is the effective refractive index, and Λ is the grating period. External mechanical strain alters both the grating period and the refractive index through the photoelastic effect, resulting in a measurable wavelength shift [25].

Table 1: Comparison of POF Sensing Principles for Biomechanical Monitoring

| Sensing Principle | Measured Parameter | Typical Applications | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity Modulation | Optical power loss | Gait analysis, joint angle, plantar pressure | 108.03 ± 100 mV/mm (lateral section sensors) [24] | Simple signal processing, low-cost implementation, high flexibility | Susceptible to power fluctuations, requires referencing |

| Macro-bend Sensing | Bend-induced attenuation | Plantar pressure, activity recognition | Dependent on bend radius (1-3 cm typical) [26] | Robust design, easy implementation, high dynamic range | Non-linear response at small bend radii |

| Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) | Wavelength shift | Muscle force, precise joint kinematics, temperature compensation | ~1.2 pm/με (strain), ~10 pm/°C (temperature) [25] | Absolute measurement, multiplexing capability, immunity to power fluctuations | Higher cost, complex interrogation, temperature cross-sensitivity |

Key Application Areas in Biomechanics

Lower Limb Biomechanics and Gait Analysis

The "POF Smart Pants" represent a significant advancement in lower limb monitoring, incorporating 60 intensity-based POF sensors (30 per leg) distributed across the lower extremities. This system employs multiplexed intensity variation technique with side coupling between POFs and modulated light sources. Each sensor exhibits sensitivity of 108.03 ± 100 mV/mm, normalized during data processing. The system can accurately classify various daily activities with 100% accuracy using neural networks, and through principal component analysis, the sensor count can be optimized threefold while maintaining 99% accuracy. This technology enables comprehensive assessment of lower limb biomechanics across different movement velocities and activities, providing spatiotemporal gait parameters essential for clinical diagnosis and sports performance monitoring [24].

Plantar Pressure Monitoring

Plantar pressure measurement systems utilizing POF technology employ macro-bend sensors integrated into insoles to monitor pressure distribution during gait. These sensors typically use conventional step-index PMMA fibers with 980μm core diameter and 2mm total diameter. Sensing elements are configured as loops with outer diameters of 1-3 cm, positioned parallel to the insole surface without requiring encapsulation. When load is applied, deformation occurs at the intersection points, causing fiber bending and consequent optical power attenuation through combined bend loss and stress-optic effects. The sensors demonstrate capability for both static and dynamic measurements, with the 1cm diameter sensor providing optimal spatial resolution for plantar pressure assessment. Validation against force platforms and commercial sensors confirms their accuracy in measuring vertical ground reaction forces during gait cycles [26].

Physiological Parameter Monitoring

POF sensors extend beyond biomechanical monitoring to encompass physiological parameter assessment, including respiration, heart rate, and body temperature. Specialized approaches incorporate chalcogenide fibers for simultaneous infrared-temperature dual sensing, enabling non-invasive monitoring of surface physiological evolution. Additionally, POF-based sensors have been developed for real-time sweat analysis, monitoring parameters such as pH levels through hydrogel optical fibers. These systems leverage the optical properties of specialized fiber materials that respond to biochemical changes in sweat composition, providing comprehensive physiological profiling during physical activity [27].

Table 2: Technical Specifications of POF Sensors in Biomechanical Applications

| Application Domain | Sensor Type | Key Performance Metrics | Measurement Range | Accuracy/Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limb Kinematics [24] | Multiplexed intensity-based POF | 60 sensors (30 per leg) | Full range of lower limb motion | Activity recognition: 100% (60 sensors), 99% (optimized 20 sensors) |

| Plantar Pressure Monitoring [26] | Macro-bend POF | 1-3 cm loop diameters | Ground reaction forces during gait | Comparable to force platforms and commercial sensors |

| Respiratory Monitoring [27] | Intensity-variation POF | Chest expansion measurement | Normal respiratory rates | Sufficient for clinical breath rate monitoring |

| Cardiac Monitoring [27] | FBG-based POF | Heart rate detection | Resting and exercise heart rates | Clinical-grade accuracy |

| Multi-parameter Sensing [27] | Chalcogenide fiber | Temperature + biochemical sensing | Physiological ranges | Real-time monitoring capability |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for POF Smart Pants Development and Validation

Objective: To develop and validate a smart textile system with integrated POF sensors for lower limb biomechanical monitoring and activity recognition.

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) optical fibers (1 mm diameter)

- Light emitting diodes (LEDs) for lateral coupling

- Photodetectors for signal acquisition

- Signal conditioning and data acquisition system

- Textile pants substrate for sensor integration

- Reference motion capture system (optional, for validation)

Fabrication Procedure:

- Fiber Preparation: Cut PMMA optical fibers to required lengths using a razor blade. Strip approximately 5mm of outer jacket from each end using a wire stripper to facilitate proper connection.

- Sensitive Zone Creation: Create lateral sections on the POF by removing cladding and part of the core at predetermined sensor locations. The section length (c) and depth (p) should be controlled for consistent sensitivity.

- Sensor Integration: Integrate two POFs with 30 sensors each into the pants textile, placing them strategically on left and right legs to capture key kinematic information. Ensure full integration without compromising textile flexibility.

- System Assembly: Connect LEDs for lateral coupling to the sensitive zones and photodetectors at fiber ends. Implement aluminum foil at end facets to increase signal reflection where necessary.

- Electronic Integration: Develop a portable signal acquisition unit placed inside the pants pocket, containing light sources, detectors, and data processing capabilities.

Calibration and Testing:

- Sensor Characterization: Characterize each of the 60 optical fiber sensors by applying transverse displacements to sensitive regions and recording output signals. Calculate individual sensitivities (typically 108.03 ± 100 mV/mm).

- Signal Normalization: Apply sensitivity values to normalize sensor responses prior to data analysis.

- Activity Protocol: Conduct tests with volunteers performing different daily activities (walking, sitting, standing, stair ascent/descent) while recording sensor data.

- Algorithm Development: Implement neural network algorithms for activity recognition, training on acquired dataset.

- Sensor Optimization: Apply principal component analysis to determine the minimal sensor count required for maintaining classification accuracy.

Validation Metrics:

- Activity recognition accuracy (target: >99%)

- Spatiotemporal gait parameter extraction

- System robustness during dynamic movements

- Comparison with reference systems (when available) [24]

Protocol for Plantar Pressure Insole Development

Objective: To design, fabricate, and characterize macro-bend POF sensors integrated into insoles for plantar pressure monitoring during gait.

Materials and Equipment:

- HFBR-R/EXXYYYZ step-index POF (PMMA core, 980μm diameter, 2mm total diameter)

- LED IF-E99B (650nm center wavelength) light source

- Photodetector circuit

- Ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) or polypropylene (PP) insole material (17mm heel, 2mm forefoot thickness)

- Universal testing machine for dynamic characterization

- Force platform for validation

Fabrication Procedure:

- Fiber Preparation: Cut POF to insole perimeter length using a razor blade. Strip 5mm of outer jacket from both ends with a wire stripper.

- Sensing Element Fabrication: Form loops with circular shapes of 1cm, 2cm, and 3cm outer diameters at strategic locations corresponding to high-pressure plantar areas (heel, metatarsal heads).

- Insole Integration: Embed the sensor loops within the insole material, ensuring they remain parallel to the insole surface without requiring encapsulation.

- Optical Connection: Connect the prepared POF to the LED light source and photodetector circuit, ensuring proper alignment and fixation.

Characterization and Testing:

- Static Load Testing: Apply known weights to the sensor regions and record optical power output to establish force-attenuation relationships.

- Dynamic Testing: Use a universal testing machine to apply sinusoidal loads at frequencies corresponding to walking and running activities.

- Gait Analysis: Recruit human subjects to walk with the instrumented insoles while collecting data synchronized with force platform measurements.

- Signal Processing: Implement algorithms to convert optical power attenuation to pressure values, accounting for sensor-specific calibration factors.

Validation Approach:

- Compare POF sensor outputs with simultaneous force platform measurements

- Evaluate sensor response at different gait velocities

- Assess reliability across multiple gait cycles [26]

Diagram 1: Workflow for POF Sensor Development and Implementation in Biomechanical Monitoring

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for POF Biomechanical Sensing Research

| Item | Specifications | Function/Role | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMMA Optical Fiber [24] [26] | Core diameter: 980μm-1mm, Cladding: 10μm fluorinated polymer | Primary sensing element; light guidance with modifiable transmission | Lower limb monitoring, plantar pressure sensing |

| Electrospinning Setup [28] | High-voltage source, polymer solution, collector | Fabrication of polymer nanofiber substrates for enhanced sensitivity | Specialized sensor coatings, flexible substrates |

| LED Light Sources [24] [26] | IF-E99B (650nm center wavelength) | Optical signal generation for intensity-based sensing | Lateral coupling in multiplexed systems |

| Photodetector Circuit [24] [26] | Photodiodes with signal conditioning | Conversion of optical signals to electrical measurements | Signal acquisition in wearable monitoring systems |

| FBG Interrogator [25] | High-resolution wavelength detection (~1pm) | Precise measurement of Bragg wavelength shifts | High-accuracy strain and temperature monitoring |

| Chalcogenide Fibers [27] | Infrared-transparent composition | Biochemical and thermal sensing through IR spectroscopy | Sweat analysis, multi-parameter physiological monitoring |

| Signal Processing Unit [24] | Portable microcontroller with data storage | Real-time signal processing and data management | Wearable system integration for remote monitoring |

Diagram 2: Signal Transduction Pathways in POF Biomechanical Sensors

Polymer Optical Fiber technology represents a transformative approach to biomechanical monitoring, offering unique advantages for wearable sensing applications. The core principles of operation—centered on light modulation in response to mechanical stimuli—enable precise measurement of kinematic and kinetic parameters during human movement. As research advances, POF sensors continue to evolve toward higher sensitivity, better integration with textiles, and enhanced multiplexing capabilities. The experimental protocols and technical specifications outlined in this document provide researchers with comprehensive guidance for implementing POF sensing technology in biomechanical research, contributing to the growing field of wearable healthcare monitoring and personalized movement analysis.

Advanced Applications in Biomedical Monitoring and Rehabilitation Systems

The integration of wearable robotics, including exoskeletons, prosthetics, and orthotic devices, is revolutionizing rehabilitative and assistive technologies. These systems augment human capabilities, restore lost functions, and provide quantitative feedback for clinical assessment. A predominant challenge in this field is developing sensor systems that are both highly sensitive to biomechanical parameters and capable of seamless integration into wearable devices without compromising comfort or functionality. Within this context, polymer optical fiber (POF) sensing technology emerges as a transformative solution. POF sensors offer a unique combination of flexibility, electromagnetic immunity, multiplexing capability, and biocompatibility, making them exceptionally suited for biomechanics research and application [29] [30]. These sensors facilitate the detailed measurement of critical parameters such as joint kinematics, human-robot interaction forces, and physiological signals, enabling more adaptive, intelligent, and user-centered wearable robotic systems. This document outlines the application and protocols for utilizing POF sensing in the development and evaluation of next-generation wearable robots.

Quantitative Performance of POF Sensors in Wearable Robotics

Polymer optical fiber sensors have been quantitatively validated for monitoring a wide spectrum of biomechanical parameters. Their performance in key sensing modalities is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of POF Sensors in Biomechanical Applications

| Sensing Modality | Measured Parameter(s) | Reported Performance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Modal Deformation [31] | Strain, Bending, Twisting, Pressing | - Strain Sensitivity (ΔI/ε): ~ -0.2- 2D Indentation Position Accuracy: ~99.17%- Combined Strain & Twist Accuracy: ~98.4% | Intelligent recognition of elastomer deformations for soft robotic proprioception. |

| Gait & Gesture Analysis [31] | Hand Gesture Recognition | - Recognition Accuracy: 99.38% | Intelligent glove for human-machine interaction and prosthetic control. |

| Integrated Clinic Monitoring [29] | Joint Angle, Interaction Force, Ground Reaction Force (GRF), Breath Rate | - Simultaneous monitoring of multiple devices (orthosis, exoskeleton, treadmill, wearable sensors).- Enabled by a single, multiplexed POF system. | Robot-assisted rehabilitation clinic, providing comprehensive patient assessment across different therapy stages. |

| Physiological Monitoring [27] | Body Temperature, Cardiorespiratory Rates, Sweat | - Multi-parameter and multi-point sensing from a compact form factor. | All-fibre wearable devices for continuous health supervision. |

Experimental Protocols for POF Sensor Integration

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing POF sensors in wearable robotics, from sensor fabrication to system-level validation.

Protocol: Fabrication of a Soft POF Sensor for Multi-Axial Deformation

This protocol details the creation of a sensitive POF sensor unit capable of detecting strain, bending, and torsion [31].

I. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials Table 2: Essential Materials for POF Sensor Fabrication

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Commercial POF (PMMA, 500 μm diameter) | The core sensing element; transmits light whose intensity is modulated by deformation. |

| Silicone Elastomer (e.g., Polydimethylsiloxane - PDMS) | Provides a flexible and supportive matrix for embedding sensors, mimicking mechanical properties of human tissue. |

| UV-Curable Adhesive (e.g., D-5604) | Fixes connections between POF segments and secures light sources/detectors. |

| Rubber Tubing | Houses the connected POF ends, creating a mechanical structure that deforms predictably under load. |

| Light-Emitting Diode (LED) | Serves as the light source injected into the POF. |

| High-Resolution Imaging Camera | Acts as the photodetector, capturing the output light intensity from multiple POFs simultaneously. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Fiber Preparation: Cut a commercial Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) POF to the desired length using a precision cleaver. Mechanically polish the output endface of the POF with a lapping film (e.g., 1 μm grit) to ensure a smooth surface for optimal light transmission [31].

- Sensor Assembly: Connect two prepared POF segments within a section of rubber tubing. Use UV glue to seal the connection, maintaining an initial air gap of approximately 700 μm between the fiber endfaces. Cure the assembly under a 365 nm UV light source for 30 seconds. The air gap is critical for sensitivity, as mechanical deformation alters the light coupling efficiency between the fibers [31].

- Light Source Integration: Attach an LED to the input endface of the assembled POF sensor. Secure the connection using UV glue and cure it. The typical coupled power should be around 28 μW [31].

- Embedding in Elastomer: For applications in soft robotics, embed the assembled POF sensor array into a silicone elastomer matrix (e.g., PDMS). This provides mechanical robustness and ensures proper strain transfer from the host material to the sensor [31].

- Signal Acquisition: Assemble the output ends of multiple POFs into a bundle. Use a high-resolution camera (e.g., Tucsen MIchrome 5 Pro) with a tube lens system to capture real-time images of the sensors' output light. The light intensity from each POF core is extracted and summed from the captured images to generate the sensor's output signal [31].

Protocol: Instrumentation of a Lower-Limb Exoskeleton for Gait Analysis

This protocol describes the integration of a multiplexed POF sensor system into a lower-limb exoskeleton and treadmill to monitor biomechanical parameters during gait assistance [29].

I. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials Table 3: Key Materials for Exoskeleton Instrumentation

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| POF Angle Sensors [29] | Measure joint angles (e.g., knee, hip) in the exoskeleton or orthosis. |

| POF Force Sensors [29] | Monitor human-robot interaction forces at the physical interface between the device and the user. |

| POF-Instrumented Treadmill [29] | Measures Ground Reaction Forces (GRFs) and identifies gait phases (stance, swing) during walking. |

| POF-Based Insole [29] | Enables GRF measurement and gait event detection during over-ground walking. |

| Multiplexing Interrogation System [29] | Allows multiple POF sensors (angle, force, GRF) to operate on a single optical fiber cable, reducing system complexity and cost. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sensor Calibration: Prior to integration, individually characterize and calibrate each POF sensor (angle and force) against known standards. For angle sensors, this involves correlating light attenuation with known joint angles. For force sensors, correlate output with known loads [29].

- Exoskeleton Integration: Mount the calibrated POF angle sensors on the exoskeleton's joint axes to measure kinematic data. Attach POF force sensors at key interface points (e.g., cuffs) to quantify interaction forces between the user and the robot [29].

- Treadmill Instrumentation: Integrate POF force sensors into the treadmill platform to measure vertical GRFs. This data is crucial for identifying the stance and swing phases of the gait cycle, which can be used for adaptive control of the exoskeleton [29].

- System Integration: Connect all POF sensors from the exoskeleton and treadmill to a single multiplexing interrogation system. This integrated approach allows for the simultaneous acquisition of kinematic and kinetic data from multiple points using a compact, low-cost system [29].

- Data Acquisition & Validation: Conduct gait trials with human subjects. Simultaneously collect data from the integrated POF system and a gold-standard motion capture system. Compare the results to validate the accuracy and reliability of the POF sensor network [29].

Visualization of Workflows and System Architectures

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core workflows and logical relationships in POF-based wearable robotic systems.

POF Sensor Data Acquisition Workflow

Integrated Rehabilitation Clinic Sensing Architecture

Human gait analysis provides critical insights into an individual's neurological, musculoskeletal, and cardiorespiratory health, serving as a vital tool in clinical diagnostics, rehabilitation, and sports science [14] [32]. Plantar pressure measurement, which quantifies the distribution of forces under the foot during standing and walking, constitutes a fundamental component of comprehensive gait analysis [33] [34]. These measurements enable researchers and clinicians to identify aberrant loading patterns associated with various pathologies, including diabetic foot ulcers, musculoskeletal disorders, and neuromuscular conditions [33] [35]. Traditional sensing technologies, including force platforms and electronic pressure sensors, present limitations such as electromagnetic interference, limited portability, and reduced compliance in extended monitoring scenarios [14] [25]. Polymer optical fiber (POF) sensors have emerged as a promising technology that addresses these limitations through their inherent advantages, including electromagnetic immunity, flexibility, biocompatibility, and compatibility with wearable monitoring systems [33] [14] [36]. These application notes provide a comprehensive technical framework for implementing POF-based sensing systems for gait monitoring and plantar pressure measurement within biomechanics research.

Polymer Optical Fiber Sensing Technology

Fundamental Principles and Advantages

Polymer optical fiber sensors operate based on the modulation of light properties—including intensity, wavelength, phase, or polarization—in response to external mechanical deformations induced by human movement [25] [36]. Unlike conventional silica optical fibers, POFs are fabricated from plastic polymers such as polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), granting them superior flexibility, higher elastic strain limits, greater fracture toughness, and enhanced impact resistance [14] [36]. These material properties make POFs exceptionally suitable for biomechanical applications where repeated large deformations occur, such as in gait analysis and plantar pressure monitoring [33] [14].

The operational principles of POF sensors in gait analysis primarily utilize intensity-based or Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG)-based sensing mechanisms. Intensity-based sensors measure light attenuation caused by macro-bending of the fiber, which occurs when pressure is applied to the insole, leading to a measurable decrease in transmitted optical power [33]. FBG-based sensors rely on periodic refractive index structures inscribed within the fiber core that reflect specific wavelengths of light; external strain or pressure shifts this Bragg wavelength, enabling precise quantification of mechanical loading [25] [35].

Table 1: Comparison of POF Sensing Technologies for Gait Analysis

| Feature | Intensity-Based POF Sensors | FBG-Based POF Sensors |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Macro-bend light attenuation [33] | Wavelength shift of reflected light [25] |

| Interrogation Cost | Low-cost light sources and photodetectors [33] | Higher cost specialized equipment [37] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited, requires multiple photodetectors [33] | High, wavelength-division multiplexing possible [25] |

| Sensitivity | Moderate, sufficient for gait phases [33] | High, capable of detecting subtle pressure variations [35] |

| Temperature Sensitivity | Low, minimal cross-sensitivity [33] | High, requires compensation techniques [25] |

| Implementation Complexity | Simple signal processing [33] | Complex demodulation algorithms [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for POF-Based Gait Analysis Research

| Component | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Fiber | Step-index PMMA POF (core: 980 μm, total diameter: 2 mm) [33] | Primary sensing element; transmits optical signals modulated by mechanical deformation |

| Interrogation System | Photodetectors for intensity-based systems; Optical Spectrum Analyzer (OSA) for FBG systems [33] [35] | Converts optical signals to quantifiable electrical measurements or wavelength data |

| Insole Material | Ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) or Polypropylene (PP) with 2-17 mm thickness variation [33] | Provides mechanical support and housing for sensors while allowing natural foot biomechanics |

| Encapsulation Material | Silicone rubber or thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) [35] | Protects sensing elements from moisture and mechanical damage while ensuring proper force transmission |

| Optical Components | Broadband light source, optical circulators, connectors [35] | Establishes optical paths for signal transmission and reflection |

| Data Acquisition | Microprocessor (e.g., nRF52840) with Bluetooth module for wireless transmission [34] | Enables real-time data capture, processing, and transmission to analysis platforms |

| Calibration Equipment | Universal testing machine or commercial force platforms [33] | Provides reference measurements for sensor calibration and validation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Design and Fabrication of POF Plantar Pressure Insoles

Objective: To fabricate a functional plantar pressure insole instrumented with polymer optical fiber sensors for gait analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- Step-index PMMA POF (e.g., HFBR-R/EXXYYYZ) with 980 μm core diameter and 2 mm total diameter [33]

- Ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) insole material (17 mm heel, 2 mm forefoot thickness) [33]