Optical vs. Mechanical Gait Analysis: A Comparative Evaluation for Biomedical Research and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of optical and mechanical gait analysis systems, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Optical vs. Mechanical Gait Analysis: A Comparative Evaluation for Biomedical Research and Clinical Applications

Abstract

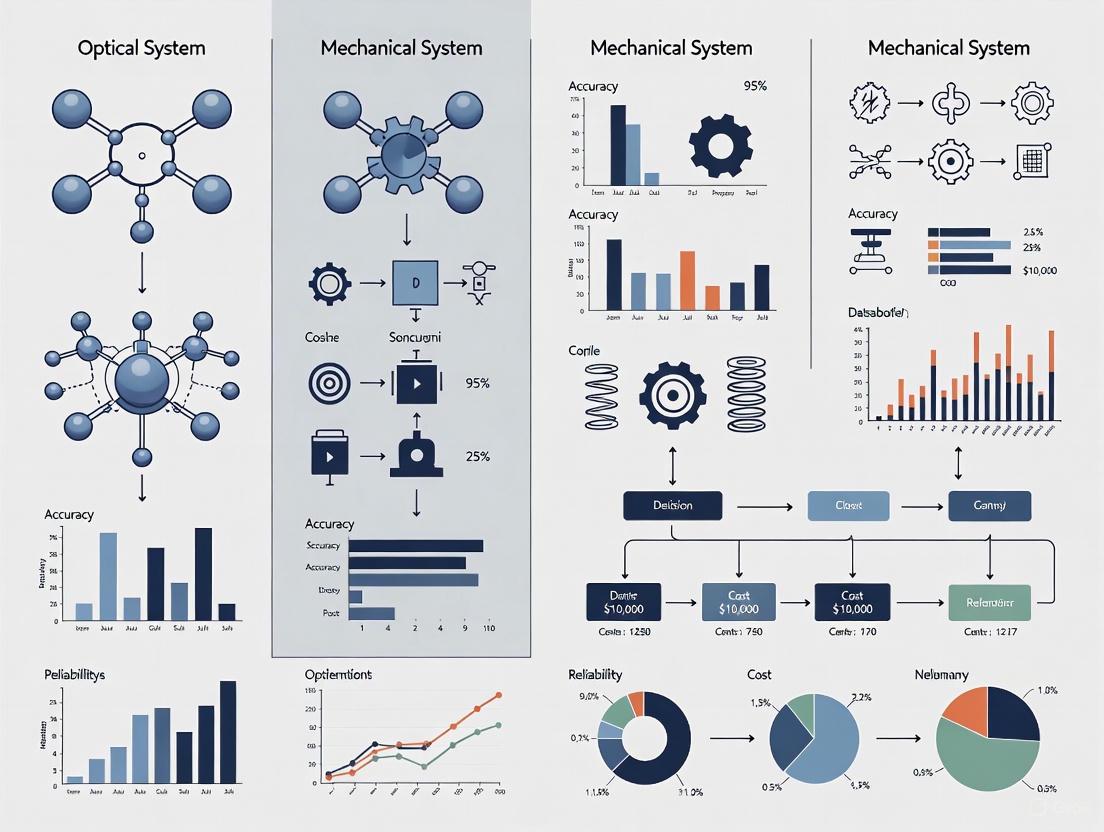

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of optical and mechanical gait analysis systems, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both technologies, from marker-based motion capture to markerless computer vision and wearable sensors. The methodological section details practical applications across clinical and research settings, including use cases in neurology, orthopedics, and sports science. The review addresses key challenges in system validation, data processing, and integration, offering troubleshooting strategies for real-world implementation. A critical comparative analysis evaluates the precision, scalability, and cost-effectiveness of each approach, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on emerging trends like AI-driven analytics and multimodal system integration that are poised to transform biomechanical assessment in clinical trials and therapeutic development.

Core Principles and Technological Evolution of Gait Analysis Systems

Gait analysis has evolved from early observational methods into a sophisticated field where quantitative data informs clinical diagnosis and treatment planning. Two dominant methodologies have emerged: optical motion capture, often considered the laboratory gold standard, and mechanical sensing through wearable sensors like Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), which enable real-world monitoring. While optical systems provide high-precision kinematic data in controlled environments, mechanical wearable sensors offer unparalleled portability for ecological assessments. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and experimental validation of these technologies, drawing upon current research to aid researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate methodologies for specific research contexts.

Technology Comparison: Core Specifications and Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize the fundamental characteristics and performance data of optical and mechanical gait analysis systems, highlighting their distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Technical Specifications and Operational Characteristics

| Feature | Optical Motion Capture (Marker-Based) | Mechanical Sensing (Wearable IMUs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Technology | Infrared cameras tracking reflective markers [1] [2] | Accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers [3] |

| Spatial Accuracy | Sub-millimeter precision for marker position [2] | Accuracy dependent on sensor placement and calibration; dynamic accuracy for roll/pitch reported at < 1° RMS [3] |

| Data Output | 3D trajectories of body markers/joints [1] | 3-axis acceleration, angular velocity, and orientation [1] [3] |

| Sample Rate | High-frequency (e.g., 85-100 Hz) [1] [4] | Typically 100 Hz [1] [3] |

| Operational Environment | Controlled laboratory setting [2] [5] | Unrestricted; supports indoor and outdoor use [1] [3] |

| Setup Time & Complexity | High (marker placement, system calibration) [6] | Low (don sensors and calibrate) [6] |

| Key Advantage | High precision, comprehensive whole-body kinematics | Portability, cost-effectiveness, and real-world applicability [1] |

| Key Limitation | Limited to lab environment, sensitive to marker occlusion [2] | Susceptible to drift and soft tissue artifact [5] |

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Gait Parameter Extraction

| Performance Metric | Optical Systems (Marker-Based & Markerless) | Wearable IMU Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Spatio-Temporal Parameters (e.g., speed, cadence) | High accuracy for all parameters [1] | High agreement with optical standards; validated for clinical use [3] |

| Sagittal Plane Kinematics (Knee, Ankle) | Gold standard. Markerless shows RMSD <5° for ankle angles [4] [6] | Algorithms for joint angle estimation require further enhancement [1] |

| Frontal/Transverse Plane Kinematics | Affected by soft tissue artifact and anatomical landmark uncertainty [2] | Challenging due to sensor drift and calibration [5] |

| Test-Retest Reliability | Markerless systems show good reliability (SEM <5°) for level walking and ramps [6] | Provides reliable day-to-day measurements in real-world protocols [3] |

| Interchangeability with Gold Standard | Markerless is a credible, complementary tool but not yet fully interchangeable for all clinical decisions [4] | Validated for specific parameters (e.g., event detection); not a direct replacement for full kinematics [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Robust validation is critical for adopting any gait analysis technology. Below are detailed methodologies from key recent studies.

Protocol for Multi-Sensor Dataset Collection (NONSD-Gait)

A 2025 study created a public dataset to enable cross-device comparisons and analysis under non-standardized dual-task conditions [1].

- Participants: 23 healthy adults (9 males, 14 females) aged 21-30 with no neuromuscular or skeletal impairments [1].

- Sensor Configuration:

- Optical MOCAP: 8 optical cameras (NOKOV MARS 2H) at 100 Hz, tracking 22 reflective markers placed on the body according to the Plug-in-Gait model [1].

- Depth Camera: One Microsoft Kinect V2.0 camera placed 1.8 m from the walkway, recording 3D trajectories of 25 body joints at 30 Hz [1].

- Mechanical IMU: One Witmotion sensor (100 Hz) placed on the left ankle, recording 3D acceleration, angular velocity, and orientation [1].

- Gait Tasks: Participants performed back-and-forth 7 m walks under single-task and three non-standardized dual-task conditions (texting, web browsing, holding a cup) [1].

- Data Processing: Trajectory data from all sensors were processed to extract 10 spatio-temporal and 168 kinematic gait parameters, allowing for synchronized cross-sensor comparison and analysis [1].

Protocol for Validating Markerless System Reliability

A 2025 study evaluated the day-to-day reliability of a markerless system (Theia3D) in a simulated living laboratory [6].

- Participants: 21 healthy adults (14 males, 7 females) with an average age of 31.1 [6].

- System Configuration: 27 synchronized video cameras (60 Hz) deployed throughout a living laboratory designed to mimic home indoor and outdoor environments, including level ground, ramps, and stairs [6].

- Gait Tasks: On two separate days, participants performed five tasks: level walking, ramp ascent, ramp descent, stair ascent, and stair descent. Each task was repeated five times [6].

- Data Analysis: 3D joint kinematics were processed using Theia3D and analyzed in Visual3D. Absolute reliability was assessed using root mean square difference (RMSD) for full gait cycles and standard error of measurement (SEM) for discrete gait events [6].

- Key Outcome: The system demonstrated high reliability for level walking and ramp descent (SEM < 5°), though RMSD for knee flexion during ramp and stair ascent slightly exceeded 5°, reflecting the system's sensitivity to changing gait demands [6].

Protocol for Clinical IMU Dataset Collection

A 2025 study presented a large clinical dataset to validate IMUs for gait quantification across pathologies [3].

- Participants: 260 participants, including healthy individuals and patients with neurological (Parkinson's, stroke) or orthopedic (osteoarthritis, ACL injury) conditions [3].

- Sensor Configuration: Four IMUs (Xsens or Technoconcept) were placed on the head, lower back (L4/L5), and the dorsal part of each foot. Data was recorded at 100 Hz [3].

- Gait Protocol: A standardized 10-meter walk test with a 180° turn. Participants started and ended with a static stand, walking at a comfortable pace [3].

- Data Output: The dataset comprises over 11 hours of gait time-series data, facilitating the study of kinematic parameters, gait cycles, and the development of algorithms for quantifying pathological gait [3].

System Architectures and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the typical data capture and processing workflows for optical and mechanical gait analysis systems.

Optical Motion Capture Workflow

Wearable IMU System Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for Gait Analysis Research

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reflective Markers [1] | Physical Reagent | Enable optical motion capture systems to track 3D body segment movements. |

| Plug-in Gait Model [1] [2] | Biomechanical Model | A standardized model for calculating lower and upper body kinematics and kinetics from marker trajectories. |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) [1] [3] | Sensor | Measures tri-axial acceleration, angular velocity, and orientation for portable gait analysis. |

| Theia3D [4] [6] | Markerless Motion Capture Software | Uses deep learning and computer vision to estimate 3D kinematics from video without physical markers. |

| Visual3D [4] [6] | Biomechanical Analysis Software | A platform for processing motion capture data, applying biomechanical models, and computing gait parameters. |

| OpenSim [7] | Open-Source Simulation Platform | Performs musculoskeletal modeling and simulation, including inverse kinematics to estimate joint angles. |

| SHAP/LIME [5] | Explainable AI (XAI) Framework | Provides post-hoc interpretations of "black-box" machine learning models used in gait analysis, identifying influential input features. |

The delineation between optical and mechanical gait analysis is no longer a simple hierarchy but a strategic choice based on research objectives. Optical systems, including emerging markerless technologies, remain indispensable for high-fidelity kinematic assessment in controlled settings, providing the benchmark against which other technologies are validated [4] [6]. Conversely, mechanical sensing via IMUs has matured into a robust methodology for capturing ecologically valid gait data across diverse populations and real-world environments [3]. The future of gait analysis lies not in the supremacy of one technology over the other, but in their complementary integration and the application of AI to enhance data interpretation, ultimately driving forward personalized medicine and clinical diagnostics [8] [5].

Human gait analysis provides a critical window into neuromuscular health, disease progression, and treatment efficacy. The systematic quantification of walking patterns relies on sophisticated technologies that can be broadly categorized into optical systems (non-wearable) and mechanical systems (wearable sensors). Optical motion capture systems, considered the gold standard in biomechanical research, utilize cameras to track body movement in laboratory environments [9] [10]. These systems typically employ infrared cameras that capture reflective markers placed on anatomical landmarks, enabling precise reconstruction of three-dimensional movement with millimeter accuracy. Complementing these are mechanical systems based on wearable sensors – including inertial measurement units (IMUs), force-sensitive resistors, and pressure sensors – that capture motion and force data outside controlled laboratory settings [9]. These technologies provide researchers with complementary approaches for quantifying the complex biomechanics of human locomotion, each with distinct strengths for specific research applications.

The fundamental difference between these approaches lies in their operational principles and measurement environments. Optical systems excel at capturing spatial kinematics through direct visualization of segmental movement, while mechanical systems often provide better temporal resolution of dynamic parameters through continuous monitoring. Modern research increasingly leverages both technologies in hybrid configurations to capitalize on their complementary advantages, though understanding their inherent capabilities and limitations remains essential for proper experimental design [11]. This comparative analysis examines the key gait parameters measurable by each system type, their underlying methodologies, and their applications in research settings.

Key Biomechanical Parameters in Gait Analysis

Classification of Gait Parameters

Gait parameters are systematically categorized into three primary domains that collectively describe locomotion mechanics. Spatiotemporal parameters provide the fundamental metrics of walking patterns, including timing and distance measurements. Kinematic parameters describe the body's motion without reference to forces, focusing on joint and segment movements. Kinetic parameters quantify the forces responsible for producing observed movements, offering insights into muscle function and joint loading [12] [10].

The most clinically and scientifically valuable parameters span all three domains. Gait velocity – the product of step length and cadence – serves as a particularly sensitive indicator of overall gait performance and has been described as a vital sign in mobility assessment [9] [13]. Joint angle patterns reveal critical information about movement strategies and compensatory mechanisms, while ground reaction forces provide fundamental data about limb loading and propulsion characteristics [14] [10]. The table below organizes the essential parameters measured in comprehensive gait analysis:

Table 1: Essential Gait Parameters Categorized by Biomechanical Domain

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | Kinematic Parameters | Kinetic Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Gait velocity [9] | Joint angles (hip, knee, ankle) [10] | Ground reaction forces (GRF) [9] |

| Cadence (steps/minute) [9] | Segment trajectories [15] | Joint moments [10] |

| Step length [9] | Range of motion [10] | Center of pressure (COP) [9] |

| Stride length [9] | Body postures [15] | Power generation/absorption [10] |

| Step width [9] | Foot placement [15] | Pressure distribution [13] |

| Stance/swing phase timing [9] | Trunk inclination [9] | Muscle activation (EMG) [9] |

Parameter Significance in Research and Clinical Applications

Different gait parameters offer distinct insights into neuromuscular function and pathology. In Parkinson's disease research, for example, reduced stride length and decreased gait velocity represent primary motor manifestations, while increased step width often indicates compensatory balance strategies [10]. Similarly, joint moment patterns and power generation characteristics at the ankle provide critical information about propulsion deficits in neurological conditions and obesity-related gait adaptations [10] [13].

The integration of multiple parameter domains enables comprehensive biomechanical profiling. For instance, combining kinematic data (joint angles) with kinetic information (joint moments) allows researchers to calculate joint stiffness and mechanical work – derived parameters that offer profound insights into movement efficiency and pathology [10]. This multidimensional approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development, where objective gait parameters serve as sensitive biomarkers for treatment efficacy and disease modification across numerous neurological and musculoskeletal conditions.

Optical Gait Analysis Systems

Technology and Measurement Principles

Optical gait analysis systems operate on the principle of triangulation, using multiple cameras to reconstruct the three-dimensional positions of markers placed on anatomical landmarks. These systems primarily employ two approaches: marker-based and markerless technologies. Marker-based systems, considered the reference standard for research, use passive reflective or active light-emitting markers tracked by infrared cameras sampling at frequencies typically between 100-1000 Hz [15]. The resulting trajectory data undergoes mathematical modeling to compute segment motions and joint centers, enabling precise kinematic measurement.

More recently, markerless motion capture has emerged as a promising alternative that uses advanced computer vision algorithms to track body segments without physical markers. These systems employ depth sensors (e.g., Microsoft Kinect) or multiple synchronized RGB cameras that capture natural movement without marker application constraints [15]. The raw video data is processed using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and pose estimation algorithms (e.g., OpenPose) to identify anatomical landmarks and reconstruct skeletal models. This approach reduces preparation time and eliminates marker-related artifacts, though with potential trade-offs in measurement precision compared to marker-based systems [15].

Experimental Protocols for Optical Systems

Standardized laboratory protocols ensure consistent data collection across research settings. A typical optical gait analysis protocol involves:

Laboratory Setup: Installation of 8-12 infrared cameras positioned around a 10-meter walkway, with force plates embedded in the center to capture ground reaction forces synchronized with motion data [10].

System Calibration: Dynamic and static calibration procedures establish a global coordinate system and define volume accuracy. This includes wand waving for space calibration and static trials for defining anatomical relationships [15].

Marker Placement: Application of retroreflective markers following established biomechanical models (e.g., Plug-in-Gait, Cleveland Clinic, Helen Hayes marker sets) on predetermined anatomical landmarks [10].

Data Collection: Participants walk at self-selected speeds across the walkway, with multiple trials captured to ensure representative data. For pathological populations, additional conditions like dual-task walking may be incorporated [10].

Data Processing: Trajectory gap filling, filtering, and computation of kinematic and kinetic variables using inverse dynamics approaches [15].

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Major Optical Gait Analysis Systems

| System Type | Measurement Principle | Key Parameters Measured | Accuracy | Sample Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker-based Optoelectronic [10] | Infrared cameras + reflective markers | 3D joint kinematics, spatiotemporal parameters | High (sub-millimeter) | 100-1000 Hz |

| Force Plates [10] | Piezoelectric or strain gauge sensors | Ground reaction forces, center of pressure | High (<1% error) | 100-2000 Hz |

| Depth Cameras [15] | Infrared pattern projection | Markerless kinematics, spatiotemporal parameters | Moderate | 30-60 Hz |

| Multi-camera Markerless [15] | Computer vision + pose estimation | Body segment trajectories, joint angles | Moderate to High | 60-200 Hz |

Mechanical Gait Analysis Systems

Technology and Measurement Principles

Mechanical gait analysis systems employ wearable sensors directly attached to the body to capture movement and force data during locomotion. The core technology includes inertial measurement units (IMUs) containing tri-axial accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers that segment motion into translational and rotational components [9]. These sensors measure temporal changes in velocity, orientation, and position through sensor fusion algorithms, enabling computation of gait parameters without spatial constraints.

Complementing IMUs, pressure measurement systems provide mechanical data through force-sensitive resistors or capacitive sensors embedded in shoe insoles or walkway mats. These systems capture vertical ground reaction forces, pressure distribution patterns, and temporal loading characteristics during gait [13]. Advanced versions incorporate electromyography (EMG) sensors to monitor muscle activation patterns synchronized with movement data, providing a comprehensive neuromotor perspective on gait mechanics [9].

Experimental Protocols for Mechanical Systems

Standardized protocols ensure reliable data collection across mechanical system applications:

Sensor Configuration: Strategic placement of IMUs on body segments (typically feet, shanks, thighs, and pelvis) using hypoallergenic adhesives or elastic straps. Sensor-to-segment alignment follows anatomical axes [9].

System Calibration: Static upright calibration establishes sensor orientation relative to gravitational vertical. For some systems, functional movements define joint centers [9].

Data Collection: Participants walk predetermined courses or perform activities of daily living while sensors stream data wirelessly to base stations. Protocols often include varied conditions (level walking, stairs, obstacles) [9].

Data Processing: Sensor fusion algorithms (Kalman filters, complementary filters) convert raw inertial data to orientation estimates. Gait event detection algorithms identify heel strikes and toe-offs from accelerometer and gyroscope signals [9].

Table 3: Technical Specifications of Major Mechanical Gait Analysis Systems

| System Type | Measurement Principle | Key Parameters Measured | Accuracy | Sample Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) [9] | Accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer | Spatiotemporal parameters, segment orientation | Moderate (2-5° joint angle error) | 50-200 Hz |

| Pressure-Sensing Walkways [13] | Capacitive or resistive sensors | Step timing, force, pressure distribution | High (>95% step detection) | 100-500 Hz |

| Instrumented Insoles [9] | Force-sensitive resistors | Plantar pressure, gait phases, step count | Moderate to High | 50-100 Hz |

| Wearable EMG Systems [9] | Surface electromyography | Muscle activation timing, amplitude | High (depends on skin preparation) | 100-2000 Hz |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Parameter Measurement Capabilities

Direct comparison of optical and mechanical systems reveals distinct performance characteristics across gait parameter domains. Optical systems demonstrate superior accuracy for kinematic measurements, with marker-based systems achieving joint angle errors below 1° under ideal conditions [15]. This precision makes them indispensable for applications requiring detailed movement analysis, such as surgical planning and prosthesis design. Mechanical systems, while generally less accurate for absolute joint kinematics, provide excellent temporal resolution for detecting gait events (heel strike, toe-off) with accuracy exceeding 95% compared to force plate standards [9].

For spatiotemporal parameters, both technologies show strong agreement in controlled settings, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.95 for gait velocity, stride length, and cadence measurements [9] [13]. However, mechanical systems maintain measurement fidelity during extended monitoring outside laboratory environments, where optical systems cannot function. For kinetic analysis, optical systems paired with force plates provide the most comprehensive assessment of ground reaction forces and derived joint moments, while wearable pressure insoles offer practical alternatives for estimating vertical loading parameters in ecological settings [13].

Table 4: System Comparison Based on Key Research Application Criteria

| Performance Characteristic | Optical Systems | Mechanical Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Kinematic Accuracy | High (sub-millimeter, <1°) [15] [10] | Moderate (2-5° joint angle error) [9] |

| Temporal Parameter Accuracy | High (>95%) [10] | High (>95%) [9] [13] |

| Kinetic Measurement Capability | High (with force plates) [10] | Moderate (pressure distribution only) [13] |

| Environmental Constraints | Laboratory only [9] | Natural environments [9] |

| Setup Complexity | High (calibration, marker placement) [15] | Low to Moderate [9] |

| Data Richness | Comprehensive kinematics + kinetics [10] | Selective parameters [9] |

| Participant Burden | Moderate (markers, limited area) [15] | Low (after initial setup) [9] |

Application in Disease-Specific Research

The selection between optical and mechanical systems depends heavily on the specific research context and population. In Parkinson's disease research, optical systems have revealed characteristic reductions in hip, knee, and ankle range of motion, and decreased joint moments and power generation during push-off [10]. These detailed kinematic and kinetic profiles provide sensitive markers of disease progression and treatment response. Mechanical systems, particularly wearable IMUs, effectively capture the high gait variability and freezing of gait episodes that characterize advanced Parkinson's disease during continuous monitoring [9].

In obesity research, optical systems demonstrate altered knee and hip mechanics during controlled walking, while pressure-sensing walkways reveal significant differences in maximum force (healthy: 84.9% body weight, obese: 93.8% body weight) and peak pressure distributions between groups [13]. For multiple sclerosis, optical systems quantify subtle balance impairments through center-of-mass displacement measures, while wearable sensors track fatigue-related gait deterioration over extended walking periods [9] [11]. This disease-specific performance highlights the complementary value of both technologies across the research spectrum.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Equipment and Software for Gait Analysis Research

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Retroreflective Markers | Define anatomical landmarks and segment frames | Optical motion capture [15] [10] |

| Calibration Frames | Establish laboratory coordinate system and scale | Optical system calibration [15] |

| Wireless IMU Sensors | Capture segment acceleration, angular velocity, orientation | Wearable gait analysis [9] |

| Pressure-Sensing Walkway | Measure step timing, force, and pressure distribution | Laboratory-based gait assessment [13] |

| Instrumented Insoles | Monitor plantar pressure distribution in shoes | Ambulatory pressure measurement [9] |

| Surface EMG Electrodes | Record muscle activation patterns during gait | Neuromuscular analysis [9] |

| Biomechanical Modeling Software | Calculate joint kinematics and kinetics from raw data | Data processing and analysis [15] [10] |

Implementation Considerations for Research Settings

Selecting appropriate gait analysis technology requires careful consideration of research objectives, participant characteristics, and resource constraints. For pharmaceutical trials assessing disease-modifying effects, optical systems provide the precision needed to detect subtle treatment effects on specific gait components [10]. Conversely, for functional mobility assessment focusing on real-world performance, mechanical systems offer superior ecological validity through extended monitoring [9].

Hybrid approaches that combine brief laboratory assessments with optical systems and extended monitoring using wearable sensors provide comprehensive data across controlled and ecological contexts [11]. This approach is particularly valuable in neurodegenerative disease research, where both precise movement quantification and natural performance patterns are needed to fully characterize therapeutic outcomes. Regardless of technology selection, standardization of protocols, rigorous operator training, and consistent data processing methodologies remain essential for generating valid, comparable research data across sites and studies.

Optical and mechanical gait analysis systems offer complementary approaches for quantifying human locomotion, each with distinct advantages for specific research scenarios. Optical systems provide unparalleled precision for detailed kinematic and kinetic analysis under controlled laboratory conditions, making them ideal for mechanistic studies and intervention trials requiring high sensitivity to change [15] [10]. Mechanical systems excel at capturing ecologically valid gait performance during extended monitoring in natural environments, providing unique insights into functional mobility and daily activity patterns [9].

The ongoing integration of artificial intelligence and computer vision technologies is blurring the distinction between these approaches, with markerless optical systems becoming more portable and wearable systems achieving greater accuracy [16] [15]. These advancements promise to expand the applications of quantitative gait assessment in both research and clinical practice, potentially enabling more sensitive drug efficacy evaluation and personalized rehabilitation approaches. For the contemporary researcher, understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate implementation contexts for both optical and mechanical systems remains essential for designing methodologically sound studies that advance our understanding of human locomotion.

Optical motion capture systems are indispensable tools in biomechanics, sports science, and clinical research, providing non-invasive means to quantify human movement. These technologies primarily fall into two categories: marker-based systems, which use reflective markers tracked by infrared cameras, and markerless systems, which leverage computer vision and artificial intelligence to estimate pose from standard video [17] [18]. A third technology, depth sensing, which uses structured light or time-of-flight cameras to capture three-dimensional data, often serves as a foundational element in many markerless solutions and standalone depth perception applications [19] [20].

The evaluation of these systems is critical for research and clinical practice. As noted by the Sports Technology Research Network (STRN) Quality Framework, accuracy depends not only on the system itself but also on protocols, models, and data collection personnel [21]. This guide provides a objective comparison of these optical technologies, focusing on their performance characteristics, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform selection for specific applications, particularly within the context of gait analysis research.

Technology Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, performance data, and ideal use cases for each optical motion capture technology.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Optical Motion Capture Technologies

| Feature | Marker-Based Systems | Markerless Systems | Depth Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Tracks reflective markers on anatomical landmarks [18] | Computer vision & AI to estimate pose from RGB/RGBD video [17] | Measures distance using structured light or time-of-flight [20] |

| Typical Accuracy | Sub-millimeter to 2 mm dynamic error [22]; Joint angles: 3-5° error [18] | Joint angles: 3-15° RMSE, varies by plane [22]; Model scaling: within 3-4 cm [21] | Varies with setup; specialized software can calculate theoretical accuracy limits [20] |

| Key Strength | High precision; considered the laboratory "gold standard" [22] [18] | Ecological validity; fast setup; non-intrusive [17] [22] | Direct 3D data capture; useful for real-world object scanning and mapping |

| Primary Limitation | Time-consuming setup; operator-dependent; can affect natural movement [17] [18] | Sensitive to environment (lighting, clothing); can be less precise for fine rotations [21] [22] | Limited range; accuracy can be affected by environmental light and surface properties |

| Best For | Controlled lab research and clinical biomechanics requiring highest precision [22] | Team screening, real-world movement analysis, and high-throughput testing [22] | Integration with other systems (XR, mobile devices) for depth perception and mapping [19] |

Performance and Validation Data

Quantitative comparisons reveal the specific performance trade-offs between these systems. A 2023 study compared marker-based and markerless systems during a lunge exercise, analyzing the agreement for joint angles in the sagittal (flexion/extension), frontal (abduction/adduction), and transverse (rotation) planes [18]. The findings illustrate that while the systems generally track similar movement patterns, the level of agreement is joint and plane-specific.

Table 2: Summary of Agreement between Marker-Based and Markerless Systems for Joint Angles Data derived from a 2023 study using 95% functional limits of agreement (fLoA) [18]

| Joint & Motion Plane | Typical Bias (Markerless vs. Marker-Based) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Knee (Flexion/Extension) | Minimal bias | Good agreement between systems, particularly for high-range movements. |

| Hip (All Planes) | Variable | Flexion showed better agreement than abduction and rotation. |

| Spine (All Planes) | Significant bias, direction varied by plane | Lowest agreement, requiring data transformation to align coordinate systems. |

In gait analysis, a 2022 study found that a markerless system produced spatio-temporal parameters (e.g., gait speed, cadence) similar to a marker-based system [17]. For joint kinematics, the markerless system comparably captured hip and knee angles but showed a slight underestimation of the maximum flexion for ankle and knee joints [17]. A 2025 review of sports validation studies further clarified that markerless systems demonstrate strong reliability for most sport-specific tasks, with Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values typically ranging from 3–15° in the sagittal plane, 2–9° in the frontal plane, and exhibiting a wider range in the transverse plane, where motion is smaller and more challenging to capture [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the validity of the data presented, understanding the underlying experimental methodologies is crucial. The following protocols are representative of rigorous comparative studies.

Protocol 1: Evaluating XR Device Tracking and Depth Perception

A 2025 study evaluated the 6-DoF (Degrees of Freedom) tracking accuracy and depth perception of commercial XR devices like the HTC Vive XR Elite and Magic Leap 2, which rely on inside-out tracking and depth sensing [19].

1. Objective: To determine the tracking accuracy, depth perception error, and drift accumulation of XR devices for industrial applications [19]. 2. Equipment: - Ground Truth System: Vicon motion capture system (8 Vero cameras), accurate to sub-millimeter levels [19]. - Test Devices: HTC Vive XR Elite (video pass-through) and Magic Leap 2 (optical pass-through) [19]. - Software: Custom XR application built in Unity using the OpenXR SDK [19]. 3. Environment: A factory shop floor-like open space of 6 m x 4 m to replicate real-world challenges [19]. 4. Procedure: - The XR devices were affixed with reflective markers for the Vicon system to track. - A calibration step established a common coordinate system between the Vicon and the XR device's native tracking space using fiducial markers. - Participants walked freely within the space while both systems recorded positional and rotational data in real-time. - Depth perception was tested by having users align virtual objects at varying distances, with the Vicon system providing the ground truth measurement [19]. 5. Data Analysis: The 6-DoF pose data (X, Y, Z, pitch, yaw, roll) from the XR devices was continuously compared against the Vicon's ground truth to calculate positional errors and rotational drifts over time [19].

The workflow for this validation method is systematized below:

Protocol 2: Comparing Markerless and Marker-Based Gait Analysis

A 2022 study presented a protocol for comparing a multi-camera markerless system against a gold-standard marker-based system for 3D gait analysis [17].

1. Objective: To validate a markerless pipeline for extracting spatio-temporal and kinematic gait parameters against a marker-based system [17]. 2. Equipment: - Marker-Based System: Optitrack motion capture system. - Markerless System: Multiple synchronized RGB cameras (e.g., 3x Mako G125 cameras). - Software: Custom pipeline using Pose ResNet-152 for 2D keypoint detection and Adafuse for multi-view refinement, followed by 3D reconstruction [17]. 3. Participants: 16 healthy subjects walking a 6-meter path [17]. 4. Procedure: - Participants were equipped with reflective markers for the Optitrack system. - They performed walking trials, which were recorded simultaneously by both systems. - The markerless system's videos were processed through the pipeline to estimate 3D keypoints (joint positions). - Data from both systems were processed through the same biomechanical model (e.g., in OpenSim) to compute joint angles and spatio-temporal parameters like gait speed and stride length [17]. 5. Data Analysis: Agreement was assessed using statistical methods like functional limits of agreement (fLoA) or by directly comparing key outcome measures like joint angle waveforms and spatio-temporal parameters [17] [18].

The following diagram outlines the data flow in a typical markerless motion capture pipeline:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers aiming to implement or validate these technologies, the following table lists key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Optical Motion Capture Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Motion Capture System | Provides high-accuracy ground truth data for validation studies. | Vicon or Qualisys systems with infrared cameras tracking reflective markers [19] [18]. |

| Calibration Tools | Ensures spatial accuracy of the capture volume. | L-Frame, T-Wand, or calibration board used to define origin and scale [18]. |

| Reflective Markers | Define anatomical segments and landmarks for marker-based tracking. | 19mm spherical markers placed according to ISB guidelines [18]. |

| Biomechanical Modeling Software | Processes raw marker or keypoint data into biomechanically meaningful outputs. | Visual3D, OpenSim, or similar software to calculate joint kinematics and kinetics [17] [18]. |

| Multi-camera RGB Setup | The core hardware for markerless motion capture. | Synchronized cameras (e.g., 3-8 units) surrounding the capture volume to provide multiple viewpoints [17]. |

| Pose Estimation Algorithm | The software engine that identifies human body keypoints from video. | Deep learning models like Pose ResNet or integrated commercial software (e.g., Theia3D) [17] [22]. |

| Validation & Statistical Framework | Methods to quantitatively assess agreement between systems. | Functional Limits of Agreement (fLoA), Linear Mixed-Effects Models (LMM), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [23] [18]. |

The choice between marker-based, markerless, and depth-sensing optical systems is not a matter of identifying a single superior technology, but rather of matching the technology's strengths to the research question. Marker-based systems remain the benchmark for high-precision laboratory studies where control is paramount. In contrast, markerless systems offer unparalleled advantages for studies requiring ecological validity, minimal setup time, and the ability to collect data from large cohorts or in real-world environments. Depth sensing acts as a critical enabling technology, particularly for integrated systems like XR headsets.

The convergence of these technologies is shaping the future of movement science. As markerless algorithms continue to improve and validation frameworks become more sophisticated, the gap in accuracy for many clinical and sports applications will likely narrow further. Researchers are now empowered to adopt a tiered approach, leveraging the precision of marker-based systems for foundational validation and the scalability of markerless systems for widespread application, thus enriching the overall scope and impact of gait analysis and human movement research.

The objective quantification of human movement is fundamental to advancements in sports science, clinical diagnostics, and pharmaceutical development. Among the tools available for biomechanical analysis, mechanical and inertial systems—specifically force plates, pressure-sensitive walkways, and wearable inertial sensors—play a critical role. This guide provides a objective comparison of these three core technologies, framing them within a broader research context that often contrasts optical versus mechanical gait analysis methodologies. Whereas optical systems (e.g., marker-based motion capture) are often considered a gold standard for laboratory research, mechanical and inertial systems offer distinct advantages in terms of portability, cost, and applicability in real-world environments [24] [25]. This document summarizes their operational principles, performance characteristics based on recent experimental data, and detailed methodologies to inform researchers and professionals in their selection and application.

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics, strengths, and limitations of the three mechanical system types.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Mechanical Gait Analysis Systems

| Feature | Wearable Inertial Sensors (IMUs) | Pressure-Sensitive Walkways | Force Plates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Measurement | Acceleration, angular velocity (kinematic data) [26] | Footfall timing and location, plantar pressure distribution [24] | Three-dimensional ground reaction forces (GRF) and center of pressure (CoP) [26] |

| Primary Outputs | Stride time, cadence, joint angles (derived) [26] [25] | Stride time, step length, step width, velocity [24] | Peak force, rate of force development (RFD), impulse, postural sway metrics [27] [28] |

| Typical Environment | Lab, home, real-world [25] | Lab, clinic [24] | Lab, clinic |

| Portability | High [26] | Moderate (portable, but requires flat space) [24] | Low (typically fixed in floor) |

| Approx. Cost | $$ (varies with configuration) [24] | $$$ ($20k–$30k) [24] | $$$$ (>$150k for full motion capture integration) [24] |

| Key Advantage | Continuous monitoring in ecological settings; rich kinematic data. | Quick setup; comprehensive spatiotemporal footfall analysis. | Direct measurement of forces; high accuracy and reliability for kinetics. |

| Key Limitation | Data is derived; requires complex algorithms; sensor drift. | Limited to steps on the mat; errors with atypical foot strikes [24]. | Limited to a few steps; requires precise targeting by the user. |

Quantitative data from recent comparative studies allows for a direct performance evaluation of these systems against gold-standard references (e.g., marker-based motion capture with force plates).

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison from Validation Studies

| System Type | Example System | Validated Parameter (vs. Gold Standard) | Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable IMUs | Foot-mounted APDM IMUs | Stride Time, Cadence | MAE: 0.00–0.06 s; r = 0.92–1.00 [25] | |

| Wearable IMUs | Lumbar-mounted APDM IMUs | Gait Parameters | Consistently lower agreement than foot-mounted [25] | |

| Pressure Walkway | Tekscan Strideway | Step Length, Step Time | High agreement with motion capture (Median Error: 0.6 cm, 0.003 s) [24] | |

| Pressure Walkway | Tekscan Strideway | Step Width (Atypical FSP) | Significant errors; median error of -5.6 cm for toe-walking [24] | |

| Force Plates | Various (CMJ Test) | Peak Force, RFD | Excellent reliability (ICC = 0.86-0.93 for peak force) [27] | |

| Smartphone (IMU) | Android Smartphone | Cadence, Stride Time | Excellent agreement across various gait tasks [26] | |

| Smartphone (IMU) | Android Smartphone | Balance Variables | Poor correlation with force plate/mocap systems [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the validity and reliability of data collected with these systems, standardized protocols are essential. The following are detailed methodologies from key recent studies.

Protocol for Synchronized Multi-System Gait Validation

A 2025 study established a robust protocol for synchronously comparing wearable IMUs, a depth camera, and a pressure-sensitive walkway in a realistic clinical environment [25].

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of foot-mounted IMUs and a markerless depth camera (Azure Kinect) against a pressure-sensing walkway (ProtoKinetics Zeno) as the reference standard under real-world conditions.

- Participants: 20 older adults (mean age 70.1 ± 9.5 years), including individuals using walking aids.

- Setup and Synchronization:

- Reference System: ProtoKinetics Zeno walkway.

- Test Systems: APDM IMUs (on both feet and lumbar vertebra) and an Azure Kinect depth camera.

- Synchronization: A custom hardware-based system achieved millisecond-level temporal alignment across all three sensing platforms, a critical improvement over previous studies.

- Gait Tasks:

- Single-Task Walking: Straight-line walking at a self-selected pace.

- Dual-Task Walking: Walking while simultaneously performing a serial subtraction task (counting backward from 80 by 7). This is used to assess cognitive load effects on gait.

- Data Analysis: Eleven gait parameters were extracted. Agreement was assessed using Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Pearson correlation (r), and Bland-Altman analysis.

Protocol for Force Plate Strength Assessment (ASH Test)

A 2025 study on baseball players provides a exemplar protocol for using force plates in upper-body strength profiling [27].

- Objective: To compare peak force and early rate of force development (RFD) at three shoulder abduction angles in the Athletic Shoulder (ASH) test and assess their reliability.

- Participants: 17 elite male baseball players.

- Equipment: ForceDecks force plate system sampling at 1000 Hz.

- Test Positions: Three standardized isometric positions were tested in a prone position using the dominant arm:

- ISO-I: 180° of shoulder abduction.

- ISO-Y: 135° of shoulder abduction.

- ISO-T: 90° of shoulder abduction.

- Procedure:

- Each athlete performed three maximal isometric contractions in each position.

- Standardized verbal instructions were given to ensure consistent effort and technique.

- Data Processing: Force-time data were filtered and analyzed for peak force and early RFD (defined as the change in force within the first 100 milliseconds of contraction). Reliability was assessed via intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and coefficients of variation (CoV).

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data integration pathways for a multi-system gait analysis experiment, as described in the synchronized validation protocol [25].

Multi-System Gait Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Solutions for Biomechanical Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Force Plate System | Measures ground reaction forces and center of pressure for kinetic analysis. | Used in the ASH test for profiling shoulder strength in athletes [27]. |

| Pressure-Sensitive Walkway | Captures spatiotemporal gait parameters and foot pressure distribution. | The Tekscan Strideway provides a portable alternative to motion capture for step analysis [24]. |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Captures linear acceleration and angular velocity for kinematic analysis outside the lab. | Foot-mounted IMUs show highest accuracy for gait parameter extraction [25]. |

| Motion Capture System (Gold Standard) | Provides high-accuracy, millimeter-accurate 3D kinematic data using reflective markers and cameras. | Serves as the reference for validating new systems [24]. |

| Data Synchronization Hardware | Enables millisecond-level temporal alignment of data from multiple independent systems. | Critical for robust multi-system validation studies [25]. |

| Protocol-Specific Software | Proprietary software for data processing, feature extraction, and report generation. | Examples include Noraxon myoPressure for force plates and MVN Analyze for IMU systems [26]. |

Wearable inertial sensors, force plates, and pressure-sensitive walkways each offer a unique set of capabilities for mechanical motion analysis. The choice of system is not a matter of identifying a single superior technology, but rather of selecting the most appropriate tool for the specific research question and context. Force plates provide unmatched kinetic reliability, pressure walkways offer efficient spatiotemporal analysis in controlled settings, and wearable IMUs enable continuous, ecologically valid monitoring in real-world environments. As the field advances, the trend is moving toward sensor fusion, where the synchronized use of these systems, as demonstrated in recent studies, provides a more comprehensive and powerful analytical framework for understanding human movement.

The field of human movement analysis has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from a discipline confined to specialized laboratories to one that embraces real-world, accessible assessment. This shift represents a fundamental change in both capability and philosophy, driven by technological advancements and a growing demand for ecologically valid data. Where motion analysis once required complex, expensive optical systems in highly controlled environments, new technologies now enable precise measurement in the very environments where athletes perform and patients rehabilitate.

This transition is particularly evident in gait analysis, where the longstanding gold standard of marker-based optical motion capture is being complemented—and in some applications supplanted—by markerless computer vision and inertial measurement systems. The implications extend beyond mere convenience, touching upon the core of how researchers, clinicians, and sports professionals capture, interpret, and apply biomechanical data. This guide objectively examines this technological evolution, comparing system performance through experimental data and exploring its impact on research and clinical practice.

The Established Gold Standard: Laboratory-Based Motion Capture

For decades, optical marker-based motion capture systems have represented the undisputed reference standard for biomechanical research and clinical gait analysis.

Technology and Workflow

These systems, including established platforms like Vicon and Qualisys, operate on a fundamental principle: using multiple synchronized infrared cameras to track reflective markers placed on specific anatomical landmarks [29] [30]. Through triangulation algorithms, they reconstruct three-dimensional marker positions with exceptional precision. The typical experimental protocol involves a complex, multi-stage process:

- Laboratory Setup: Requiring a dedicated, controlled space with specific lighting conditions and calibrated camera arrangements [29].

- Subject Preparation: Involving precise marker placement on bony landmarks by trained personnel, often requiring tight-fitting clothing [31] [30].

- System Calibration: A necessary pre-data collection phase ensuring sub-millimeter measurement accuracy [29].

- Data Collection & Processing: Capturing movement trials and processing data through biomechanical modeling software to derive kinematic and kinetic parameters [30].

Performance and Limitations

The dominance of optical systems is rooted in their validated performance, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Traditional Optical Marker-Based Systems

| Metric | Reported Performance | Context & Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Positional Error | < 0.2 mm | Sub-millimeter accuracy under optimal lab conditions | [29] |

| Dynamic Positional Error | < 2 mm | Can be as low as 0.3 mm depending on setup | [22] [29] |

| Key Strength | Gold-standard accuracy; compatibility with force plates/EMG | Ideal for controlled lab-based research | [22] |

| Primary Limitations | High cost, lengthy setup, marker occlusion, ecological validity | Limited suitability for real-world, multi-sport environments | [22] [31] [29] |

Despite their precision, these systems face significant practical constraints. The requirement for controlled environments limits ecological validity, as movement in a lab may not reflect natural performance [29]. Setup and calibration are time-consuming (30-60 minutes), and marker placement can alter natural movement patterns or be impractical for certain populations [31] [29]. Furthermore, the high cost of these systems often places them beyond the reach of smaller clinics or sports teams [29].

The Driving Forces for Change

The transition toward more accessible analysis has been driven by several convergent factors that highlighted the limitations of traditional lab-bound systems.

Demand for Ecological Validity: Researchers and coaches recognized that data collected in sterile laboratory environments often failed to capture the complexities of movement in real-world settings, such as on the sports field, in workplaces, or during activities of daily living [22] [29]. This drove the need for technologies that could provide data-driven insights in the actual environments where people move and perform.

The Need for Scalability and Accessibility: The high cost and technical complexity of optical systems restricted their use to well-funded institutions [30]. This created a significant barrier for widespread implementation in routine clinical practice, smaller sports organizations, and larger-scale epidemiological studies, fueling the development of simpler, more cost-effective solutions.

Technological Convergence: Advances in key enabling technologies—particularly in artificial intelligence (AI), computer vision, and miniaturized sensors—created the foundation for a new generation of motion analysis tools. The development of sophisticated pose estimation algorithms allowed for accurate markerless tracking from standard video [32] [33].

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression and interplay of these driving forces.

Emergence of Accessible Technologies

The response to these driving forces has materialized in two primary categories of accessible motion capture technologies: Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU)-based systems and markerless computer vision systems.

Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) Systems

IMU systems utilize wearable sensors containing accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers to track segment orientation and acceleration [29].

- Experimental Protocol: Sensors are securely strapped to body segments. System calibration, often involving a neutral stance or specific movements, is performed before data collection. Participants then execute the movement tasks while data is logged internally or streamed wirelessly to a base station [29].

- Performance Data: IMUs demonstrate an angular accuracy of approximately 2–8°, depending on movement complexity and calibration [22] [29]. Their strengths are portability and suitability for outdoor capture, but they can be susceptible to sensor drift and magnetic interference [22].

Markerless Computer Vision Systems

Markerless systems represent the most significant break from traditional methods, using standard cameras and AI-powered pose estimation algorithms to infer 3D human pose directly from video, eliminating the need for markers or sensors [22] [31] [33].

- Experimental Protocol: The setup involves one or more standard or depth cameras positioned around the capture volume. Participants, wearing regular clothing, perform tasks with no need for marker placement. Computer vision models like OpenPose, OpenCap, or VisionPose automatically identify body keypoints from the video frames, which are then processed into 3D kinematics [33] [30].

- Performance Data: Accuracy varies by system, movement, and joint. A 2025 review found systems like OpenCap demonstrated a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 4.1° for 3D joint angles, with higher errors in rotational planes [32] [33]. OpenPose showed excellent reliability for spatiotemporal parameters (ICCs 0.89-0.994) and good sagittal plane hip/knee angles (MAE < 5.2°), though ankle kinematics were less accurate [33]. VisionPose demonstrated ICCs exceeding 0.969 for gait parameters compared to Vicon [30].

Comparative Analysis: Performance Across Environments

Understanding the capabilities of each technology requires direct comparison across key metrics and environments. The data reveals a trade-off between the unparalleled accuracy of optical systems and the practicality, scalability, and ecological validity of newer approaches.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Motion Capture Technologies

| Feature | Optical Marker-Based | IMU-Based Systems | Markerless Computer Vision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Accuracy | < 2 mm dynamic error [22] | 2–8° joint angle error [22] | 3-15° RMSE (sagittal plane) [22] |

| Setup Time | High (30-60 mins) [29] | Moderate [29] | Low (Minimal) [22] |

| Ecological Validity | Low (Controlled Lab) | Moderate | High (Real-World) [22] |

| Key Strengths | Gold-standard accuracy [22] | Portability, outdoor use [22] | No sensors/markers, scalability [22] |

| Key Limitations | Cost, marker artifacts, lab-bound [31] | Sensor drift, magnetic interference [22] | Sensitive to lighting/occlusion [22] |

| Best For | Controlled research, clinical biomechanics [22] | Field-based load tracking [22] | Team screening, high-throughput testing [22] |

Validation in Complex and Sport-Specific Tasks

Recent studies have rigorously validated markerless systems against the gold standard in dynamic, sport-specific contexts, a critical test for real-world applicability.

A 2025 study in the Journal of Biomechanics directly compared markerless and marker-based systems during 90° change-of-direction (COD) maneuvers, a complex action relevant to sports like soccer and rugby [31]. The research found that the markerless system "provides consistent and reliable kinematic data," showing strong agreement in joint angle patterns. However, it also identified systematic differences in the magnitude of specific joint angles (e.g., ankle dorsiflexion, knee flexion), underscoring the importance of understanding system-specific characteristics when interpreting data [31].

This validation extends to clinical applications. A systematic review in Gait & Posture (2025) concluded that pose estimation algorithm-based gait analysis "offers an accessible method to detect gait abnormalities and tailor rehabilitation strategies" [32] [33]. It highlighted OpenCap's MAE of 4.1° for 3D joint angles and OpenPose's high reliability for spatiotemporal parameters, while also noting challenges like the poor accuracy of ankle kinematics and the need for further validation of rotational angles [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experiments cited in this guide rely on a suite of essential "research reagents"—the technologies, software, and analytical tools that form the backbone of modern motion analysis. Table 3 details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Motion Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Vicon Motion Systems [34] [30] | Optical Marker-Based System | Provides gold-standard 3D kinematic data for validating new technologies and high-fidelity lab research. |

| Qualisys [34] [29] | Optical Marker-Based System | Captures high-precision motion data; often integrated with force plates for comprehensive biomechanical analysis. |

| OpenPose [33] | Pose Estimation Algorithm (Software) | Provides 2D and 3D human pose estimation from video; widely used in academic research for markerless motion tracking. |

| OpenCap [32] [33] | Markerless Motion Capture Platform | Uses smartphone cameras and OpenPose to make 3D motion analysis accessible and low-cost for clinical and research settings. |

| VisionPose [30] | AI Posture Estimation Engine | Analyzes human skeletal data from images/video for 2D/3D motion analysis in commercial and clinical applications. |

| Theia3D [22] | Markerless Motion Capture Software | Uses deep learning and multi-camera video to generate biomechanics-grade data without markers, enhancing ecological validity. |

| IMU Sensors (e.g., from GaitUp, Delsys) [34] [29] | Wearable Sensor System | Enables portable, outdoor movement tracking for field-based load monitoring and longitudinal studies. |

The typical experimental workflow for a comparative validation study, as seen in the cited research, integrates these tools. The following diagram visualizes this multi-stage process.

Implications and Future Directions

The shift to accessible, real-world analysis is already having a tangible impact. In sports, departments are adopting a tiered approach, using markerless systems for routine team screening and IMUs for load tracking, while reserving optical systems for specialized research [22]. This optimizes resource allocation and provides actionable data across multiple teams.

In clinical practice, this transition enables new paradigms for intervention. The University of Utah's study on gait retraining for knee osteoarthritis used a personalized, marker-based analysis to prescribe a specific foot angle [35]. After training, participants maintained the new gait using simple biofeedback devices, resulting in significant pain relief and reduced cartilage degradation after one year [35]. This showcases a pathway where complex lab analysis personalizes an intervention that can be maintained in daily life using accessible technology.

The market reflects this trend, with the gait analysis system market projected to grow from USD 2.74 billion in 2025 to USD 5.14 billion by 2032, driven by accessibility and integration with AI and EMR systems [8].

Future progress will depend on addressing current limitations, including improving the accuracy of markerless systems for fine-grain and rotational movements, standardizing validation protocols, and developing robust data processing pipelines that integrate multi-modal data from various systems into clinically and scientifically actionable insights [22] [33] [29].

Gait analysis technologies have transitioned from specialized laboratory tools to essential systems in clinical, research, and sports settings. This evolution is driven by technological advancements and a growing recognition of gait as a critical biomarker for health. The global gait analysis system market, valued at approximately USD 200 million in 2023, is projected to reach USD 450 million by 2032, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.2% [36]. Some analyses present an even more aggressive growth trajectory, forecasting an expansion from USD 450 million in 2025 to USD 1.2 billion by 2031 [37]. This growth is underpinned by a fundamental thesis: while traditional optical systems offer gold-standard accuracy, emerging mechanical and markerless technologies provide a compelling balance of practicality, scalability, and cost-effectiveness for diverse applications. This guide objectively compares the performance of these technologies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data and economic context needed for informed evaluation.

The gait analysis market is experiencing robust growth, fueled by demographic trends, technological innovation, and expanding applications. North America currently dominates the market with a 40.3% share as of 2025, but the Asia-Pacific region is poised to be the fastest-growing market, driven by improving healthcare infrastructure and rising patient populations [8].

Primary Adoption Drivers

Aging Population and Associated Disorders: The rising prevalence of gait-related neurological and musculoskeletal disorders, such as Parkinson's disease, cerebral palsy, and arthritis, in an aging global population is a primary market driver [36]. These conditions necessitate precise diagnosis and monitoring, which modern gait analysis systems can provide.

Technological Advancements: Innovations in wearable sensors, 3D motion capture, and AI-based data analysis are enhancing the accuracy, accessibility, and efficacy of gait analysis [36]. The software segment, which accounts for the largest market share by component (45.2% in 2025), is a key beneficiary, with AI and machine learning revolutionizing data processing and insight generation [8].

Expansion into New Applications: Beyond clinical diagnostics, gait analysis is being rapidly adopted in sports performance enhancement and rehabilitation. Athletes and coaches use these systems to optimize performance and prevent injuries, while rehabilitation centers rely on them for objective progress tracking and therapy personalization [36].

Market Segment Dynamics

Table: Gait Analysis System Market Snapshot (2025 Projections)

| Segment | Leading Category | Market Share | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Type | Stationary Systems | Higher precision for clinical/research [36] | Advanced 3D motion capture and force plates [36] |

| Technology | Optical Sensors | 30.2% [8] | High precision, non-invasive nature, and versatility [8] |

| Application | Clinical Applications | Dominant share [36] | Need for accurate diagnosis of gait abnormalities [36] |

| Region | North America | 40.3% [8] | Established healthcare infrastructure and high adoption of advanced technologies [8] |

Comparative Analysis of Gait Analysis Technologies

Evaluating the performance of different gait capture technologies is crucial for selecting the appropriate system for a given research or clinical context. The following comparison is based on recent validation studies and systematic reviews.

Technology Performance Comparison

Table: Performance Metrics of Motion Capture Technologies in Gait Analysis

| Technology | Accuracy (Joint Angles) | Strengths | Limitations | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical (Marker-Based) | <2 mm dynamic error [22] | Gold-standard accuracy; High compatibility with force plates/EMG [22] [38] | High cost and setup time; Markers can alter natural movement [22] [38] | Controlled lab-based research; Clinical biomechanics [22] |

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | 2–8° [22] | Excellent portability; Suitable for indoor/outdoor capture [22] [3] | Susceptible to drift and magnetic interference [22] | Field-based load tracking; Long-term monitoring [22] [3] |

| Markerless Systems | 3–15° RMSE (sagittal); 2–9° (frontal) [22]; 5.5 ± 1.1° (monocular) [7] | High ecological validity; Minimal setup; Highly scalable [22] [38] | Sensitive to lighting/background; Less precise for fine rotations [22] | Team screening; High-throughput testing; Remote assessment [22] [7] |

| Industrial Ergonomic Focus | 2.31° ± 4.00° mean joint-angle error [38] | Feasible and scalable for field settings; Good reliability (ICC > 0.80) [38] | Less accurate than marker-based gold standards [38] | Industrial risk assessment (e.g., RULA/REBA) [38] |

Key Experimental Findings from Recent Studies

Markerless vs. Marker-Based Validity: A 2025 study in the Journal of Biomechanics evaluated a low-cost monocular markerless system (CameraHMR) against a marker-based system. It found the overall performance of the monocular system to be comparable to a established two-camera markerless system (OpenCap), with a reasonable kinematic accuracy of 5.5 ± 1.1 degrees RMSD, despite challenges in tracking ankle joints [7].

Reliability in Multi-Session Studies: The same study demonstrated promising test-retest reliability for the monocular markerless system, with an RMSD of 3.0 ± 1.0 degrees across sessions, suggesting its potential for tracking gait changes over time [7].

Industrial Application Validity: A 2025 systematic review in Sensors concluded that markerless systems demonstrate moderate-to-high accuracy for ergonomic risk assessment, with several studies reporting strong validity for predicting RULA/REBA scores (accuracy up to 89%, κ = 0.71) [38].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of gait analysis studies, a clear understanding of standardized protocols is essential. Below are detailed methodologies from key recent studies.

Protocol 1: Validation of a Monocular Markerless System

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 validity and reliability study published in the Journal of Biomechanics [7].

- Objective: To evaluate the concurrent validity and test-retest reliability of a low-cost monocular markerless system (CameraHMR) for 3D gait analysis.

- Participants: 19 healthy adults.

- Gait Tasks:

- Validity Dataset: Participants walked under four conditions: physiological gait, crouch gait, circumduction, and equinus gait.

- Reliability Dataset: A separate group of 19 participants performed physiological walking on two separate days.

- Data Collection:

- Reference System: A marker-based motion capture system (e.g., Vicon) was used as the gold standard for the validity dataset.

- Test System: The monocular markerless system (CameraHMR) was applied to single-view videos recorded during the trials.

- Data Processing:

- 3D joint kinematics were extracted from the markerless data using the SMPL (Skinned Multi-Person Linear) model and OpenSim's inverse kinematics tool.

- Waveform root mean square deviation (RMSD) was calculated against the marker-based system for validity.

- RMSD and standard error of measurement (SeM) were used to assess reliability across the two sessions.

- Key Outcome Measures: RMSD for lower body joint angles (hip, knee, ankle) in three planes.

Protocol 2: Multi-Pathology Clinical Gait Data Acquisition

This protocol is derived from a 2025 open-access data descriptor in Scientific Data that created a large inertial sensor dataset [3].

- Objective: To collect a large-scale, clinically annotated dataset of gait signals from healthy, neurological, and orthopedic cohorts using wearable sensors.

- Participants: 260 participants, including healthy individuals and patients with various neurological (Parkinson's disease, stroke, peripheral neuropathy) and orthopedic (hip/knee osteoarthritis, ACL injury) conditions.

- Sensor Setup: Four inertial measurement units (IMUs) were placed on the head, lower back (L4/L5), and the dorsal part of each foot.

- Gait Task: A standardized 10-meter walk test protocol was used:

- Stand still for a few seconds.

- Walk 10 meters at a comfortable pace.

- Turn 180 degrees.

- Walk back 10 meters.

- Stand still again at the finish line.

- Data Recording: Data were recorded at a sampling rate of 100 Hz using synchronized IMUs (XSens or Technoconcept).

- Clinical Annotation: For each patient, the relevant clinical score (e.g., Hoehn and Yahr for Parkinson's, Berg Balance Scale for stroke) was recorded on the day of assessment to grade disease severity [3].

Diagram: Clinical Gait Data Acquisition Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate technology platform is a fundamental decision in gait research. The following table details key vendors and system types, reflecting the current market landscape [34].

Table: Key Gait Analysis Research Reagents and Platforms

| Vendor / Solution | Technology Type | Primary Function | Typical Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vicon [34] | Optical (Marker-Based) | High-precision motion capture | Clinical and research biomechanics; Gold-standard validation studies |

| Qualisys [34] | Optical (Marker-Based) | Optical motion capture with high-speed data acquisition | Sports science; Advanced biomechanics research |

| BTS Bioengineering [34] | Hybrid (Optical + Force Plates) | Combines motion analysis with force measurement | Comprehensive gait lab analysis; Integrated kinetic and kinematic studies |

| Xsens [3] | Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Wireless wearable motion tracking | Field-based studies; Outdoor and long-duration monitoring |

| OptoGait [34] | Portable System (Optical) | Portable, easy-to-use gait analysis | Clinical screenings; Sports facility assessments |

| Zebris [34] | Sensor-Based | Sensor-based systems with real-time feedback | Rehabilitation therapy; Outpatient clinical monitoring |

| CameraHMR (Monocular) [7] | Markerless (Computer Vision) | 3D pose estimation from a single camera | Low-cost, accessible gait assessment; Remote and home-based settings |

| OpenCap [7] | Markerless (Computer Vision) | 3D kinematics using at least two smartphones | Accessible biomechanics; Population-level studies |

Economic and Operational Considerations

Beyond technical performance, the economic viability and operational practicality of gait analysis technologies are critical for their adoption, especially in resource-constrained environments.

Cost-Benefit and Integration Landscape

The High-Cost Barrier: The high cost of advanced stationary systems, particularly those integrated with force plates and EMG, remains a significant barrier to adoption, especially in emerging markets and smaller facilities [36]. This has accelerated the development of more cost-effective solutions, such as portable and markerless systems.

The Portability Advantage: Portable gait analysis systems have gained significant traction due to their flexibility, ease of use, and cost-effectiveness. Their ability to be deployed in homes, clinics, and outdoor environments supports the growing trends of home healthcare and remote monitoring, enhancing patient compliance and outcomes [36].

Integration with Healthcare Workflows: A key operational trend is the integration of gait analysis software with Electronic Medical Record (EMR) systems. This interoperability, facilitated by standards like HL7 and FHIR, streamlines clinical workflows and embeds gait assessment data into routine patient care, thereby increasing its appeal in hospital settings [8].

Diagram: Gait Analysis System Selection Logic

The gait analysis technology landscape is dynamic and increasingly diverse. The core thesis—evaluating optical versus mechanical and emerging systems—reveals a clear trajectory: the market is expanding beyond the gold-standard laboratory optical system towards a tiered ecosystem where technology choice is dictated by a balance of accuracy, practicality, and cost.

Optical marker-based systems will remain indispensable for validation studies and high-precision laboratory research. However, the future of widespread clinical adoption, routine sports screening, long-term monitoring, and remote healthcare lies with the scalable and cost-effective profiles of IMUs and markerless systems. The integration of AI and cloud computing will further democratize access to sophisticated biomechanical analysis, embedding gait assessment more deeply into preventative medicine, rehabilitation, and performance optimization. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolution offers unprecedented opportunities to capture ecologically valid gait data at scale, promising richer datasets for biomarker discovery and therapeutic evaluation.

Implementation Strategies and Domain-Specific Applications in Research and Clinic

This guide provides an objective comparison of optical and mechanical gait analysis systems, focusing on their deployment in clinical and research settings. It is structured to support the evaluation of these technologies within a broader thesis on gait analysis methodologies.

Optical motion capture systems are the established gold standard for gait analysis, using infrared cameras and reflective markers to provide highly accurate 3D kinematic data. In contrast, mechanical systems based on wearable inertial sensors offer portability for real-world gait assessment outside the laboratory [39].

The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics of these two system types based on current literature and market offerings.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Gait Analysis System Types

| Feature | Optical Motion Capture (Mechanical Gait Labs) | Wearable Sensor Systems (Mechanical Setups) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Technology | 3D optical capture with infrared cameras & reflective markers [39] | Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) - accelerometers & gyroscopes [39] |

| Key Measured Parameters | Highly accurate 3D kinematics (joint angles, trajectories), often integrated with kinetic data from force plates [39] | Gait speed, cadence, step time, trunk accelerations, and estimated joint angles [39] |

| Typical Accuracy & Data Fidelity | Considered the gold standard for kinematic accuracy in controlled environments [39] [34] | High accuracy for temporal-spatial parameters; kinematic accuracy can be lower than optical systems [34] |

| Portability & Setup Time | Low portability; requires a dedicated lab space. Setup and calibration are time-consuming [39] [34] | High portability; can be used in clinics, homes, or outdoors. Setup is typically rapid [39] [34] |

| Best Application Context | High-precision research and clinical diagnostics where laboratory control is possible and necessary [39] [34] | Sports performance, rehabilitation monitoring, long-term patient assessment, and real-world gait analysis [39] [34] |

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

A critical step in deploying these systems is validating their performance under various experimental conditions. The following protocols detail key methodologies cited in recent research.

Protocol: Evaluating Overhead Support Systems

Objective: To determine the effect of an overhead support harness system on gait kinematics and kinetics during overground versus treadmill walking [40].

- Participants: 15 healthy young adults [40].