Optical vs. Electrochemical Biosensors: A 2025 Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research and Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of optical and electrochemical biosensors, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Optical vs. Electrochemical Biosensors: A 2025 Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of optical and electrochemical biosensors, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles and transduction mechanisms underlying both sensor types, including recent innovations such as AI-integration and nanomaterial enhancements. The review methodically examines their applications in critical areas like disease diagnostics, therapeutic drug monitoring, and pathogen detection. It further addresses key challenges in sensor optimization, reliability, and commercialization, culminating in a direct, evidence-based comparison of their analytical performance, usability, and suitability for point-of-care and clinical settings. The synthesis aims to guide the selection and development of biosensor technologies for advanced biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles and Transduction Mechanisms: Understanding the Basis of Biosensor Technology

Biosensors represent a convergence of biological recognition and physicochemical detection, forming critical analytical tools for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. These devices integrate biological elements with transducers to produce signals proportional to specific analytes, enabling applications ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring [1]. The fundamental architecture of any biosensor comprises three essential components: a bioreceptor that specifically recognizes the target analyte, a transducer that converts the biological event into a measurable signal, and a readout system that processes and displays the results [2]. Understanding this architecture is paramount for selecting appropriate biosensing technologies for specific research applications.

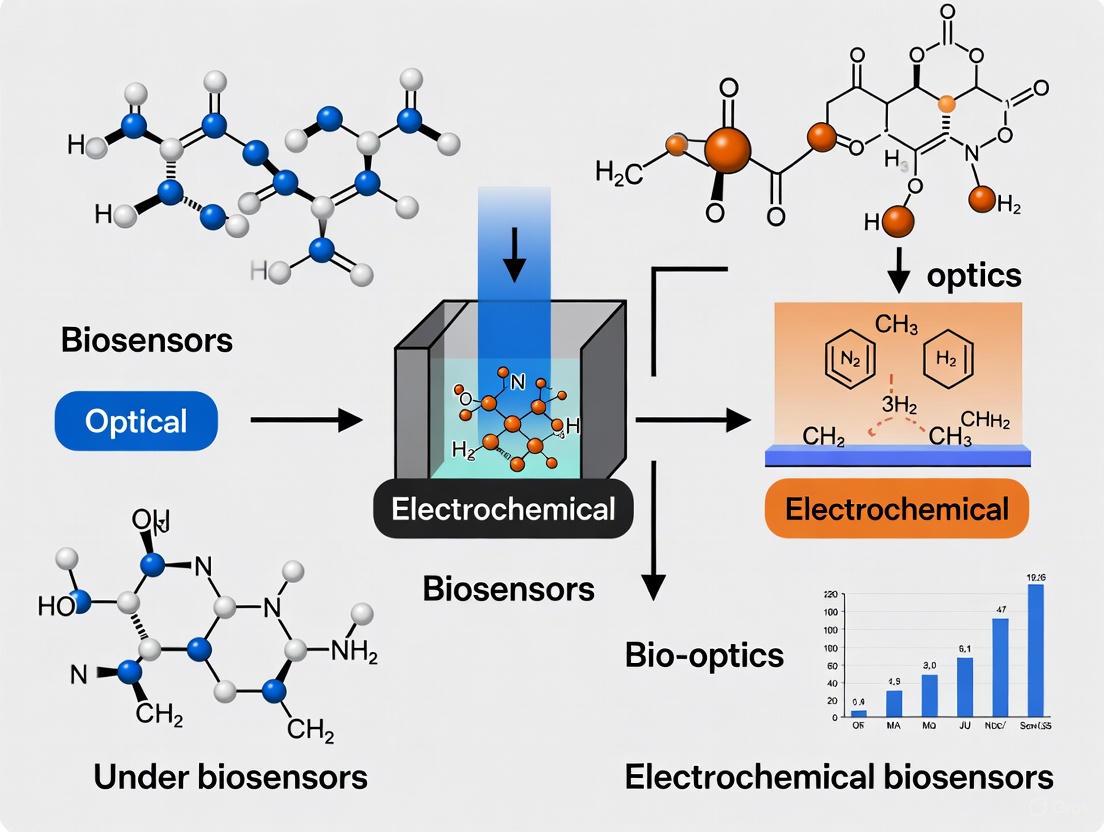

Among the diverse biosensor classifications, optical and electrochemical platforms have emerged as the most prominent technologies in research and commercial environments. Optical biosensors detect analytes by measuring changes in light properties, while electrochemical biosensors monitor electrical signals resulting from biochemical reactions [1]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these technologies, focusing on their operational principles, performance characteristics, and implementation protocols to inform strategic selection for research and development applications.

Core Architectural Components of a Biosensor

Bioreceptors: The Recognition Elements

Bioreceptors serve as the molecular recognition components of biosensors, providing specificity for target analytes through biological binding events. These elements include enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids, whole cells, and aptamers designed to interact specifically with the target of interest [3] [2]. The selection of appropriate bioreceptors depends on the target analyte and required specificity, with immobilization techniques critical for maintaining biological activity while ensuring stability on the transducer surface [4].

Transducers: The Signal Conversion System

Transducers form the core of the signal conversion mechanism, transforming the biological recognition event into a quantifiable output. They are categorized based on their transduction principles, with optical and electrochemical representing the two primary approaches [2]. Optical transducers monitor changes in light properties including absorbance, fluorescence, reflectance, or refractive index [1] [5]. Electrochemical transducers detect electrical changes—current (amperometric), potential (potentiometric), or impedance (impedimetric)—resulting from biochemical reactions [6] [3].

Readout Systems: Data Processing and Display

Readout systems comprise the electronic components that amplify, process, and present the transducer signal in a user-interpretable format [3]. These systems have evolved significantly with advancements in miniaturization and wireless technologies, enabling portable and wearable form factors for point-of-care testing and continuous monitoring applications [2]. Modern readout systems often integrate with smartphones or cloud platforms for data analysis and storage, facilitating real-time health monitoring and remote patient management [6].

Comparative Analysis: Optical vs. Electrochemical Biosensors

The table below summarizes the key technical differences between optical and electrochemical biosensor technologies.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Optical and Electrochemical Biosensors

| Parameter | Optical Biosensors | Electrochemical Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Mechanism | Interaction of light with target molecule [1] | Measurement of electrical signals [1] |

| Transducer Element | Light [1] | Electrodes [1] |

| Working Principle | Changes in optical properties (absorbance, fluorescence, refractive index) [1] [5] | Electrochemical reactions (redox reactions) [1] [6] |

| Detection Dynamic Range | Wide [1] | Limited [1] |

| Sensitivity | High (particularly SPR) [5] [7] | High [6] [7] |

| Response Time | Slow (minutes) [1] | Fast (seconds) [1] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Excellent (allows simultaneous multi-analyte detection) [1] | Limited [1] |

| Sample Requirement | Often requires purified samples [1] | Works with complex or crude samples [1] |

| Portability | Generally bulky [1] | Compact and portable [1] [7] |

| Cost | Higher (specialized optics) [1] [7] | Lower (simple setup) [1] [7] |

| Lifetime | Up to several years [1] | Up to several minutes (some types) [1] |

Transducer Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Optical Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms

Optical biosensors primarily utilize evanescent field effects in close proximity to the sensor surface. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), the predominant optical technique, occurs when polarized light hits a metal (typically gold) surface at a specific interface, generating electron charge oscillations called surface plasmons [5]. Binding events alter the refractive index near the surface, changing the resonance conditions and producing detectable signals [5]. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) employs metallic nanostructures with unique optical properties that respond to local dielectric environmental changes [5].

Electrochemical Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms

Electrochemical biosensors function through electron transfer mechanisms during biochemical reactions. When target analytes interact with immobilized bioreceptors, biochemical reactions produce measurable electrical signals through amperometric (current), potentiometric (potential), or impedimetric (impedance) techniques [6] [3]. These systems typically employ a three-electrode configuration: working electrode (sensing), reference electrode (stable potential reference), and counter electrode (completing the circuit) [3].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Validation

Experimental Protocol: Electrochemical Biosensor for Pathogen Detection

Recent research demonstrates the development of a high-performance electrochemical biosensor for Escherichia coli detection, achieving exceptional sensitivity [4]. The following protocol outlines the key experimental steps:

Sensor Fabrication:

- Synthesis of Mn-doped ZIF-67 (Co/Mn ZIF): Prepare zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-67) with manganese doping at varying ratios (10:1, 5:1, 2:1, and 1:1 Co:Mn) to enhance electron transfer properties [4].

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast the synthesized Co/Mn ZIF composite onto the working electrode surface (typically glassy carbon or screen-printed carbon electrodes).

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Conjugate anti-O specific antibodies to the Co/Mn ZIF-modified electrode surface using EDC-NHS carbodiimide chemistry to ensure specific binding to the O-polysaccharide region of E. coli [4].

Measurement Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Spike E. coli cultures at varying concentrations (10–1010 CFU mL–1) in appropriate matrices (buffer or tap water).

- Electrochemical Measurement: Employ electrochemical techniques such as cyclic voltammetry (CV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) using a standard three-electrode system.

- Signal Detection: Monitor changes in electron transfer resistance or redox current upon bacterial binding to the functionalized electrode surface.

- Data Analysis: Quantify E. coli concentration from the calibration curve of electrical signal versus bacterial concentration [4].

Performance Metrics:

- Linear Detection Range: 10 to 1010 CFU mL–1

- Limit of Detection: 1 CFU mL–1

- Selectivity: Successfully discriminates non-target bacteria (Salmonella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus)

- Stability: Maintains >80% sensitivity over 5 weeks

- Real-sample Recovery: 93.10–107.52% recovery in tap water samples [4]

Experimental Protocol: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensing

SPR represents the most common optical biosensing method, particularly valuable for characterizing biomolecular interactions in real-time without labeling [5].

Sensor Preparation:

- Chip Functionalization: Immobilize the ligand (e.g., antibody, receptor) on the gold sensor chip surface using appropriate chemistry (commonly NHS-ester coupling on carboxymethylated dextran matrices).

- System Priming: Prime the SPR instrument with running buffer to establish a stable baseline signal.

Interaction Analysis:

- Analyte Injection: Introduce the analyte solution over the sensor surface using continuous flow at controlled rates.

- Real-time Monitoring: Measure the shift in resonance angle (response units) as analyte binds to the immobilized ligand.

- Dissociation Phase: Replace analyte solution with running buffer to monitor complex dissociation.

- Surface Regeneration: Apply a regeneration solution (typically mild acid or base) to remove bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand.

Data Processing:

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract signals from reference flow cells to account for bulk refractive index changes and non-specific binding.

- Kinetic Analysis: Fit the association and dissociation phases to appropriate binding models (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir binding) to determine kinetic rate constants (kon, koff) [5].

- Affinity Calculation: Derive equilibrium constants (KD = koff/kon) from kinetic parameters.

Performance Characteristics:

- Detection Limit: Varies by system and application (e.g., 0.5 nM for FK506-FKBP12 interaction in SPR imaging) [5]

- Throughput: SPR imaging enables high-throughput analysis of multiple interactions simultaneously [5]

- Label-free Operation: Enables monitoring of native molecular interactions without fluorescent or radioactive labels

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines key reagents and materials essential for implementing biosensor research protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIF-67) | Porous material with large surface area for enhanced electron transfer and bioreceptor immobilization [4] | Electrochemical biosensor electrode modification |

| Mn-doped ZIF-67 | Bimetallic framework with enhanced conductivity and surface reactivity for improved sensitivity [4] | High-performance pathogen detection |

| Anti-O Antibody | Bioreceptor specific to O-polysaccharide region of E. coli for selective pathogen recognition [4] | Bacterial detection assays |

| EDC-NHS Chemistry | Carbodiimide crosslinking for covalent immobilization of biomolecules on sensor surfaces [4] | Antibody conjugation to transducer surfaces |

| SPR Gold Chips | Sensor substrates with functionalized gold surfaces for plasmon resonance generation [5] | Optical biosensing platforms |

| Carboxymethylated Dextran | Hydrogel matrix for biomolecule immobilization on SPR chips via amine coupling [5] | Ligand attachment in SPR studies |

| Screen-printed Electrodes | Disposable electrode systems for portable electrochemical sensing [6] | Point-of-care biosensor development |

Optical and electrochemical biosensors offer complementary strengths for research and diagnostic applications. Optical platforms, particularly SPR-based systems, provide superior sensitivity, real-time monitoring, and multiplexing capabilities ideal for detailed biomolecular interaction analysis in laboratory settings [5]. Electrochemical systems excel in portability, cost-effectiveness, and operational simplicity, making them suitable for point-of-care testing and field applications [6] [7].

The architectural differences between these technologies dictate their appropriate application domains. Optical biosensors remain the gold standard for mechanistic studies of molecular interactions in drug development and basic research [5]. Electrochemical biosensors demonstrate superior performance for detection of low analyte concentrations in complex samples, with ongoing advancements in nanomaterials and bioreceptor engineering further enhancing their capabilities [6] [4].

Selection between optical and electrochemical platforms should consider the specific research requirements including sensitivity needs, sample matrix, required throughput, portability constraints, and available resources. Future developments in both technologies will likely focus on increased miniaturization, multiplexing capabilities, and integration with wearable platforms for continuous monitoring applications [2].

Electrochemical biosensors represent a cornerstone of modern analytical science, offering powerful tools for researchers and drug development professionals. These devices transform biological interactions into quantifiable electrical signals, providing a platform for detecting everything from simple ions to complex proteins and nucleic acids. Within this domain, three principal techniques—amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric sensing—form the essential toolkit. This guide provides a objective comparison of these techniques, framing them within the broader research context of electrochemical versus optical biosensors. It delivers structured performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential resource information to inform experimental design and technology selection in scientific and pharmaceutical environments.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Electrochemical biosensors function by integrating a biological recognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, aptamer) with a physicochemical transducer that outputs an electrical signal [8]. The classification into amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric types is defined by the nature of this output signal.

- Amperometric Sensors measure the current generated by the electrochemical oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species at a constant applied potential. The resulting current is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte [8]. A classic and widespread application is the glucose meter, which uses the enzyme glucose oxidase to generate a measurable current [9].

- Potentiometric Sensors measure the accumulation of a potential (voltage) at the working electrode relative to a reference electrode under conditions of zero current. This potential difference correlates to the logarithm of the analyte's activity or concentration, as described by the Nernst equation [8]. Common examples include ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) for pH, sodium, potassium, and lead detection [8] [10].

- Impedimetric Sensors measure the electrical impedance of the electrode-solution interface. The binding of a target analyte alters the interfacial properties, changing the charge transfer resistance (in faradaic systems) or the double-layer capacitance (in non-faradaic systems). These changes are typically monitored using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [11].

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics and performance metrics of these three sensing modalities.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Electrochemical Sensing Techniques

| Feature | Amperometric | Potentiometric | Impedimetric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Current | Potential (Voltage) | Impedance (Resistance & Capacitance) |

| Theoretical Basis | Cottrell Equation [8] | Nernst Equation [8] | Nyquist/ Bode Plots (EIS) [11] |

| Typical LoD | Picomoles and above [8] | Micromolar (µM) to Nanomolar (nM) [11] | Low, down to femtomolar (fM) for some targets [11] |

| Key Advantage | High accuracy and sensitivity [8] | Simplicity, low cost, robustness [8] [11] | Label-free, real-time detection, low LoD [11] |

| Key Disadvantage | Dependence on enzymes/redox mediators, higher LoD than impedimetric [11] | Limited to ion sensing/complex biological targets, slower response [11] | Can be sensitive to non-specific binding, data analysis complexity |

| Common Applications | Glucose monitoring, environmental monitoring [9] [8] | pH sensing, ion detection (e.g., Pb²⁺ [10]), wearable sweat sensors [12] [8] | Detection of proteins, pathogens, DNA, and whole cells [11] |

When compared to optical biosensors in the context of point-of-care applications, electrochemical platforms generally offer advantages in cost, portability, and ease of miniaturization [9]. Optical biosensors, while often exhibiting exceptional sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities, can be limited by higher cost, more complex instrumentation, and lower portability [13] [9].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

To illustrate the practical application of these techniques, this section details representative experimental protocols for each sensor type, based on recent research.

Amperometric Sensing: Glucose Detection

The glucose meter is a quintessential example of an amperometric biosensor. The experimental workflow involves a bio-recognition layer that triggers a redox reaction, generating a measurable current.

Protocol:

- Electrode Preparation: A screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) is commonly used. The working electrode is modified with the enzyme glucose oxidase (GOx).

- Reaction Principle: Glucose in the sample is oxidized by GOx, producing gluconolactone and reducing the enzyme's FAD cofactor to FADH₂. The enzyme is then regenerated by a mediator (e.g., ferricyanide, ferrocene derivatives), which is oxidized at the electrode surface [9].

- Measurement: A constant potential is applied between the working and reference electrodes. The oxidation of the mediator generates a current that is directly proportional to the glucose concentration in the sample.

Performance Data: This well-established technology offers high accuracy and rapid response, making it suitable for routine clinical and personal use.

Potentiometric Sensing: Lead Ion (Pb²⁺) Detection

A recent study developed a high-sensitivity potentiometric sensor for detecting toxic lead ions (Pb²⁺) in aqueous samples using Thiophanate-methyl (TPM) as an ionophore [10].

Protocol:

- Sensor Fabrication: The sensor membrane was prepared by mixing the TPM ionophore with poly (vinyl chloride) (PVC) as a matrix, along with plasticizers (dibutyl phthalate or bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate) and additives. This membrane was then coated on a solid electrode surface.

- Measurement: The potential difference between the TPM-modified working electrode and a separate reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) is measured under zero-current conditions in solutions containing varying concentrations of Pb²⁺.

- Calibration: The measured potential is plotted against the logarithm of the Pb²⁺ concentration to generate a calibration curve.

Performance Data [10]:

- Linear Range: The sensor showed a wide linear response to Pb²⁺ concentration.

- Limit of Detection (LOD): 1.5 × 10⁻⁸ M

- Selectivity: Exhibited high selectivity for Pb²⁺ over other interfering ions (e.g., Zn²⁺, Cd²⁺, Cu²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺), attributed to the specific binding properties of the TPM ionophore.

- Lifetime: The sensor maintained stable performance for over 120 days.

Impedimetric Sensing: Protein Detection

Impedimetric biosensors are highly effective for label-free detection of proteins. A representative protocol involves an antibody-functionalized gold electrode for detecting a specific antigen.

Protocol:

- Surface Functionalization: A gold working electrode is cleaned and modified with a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) of thiolated molecules. Antibodies specific to the target protein are then immobilized onto this SAM surface.

- Faradaic EIS Measurement: Measurements are performed in a solution containing a redox probe, typically [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻. A small amplitude AC voltage (e.g., 5-10 mV) is applied over a range of frequencies (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz).

- Target Binding and Detection: Before analyte introduction, a baseline EIS spectrum is recorded. The binding of the target antigen to the immobilized antibody hinders the electron transfer of the redox probe to the electrode surface, leading to an increase in the charge transfer resistance (Rct). This change in Rct is quantitatively measured.

Performance Data (Exemplar) [11]: Advanced impedimetric biosensors using microelectrodes and nanomaterials have demonstrated detection of protein biomarkers like cardiac troponin I (cTnI) with limits of detection in the femtomolar (fM) range, highlighting their exceptional sensitivity.

The workflow for a faradaic impedimetric biosensor, common in protein detection, is visualized below.

Flowchart of a Faradaic EIS Experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of electrochemical sensing requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details key components and their functions based on the protocols discussed.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Low-cost, disposable, mass-producible platforms for easy experimentation. | Amperometric glucose test strips [9]. |

| Gold (Au) & Platinum (Pt) Electrodes | Provide highly conductive, inert, and easily functionalizable surfaces. | Impedimetric biosensors; Au for thiol-based antibody/aptamer immobilization [11]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Polymer membranes containing an ionophore that selectively binds target ions. | Potentiometric sensors for Pb²⁺ (TPM ionophore [10]), pH, K⁺, Na⁺. |

| Redox Probes (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Mediate electron transfer in faradaic impedimetric and some amperometric sensors. | Measuring charge transfer resistance (Rct) in EIS [11]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) | Act as biological recognition elements that catalyze specific redox reactions. | Amperometric glucose biosensors [9]. |

| Biorecognition Elements (Antibodies, Aptamers) | Provide high specificity and selectivity for binding target analytes. | Impedimetric and amperometric detection of proteins, pathogens, or other biomarkers [11]. |

| Nafion | A cationic polymer used as a protective top layer to facilitate selective cation transport and enhance sensor stability. | Used in wearable potentiometric sensors to achieve 2-week stability [12]. |

| PEDOT:PSS/Graphene Composite | Serves as an effective ion-to-charge transducer material, enhancing sensitivity and stability. | Used in potentiometric sensors to achieve super-Nernstian response and low drift [12]. |

Amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric sensors each occupy a unique and vital niche in the electrochemical realm. Amperometric sensors offer robust, enzyme-driven quantification. Potentiometric sensors provide simple and cost-effective ion monitoring. Impedimetric sensors deliver high-sensitivity, label-free detection for a broad range of biological targets. The choice of technique is not a matter of identifying a universal "best" option, but rather of aligning the sensor's characteristics—its operational principle, sensitivity, cost, and complexity—with the specific requirements of the analytical problem. This objective comparison underscores that ongoing innovation, particularly through nanomaterials and advanced biorecognition elements, continues to push the performance boundaries of all three techniques, solidifying their collective importance in scientific research and drug development.

The rapid and accurate detection of biological and chemical analytes is fundamental to advancements in medical diagnostics, drug development, and environmental monitoring [14] [15]. Biosensors, which combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical detector, are at the forefront of this analytical revolution. While electrochemical biosensors represent a significant portion of the market, optical biosensors offer distinct advantages, including rapid analysis, portability, high sensitivity, and the potential for multiplexing capabilities [16]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of four principal optical detection techniques—Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Fluorescence, Colorimetric, and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS)—framed within the broader context of optical versus electrochemical sensing approaches. The objective is to offer researchers and drug development professionals a clear, data-driven overview of these technologies to inform experimental design and platform selection.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Performance

Each optical technique operates on a unique physical principle, which directly influences its performance characteristics, advantages, and limitations. The table below summarizes the core attributes and performance metrics of these four optical methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Optical Biosensing Modalities

| Detection Method | Core Principle | Typical LOD | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR | Measures refractive index change from biomolecular binding on a metal surface [17]. | ~0.4 pg/mL (for Influenza H1N1) [15] | Label-free, real-time kinetics, high sensitivity. | Complex instrumentation, bulk refractive index sensitivity. |

| Fluorescence | Detects light emission from labels upon excitation [16]. | 18.50 aM (for miRNA) [18] | Extremely high sensitivity, multiplexing capability, versatile. | Requires fluorescent labels, potential photobleaching. |

| Colorimetric | Measures visual color change from analyte-probe interaction [16]. | 10 CFU/mL (for S. aureus) [16] | Simple, low-cost, naked-eye readout, ideal for POC. | Lower sensitivity than other methods, qualitative without instrumentation. |

| SERS | Enhances Raman signal of molecules on nanoscale metallic surfaces [17] [18]. | Single-molecule level potential [18] | "Fingerprint" specificity, extremely high sensitivity, multiplex potential. | Substrate reproducibility, complex substrate fabrication. |

Synergy with Electrochemical Sensing

A notable trend in biosensing is the development of dual-mode platforms that combine the strengths of optical and electrochemical methods. For instance, SERS-electrochemical (EC) dual-mode biosensors integrate the high sensitivity and molecular fingerprinting of SERS with the rapid response and ease of miniaturization of electrochemical detection [18]. Similarly, electrochemical SPR (ESPR) combines the label-free, real-time kinetic data of SPR with electrochemical readouts, improving reliability and enabling a more comprehensive analysis of binding events [19] [20]. These hybrid approaches are particularly powerful for detecting challenging biomarkers like cancer-related miRNAs at ultralow concentrations [18].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The practical implementation of each biosensing technique involves distinct experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in recent literature, illustrating the standard workflows.

SERS/EC Dual-Mode Biosensor for miRNA Detection

This protocol, adapted from Jin et al. (2025), outlines the steps for creating an ultrasensitive biosensor for cancer-related miRNA-106a [18].

- Core Principle: The sensor uses a DNA walker mechanism on a silver nanorods (AgNRs) electrode. Target miRNA triggers a cyclic cleavage reaction, releasing numerous signal probes.

- Key Reagents:

- AgNRs-based Sensing Electrode: SERS-active and electrochemically active substrate.

- MoS₂-based Dual-Mode (DM) Tags: Carrier for signal molecules (Methylene Blue).

- DNAzyme & Walker Strands: Catalyze the target-dependent cleavage reaction.

- Methylene Blue (MB): Acts as both a Raman reporter and an electrochemical probe.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Sensor Preparation: The AgNRs electrode is functionalized with DNA walker (LW) strands. MoS₂ nanosheets are loaded with MB and reporter DNA (rDNA) to form DM tags.

- Target Recognition: Introducing target miR-106a initiates the DNA walker process. The DNAzyme is activated and cleaves the substrate strands on the electrode, releasing a short trigger DNA (T).

- Signal Amplification & Detection: The released trigger DNA (T) hybridizes with the DM tags, detaching the MB-loaded rDNA. This leads to a decrease in both the SERS and electrochemical signals of MB, allowing for dual-mode quantification of the target.

Fluorescence Biosensor for Available Lead Detection

This protocol, based on Chen et al. (2023), describes a method for ultrasensitive detection of bioavailable lead ions (Pb²⁺) using DNAzyme and hairpin assembly [21].

- Core Principle: The sensor employs Pb²⁺-specific DNAzyme for recognition. The recognition event triggers a cascade of hairpin assembly reactions, producing a Y-shaped scaffold with active DNAzymes that cleave a fluorescent reporter for signal amplification.

- Key Reagents:

- 8-17 DNAzyme: Comprises an enzyme strand and a substrate strand with a ribonucleotide (rA) cleavage site.

- Hairpin Probes (H1, H2, H3, H4): H4 is labeled with a fluorophore (FAM) and a quencher (BHQ).

- Magnetic Beads: For separation and purification.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Target Recognition & Cleavage: Pb²⁺ recognizes the DNAzyme and cleaves its substrate strand at the rA site.

- Trigger Release: The cleavage releases a trigger DNA strand (T).

- Hairpin Assembly Cascade: The trigger T initiates a toehold-mediated strand displacement reaction, self-assembling hairpins H1, H2, and H3 into a Y-shaped structure (H1-H2-H3).

- Signal Amplification & Output: The H1-H2-H3 complex contains multiple active Mg²⁺-DNAzymes. These DNAzymes repeatedly cleave the fluorogenic substrate H4, separating the FAM fluorophore from the BHQ quencher and generating a strong fluorescence signal.

Colorimetric Biosensor for Multiplex Pathogen Detection

This protocol, from Wen et al., illustrates a nanoparticle-based approach for visually detecting multiple pathogens simultaneously [16].

- Core Principle: Different colored plasmonic nanoparticles (AuNPs: red, AgNPs: yellow) are conjugated to antibodies targeting specific pathogens. Magnetic separation is used to isolate pathogen-bound complexes, inducing a visible color change in the solution.

- Key Reagents:

- Plasmonic Nanoparticles: Gold nanoparticles (red), silver nanoparticles (yellow), silver triangular nanoplates (blue).

- Pathogen-Specific Antibodies: Immobilized on nanoparticles and magnetic beads.

- Magnetic Beads: For separation of target-bound complexes.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Form Sandwich Complex: Pathogens in the sample are bound by antibody-conjugated magnetic beads and antibody-conjugated nanoparticles of different colors.

- Magnetic Separation: A magnet pulls the sandwich complexes out of the solution.

- Colorimetric Readout: The supernatant's color changes depending on which pathogen-nanoparticle complexes were removed. The remaining color provides a visual indication of the pathogens present.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and implementation of advanced optical biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions in typical experimental setups.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biosensing | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Colorimetric probes due to LSPR; SERS substrates; scaffolds for biomolecule immobilization [17] [16] [22]. | Multiplex pathogen detection [16]; Metal ion sensing [22]. |

| DNAzymes | Catalytic DNA molecules that recognize specific metal ions or act as biocatalysts for signal amplification [21]. | Ultrasensitive detection of Pb²⁺ [21]; miRNA detection [18]. |

| Metal Nanoclusters (Au/Ag/Cu NCs) | Fluorescent probes with high photostability and biocompatibility; used as labels in optical assays [23]. | Fluorescent and colorimetric detection of viruses and bacteria [23]. |

| 11-Mercaptoundecanoic Acid (MUA) | Forms self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold surfaces, providing carboxyl groups for covalent antibody immobilization [20]. | SPR and electrochemical SPR biosensor construction [20]. |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Crosslinkers for activating carboxyl groups to form stable amide bonds with primary amines on antibodies or other biomolecules [20]. | Covalent immobilization of antibodies on sensor surfaces [20]. |

| Methylene Blue | Used as a Raman tag (for SERS) and an electrochemical redox probe, enabling dual-mode detection [18]. | SERS/EC dual-mode biosensors [18]. |

The choice of an optical detection method is a critical decision that hinges on the specific requirements of the assay. SPR is unparalleled for label-free kinetic studies, while fluorescence offers exceptional sensitivity for trace analysis. Colorimetric sensors are ideal for rapid, low-cost POC applications, and SERS provides unmatched molecular specificity. The emerging trend of combining optical with electrochemical methods creates powerful hybrid tools that leverage the strengths of both approaches, paving the way for more robust, sensitive, and versatile diagnostic platforms in biomedical research and drug development.

The evolution of biosensing technology is intrinsically linked to the development of novel nanomaterials that push the boundaries of detection sensitivity, selectivity, and miniaturization. As the critical comparative analysis between optical and electrochemical biosensors continues to shape research directions, the integration of advanced nanomaterials has become a pivotal strategy for enhancing biosensor performance. Within this context, metal nanoclusters, graphene, and MXenes have emerged as particularly promising materials, each offering a unique set of physicochemical properties that address specific limitations in biosensor design. This guide provides an objective comparison of how these nanomaterials enhance biosensor performance, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of materials for next-generation diagnostic platforms.

The fundamental distinction between optical and electrochemical biosensors lies in their transduction mechanisms. Optical biosensors detect analytes by measuring changes in light properties (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence, surface plasmon resonance) resulting from biochemical interactions [1]. In contrast, electrochemical biosensors convert biological recognition events into measurable electrical signals (e.g., current, voltage, impedance) [1]. Each platform presents characteristic advantages and limitations concerning sensitivity, multiplexing capability, portability, and cost, which are further modulated by the choice of nanomaterial.

Performance Comparison of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

The integration of nanomaterials into biosensing platforms significantly augments their performance metrics. The table below summarizes key quantitative data comparing the enhancement effects of metal nanoclusters, graphene, and MXenes on both optical and electrochemical biosensors.

Table 1: Performance comparison of biosensors enhanced by different nanomaterials

| Nanomaterial | Biosensor Type | Detection Limit | Key Advantages | Reported Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene | Electrochemical | Femtomolar (fM) range [24] | Large surface area (~2630 m²/g), high carrier mobility (>200,000 cm²/V·s), excellent biocompatibility [24] | Detection of dopamine, glucose, cancer biomarkers, viral infections [25] [24] |

| Graphene | Optical (SPR) | Not specified | Enhances electromagnetic field, improves SPR sensitivity [24] | Hemoglobin detection for anemia diagnosis [24] |

| MXenes | Electrochemical | Not specified | High electrical conductivity (>20,000 S cm⁻¹), hydrophilicity, facile functionalization, mechanical flexibility [26] [27] [28] | Detection of pollutants, heavy metals, biomarkers (e.g., glucose, H₂O₂) [29] [26] |

| MXenes | Optical | Not specified | Tunable optical properties, strong light-matter interaction [26] | Chemical and biological sensing [26] |

| Metal Nanoclusters | Optical | Not specified | Intense fluorescence, excellent photostability, tunable emission | Not specified in provided search results |

Table 2: Comparative analysis of nanmaterial properties relevant to biosensing

| Property | Graphene | MXenes | Metal Nanoclusters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | Very High (>200,000 cm²/V·s) [24] | Very High (>20,000 S cm⁻¹) [26] | Variable |

| Surface Area | Very High (~2630 m²/g) [24] | High [27] [28] | Moderate |

| Biocompatibility | Excellent [24] | Good [27] [28] | Good |

| Functionalization Ease | Moderate to High [24] | High [27] [28] | High |

| Optical Properties | Fluorescence quenching, SPR enhancement [24] | Tunable absorption, plasmonic [26] | Strong fluorescence |

| Mechanical Flexibility | High [24] | High [26] [27] | Low |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fabrication of Graphene-Based Electrochemical Biosensors

Protocol Title: Fabrication of Graphene Field-Effect Transistor (GFET) for Protein Detection

Principle: GFETs operate by detecting changes in electrical conductance when target biomolecules bind to receptors on the graphene surface, altering the local electric field [24].

Materials Required:

- Substrate: Silicon wafer with SiO₂ layer

- Graphene synthesis: Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) system

- Electrodes: Photolithography equipment and metal evaporator (Cr/Au)

- Biorecognition element: Specific antibodies or aptamers

- Functionalization reagents: 1-pyrenebutanoic acid succinimidyl ester (PBASE) as a linker molecule

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Graphene Transfer: Synthesize monolayer graphene via CVD on a copper foil. Transfer onto the SiO₂/Si substrate using a polymer-assisted wet transfer method [24].

- Electrode Patterning: Define source and drain electrode patterns via photolithography and deposit chromium (5 nm) and gold (50 nm) layers by thermal evaporation, followed by lift-off processing [24].

- Surface Functionalization: Incubate the GFET device with a solution of PBASE linker molecule. Wash thoroughly to remove unbound linkers [24].

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Covalently attach the chosen antibodies or aptamers to the PBASE-modified graphene surface via amine coupling chemistry. Block nonspecific binding sites with bovine serum albumin (BSA) [24].

- Electrical Characterization: Measure the source-drain current versus gate voltage (I-Vg) before and after exposure to the target analyte to establish the detection signal [24].

Development of MXene-Based Electrochemical Biosensors

Protocol Title: MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ)-Modified Screen-Printed Electrode for H₂O₂ Detection

Principle: MXenes enhance electron transfer kinetics at the electrode-electrolyte interface. The high conductivity and catalytic activity of Ti₃C₂Tₓ enable sensitive amperometric detection of electroactive species [29] [27].

Materials Required:

- MXene synthesis: MAX phase (Ti₃AlC₂) powder, hydrofluoric acid (HF) or other etching agents

- Electrode: Commercial screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs)

- Instrumentation: Electrochemical workstation (potentiostat)

- Analyte: Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) solutions of known concentrations

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- MXene Synthesis: Etch the aluminum layer from Ti₃AlC₂ powder using HF (e.g., 5-30 wt%) for 24-48 hours at room temperature. Centrifuge and wash the resulting multilayered Ti₃C₂Tₓ until the supernatant reaches neutral pH [27].

- Delamination: Intercalate dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) between the MXene layers. Subject the mixture to sonication in water to produce a colloidal suspension of single- or few-layer Ti₃C₂Tₓ nanosheets [27].

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast a precise volume (e.g., 5 µL) of the Ti₃C₂Tₓ dispersion onto the working electrode of SPCEs and allow to dry under ambient conditions [29].

- Electrochemical Detection: Perform amperometric measurements by applying a constant potential (e.g., +0.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl) to the MXene-modified SPCE while successively adding aliquots of H₂O₂ standard solution under stirred conditions. The measured current is proportional to the H₂O₂ concentration [29].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the general working principles of nanomaterial-enhanced optical and electrochemical biosensors, highlighting the role of the nanomaterials in the signal transduction process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development of nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for nanomaterial-based biosensor development

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| MAX Phase Precursors | Starting material for MXene synthesis | Ti₃AlC₂ powder for producing Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXenes [27] |

| Etching Agents | Selective etching of the 'A' layer from MAX phases | Hydrofluoric Acid (HF), Fluoride salts (e.g., LiF) in HCl [27] |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) System | Synthesis of high-quality, large-area graphene films | CVD with CH₄ gas source and Cu/Ni foil substrate [24] |

| Linker Molecules | Immobilization of biorecognition elements on nanomaterial surfaces | 1-pyrenebutanoic acid succinimidyl ester (PBASE) for graphene [24] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized platforms for electrochemical sensing | Carbon, gold, or platinum working electrodes [29] |

| Biorecognition Elements | Provide specificity for the target analyte | Antibodies, DNA aptamers, enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) [9] [24] |

| Electrochemical Workstation | Measures electrical signals in electrochemical biosensors | Potentiostat for amperometric, potentiometric, impedimetric measurements [1] |

The strategic integration of nanomaterials represents a cornerstone in the advancement of both optical and electrochemical biosensing platforms. Graphene excels in applications demanding ultra-high electrical conductivity and large surface area, making it particularly effective in field-effect transistors and electrochemical sensors. MXenes offer a compelling combination of metallic conductivity, hydrophilicity, and ease of functionalization, showing outstanding promise for flexible and wearable electrochemical sensors. While specific data for metal nanoclusters was limited in the provided sources, their strong fluorescence properties make them inherently valuable for optical sensing applications.

The choice between optical and electrochemical platforms, and the selection of the most appropriate nanomaterial, ultimately depends on the specific application requirements, including the desired sensitivity, portability, multiplexing capability, and cost constraints. Future research will likely focus on overcoming challenges related to the scalable synthesis and long-term stability of these nanomaterials, as well as their integration into multifunctional, point-of-care diagnostic devices that can revolutionize healthcare monitoring and disease management.

Electrochemical and optical biosensors have independently established themselves as powerful platforms for detection across clinical, environmental, and food safety domains. Electrochemical biosensors excel with their high sensitivity, portability, and capacity for miniaturized, low-cost point-of-care (POC) testing [9] [30]. Optical biosensors, including those based on fluorescence, chemiluminescence (CL), and surface plasmon resonance (SPR), offer advantages in real-time monitoring, visual readouts (in some formats), and high specificity [9] [31]. However, each modality faces inherent limitations: electrochemical methods can suffer from electrode fouling and interference in complex samples, while optical techniques may be limited by photobleaching, light scattering, and the need for sophisticated instrumentation [32] [15].

To overcome these constraints and meet the demand for more robust, reliable, and information-rich analytical systems, a new frontier has emerged: hybrid and dual-modality systems that integrate electrochemical and optical techniques. These systems synergistically combine the strengths of both approaches, enabling cross-validation of results, enhancing detection accuracy, expanding dynamic range, and providing complementary information from a single assay [32]. This convergence, often facilitated by advancements in nanomaterials and machine learning, represents a significant leap forward in biosensing capability, paving the way for next-generation diagnostics and monitoring platforms.

Comparative Analysis: Performance of Individual Modalities

Understanding the foundational characteristics of electrochemical and optical biosensors is crucial for appreciating their synergy in hybrid systems. The table below summarizes their core attributes, which directly inform their integration strategy.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of electrochemical and optical biosensors.

| Feature | Electrochemical Biosensors | Optical Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Very high (nanomolar to picomolar) [30] | High (e.g., single molecule detection possible with SERS) [9] [23] |

| Selectivity | High, dependent on bioreceptor (enzyme, antibody, aptamer) [6] [30] | High, dependent on bioreceptor and label specificity [9] |

| Portability | Excellent; compact electronics, low power requirements [9] [32] | Varies; colorimetric LFIA strips are highly portable, SPR/SERS systems less so [9] [31] |

| Cost | Generally low-cost and disposable [9] [30] | Varies; simple colorimetric strips are low-cost, while fluorescent/SPR systems are more expensive [15] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Good, with multi-electrode arrays [32] | Excellent, via multiple wavelengths or spatial encoding [31] |

| Key Advantages | Miniaturization, ease of integration with electronics, low sample volume [6] [32] | Visual readouts (in some cases), real-time monitoring, immunity to electromagnetic interference [9] [31] |

| Key Limitations | Susceptibility to electrode fouling, signal interference in complex matrices [32] | Potential for photobleaching, light scattering in turbid samples, may require complex optics [31] |

The Hybrid Paradigm: Mechanisms and Synergistic Benefits

Hybrid electrochemical-optical systems are not merely the physical co-location of two sensors. They are engineered platforms where the two modalities interact to create a combined output greater than the sum of their parts. The core mechanisms and benefits of this integration include:

Signal Amplification and Cross-Verification

Nanomaterials play a pivotal role in enhancing both signals. For instance, metal nanoclusters (MNCs) and nanoparticles can serve as electro-catalysts to amplify an electrochemical current while also acting as fluorescent or plasmonic labels for optical detection [23]. This dual functionality allows for internal validation, where the electrochemical signal confirms the optical readout and vice versa, drastically reducing false positives/negatives. A classic example is an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) system, where an electrochemical reaction generates an excited state species that then emits light, combining the controlled electrode reactivity of electrochemistry with the sensitive detection of optical methods [32].

Multi-Parameter and Multiplexed Detection

Hybrid systems can simultaneously monitor different aspects of a biological event. An electrochemical sensor can track a binding event via a change in impedance (e.g., using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, EIS), while a concurrent optical measurement like SPR or fluorescence can monitor a conformational change or the recruitment of a labeled secondary molecule [31]. This provides a more comprehensive picture of the analyte-bioreceptor interaction. Furthermore, this is powerful for multiplexing, where different optical labels (e.g., quantum dots with different emission wavelengths) can be used in conjunction with electrode-specific electrochemical signals to detect multiple targets in a single, small sample volume [32] [15].

Experimental Protocols for Hybrid Systems

Developing and characterizing a hybrid biosensor requires a methodical approach. The following is a generalized experimental workflow, adaptable for specific targets like pathogens, neurotransmitters, or cancer biomarkers.

Generalized Workflow for a Model Hybrid Biosensor

This protocol outlines the development of a biosensor using nanomaterials that exhibit both electrochemical and optical properties for the detection of a viral pathogen.

Table 2: Key stages in developing a hybrid biosensor.

| Stage | Description | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Probe Design & Synthesis | Functionalize gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) with a specific DNA aptamer for the target virus. The AuNC acts as both a fluorescent probe and an electroactive label. | Bioconjugated AuNCs with stable fluorescence and redox activity. |

| 2. Substrate Fabrication | Fabricate a microfluidic chip with an integrated 3-electrode system (WE, CE, RE). The working electrode is modified with a complementary DNA capture probe. | A ready-to-use sensor chip with immobilized capture probes. |

| 3. Assay Procedure & Detection | 1. Sample Incubation: Introduce the sample into the microfluidic chamber. If the target is present, it binds the AuNC-aptamer conjugate and the capture probe, forming a "sandwich" on the WE.2. Optical Measurement: Wash and measure the fluorescence intensity of the captured AuNCs.3. Electrochemical Measurement: In the same chamber, perform square-wave voltammetry (SWV) to measure the oxidation current of the AuNCs. | Two independent signals (fluorescence intensity and electrochemical current) proportional to the target concentration. |

| 4. Data Fusion & Analysis | Use a machine learning algorithm to correlate and analyze the dual signals, generating a calibrated and robust concentration readout. | A single, validated result with high confidence. |

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for a dual-modality aptasensor, showing the parallel optical and electrochemical detection paths culminating in data fusion.

Detailed Methodology: Electrochemical and Optical Interrogation

Following the assay formation, the detailed measurement steps are critical.

Optical Detection (Fluorescence):

- Excitation: Illuminate the sensor chamber with a light-emitting diode (LED) at the AuNC's excitation wavelength (e.g., 365 nm).

- Emission Capture: Collect the emitted fluorescence light through a miniaturized spectrometer or a filter-photodiode setup. A smartphone camera can also be used as a simple detector [9].

- Quantification: Measure the fluorescence intensity at the characteristic emission peak (e.g., 610 nm). Plot intensity against a calibration curve of known target concentrations.

Electrochemical Detection (Square-Wave Voltammetry - SWV):

- Buffer Condition: Ensure the chamber is filled with a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4).

- Parameter Setup: Apply a square-wave potential waveform to the working electrode versus the reference electrode. Typical parameters: potential window from 0.0 V to +0.8 V, step potential 4 mV, amplitude 25 mV, frequency 15 Hz.

- Current Measurement: Record the faradaic current generated from the oxidation of the AuNCs. The peak current is directly proportional to the number of AuNC labels captured, and hence, the target concentration.

- Data Processing: Integrate the oxidation peak and plot the charge or peak height against the calibration curve.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The performance of hybrid biosensors is critically dependent on the materials and reagents used. The table below catalogs key components and their functions in these advanced sensing systems.

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for hybrid biosensor development.

| Category / Reagent | Function in Hybrid Biosensors | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoclusters (AuNCs) | Fluorescent labels with well-defined redox electrochemistry; enable simultaneous optical and electrochemical signaling. | Signal probe in a sandwich assay for pathogen detection [23]. |

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes | Electrode modifiers that provide high conductivity, large surface area, and excellent electrocatalytic activity; enhance electrochemical signal and can quench fluorescence for "turn-on" assays. | Base material for working electrode to improve sensitivity for dopamine or cancer biomarkers [30]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Flexible, optically transparent polymer used for microfluidic chip and wearable sensor fabrication; allows for optical interrogation through the substrate. | substrate for a flexible wearable sensor that combines electrochemical sensing with optical readout via integrated LEDs [31]. |

| Specific Aptamers | Synthetic bioreceptors with high affinity for targets (ions, small molecules, proteins, cells); offer better stability and easier modification than antibodies. | Biorecognition element for the specific capture of a target like serotonin or a virus [6] [33]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Software tools for multivariate analysis and fusion of dual-signal data; compensate for sensor drift, minimize interference, and improve quantification. | Algorithm to deconvolute mixed electrochemical signals or correlate optical and electrical data for a more accurate diagnosis [32]. |

Signaling Pathways and System Logic

The core logic of a hybrid biosensor can be visualized as a process where a single biological event triggers two parallel, measurable physical changes. This is fundamental to understanding their design and advantage.

Figure 2: The core signaling logic of a hybrid biosensor, where a single biorecognition event, transduced by a nanomaterial, generates two parallel signals for fusion and validation.

Translating Technology to Practice: Applications in Disease Management and Diagnostics

Precision diagnostics for critical illnesses like cancer and autoimmune diseases rely on the sensitive and specific detection of biomarkers such as proteins, autoantibodies, and nucleic acids. Among the most promising technologies advancing this field are electrochemical and optical biosensors, which function as analytical devices by combining a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer [34] [9]. These systems convert specific biological interactions into quantifiable signals, enabling the detection and measurement of target analytes. Electrochemical biosensors detect electrical changes resulting from biorecognition events, while optical biosensors measure alterations in light properties [13] [9]. The evolution of these biosensing platforms is particularly crucial for diagnosing complex diseases, where early and accurate detection of biomarkers like carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) for cancers or specific autoantibodies for autoimmune conditions can dramatically influence treatment strategies and patient outcomes [34] [35]. The global biosensors market, projected to grow from US$30.6 billion in 2024 to US$49.6 billion by 2030, underscores their increasing clinical importance, with electrochemical biosensors currently dominating over 70% of the market share [36].

This comparative analysis examines the fundamental principles, performance characteristics, and practical applications of electrochemical and optical biosensors for detecting cancer biomarkers and clinically relevant antibodies. By evaluating recent experimental data and technological advancements, this guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a critical framework for selecting appropriate biosensing platforms based on their specific diagnostic requirements, whether for point-of-care testing, continuous monitoring, or high-throughput laboratory analysis.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Mechanisms

Electrochemical Biosensing Platforms

Electrochemical biosensors operate on the principle of detecting electrical changes—current, potential, or impedance—resulting from specific biological recognition events occurring at the electrode surface [6] [9]. These platforms typically employ a three-electrode system (working, reference, and counter electrodes) integrated within an electrochemical cell. When target biomarkers interact with biological recognition elements (such as antibodies, aptamers, or enzymes) immobilized on the electrode surface, subsequent electrochemical reactions generate measurable signals [6]. The key detection methodologies in electrochemical biosensing include amperometric techniques, which measure current from redox reactions at a constant potential; voltammetric methods like differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) and cyclic voltammetry (CV), which apply potential sweeps and measure resulting currents; and impedimetric approaches, which monitor changes in electrical impedance due to binding events [37] [9].

A significant advancement in this field involves nanoengineering electrode surfaces to enhance sensitivity and specificity. For instance, researchers have developed highly sensitive immunosensors by modifying glassy carbon electrodes with composite nanomaterials including sodium alginate (SA), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), and gamma-manganese dioxide/chitosan (γ.MnO₂-CS) [37]. This multi-layer architecture creates a high-surface-area scaffold that improves both biomolecule immobilization and electron transfer kinetics, significantly boosting detection capabilities for low-abundance biomarkers.

Optical Biosensing Platforms

Optical biosensors function by transducing biorecognition events into measurable optical signals through various mechanisms including absorption, fluorescence, chemiluminescence, or refractive index changes [9] [38]. These platforms leverage the interaction between light and biological recognition elements to detect and quantify target analytes. Common optical biosensing approaches include surface plasmon resonance (SPR), which detects refractive index changes near a metal surface; fluorescence-based sensors, which measure light emission from excited fluorophores; colorimetric sensors, which visualize color changes detectable by eye or simple spectrometers; and optical cavity-based sensors, which monitor resonance shifts in confined light structures [39] [38].

Advanced optical systems like optical cavity-based biosensors (OCB) utilize Fabry-Perot interferometer principles, where an optical cavity structure is created between two partially reflective surfaces [38]. When biomolecular binding occurs within this cavity, it alters the local refractive index and consequently modifies the resonance transmission spectrum. By employing differential detection methods using multiple laser wavelengths and monitoring intensity changes with CCD or CMOS sensors, these systems can achieve highly sensitive, label-free detection of target analytes without requiring complex optical instrumentation [38].

Comparative Operational Principles

The table below summarizes the core operational principles and signal transduction mechanisms for both biosensor types:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Biosensing Mechanisms

| Feature | Electrochemical Biosensors | Optical Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Transduction Principle | Detection of electrical changes from bio-recognition events | Measurement of optical property modifications |

| Key Measurement Parameters | Current, potential, impedance | Refractive index, fluorescence, absorbance, light intensity |

| Common Techniques | Amperometry, voltammetry (DPV, CV), impedimetry | SPR, fluorescence, colorimetric, optical cavity resonance |

| Signal Output | Electrical current/potential | Light intensity/wavelength shift |

| Label Requirement | Often label-free; sometimes uses enzymatic labels | Mix of label-free (SPR, OCB) and labeled approaches (fluorescence) |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Detection Capabilities

Sensitivity and Detection Limits for Cancer Biomarkers

Both electrochemical and optical biosensors have demonstrated exceptional sensitivity in detecting clinically relevant cancer biomarkers at concentrations crucial for early diagnosis. Recent experimental studies highlight their advancing capabilities:

Table 2: Comparison of Biosensor Performance in Cancer Biomarker Detection

| Biomarker | Biosensor Type | Detection Mechanism | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) | Electrochemical | Label-free immunosensor with γ.MnO₂-CS/AuNPs/SA modified GCE | 10 fg/mL - 0.1 µg/mL | 9.57 fg/mL | [37] |

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) | Optical (OCB) | Label-free cavity resonance shift | - | 377 pM | [38] |

| Streptavidin (Model System) | Optical (OCB) | Optimized APTES functionalization with cavity resonance | - | 27 ng/mL (3x improvement with methanol-based protocol) | [38] |

| Let-7a (Lung Cancer) | Electrochemical | DSN-based electrochemical biosensor | - | Not specified | [34] |

| ORAOV1 (Urothelial Carcinoma) | Electrochemical | TE-RPA electrochemical biosensor | - | Not specified | [34] |

Electrochemical biosensors have shown remarkable performance in detecting protein biomarkers like CEA, achieving detection limits as low as 9.57 fg/mL through sophisticated electrode modifications [37]. These platforms benefit from advanced nanocomposite materials that enhance electrode surface area and electron transfer efficiency. Similarly, optical biosensors like the OCB system have demonstrated continuous improvement in detection capabilities, with researchers achieving a threefold enhancement in streptavidin detection (LOD: 27 ng/mL) through optimized surface functionalization protocols using methanol-based APTES deposition [38].

Real-World Applicability and Analytical Performance

Beyond pure detection limits, several additional factors determine the practical utility of biosensing platforms in clinical settings:

Table 3: Analytical Performance and Practical Considerations

| Performance Parameter | Electrochemical Biosensors | Optical Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate | High (especially imaging-based platforms) |

| Sample Volume Requirements | Low (microliters) | Variable (microliters to milliliters) |

| Measurement Time | Seconds to minutes | Minutes (including equilibrium time) |

| Portability | High (miniaturizable, low-power) | Moderate (some require complex optics) |

| Integration with POC Devices | Excellent | Good (lateral flow, smartphone-based) |

| Susceptibility to Environmental Interference | Low to moderate | Moderate to high (sensitive to ambient light, temperature) |

Electrochemical platforms demonstrate particular strength in point-of-care settings due to their miniaturization potential, low power requirements, and compatibility with portable electronics [34] [36]. Optical biosensors excel in multiplexing applications and offer superior sensitivity in laboratory environments, with ongoing research focused on enhancing their field-deployability through smartphone integration and simplified optical components [39] [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Electrochemical Immunosensor for CEA Detection

The development of a highly sensitive CEA immunosensor exemplifies the sophisticated methodology employed in electrochemical biosensing [37]:

Electrode Modification Protocol:

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) Preparation: Polish the GCE with alumina slurry, followed by sequential sonication in ethanol and deionized water, then dry at room temperature.

- Sodium Alginate (SA) Modification: Deposit 6 μL of SA solution (2.5 mM prepared in phosphate buffer) onto the GCE surface and allow it to dry.

- Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) Immobilization: Drop-cast 6 μL of citrate-modified AuNPs (250 μM) onto the SA-modified GCE and dry.

- Nanocomposite Integration: Apply 6 μL of the γ.MnO₂-CS nanocomposite suspension onto the AuNPs/SA/GCE assembly and dry.

- Antibody Immobilization: Introduce 6 μL of anti-CEA antibody (12 μg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) to the modified electrode and incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Blocking Step: Treat the electrode with 6 μL of bovine serum albumin (BSA, 1% w/v) for 1 hour at room temperature to block non-specific binding sites.

Measurement Conditions:

- Employ differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements in a solution containing 2.5 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] (1:1 mixture) with 0.1 M KCl as supporting electrolyte.

- Apply a potential range from -0.2 to 0.6 V with a modulation amplitude of 0.025 V and a step potential of 0.005 V.

- Quantify CEA concentrations by monitoring current variations at the oxidation peak resulting from antibody-antigen complex formation.

Protocol 2: Optical Cavity-Based Biosensor with Optimized APTES Functionalization

The enhanced performance of optical biosensors relies critically on controlled surface chemistry, as demonstrated in this streptavidin detection protocol [38]:

Surface Functionalization Optimization:

- Substrate Cleaning: Treat soda lime glass substrates with oxygen plasma for 5 minutes to create hydrophilic surfaces.

- APTES Functionalization (Methanol-Based Optimal Protocol):

- Prepare a fresh solution of 0.095% (v/v) APTES in anhydrous methanol.

- Immerse the cleaned substrates in the APTES solution for 30 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Rinse thoroughly with methanol to remove physically adsorbed silane.

- Cure the functionalized substrates at 110°C for 10 minutes to stabilize the silane layer.

- Biotin Receptor Immobilization:

- Incubate the APTES-functionalized surface with sulfo-NHS-biotin (0.5 mg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Wash with phosphate buffer to remove unbound biotin.

- Biomolecule Attachment: Introduce streptavidin samples in PBS buffer and monitor binding in real-time.

Optical Measurement Setup:

- Utilize a differential detection approach employing two laser diodes at 808 nm and 880 nm.

- Direct collimated light through the optical cavity structure and measure transmission intensity with a CCD or CMOS camera.

- Monitor intensity changes resulting from streptavidin-biotin binding-induced refractive index modifications within the optical cavity.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Electrochemical Biosensor Signaling Pathway

Electrochemical Biosensor Signaling Pathway

Optical Biosensor Experimental Workflow

Optical Biosensor Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of biosensing platforms requires carefully selected materials and reagents optimized for specific detection methodologies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensing | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Glassy carbon electrode (GCE), Gold, Platinum | Provides conductive surface for electron transfer | GCE offers excellent electrochemical properties and modification versatility [37] |

| Nanomaterials | Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), Manganese dioxide (γ.MnO₂), Carbon nanotubes | Enhances surface area, electron transfer, and bioreceptor immobilization | AuNPs improve conductivity and biomolecule attachment [37] |

| Polymers & Biopolymers | Chitosan (CS), Sodium alginate (SA) | Creates 3D scaffolds for biomolecule encapsulation and stabilization | SA provides stable matrix for retaining nanocomposite structure [37] |

| Surface Functionalization | (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Forms amine-terminated linker layers for subsequent biomolecule attachment | Methanol-based protocol (0.095% APTES) optimal for uniform layers [38] |

| Recognition Elements | Anti-CEA antibodies, Streptavidin-Biotin pair | Provides specific molecular recognition for target analytes | Antibodies selected for high specificity and affinity [37] |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | Reduces non-specific binding on sensor surfaces | 1% BSA solution typically used for effective blocking [37] |

| Electrochemical Mediators | K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] | Facilitates electron transfer in redox reactions | 2.5 mM concentration in supporting electrolyte [37] |

| Optical Components | Laser diodes (808 nm, 880 nm), CCD/CMOS detectors | Enables precise optical signal generation and detection | Differential detection with multiple wavelengths enhances sensitivity [38] |

Electrochemical and optical biosensors represent complementary technologies advancing precision diagnostics for critical illnesses. Electrochemical platforms offer superior portability, minimal sample requirements, and cost-effectiveness—attributes ideal for point-of-care testing and resource-limited settings [34] [36]. Their dominance in the current market (over 70% share) reflects these practical advantages, particularly for applications like glucose monitoring and rapid cancer biomarker screening [36]. Optical biosensors provide exceptional sensitivity, robust multiplexing capabilities, and strengths in laboratory environments where complex sample analysis is required [39] [38].

The evolving integration of both technologies with artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and IoT connectivity promises to further enhance their diagnostic capabilities [39] [36]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selection between these platforms should be guided by specific application requirements: electrochemical biosensors for decentralized testing and rapid results, optical biosensors for maximum sensitivity and multi-analyte detection in controlled settings. As both technologies continue to mature through ongoing research in materials science, surface chemistry, and device integration, they will undoubtedly play increasingly pivotal roles in the future landscape of precision medicine for cancer and critical illness management.

The rapid and accurate detection of pathogenic bacteria and viruses is fundamental to safeguarding public health, enabling timely interventions, and preventing the spread of infectious diseases [40]. Conventional detection methods, such as culture techniques, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), are often hindered by lengthy processing times, high costs, and the need for specialized equipment and personnel [40] [41] [16]. In recent years, biosensors incorporating metal nanoclusters (MNCs) have emerged as powerful diagnostic platforms that address these limitations [40].

Metal nanoclusters, composed of a few to hundreds of atoms (typically <3 nm), occupy a unique space between single atoms and larger nanoparticles [42]. Their ultra-small size confers molecule-like properties, including discrete electronic energy levels, strong photoluminescence, and size-dependent catalytic activity, making them superior to traditional nanoparticles for many sensing applications [40] [42]. This review performs a comparative analysis of optical and electrochemical biosensors utilizing MNCs for pathogen detection. It objectively evaluates their performance based on sensitivity, specificity, and operational characteristics, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear guide to the current state of this rapidly advancing technology.

Metal Nanoclusters: Synthesis and Functional Properties

Synthesis and Tunability

The synthesis of metal nanoclusters has evolved significantly beyond classical wet-chemical reduction methods. Emerging strategies such as microwave-assisted, photochemical, and sonochemical synthesis have improved efficiency, structural control, and environmental compatibility [42]. For instance, microwave-assisted synthesis of histidine-stabilized gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) not only reduced reaction time to 30 minutes but also yielded clusters with a fourfold higher photoluminescence intensity compared to those synthesized via classical room-temperature protocols [42]. These advances enable the precise tuning of MNC properties by controlling their size, composition (e.g., Au, Ag, Cu), and surface chemistry through the selection of protecting ligands like peptides, proteins, and nucleic acids [43] [42]. This tunability is critical for designing biosensors with optimized performance for specific pathogenic targets.

Key Functional Properties for Biosensing

The exceptional properties of MNCs make them ideal transducers and signal amplifiers in biosensors:

- Strong Photoluminescence: MNCs exhibit strong and tunable fluorescence, which arises from their discrete electronic states and ligand-metal interactions [40] [42]. Mechanisms such as ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) and aggregation-induced emission (AIE) can be harnessed for highly sensitive optical detection [42].

- Electrocatalytic Activity: Atomically precise MNCs possess high specific surface areas and unique electronic structures, enabling them to promote electron exchange and act as redox mediators in electrochemical sensing platforms, significantly enhancing signal response [43].

- Biocompatibility and Stability: The use of biocompatible ligands (e.g., glutathione, proteins) for stabilization facilitates the functionalization of MNCs with biological recognition elements and ensures performance in complex biological matrices [40] [42].

Comparative Analysis: Optical vs. Electrochemical MNC-Based Biosensors

The integration of MNCs into biosensing platforms has led to significant advancements, primarily in optical and electrochemical modalities. The table below provides a comparative overview of their operating principles, advantages, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Optical and Electrochemical MNC-Based Biosensors

| Feature | Optical Biosensors | Electrochemical Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Transduction Mechanism | Measures changes in light properties (e.g., intensity, wavelength) [16] | Measures changes in electrical properties (e.g., current, impedance) [43] [44] |

| Key Sub-types | Fluorescence, Colorimetric, Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) [40] [16] | Voltammetry (DPV, SWV), Amperometry, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [43] [44] |

| Typical Limit of Detection (LOD) | Very high (e.g., 10 CFU/mL for colorimetric [16]; can detect single molecules) | Very high (e.g., attomolar-femtomolar for biomarkers [43]) |

| Advantages | High sensitivity and specificity; potential for multiplexing and visual readouts; portability [45] [16] | High sensitivity; rapid detection; low fabrication cost; ease of miniaturization and analysis [43] [44] |

| Limitations/Challenges | Susceptible to light quenching and autofluorescence in complex samples [44] | Can have weaker stability and be susceptible to fouling in complex matrices [44] |

| Example Pathogen Detected | Salmonella, S. aureus, E. coli O157:H7, SARS-CoV-2 [40] [16] | Disease biomarkers (proteins, nucleic acids) for viral and bacterial infections [43] |

Performance Data and Experimental Protocols

The following tables summarize experimental data from representative studies to quantitatively compare the performance of optical and electrochemical MNC-based biosensors in detecting pathogens.

Table 2: Performance of Selected Optical MNC-Based Biosensors for Pathogen Detection

| Target Pathogen | MNC Type & Recognition Element | Detection Mechanism | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Assay Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2, S. aureus, Salmonella | AuNPs, AgNPs / Specific antibodies | Colorimetric (sandwich immunoassay with magnetic separation) | Not specified | Not specified | [16] |

| S. aureus, E. coli | Nanoarray / Not specified | Colorimetric (optical image analysis after capture) | 10 CFU/mL | < 10 min | [16] |

| Eight bacterial species | 3-hydroxyflavone derivatives | Ratiometric fluorescence | Not specified | Not specified | [16] |

Table 3: Performance of Selected Electrochemical MNC-Based Biosensors for Disease Biomarkers

| Target Analyte (Model) | MNC Type & Electrode Modification | Detection Technique | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|