Monte Carlo Simulation for Light Propagation in Tissue: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Monte Carlo (MC) simulation for modeling light propagation in biological tissue, a gold-standard technique in biomedical optics.

Monte Carlo Simulation for Light Propagation in Tissue: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Monte Carlo (MC) simulation for modeling light propagation in biological tissue, a gold-standard technique in biomedical optics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational physics of light-tissue interactions and the core principles of the MC method. The scope extends to practical implementation using established software tools, advanced applications in photoacoustic imaging and optogenetics, and strategies for optimizing computational efficiency and model accuracy. A strong emphasis is placed on validation protocols, comparing MC results with experimental data and alternative models, and discussing its critical role in virtual clinical trials for accelerating the development of optical imaging and therapeutic technologies.

The Physics of Light in Tissue and Core Principles of the Monte Carlo Method

The study of light-tissue interactions forms the foundational basis for a wide array of non-operative diagnostic methods and therapeutic applications in modern medicine. Optical techniques including diffuse reflection spectroscopy (DRS), near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), diffuse optical tomography (DOT), Raman imaging, fluorescence imaging, optical microscopy, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and photoacoustic (PA) imaging have emerged as powerful tools in biomedicine, offering the significant advantage of utilizing non-ionizing radiation while maintaining non-invasiveness [1]. The potential of these modalities remains far from fully explored, driving continued research into the fundamental principles governing light propagation through biological media.

At the heart of understanding these optical techniques lies the complex interplay between light and the intricate structural components of biological tissue. When photons encounter tissue, they undergo a series of interactions including absorption, scattering, and potential fluorescence re-emission that collectively determine the spatial and temporal distribution of light within the medium. Modeling these interactions accurately is essential for advancing both diagnostic imaging capabilities and light-based therapies such as photodynamic therapy (PDT) [2].

The Monte Carlo (MC) simulation approach has established itself as the gold standard for modeling light propagation in scattering and absorbing media like biological tissue [1] [3]. This computational method provides a flexible framework for simulating the random walk of photons as they travel through tissue, undergoing absorption and scattering events based on the statistical probabilities derived from the optical properties of the medium. For researchers investigating light-tissue interactions, MC methods offer unparalleled accuracy in predicting light distribution in complex, heterogeneous tissue geometries that defy analytical solutions.

Fundamental Optical Properties of Tissue

The propagation of light in biological tissues is governed by three fundamental optical properties that determine how photons interact with the medium: the absorption coefficient, the scattering coefficient, and the anisotropy factor. These parameters collectively define the behavior of light as it travels through tissue and forms the basis for all computational models of light transport.

Absorption Coefficient (μa)

The absorption coefficient (μa) represents the probability of photon absorption per unit infinitesimal path length in a medium [1]. This parameter is intrinsically linked to the molecular composition of the tissue, as different chromophores—including hemoglobin, melanin, water, and lipids—exhibit distinct absorption spectra across the electromagnetic spectrum. In biological tissues, absorption coefficients can vary significantly depending on the wavelength and tissue type. In the red and near-infrared regions (λ > 625 nm), μa typically ranges between 0.01 and 0.5 cm⁻¹, while at shorter wavelengths (λ < 625 nm), absorption increases substantially, with values ranging from 0.5 to 5 cm⁻¹ due primarily to hemoglobin absorption [4]. The strong absorption of hemoglobin at visible wavelengths has important implications for fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) and bioluminescence tomography (BLT) of fluorescent proteins and luciferase, whose emission peaks fall within these highly absorptive regions [4].

Scattering Coefficient (μs) and Reduced Scattering Coefficient (μ's)

The scattering coefficient (μs) quantifies the probability of a photon scattering event per unit path length and primarily depends on the density and size distribution of microscopic spatial variations in refractive index within the tissue [1]. These variations arise from subcellular structures, cell membranes, and extracellular matrix components. In biological tissues, μs typically ranges between 10 and 200 cm⁻¹ across visible and near-infrared wavelengths [4]. A more clinically relevant parameter is the reduced scattering coefficient (μ's), defined as μ's = (1 - g)μs, where g is the anisotropy factor [4]. This parameter accounts for the net effect of scattering after considering the directional preference of scattering events. Typical reduced scattering coefficients in tissues range between 4 and 15 cm⁻¹ and exhibit slight wavelength dependence [4].

Anisotropy Factor (g)

The anisotropy factor (g) represents the mean cosine of the scattering angle and quantifies the directional preference of scattering events within tissue [1]. This parameter ranges from -1 (perfect backscattering) to +1 (perfect forward scattering), with g = 0 representing isotropic scattering. In biological tissues, light scattering is strongly forward-peaked, with g typically varying between 0.5 and 0.95 depending on the specific tissue type [4]. This strong forward scattering behavior significantly influences light penetration depth and the overall distribution of light within tissue.

Table 1: Representative Ranges of Optical Properties in Biological Tissues

| Optical Property | Symbol | Typical Range | Wavelength Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient | μa | 0.01-5 cm⁻¹ | Strong; varies with chromophore concentration |

| Scattering Coefficient | μs | 10-200 cm⁻¹ | Moderate; generally decreases with increasing wavelength |

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient | μ's | 4-15 cm⁻¹ | Moderate; generally decreases with increasing wavelength |

| Anisotropy Factor | g | 0.5-0.95 | Weak; may vary with tissue microstructure |

The relationship between these optical properties defines two important metrics for light transport: the mean free path (mfp), which is the average distance between interaction events (1/(μs + μa)), and the transport mean free path (tmfp), which represents the distance over which photon direction becomes randomized (1/(μ's + μa)) [4]. These parameters play a crucial role in determining the appropriate modeling approach for light propagation in different tissue types and geometries.

Monte Carlo Simulation of Light Transport

Monte Carlo (MC) simulation represents the most accurate and flexible approach for modeling light propagation in biological tissues, particularly in cases involving complex geometries, heterogeneous optical properties, or non-diffusive regimes where simplified models fail. The MC method treats light as a series of photon packets that undergo stochastic interactions—including absorption, scattering, and boundary effects—as they travel through the tissue medium [1] [2]. By simulating a sufficiently large number of photon trajectories, MC methods can provide highly accurate solutions to the radiative transfer equation (RTE) that governs light transport in scattering media.

Fundamental Principles of MC Simulation

In MC simulations, a large number of photons (conceptually represented as photon packets with statistical weight) are propagated through the tissue medium under study [1]. Each photon packet begins with an initial statistical weight (W₀) and undergoes a random walk process through the tissue, with interactions governed by the optical properties of the medium: refractive index (n), absorption coefficient (μa), scattering coefficient (μs), and scattering anisotropy (g) [1]. The simulation tracks each photon through a sequence of elementary steps: generation of the photon path length, scattering, and refraction/reflection at boundaries.

The core of the MC approach lies in its statistical treatment of photon transport. The path length between interactions is sampled from an exponential distribution based on the total attenuation coefficient (μt = μa + μs). At each interaction point, the photon packet may be absorbed or scattered, with the probability of absorption given by μa/μt. To conserve energy while maintaining computational efficiency, the "Russian roulette" method is often employed when the statistical weight of a photon packet becomes small, giving the photon a chance to continue with increased weight (n·W, where n is between 10-20) or be terminated [1]. While this approach saves computational resources, it can introduce uncertainty in the distribution of photon paths and presents challenges in physical interpretation.

Scattering Phase Functions

The direction of photon scattering at each interaction point is determined by a scattering phase function, which describes the angular distribution of scattered light. The most commonly used phase function in tissue optics is the Henyey-Greenstein (HG) phase function, expressed as:

[ p(\cos\theta) = \frac{1 - g^2}{2(1 + g^2 - 2g\cos\theta)^{3/2}} ]

where θ is the polar scattering angle and g is the anisotropy factor [1]. The azimuthal angle φ is typically assumed to be uniformly distributed between 0 and 2π, calculated as φ = 2πξ, where ξ is a uniformly distributed random number between 0 and 1 [1].

While the Henyey-Greenstein function is widely used due to its mathematical simplicity and ability to represent the strongly forward-peaked scattering typical of biological tissues, it is not the only option. Several authors have introduced Markov chain solutions to model photon multiple scattering through turbid media via more complex anisotropic scattering processes, such as Mie scattering [1]. These approaches can effectively handle non-uniform phase functions and absorbing media by converting the complex multiple scattering problem into a matrix form, computing transmitted/reflected photon angular distributions through relatively simple matrix multiplications [1].

Advanced MC Implementation Considerations

Modern MC implementations for light transport in tissues have evolved to address various computational and practical challenges. The use of graphics processing units (GPUs) has enabled near real-time simulation of complex, three-dimensional samples based on clinical CT images, facilitating applications in treatment planning for procedures such as interstitial photodynamic therapy [2]. These advanced MC models can incorporate various fiber geometries, including physically accurate representations of cylindrical diffusing fibers used in clinical applications [2].

For specialized tissues with aligned cylindrical microstructures (e.g., muscle, skin, bone, tooth), MC simulations can employ more specific phase functions, such as those for infinitely long cylinders, to accurately capture the pronounced anisotropic light scattering effects that produce directionally dependent reflectance patterns [5]. These implementations demonstrate how MC methods can be adapted to address the unique optical characteristics of different tissue types.

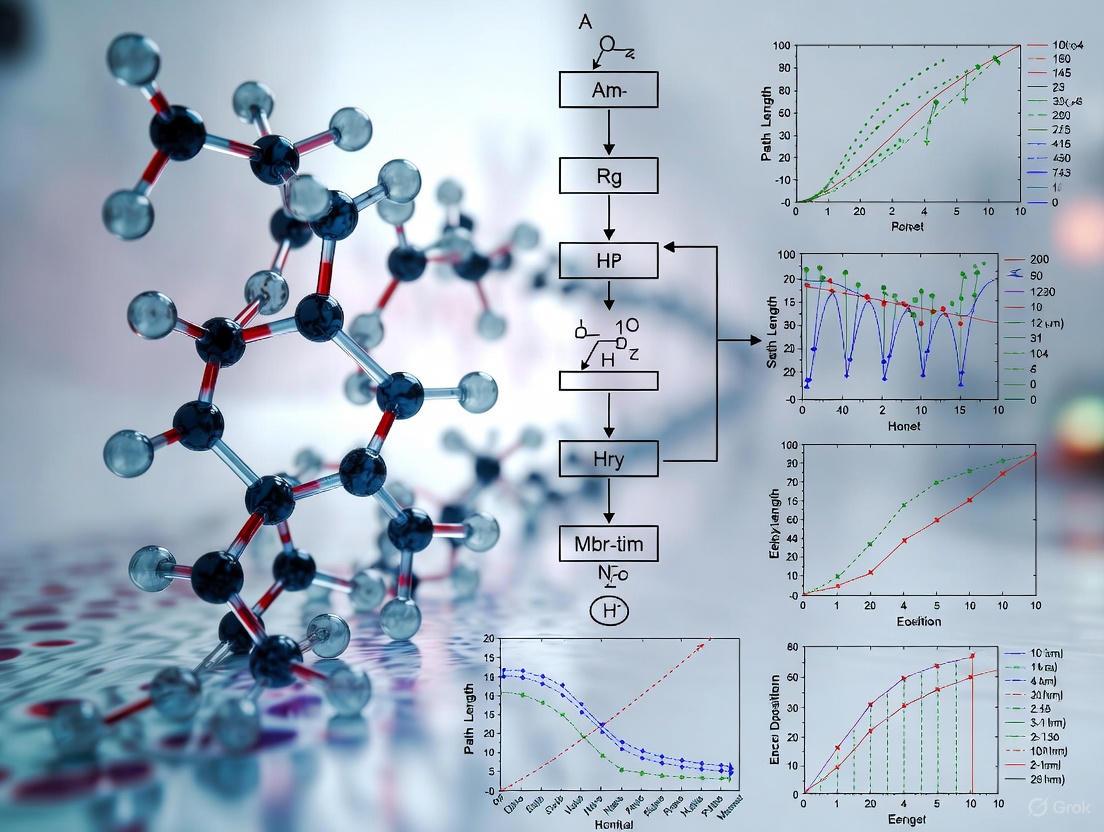

Diagram 1: Monte Carlo photon propagation workflow showing key decision points and processes.

Experimental Determination of Optical Properties

Accurate determination of optical properties is a prerequisite for meaningful MC simulations of light-tissue interactions. Several experimental approaches have been developed to measure these parameters, with the integrating sphere system coupled with inverse solving algorithms representing one of the most widely used methodologies.

Integrating Sphere Measurements and IAD Algorithm

The single-integrating sphere (SIS) system combined with the inverse adding-doubling (IAD) algorithm provides a robust approach for determining the optical properties of biological tissues across the visible and near-infrared spectrum [3]. This methodology involves measuring both total diffuse reflectance (Rt) and total transmittance (Tt) from tissue samples of known thickness, then applying the IAD algorithm to extract the absorption and scattering parameters.

A typical SIS setup consists of an integrating sphere (e.g., 36 mm diameter with a 9 mm sample port) with an inner surface coated with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which provides high, uniform reflectivity (approximately 0.90) [3]. The system includes a broadband light source such as a 150 W adjustable power halogen lamp and a Vis-NIR spectrometer covering wavelengths from 400 to 1000 nm [3]. All measurements should be conducted within a light-proof enclosure to eliminate interference from ambient light.

For biological tissues like potato tubers used in model studies, samples are typically sectioned into approximately 2 mm thick slices from the inner medulla tissues [3]. Each slice is measured in both reflection and transmission modes by adjusting the sphere configuration. The resulting Rt and Tt values serve as inputs to the IAD algorithm, which computationally solves the inverse problem to determine the optical properties that would produce the measured reflectance and transmittance values.

Table 2: Key Components of Single-Integrating Sphere System for Optical Property Determination

| Component | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Integrating Sphere | 36 mm diameter, PTFE coating (R ≈ 0.90) | Collects and uniformly distributes reflected or transmitted light |

| Light Source | 150 W halogen lamp, 400-1000 nm | Provides broadband illumination for spectral measurements |

| Spectrometer | USB2000+, 400-1000 nm range | Measures intensity of reflected/transmitted light at different wavelengths |

| Sample Port | 9 mm diameter | Standardized opening for consistent sample measurement |

| Enclosure | Light-proof | Eliminates ambient light interference during measurements |

Complementary Physicochemical Characterization

To correlate optical properties with underlying tissue structure and composition, complementary physicochemical characterization is often performed on the same sampling regions used for optical measurements. These analyses may include:

Color measurement using a digital colorimeter expressed in the CIE Lab* color space, where L* represents lightness, a* indicates green-red tendency, and b* represents blue-yellow tendency [3]. The overall color difference (ΔE) is calculated as the Euclidean distance in this color space.

Dry matter (DM) content determination by drying tissue samples at 105°C until constant mass is achieved [3].

Microstructural analysis using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), where samples are sectioned into slices (e.g., 10 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm), dehydrated, freeze-dried, and sputter-coated with gold prior to imaging [3].

These complementary measurements help establish relationships between tissue microstructure, biochemical composition, and optical properties, providing deeper insight into the fundamental factors governing light-tissue interactions.

Beyond MC: Alternative Modeling Approaches

While MC simulation offers high accuracy and flexibility for modeling light transport in tissues, its computational intensity has motivated the development of alternative approaches that provide different trade-offs between accuracy, speed, and implementation complexity.

Simplified Spherical Harmonics (SPN) Equations

The simplified spherical harmonics (SPN) equations represent a higher-order approximation to the radiative transfer equation that significantly improves upon the diffusion approximation while being less computationally expensive than full spherical harmonics (PN) or discrete ordinates (SN) methods [4] [6]. The SPN method approximates the RTE by a set of coupled diffusion-like equations with Laplacian operators, avoiding the complexities of the full PN approximation which involves mixed spatial derivatives [4].

The SPN equations are particularly valuable for modeling light propagation in regimes where the diffusion approximation fails, including situations involving strong absorption (μₐ ≪ μ'ₛ is not satisfied), small tissue geometries, and regions near sources or boundaries [4] [6]. For example, in small animal imaging or when using visible light in fluorescence molecular tomography, absorption coefficients can be sufficiently high (0.7-2.7 cm⁻¹ for highly vascularized tissues) to invalidate the diffusion approximation [4]. In such cases, the error of fluence calculated near sources between the diffusion approximation and SPN models can be as large as 60% [6].

The SPN method offers several advantages: it captures most transport corrections to the diffusion approximation, requires solving fewer equations than full PN or SN methods, can be implemented using standard diffusion solvers, and avoids the ray effects that plague SN methods [4]. A disadvantage is that SPN solutions do not converge to exact transport solutions as N → ∞; rather, for each problem there is an optimal N that yields the best solution [4].

Beam Spread Function (BSF) Approach

For specific applications such as optogenetics, where estimating light transmission through brain tissue is crucial for controlling neuronal activation, the beam spread function (BSF) approach provides an analytical alternative to MC simulations [1]. The BSF method approximates light distribution in strongly scattering media by accounting for higher-order photons propagating via multiple paths of different lengths, and can also calculate time dispersion of light intensity [1].

In optogenetics applications, the BSF approach has demonstrated good agreement with both numerical MC simulations and experimental measurements in mouse brain cortical slices, yielding a cortical scattering length estimate of approximately 47 μm at λ = 473 nm [1]. This approach offers significantly faster simulation times than MC methods while maintaining comparable accuracy for specific problem geometries.

Reduced Models for Multiple Scattering

Beyond the comprehensive approaches of MC and SPN methods, several reduced models have been developed specifically for multiple scattering processes. These include the Random Walk theorem, empirical predictions, and adding-doubling methods [1]. These approaches typically employ simplified analytical expressions to predict behaviors such as the distribution of total transmission, average scattering cosine, and traveled distance.

While these reduced models provide reasonable results for some averaged observations, they have limitations in distinguishing between similar phase functions with identical anisotropy factors but different probability density functions, and in handling anisotropic scattering, absorbing media, and non-uniform distributions of optical density [1]. Nevertheless, they offer valuable computational efficiency for specific applications where their simplifying assumptions remain valid.

Applications and Case Studies

The principles of light-tissue interactions and MC simulation find application across diverse domains, from biomedical optics to agricultural product inspection. Examining specific case studies illustrates how these fundamental concepts are implemented in practical scenarios.

Case Study 1: Blackheart Detection in Potatoes

In agricultural applications, MC simulations have been employed to investigate light propagation in healthy versus blackhearted potato tissues, revealing significant differences in optical properties that enable non-destructive detection of this physiological disorder [3]. Studies have shown that blackhearted tissues exhibit substantially increased absorption coefficients (μa) in the 550-850 nm range and elevated reduced scattering coefficients (μ's) across the entire Vis-NIR region compared to healthy tissues [3].

MC simulations of light propagation in these tissues demonstrated that both photon packet weight and penetration depth were significantly lower in blackhearted tissues, with healthy tissues achieving approximately 6.73 mm penetration at 805 nm compared to only 1.30 mm in blackhearted tissues [3]. The simulated absorption energy was higher in blackhearted tissues at both 490 nm and 805 nm, suggesting these wavelengths are particularly effective for blackheart detection [3]. These findings were leveraged to develop Support Vector Machine Discriminant Analysis (SVM-DA) models that achieved 95.83-100.00% accuracy in cross-validation sets, confirming the robustness of optical features for reliable blackheart detection [3].

Case Study 2: Orah Mandarin Quality Assessment

Another agricultural application involves using MC simulations to optimize quality assessment of orah mandarins using Vis/NIR spectroscopy in diffuse reflection mode [7]. As a multi-layered fruit with thick skin, the optical properties of different tissue layers (oil sac layer, albedo layer, and pulp tissue) significantly affect quality evaluation signals.

Researchers measured the optical parameters of each tissue layer using a single integrating sphere system with the IAD method and established a three-layer concentric sphere model for MC simulations [7]. The simulations revealed that light was primarily absorbed within the fruit tissue, with transmitted photons accounting for less than 4.2% of the total [7]. As the source-detector distance increased, the contribution rates of the outer layers (oil sac and albedo) decreased while the pulp tissue contribution increased, leading to the recommendation of a 13-15 mm source-detector distance for optimal detection devices that maintain high pulp signal contribution while obtaining sufficient diffuse reflectance strength [7].

Case Study 3: Photodynamic Therapy Treatment Planning

In clinical medicine, MC simulations have been implemented for treatment planning in photodynamic therapy (PDT), where accurate modeling of light propagation is essential for determining the light dose delivered to both target tissues and surrounding normal structures [2]. Researchers have developed MC modeling spaces that represent complex, three-dimensional samples based on patient CT images, incorporating various fiber geometries including physically accurate representations of cylindrical diffusing fibers used for interstitial PDT [2].

These GPU-accelerated MC implementations enable near real-time simulation of light distribution in patient-specific anatomy, significantly improving treatment planning capabilities for conditions such as head and neck cancer [2]. This application demonstrates the critical importance of accurate light propagation models for ensuring therapeutic efficacy while minimizing damage to healthy tissues.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Tissue Property Determination

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Integrating Sphere | Collects and integrates reflected or transmitted light | 36 mm diameter, PTFE coating (R ≈ 0.90), 9 mm sample port |

| Halogen Lamp Source | Provides broadband illumination for spectral measurements | 150 W adjustable power, 400-1000 nm range |

| Vis-NIR Spectrometer | Measures intensity of light at different wavelengths | USB2000+, 400-1000 nm range |

| Colorimeter | Quantifies tissue color in standardized color space | CIE Lab* color space, measures L, a, b* values |

| Scanning Electron Microscope | Analyzes tissue microstructure at high resolution | Zeiss Sigma 300, requires gold sputter coating of samples |

The study of light-tissue interactions through the fundamental mechanisms of absorption, scattering, and anisotropy provides the essential foundation for advancing both diagnostic and therapeutic applications in biomedical optics. Monte Carlo simulation stands as the gold standard for modeling these complex interactions, offering unparalleled accuracy in predicting light distribution in heterogeneous tissue geometries that defy analytical solutions. The continued development of efficient MC implementations, including GPU-accelerated algorithms and specialized approaches for tissues with specific microstructural characteristics, promises to further expand the applications of these modeling techniques across medical and agricultural domains.

As optical technologies continue to evolve, the integration of accurate light propagation models with patient-specific anatomical data and real-time monitoring capabilities will enable increasingly sophisticated applications in areas ranging from cancer therapy to functional brain imaging. The fundamental principles of light-tissue interactions—governed by the interplay of absorption, scattering, and anisotropy—will remain central to these advances, providing the theoretical framework through which light-based technologies can be optimized for specific clinical and research applications.

The Radiative Transfer Equation (RTE) as the Theoretical Foundation

The Radiative Transfer Equation (RTE) is the fundamental integro-differential equation that describes the propagation of electromagnetic radiation through a medium that absorbs, emits, and scatters energy [8]. It serves as the cornerstone for modeling light transport in various fields, including astrophysics, atmospheric science, and crucially, biomedical optics where it enables the quantitative analysis of light interaction with biological tissues [8] [9].

The RTE strikes a balance between the complex, exact nature of Maxwell's equations and the practical need for a solvable model. While Maxwell's equations provide a complete electromagnetic description, they are often intractable for modeling light propagation in dense, random media like biological tissue. The RTE, in contrast, offers a robust phenomenological framework that has been shown to be a corollary of statistical electromagnetics, bridging the gap between fundamental physics and practical application [9].

In the context of biomedical optics, the RTE provides the theoretical basis for predicting how light energy distributes in tissue, which is essential for developing diagnostic and therapeutic technologies such as photodynamic therapy, diffuse optical tomography, and optical coherence tomography [10] [2]. Its solution enables researchers to relate measurable optical signals (e.g., reflectance, transmittance) to the intrinsic optical properties of tissue, thereby forming the foundation for many inverse problems in medical imaging.

Mathematical Formulation of the RTE

The RTE describes the change in spectral radiance, ( I_\nu(\mathbf{r}, \hat{\mathbf{n}}, t) ), at a point ( \mathbf{r} ), in the direction ( \hat{\mathbf{n}} ), at time ( t ), and for a frequency ( \nu ). This quantity represents the amount of energy flowing through a unit area, per unit time, per unit solid angle, per unit frequency interval [8]. The general form of the time-dependent RTE is given by:

[ \frac{1}{c} \frac{\partial I\nu}{\partial t} + \hat{\Omega} \cdot \nabla I\nu + (\kappa{\nu,s} + \kappa{\nu,a}) \rho I\nu = j\nu \rho + \frac{\kappa{\nu,s} \rho}{4\pi} \int{\Omega} I_\nu d\Omega ]

Here, ( c ) is the speed of light, ( \kappa{\nu,s} ) and ( \kappa{\nu,a} ) are the scattering and absorption coefficients per unit mass, respectively, ( \rho ) is the density of the medium, and ( j_\nu ) is the emission coefficient per unit mass [8]. The integral term on the right-hand side accounts for in-scattering of radiation from all other directions into the direction of interest ( \hat{\mathbf{n}} ).

For many steady-state biomedical applications, the time-independent form of the RTE is sufficient. The single-speed, time-independent version can be written as [11]:

[ \Omega \cdot \nabla \Psi(\mathbf{r}, \Omega) + \sigmat(\mathbf{r}) \Psi(\mathbf{r}, \Omega) = \sigmas(\mathbf{r}) \int_{S^2} \Psi(\mathbf{r}, \Omega') p(\mathbf{r}, \Omega \leftarrow \Omega') d\Omega' + Q(\mathbf{r}, \Omega) ]

In this formulation, ( \Psi(\mathbf{r}, \Omega) ) is the radiation intensity at point ( \mathbf{r} ) in direction ( \Omega ), ( \sigmat ) is the total interaction coefficient (( \sigmat = \sigmas + \sigmaa )), ( \sigmas ) and ( \sigmaa ) are the scattering and absorption coefficients, ( p ) is the scattering phase function, and ( Q ) is the internal radiation source.

Table 1: Key Variables in the Radiative Transfer Equation

| Symbol | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

| ( I_\nu ), ( \Psi ) | Spectral radiance / Radiation intensity | ( W \cdot m^{-2} \cdot sr^{-1} ) |

| ( \sigmaa ), ( \kappa{\nu,a} ) | Absorption coefficient | ( m^{-1} ) |

| ( \sigmas ), ( \kappa{\nu,s} ) | Scattering coefficient | ( m^{-1} ) |

| ( \sigma_t ) | Total interaction coefficient (( \sigmaa + \sigmas )) | ( m^{-1} ) |

| ( p ) | Scattering phase function | ( sr^{-1} ) |

| ( g ) | Scattering anisotropy factor | Dimensionless |

The Scattering Phase Function and Anisotropy

The scattering phase function ( p(\mathbf{r}, \Omega \leftarrow \Omega') ) describes the probability that radiation coming from direction ( \Omega' ) is scattered into direction ( \Omega ). In biological tissues, scattering is typically anisotropic, meaning it is not uniform in all directions. The Henyey-Greenstein phase function is commonly used to model this anisotropy in tissue optics [10]:

[ p(\cos \theta) = \frac{1}{4\pi} \frac{1 - g^2}{(1 + g^2 - 2g \cos \theta)^{3/2}} ]

where ( \theta ) is the scattering angle, and ( g ) is the anisotropy factor, which ranges from -1 (perfect backscattering) to 1 (perfect forward scattering). For most biological tissues, ( g ) ranges from 0.7 to 0.99, indicating strongly forward-directed scattering [10].

The RTE-Monte Carlo Connection

The Monte Carlo (MC) method provides a powerful computational approach for solving the RTE when analytical solutions are intractable. Rather than seeking a closed-form solution, MC simulations model photon transport as a random walk process, statistically simulating the individual interactions of photons with the medium based on the same fundamental optical properties that appear in the RTE [10].

Each photon or photon packet is tracked as it undergoes absorption, scattering, and boundary interactions according to probability distributions derived directly from the RTE's coefficients. The equivalence between the MC approach and the RTE is well-established; MC is essentially a statistical method for solving the RTE by simulating the underlying physical processes it describes [10] [12].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between the RTE and Monte Carlo simulations, and how they form the foundation for applications in biomedical optics:

The diagram above shows how the RTE provides the theoretical foundation for understanding light propagation in tissue, while the Monte Carlo method offers a numerical approach to solve the RTE, together enabling various biomedical applications.

Advantages of Monte Carlo for Biomedical Applications

Monte Carlo simulations offer several distinct advantages for modeling light transport in biological tissues:

Accuracy: MC methods can be made arbitrarily accurate by increasing the number of photons traced, often making them the "gold standard" against which other methods are compared [10] [11].

Flexibility: MC can handle complex, heterogeneous geometries (e.g., layered tissues, blood vessels) and arbitrary boundary conditions that would be intractable for analytical RTE solutions [2].

Comprehensive Data Collection: Simulations can simultaneously track multiple physical quantities (e.g., absorption distribution, fluence rate, pathlength) with any desired spatial and temporal resolution [10].

The main limitation of conventional MC methods is their computational expense, though recent advances in variance reduction techniques, GPU acceleration, and hybrid methods have significantly improved efficiency [11] [2].

Monte Carlo Implementation: From RTE to Practice

Translating the RTE into a practical Monte Carlo simulation involves converting the continuous equation into a discrete stochastic model. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a typical MC simulation for photon transport in tissue:

Key Implementation Steps

Photon Initialization: Photon packets are launched with specific initial positions, directions, and weights (typically set to 1). For a pencil beam incident perpendicular to a tissue surface, initialization would be [10]:

- Position: ( x=0, y=0, z=0 )

- Direction cosines: ( \mux=0, \muy=0, \mu_z=1 )

Step Size Selection: The distance a photon travels between interactions is sampled from the probability distribution derived from Beer-Lambert's law [10]: [ s = -\frac{\ln \xi}{\mut} ] where ( \xi ) is a uniformly distributed random number in (0,1], and ( \mut = \mua + \mus ) is the total attenuation coefficient.

Absorption and Weight Update: At each interaction site, a fraction of the photon weight is absorbed [10]: [ \Delta W = \frac{\mua}{\mut} W ] The remaining weight continues propagating: ( W \leftarrow W - \Delta W ).

Scattering: A new propagation direction is calculated by sampling the scattering phase function. For the Henyey-Greenstein phase function, the scattering angle θ is determined by [10]: [ \cos \theta = \frac{1}{2g} \left[ 1 + g^2 - \left( \frac{1-g^2}{1-g+2g\xi} \right)^2 \right] \quad \text{if} \quad g \neq 0 ] The azimuthal angle φ is uniformly distributed: ( \varphi = 2\pi\xi ).

Advanced Monte Carlo Techniques

To address the computational challenges of conventional MC methods, several advanced techniques have been developed:

Variance Reduction: Methods like implicit capture (photon packets rather than individual photons) and importance sampling significantly improve efficiency without sacrificing accuracy [10] [11].

Accelerated Convergence: New algorithms that couple forward and adjoint RTE solutions can achieve geometric convergence, offering orders-of-magnitude improvement in computational efficiency [11].

GPU Parallelization: Implementing MC algorithms on graphics processing units enables near real-time simulation for complex geometries, making clinical applications feasible [2].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Validating MC simulations against experimental measurements is crucial for establishing their reliability in biomedical applications. The following protocol outlines a typical validation approach using tissue-simulating phantoms:

Phantom Preparation and Experimental Setup

Phantom Fabrication: Create tissue-simulating phantoms with known optical properties using materials such as:

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as a base matrix

- Titanium dioxide or polystyrene microspheres as scattering agents

- India ink or other dyes as absorbing agents [13]

Optical Property Characterization: Independently measure the absorption coefficient ((\mua)), scattering coefficient ((\mus)), and anisotropy factor ((g)) of the phantom using techniques such as:

- Integrating sphere measurements

- Inverse adding-doubling method

- Spatial frequency domain imaging

Experimental Measurement: Set up the optical system (e.g., fiber-based spectrometer, optical coherence tomography system) to measure light transport through the phantom, recording parameters such as:

- Diffuse reflectance

- Transmittance

- Fluence rate distribution [13]

Simulation Parameters and Comparison

MC Simulation Setup: Configure the MC simulation with the measured optical properties and matching source-detector geometry.

Photon Count: Simulate a sufficient number of photon packets (typically (10^6)-(10^9)) to achieve acceptable statistical uncertainty.

Validation Metrics: Compare simulation results with experimental measurements using:

- Root mean square error (RMSE)

- Coefficient of determination (R²)

- Visual comparison of spatial/temporal distributions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Typical Concentrations |

|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Tissue-simulating base matrix | N/A (bulk material) |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Scattering agent | 0.1-2% by weight |

| Polystyrene Microspheres | Controlled scattering particles | 0.5-3% suspension |

| India Ink | Absorption agent | 0.001-0.1% by volume |

| Nylon Fibers | Raman scattering target | Varies with application |

| Intralipid | Commercial scattering standard | 1-20% dilution |

Applications in Tissue Research and Drug Development

The RTE-based Monte Carlo approach has enabled significant advances in numerous biomedical applications:

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) Planning

MC simulations of light propagation allow clinicians to optimize light dose delivery for PDT. By modeling the specific anatomy of a patient (derived from CT or MRI scans), clinicians can calculate the fluence rate distribution throughout the treatment volume, ensuring that therapeutic light levels reach the target tissue while minimizing exposure to healthy structures [2]. This approach has been successfully applied for treatment planning in head and neck cancers, significantly improving treatment efficacy.

Surgical Guidance with Raman Spectroscopy

MC methods help establish the relationship between Raman sensing depth and tissue optical properties, which is crucial for interpreting spectroscopic data during surgery. Studies have shown that for a typical Raman probability of (10^{-6}), the sensing depth ranges between 10 and (600 \mu m) for absorption coefficients of 0.001 to (1.4 mm^{-1}) and reduced scattering coefficients of 0.5 to (30 mm^{-1}) [13]. This quantitative understanding enables more precise biopsy collection and tumor margin assessment.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

MC simulations of OCT systems incorporate wave-based phenomena like coherence and interference, providing a bridge between the particle-based RTE and the wave nature of light. Recent advances include modeling focusing Gaussian beams rather than infinitesimally thin beams, leading to more accurate simulations of modern OCT systems [14]. These simulations help solve inverse problems to extract tissue optical properties from OCT measurements.

Drug Development Applications

In pharmaceutical research, MC simulations support several critical activities:

Photosensitizer Dosimetry: Calculating light doses for activating photodynamic therapy agents in specific tissue geometries.

Treatment Planning: Optimizing light delivery systems for activating light-sensitive drug compounds.

Monitoring Therapeutic Response: Modeling changes in tissue optical properties resulting from treatment, which can serve as biomarkers of efficacy.

The Radiative Transfer Equation provides the essential theoretical foundation for understanding and modeling light transport in biological tissues. While the RTE itself is often analytically intractable for realistic tissue geometries, Monte Carlo methods offer a powerful, flexible, and accurate approach for solving it numerically. The synergy between the rigorous theoretical framework of the RTE and the practical computational capabilities of MC simulations has enabled significant advances in biomedical optics, particularly in therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Ongoing research continues to enhance this partnership, with developments in accelerated convergence algorithms, GPU implementation, and more sophisticated models of tissue optics further strengthening the connection between theory and application. As these methods become more efficient and accessible, their impact on clinical practice and drug development is expected to grow, ultimately improving patient care through more precise optical-based therapies and diagnostics.

The propagation of light through biological tissue is governed by the Radiative Transfer Equation (RTE), a differential equation that describes the balance of energy as photons travel through, are absorbed by, and are scattered within a medium. For complex, heterogeneous geometries like human tissue, obtaining analytical solutions to the RTE is often impossible. The Monte Carlo (MC) method provides a powerful, flexible, and rigorous alternative by simulating the stochastic propagation of individual photons [10]. Instead of solving the RTE directly, MC models the local rules of photon transport as probability distributions, effectively tracing the random walks of millions of photons to build a statistically accurate picture of light distribution [10]. This technique is widely considered the gold standard for simulating light transport in tissues, particularly for biomedical applications such as photodynamic therapy, diffuse optical tomography, and radiation therapy planning [15] [10]. This guide details the core principles and practical implementation of the Monte Carlo method for solving the RTE, with a specific focus on applications in tissue research.

Theoretical Foundation: Linking Stochastic Sampling to the RTE

The fundamental principle of the Monte Carlo method for light transport is its equivalence to the RTE. The RTE itself describes the change in radiance, a measure of light energy, at a point in space and in a specific direction [16]. The MC approach stochastically models the same physical phenomena—the step size between photon interactions (absorption and scattering events) and the scattering angle when a deflection occurs [10].

The core of the method lies in interpreting the photon's history as a random walk, where each step is determined by sampling from probability distributions derived from the tissue's optical properties [17] [10]. These properties are:

- The Absorption Coefficient (µa): The probability of photon absorption per unit path length.

- The Scattering Coefficient (µs): The probability of photon scattering per unit path length.

- The Scattering Phase Function: The probability distribution of the scattering angle, θ, often characterized by the anisotropy factor, g, which is the weighted average of the cosine of the scattering angle [10].

When a sufficient number of photon packets are simulated, their collective behavior converges to the solution of the RTE. This makes MC a robust, albeit computationally intensive, method that can achieve arbitrary accuracy by increasing the number of photons traced, without the simplifying assumptions required by analytical models [10].

Table 1: Key Optical Properties and Their Roles in Monte Carlo Simulation

| Optical Property | Symbol | Role in Monte Carlo Simulation | Typical Values in Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient | µₐ | Determines the fraction of photon weight absorbed at each interaction site. | Varies widely by wavelength and tissue type |

| Scattering Coefficient | µₛ | Inversely related to the mean free path between scattering events. | ~10-100 mm⁻¹ (highly tissue-dependent) |

| Anisotropy Factor | g | Describes the preferential direction of scattering; g=1 is forward, g=0 is isotropic. | 0.7 - 0.9 for most tissues [18] |

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient | µₛ' = µₛ(1-g) | A derived property useful in diffusion theory; represents the effective scattering after considering anisotropy. | Calculated from µₛ and g |

A Practical Implementation: The Photon Transport Algorithm

A typical MC simulation for a homogeneous medium involves launching photon packets and repeatedly subjecting them to a cycle of movement, absorption, and scattering until they exit the geometry or are terminated. The following workflow, detailed in [10], outlines this core algorithm.

Step 1: Launching a Photon Packet

To improve computational efficiency, photons are often grouped into packets with an initial weight, W, typically set to 1. The initial position and direction (defined by three direction cosines) are set based on the light source. For a pencil beam at the origin, perpendicular to the surface, the initialization is [10]:

- Position: ( x=0, y=0, z=0 )

- Direction Cosines: ( \mux=0, \muy=0, \mu_z=1 )

Step 2: Step Size Selection and Photon Movement

The distance, ( s ), a photon travels before an interaction is a random variable determined by the total interaction coefficient, ( \mut = \mua + \mus ), which represents the probability of any interaction per unit path length. The step size is sampled using [10]: [ s = -\frac{\ln \xi}{\mut} ] where ( \xi ) is a random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. The photon's coordinates are then updated: [ x \leftarrow x + \mux s, \quad y \leftarrow y + \muy s, \quad z \leftarrow z + \mu_z s ]

Step 3: Absorption and Scattering

At the interaction site, a fraction of the photon's weight is absorbed. This fraction is ( \Delta W = (\mua / \mut) W ). The remaining weight is scattered in a new direction [10]. The new direction is determined by the scattering phase function. The Henyey-Greenstein phase function is commonly used for tissue due to its accuracy and computational simplicity. The scattering angle, θ, and a uniformly sampled azimuthal angle, φ, are calculated [10]: [ \cos \theta = \frac{1}{2g} \left[ 1 + g^2 - \left( \frac{1-g^2}{1-g+2g\xi} \right)^2 \right] \quad ( \text{for } g \neq 0 ) ] [ \varphi = 2\pi\xi ] The photon's direction cosines are then updated based on these angles, and the cycle repeats from Step 2. A photon packet is terminated when its weight falls below a threshold, or it exits the simulated geometry.

Advanced Techniques: Condensed History for Accelerated Simulation

In biological tissue, scattering is often highly forward-peaked (g > 0.7), meaning photons undergo thousands of small-angle deflections per millimeter of travel [18]. Simulating each of these collisions individually in a "collision-by-collision" approach is computationally expensive. Condensed History (CH) methods address this by grouping multiple scattering events into a single "super-event," dramatically speeding up simulations with minimal loss of accuracy [18].

Two prominent CH models are:

- Similarity Theory (ST) Model: This model simplifies the problem by using an isotropic scattering phase function but with modified, lower scattering and absorption coefficients to preserve the overall transport characteristics [18].

- Discrete Scattering Angles (DSA) Model: This more sophisticated approach approximates the highly forward-peaked scattering phase function (e.g., Henyey-Greenstein) with a linear combination of delta functions. This method is designed to preserve the low-order angular moments of the original phase function, leading to higher accuracy than the ST model for a wide range of tissue optical properties [18].

Essential Computational Tools and Platforms

The computational demand of MC simulations has led to the development of specialized software platforms. The table below summarizes key tools used across different application scales in biomedical optics and therapy planning.

Table 2: Key Monte Carlo Simulation Platforms in Biomedical Research

| Platform Name | Primary Application Domain | Key Features & Strengths | Underlying Language/Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGSnrc | Radiation therapy dose calculation; Nanoparticle dose enhancement [15] | Electron and photon transport; Open-source; Customizable material files. | C++ |

| Geant4 | General purpose particle transport; Nanoparticle-enhanced radiotherapy [15] [19] | Models full Auger de-excitation cascades; Broad physics processes. | C++ |

| GPU-Accelerated Codes (e.g., gDRR, GGEMS) | Transmission & emission tomography (CT, PET, SPECT) [19] | Extreme speedups (100-1000x over CPU); Enables practical, large-scale applications. | CUDA, OpenCL |

| Custom MCML & Derivatives | Light transport in multi-layered tissues (historical and specialized use) | Standardized model for layered media; Extensive validation. | C |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation and application of Monte Carlo models in tissue research require a combination of software and conceptual "reagents."

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Monte Carlo Studies

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Henyey-Greenstein Phase Function | A mathematical function that models the angular distribution of single scattering events in biological tissue. | Serves as the scattering phase function for sampling new photon directions after a scattering event [10]. |

| Variance Reduction Techniques | Methods to decrease the statistical noise of the simulation without increasing the number of photon packets. | Using photon packets with weights instead of individual photons is a primary variance reduction technique [10]. |

| Digital Tissue Phantom | A computer model that defines the 3D geometry and spatial distribution of optical properties within a simulated tissue. | Used as the virtual environment in which photon packets propagate; can be simple slabs or complex, anatomically accurate models. |

| GPU Parallelization | The use of graphics processing units (GPUs) to run thousands of photon histories in parallel, drastically reducing computation time. | Essential for simulating large tissue volumes or obtaining high-precision results in a reasonable time frame [19]. |

| Optical Property Library | A curated database of the absorption and scattering coefficients (µₐ, µₛ) and anisotropy (g) for various tissue types at specific wavelengths. | Provides the critical input parameters that define how the simulated virtual tissue interacts with light. |

Applications in Biomedical Research and Therapeutics

The MC method's flexibility makes it indispensable in several advanced biomedical applications:

- Photodynamic Therapy (PDT): MC simulations model the light fluence distribution within tissue to ensure sufficient activating light reaches the target area, enabling precise dosimetry for effective treatment [10].

- Diffuse Optical Tomography (DOT): In this imaging technique, MC serves as the "forward model," predicting how light from a source will travel through tissue to reach a detector. This model is essential for reconstructing images of internal optical properties [10].

- Nanoparticle-Enhanced Radiotherapy: MC simulations, particularly using platforms like Geant4, are critical for calculating the Dose Enhancement Factor (DEF) when heavy nanoparticles like gold are introduced into tumor cells. They track the secondary electrons and photons released upon irradiation, providing a more complete picture of local energy deposition than analytical methods [15].

- Sensor and ADAS Development: Physically-based simulators like the SWEET platform use MC techniques to test and validate optical sensors (cameras, lidars) for autonomous vehicles by replicating their performance in adverse weather conditions like fog [16].

The Monte Carlo method provides a powerful and fundamentally rigorous framework for solving the Radiative Transfer Equation in complex, scattering-dominated media like biological tissue. By translating a deterministic differential equation into a stochastic process of photon trajectory sampling, it achieves a level of accuracy and flexibility that is difficult to match with purely analytical approaches. While computationally demanding, modern advancements, including GPU acceleration and sophisticated condensed history algorithms, continue to expand its practicality and scope. For researchers in optics, drug development, and therapeutic planning, mastering the Monte Carlo method is not merely an academic exercise but a critical tool for advancing the precision and efficacy of light-based technologies in medicine.

In the field of biomedical optics, the interaction of light with biological tissue is governed by a set of fundamental optical properties. Understanding these properties—the absorption coefficient (μa), the scattering coefficient (μs), and the anisotropy factor (g)—is paramount for advancing research in therapeutic and diagnostic applications, particularly when employing sophisticated modeling techniques like Monte Carlo simulations for light propagation in tissue. These parameters form the core of the radiative transfer equation (RTE), the fundamental mathematical model for describing photon transport in turbid media like biological tissue [20]. Accurately determining these properties enables researchers to predict how light will distribute within tissue, which is essential for developing both light-based therapies and diagnostic technologies.

This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core properties, framed within the context of computational modeling. A precise understanding of μa, μs, and g is not merely academic; it is the foundation for constructing accurate and predictive Monte Carlo models that can simulate light-tissue interactions in silico, thereby reducing the need for extensive and costly laboratory experiments [20] [21].

Defining the Core Optical Properties

The propagation of light through biological tissue is a complex process of absorption and scattering. The following properties quantitatively describe these interactions.

Absorption Coefficient (μa)

- Definition: The absorption coefficient (μa) defines the probability of a photon being absorbed per unit path length within a medium. It is measured in inverse centimeters (cm⁻¹) [20] [21].

- Physical Interpretation: A higher μa value indicates a greater likelihood of photon absorption. This coefficient is directly proportional to the concentration of absorbing chromophores within the tissue, such as hemoglobin, melanin, and water [21]. The absorption process converts light energy into other forms, such as heat or chemical energy.

- Role in the RTE: In the radiative transfer equation, the term

-μa * L(r, ŝ)represents the loss of radiance due to absorption [20]. - Dependence: The absorption coefficient μa typically exhibits a linear dependence on the concentration of the absorbing chromophore, even in highly dense media [22].

Scattering Coefficient (μs)

- Definition: The scattering coefficient (μs) defines the probability of a photon being scattered per unit path length within a medium. It is also measured in inverse centimeters (cm⁻¹) [20] [21].

- Physical Interpretation: Scattering redirects a photon's path without a loss of energy. The value of μs indicates the density of scattering particles in the tissue. Biological tissues are typically high-scattering media, meaning photons undergo numerous scattering events before being either absorbed or exiting the tissue.

- Role in the RTE: In the RTE, scattering contributes to both energy loss and gain. The term

-μs * L(r, ŝ)represents loss from the primary beam due to scattering away from directionŝ, while the integral term+ μs * ∫ p(ŝ, ŝ') L(r, ŝ') dΩ'represents the gain from light scattered from all other directionsŝ'into directionŝ[20].

Anisotropy Factor (g)

- Definition: The anisotropy factor (g) describes the average direction in which light is scattered during a single scattering event. It is defined as the mean cosine of the scattering angle θ [20].

- Physical Interpretation and Values: This is a dimensionless parameter ranging from -1 to +1.

- Role in the RTE: The anisotropy g is a key parameter of the scattering phase function,

p(ŝ, ŝ'), which describes the angular distribution of scattered light [20]. The Henyey-Greenstein phase function is commonly used in tissue optics to model this angular dependence [23].

The Reduced Scattering Coefficient (μs')

While not a fundamental property, the reduced scattering coefficient is a critical derived parameter for modeling light propagation in the diffusion regime.

- Definition:

μs' = μs * (1 - g)[cm⁻¹] [24]. - Purpose and Utility: It combines the scattering coefficient (μs) and the anisotropy (g) into a single parameter that describes the effectiveness of scattering in randomizing the direction of photon propagation. It represents the scattering coefficient that would be observed if all scattering events were isotropic (g=0). This parameter is essential for models that use the diffusion approximation of the RTE, as it defines the random walk step size of photons (

1/μs') in a predominantly scattering medium (whereμa << μs') [20] [24].

Table 1: Summary of Key Optical Properties and Their Roles

| Property | Symbol | Units | Definition | Role in Light Transport |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient | μa | cm⁻¹ | Probability of absorption per unit path length | Determines energy deposition and attenuation. |

| Scattering Coefficient | μs | cm⁻¹ | Probability of scattering per unit path length | Determines how frequently a photon's path is redirected. |

| Anisotropy Factor | g | Dimensionless | Mean cosine of the scattering angle | Determines the preferred direction of scattering (forward/backward). |

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient | μs' | cm⁻¹ | μs' = μs(1 - g) | Governs the rate of directional randomization in dense scattering media. |

Mathematical Relationships and Light Transport Models

The interplay between the optical properties is formally captured by mathematical models of increasing complexity, from the exact but computationally expensive RTE to its simplified diffusion approximation.

The Radiative Transfer Equation (RTE)

The RTE is the most rigorous model for light propagation in a scattering and absorbing medium. It describes the change in radiance L(r, ŝ, t) at a position r, in direction ŝ, and at time t. The general form of the time-dependent RTE is [20]:

Where:

cis the speed of light in the medium.μ_t = μ_a + μ_sis the extinction coefficient.p(ŝ, ŝ')is the scattering phase function.S(r, ŝ, t)is the light source term.- The integral is over the

4πsolid angle.

The RTE states that the radiance in a specific direction changes due to (1) the spatial divergence of the beam, (2) loss from extinction (absorption and scattering away from ŝ), (3) gain from scattering from all other directions ŝ' into ŝ, and (4) the contribution from the light source [20].

The Diffusion Approximation

Solving the RTE is computationally challenging due to its high dimensionality. For media where scattering dominates absorption (μ_a << μ_s') and light distribution becomes nearly isotropic after many scattering events, the diffusion approximation offers a simpler, yet powerful, alternative.

The derivation involves expanding the radiance in spherical harmonics and retaining only the isotropic and first-order anisotropic terms [20]:

Here, Φ(r, t) is the fluence rate and J(r, t) is the current density. Substituting this into the RTE leads to two simplified equations. The vector form yields Fick's law, which defines the current density in terms of the gradient of the fluence rate [20]:

Where D is the diffusion coefficient, defined as D = 1 / (3(μ_a + μ_s')) or, more precisely, D = 1 / (3(μ_a + (1-g)μ_s)) [20].

Substituting Fick's law into the scalar form of the approximated RTE gives the diffusion equation [20]:

This equation is significantly easier to solve than the RTE and is accurate in regions far from light sources or boundaries, where the radiance is indeed nearly isotropic.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the optical properties, the RTE, and its approximations, culminating in the Monte Carlo solution.

Diagram 1: Relationship between optical properties and light transport models. Monte Carlo can model both the full RTE and validate diffusion theory.

Experimental Determination of Optical Properties

Accurately measuring μa, μs, and g is a central challenge in tissue optics. The methods generally involve measuring light signals after interaction with a sample and solving an "inverse problem" to deduce the properties.

Integrating Sphere-Based Techniques

The traditional and most established method involves using one or two integrating spheres to measure the total diffuse reflectance (Rd) and total diffuse transmittance (Td) of a tissue sample [23] [21].

- Procedure: A collimated light beam is incident on a sample. An integrating sphere collects all light diffusely reflected from the sample surface, while another (if used) collects all light diffusely transmitted through the sample. A third measurement of collimated transmittance (

Tc) through a thin sample is often used to determine the extinction coefficientμ_tdirectly via the Beer-Lambert law [23]. - Inverse Problem: The measured

RdandTdare compared to the values calculated by a forward model (e.g., Adding-Doubling method, Inverse Monte Carlo) for a given set ofμa,μs, andg. An iterative process is used to find the set of optical properties that minimizes the difference between measured and calculatedRdandTd[23] [21].

Advanced Non-Hemispherical Methods

Recent research focuses on developing methods that do not require bulky and complex integrating spheres.

- Principle: This approach uses a combination of non-hemispherical reflectance (

Rd), transmittance (Td), and forward transmittance (Tf) signals, measured with detectors placed close to the sample [23]. - Advantages: The

Tfsignal, which is dominated by single-scattering and ballistic photons, allows for the characterization of optically thick samples where collimated transmittance (Tc) is too weak to measure. Using multiple signals with different sensitivities to scattering and absorption (e.g.,Tfis sensitive to single scattering, whileRdis dominated by multiple scattering) improves the stability and uniqueness of the inverse solution forμa,μs, andg[23]. - Inverse Solution: As with sphere-based methods, the measured signals are compared to those calculated by a forward model (which must accurately account for boundary conditions and detector geometry) to retrieve the optical properties [23].

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Methods for Determining Optical Properties

| Method | Measured Signals | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Typical Forward Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual Integrating Sphere | Total Diffuse Reflectance (Rd), Total Diffuse Transmittance (Td), often with Collimated Transmittance (Tc) | Gold standard; captures all diffuse light. | Complex setup; requires thin samples for Tc; time-consuming. | Adding-Doubling, Inverse Monte Carlo |

| Non-Hemispherical Multi-Signal | Non-hemispherical Rd, Td, and Forward Transmittance (Tf) | Can use a single, optically thick sample; more accessible instrumentation. | Requires precise modeling of detector geometry and boundaries. | Monte Carlo, Approximate RTE solvers |

The following diagram outlines the general workflow for an inverse method to determine optical properties, common to both approaches.

Diagram 2: Generalized workflow for inverse determination of optical properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Experimental work in tissue optics relies on a set of key materials and instruments. The following table details essential items used in the field, particularly for experiments aimed at determining optical properties.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Instruments

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Tissue Phantoms | Synthetic samples that mimic the optical properties of biological tissue. Often made from materials like Intralipid (scatterer) and ink or dyes (absorber). Used for calibration and validation of instruments and models [23] [22]. |

| Integrating Spheres | Hollow spherical devices with a highly reflective interior coating. Used to collect and homogenize all light diffusely reflected from or transmitted through a sample, allowing for a total power measurement [23]. |

| Tunable Light Source / Monochromator | A light source (e.g., a Xenon lamp) coupled with a monochromator to produce monochromatic light at specific wavelengths. Essential for performing spectral measurements to determine how μa and μs vary with wavelength [23]. |

| Sphere Suspensions (e.g., Polystyrene) | Well-characterized suspensions of microspheres with known size and refractive index. Used as standard scatterers in tissue phantoms and for validating measurement techniques against theoretical predictions like Mie theory [23] [22]. |

| Time-/Frequency-Domain instrumentation | Advanced systems that measure the temporal broadening of a short light pulse or the phase shift of an intensity-modulated beam after propagation through tissue. Provides more information for accurately separating μa and μs' compared to steady-state measurements [21]. |

Connection to Monte Carlo Simulations for Light Propagation

Monte Carlo (MC) simulations are a powerful and versatile numerical technique for modeling photon transport in tissue. Their relationship with the optical properties μa, μs, and g is foundational.

- Direct Implementation of Physics: MC methods simulate the random walk of individual photons as they travel through a medium defined by its optical properties. The probability of a photon being absorbed or scattered over a path length is directly governed by

μaandμs. If a scattering event occurs, the new direction of the photon is determined by the scattering phase function, for whichgis the key parameter (e.g., using the Henyey-Greenstein function) [20] [23]. - Gold Standard for Validation: Because MC simulations make minimal approximations (they can model the RTE exactly with a sufficient number of photons), they are often used as a gold standard to assess the accuracy of simpler models, such as solutions derived from the diffusion equation. As shown in the search results, the diffusion approximation introduces inaccuracies, particularly close to the light source and boundaries where the radiance is not isotropic; MC simulations accurately capture this complexity [20].

- Inverse Monte Carlo: This technique is used to determine optical properties experimentally. An MC model is run iteratively with guessed optical properties until its output (e.g., diffuse reflectance) matches the measured data from a real sample. The properties used in the final, matching simulation are taken to be the optical properties of the sample [21].

In summary, within a thesis on Monte Carlo modeling, the optical properties μa, μs, and g are not merely input parameters; they are the very language in which the tissue geometry and the physics of photon interaction are defined. A deep understanding of their definition, their mathematical relationships, and the experimental methods used to ascertain them is crucial for developing, validating, and interpreting sophisticated computational models of light propagation in biological tissue.

This technical guide details the core probability distributions and methodologies that form the foundation of the Monte Carlo (MC) method for simulating light propagation in biological tissues. Framed within a broader thesis on MC simulation for tissue research, this document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the in-depth knowledge required to implement, understand, and critically evaluate these computational models.

The Monte Carlo method provides a rigorous, flexible approach for simulating photon transport in turbid media by modeling local interaction rules as probability distributions [10]. This approach is mathematically equivalent to solving the Radiative Transfer Equation (RTE) but avoids the simplifications required for analytical solutions, such as the diffusion approximation, which introduces inaccuracies near sources and boundaries [10]. Instead, MC methods track the random walks of individual photons or photon packets as they travel through tissue, with their paths determined by statistically sampling probability distributions for two key parameters: the step size between interaction sites and the scattering angle when a deflection occurs [25] [26]. The accuracy of MC simulations is limited only by the number of photons traced, making them the gold standard for simulated measurements in many biomedical applications, including biomedical imaging, photodynamic therapy, and radiation therapy planning [10] [27].

Core Probability Distributions in Photon Transport

The physical interaction between light and tissue is governed by the tissue's optical properties. The core probability distributions used in MC simulations directly derive from these properties.

The following table summarizes the essential optical properties and their corresponding probability distributions used in MC simulations.

Table 1: Core Optical Properties and Associated Probability Distributions

| Optical Property (Symbol) | Physical Meaning | Corresponding Probability Distribution | Key Sampling Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient (μₐ) | Probability of photon absorption per unit path length [28]. | Not used directly for path sampling; determines weight loss at interaction sites. | ( W \leftarrow W - \left( \frac{\mua}{\mut} \right) W ) [10] |

| Scattering Coefficient (μₛ) | Probability of photon scattering per unit path length [28]. | Used in the step size distribution. | ( s = -\frac{\ln(\xi)}{\mu_t} ) [10] [26] |

| Total Attenuation Coefficient (μₜ) | Probability of an interaction (absorption or scattering) per unit path length; μₜ = μₐ + μₛ [28]. | Step size (s) of a photon between interaction sites [10]. | ( s = -\frac{\ln(\xi)}{\mu_t} ) [10] [26] |

| Anisotropy Factor (g) | Mean cosine of the scattering angle [10]. | Scattering phase function, p(θ, φ), defining deflection angles θ and φ [10]. | ( \cos \theta = \frac{1}{2g}\left[1+g^2-\left( \frac{1-g^2}{1-g+2g\xi} \right)^2 \right] ) (g ≠ 0) [10] |

The Step Size Distribution

The step size, ( s ), is the distance a photon travels between two interaction sites (absorption or scattering events). The probability of a photon having a free path length of at least ( s ) is governed by the Beer-Lambert law, leading to an exponential probability density function (PDF) [10] [26]: [ p(s) = \mut e^{-\mut s} ] where ( \mut = \mua + \mus ) is the total attenuation coefficient. To sample a step size ( s ) from this distribution, the inverse cumulative distribution function (CDF) method is applied. The CDF, ( F(s) ), is integrated and set equal to a random number ( \xi ), uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 [26]: [ F(s) = \int0^s p(s') ds' = 1 - e^{-\mut s} = \xi ] Solving for ( s ) yields the sampling formula: [ s = -\frac{\ln(1-\xi)}{\mut} ] Since ( (1-\xi) ) is statistically equivalent to ( \xi ), the computationally efficient form is: [ s = -\frac{\ln(\xi)}{\mu_t} ]

The Scattering Angle Distributions

When a scattering event occurs, a new photon direction must be selected. This is defined by two angles: the deflection angle (θ) and the azimuthal angle (φ).

- Deflection Angle (θ): The Henyey-Greenstein phase function is most commonly used to model this in biological tissues, as it provides a good empirical match and is parameterized by the anisotropy factor ( g ) [10]. The PDF and its sampling formula are:

[ p(\cos \theta) = \frac{1}{2} \frac{1 - g^2}{(1 + g^2 - 2g \cos \theta)^{3/2}} ] [ \cos \theta = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{2g}\left[1 + g^2 - \left( \frac{1 - g^2}{1 - g + 2g\xi} \right)^2 \right] & \text{if } g \ne 0 \ 1 - 2\xi & \text{if } g = 0 \end{cases} ]

- Azimuthal Angle (φ): This angle is typically assumed to be uniformly distributed between 0 and ( 2\pi ) because scattering is symmetric around the photon's initial direction [10]. It is sampled simply as: [ \varphi = 2\pi\xi ]

After sampling ( \theta ) and ( \varphi ), the new photon direction cosines ( (\mux', \muy', \muz') ) are calculated from the old direction cosines ( (\mux, \muy, \muz) ) using a coordinate transformation [10].

Implementation Workflow for a Basic Monte Carlo Simulation

The following diagram and description outline the core algorithm of a photon packet MC simulation in a homogeneous medium.

Diagram 1: Photon packet life cycle workflow.

Experimental Protocol: Photon Packet Lifecycle

The MC algorithm simulates the propagation of millions of photon packets through a series of repeated steps [10] [26]. The following protocol details this process, corresponding to the workflow in Diagram 1.

Photon Packet Launch

- Initialization: Set the photon's initial coordinates. For a pencil beam at the origin, this is ( x=0, y=0, z=0 ).

- Direction: Initialize the direction cosines. For a beam normal to the surface, this is ( \mux=0, \muy=0, \mu_z=1 ) [10].

- Weight: Assign the photon packet a starting weight, typically ( W = 1 ).

Step Size Selection and Movement

- Sampling: Use the formula ( s = -\ln(\xi)/\mu_t ) to determine the distance to the next interaction site.

- Propagation: Update the photon's position: ( x \leftarrow x + \mux s ), ( y \leftarrow y + \muy s ), ( z \leftarrow z + \mu_z s ) [10].

Absorption and Weight Update

- Energy Deposit: At the interaction site, a fraction of the photon's weight is absorbed. The deposited energy is ( \Delta W = (\mua / \mut) W ).

- Weight Reduction: Update the photon packet weight: ( W \leftarrow W - \Delta W ). The value ( \Delta W ) can be recorded in a spatial array to map the absorption distribution [10].

Scattering and Direction Change

- Angle Sampling: Sample the scattering angle ( \theta ) using the Henyey-Greenstein formula and the azimuthal angle ( \phi ) uniformly.

- Coordinate Transformation: Calculate a new set of direction cosines ( (\mux', \muy', \mu_z') ) based on the sampled angles and the previous direction [10].

Photon Termination

- Russian Roulette: When the photon packet weight drops below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 0.0001), the photon is playing a game of "Russian Roulette." It has a small chance (e.g., 1 in 10) of surviving, in which case its weight is increased by a factor of 10. If it loses, it is terminated [10] [25]. This variance reduction technique saves computation time on photons that contribute little to the final result.

- Boundary Interaction: If the photon packet moves to a boundary, it can be either reflected (based on Fresnel reflections) or transmitted out of the medium, at which point its trajectory is logged, and it is terminated [10].

This section catalogs key computational tools and methodological concepts essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 2: Key Resources for Monte Carlo Simulation in Biomedical Optics

| Resource / Concept | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| MCML [25] | Software Code | A widely adopted, steady-state MC program for simulating light transport in multi-layered tissues. Considered a benchmark in the field. |

| GPU Acceleration [25] [29] | Hardware/Software Technique | Using graphics processing units (GPUs) to run parallelized MC simulations, offering orders-of-magnitude speed improvements. |

| Variance Reduction [10] [27] | Computational Method | Techniques like photon packet weighting and Russian Roulette that reduce statistical noise and computation time without biasing results. |

| Scaling/Perturbation Methods [30] [27] | Computational Method | Advanced algorithms that reuse photon path histories from a baseline simulation to model new scenarios, drastically accelerating studies involving parameter variations. |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) [31] [29] | Computational Method | Deep learning models can act as surrogate models to predict MC-simulated dose distributions or light fluence in seconds, bypassing lengthy computations. |

| GATE/Geant4 [29] | Software Platform | Extensible software toolkits for simulating particle transport, widely used in medical physics for imaging and therapy dosimetry. |

| Tissue Optical Properties (μₐ, μₛ, g, n) [26] | Input Parameters | The critical set of wavelength-dependent parameters that define the simulated tissue's interaction with light. Accuracy here is paramount for meaningful results. |

| Convolution [25] | Post-Processing Technique | A mathematical operation used with MCML outputs to model the response to finite-sized beams of arbitrary shape, rather than just an infinitely narrow pencil beam. |

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

While the core distributions remain unchanged, the field is advancing rapidly to address the computational burden of traditional MC and to tackle more complex biological problems.

Acceleration through Scaling and AI: The significant computation time required for high-accuracy results is a major drawback. Recent research focuses on powerful acceleration algorithms. Scaling methods can achieve a 46-fold improvement in computational time for fluorescence simulations with minimal error [30]. Even more transformative is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), where deep learning models can be trained to predict full MC-simulated dose distributions [31] or light fluence in a fraction of a second, acting as a near-instantaneous surrogate model [29].

Handling Tissue Complexity: Basic models assume homogeneous tissues, but real tissues are structurally complex. Advanced MC codes like