Laser-Tissue Interactions: Fundamentals, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the fundamental principles and modern applications of laser-tissue interactions for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Laser-Tissue Interactions: Fundamentals, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the fundamental principles and modern applications of laser-tissue interactions for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the underlying physical mechanisms including optical properties, thermal effects, and selective photothermolysis. The content details advanced computational modeling approaches, reviews current clinical applications across medical specialties, and analyzes optimization strategies for improving efficacy and safety. Through comparative analysis of laser systems and validation methodologies, this resource serves as both a foundational reference and forward-looking guide to emerging trends in laser-based biomedical technologies.

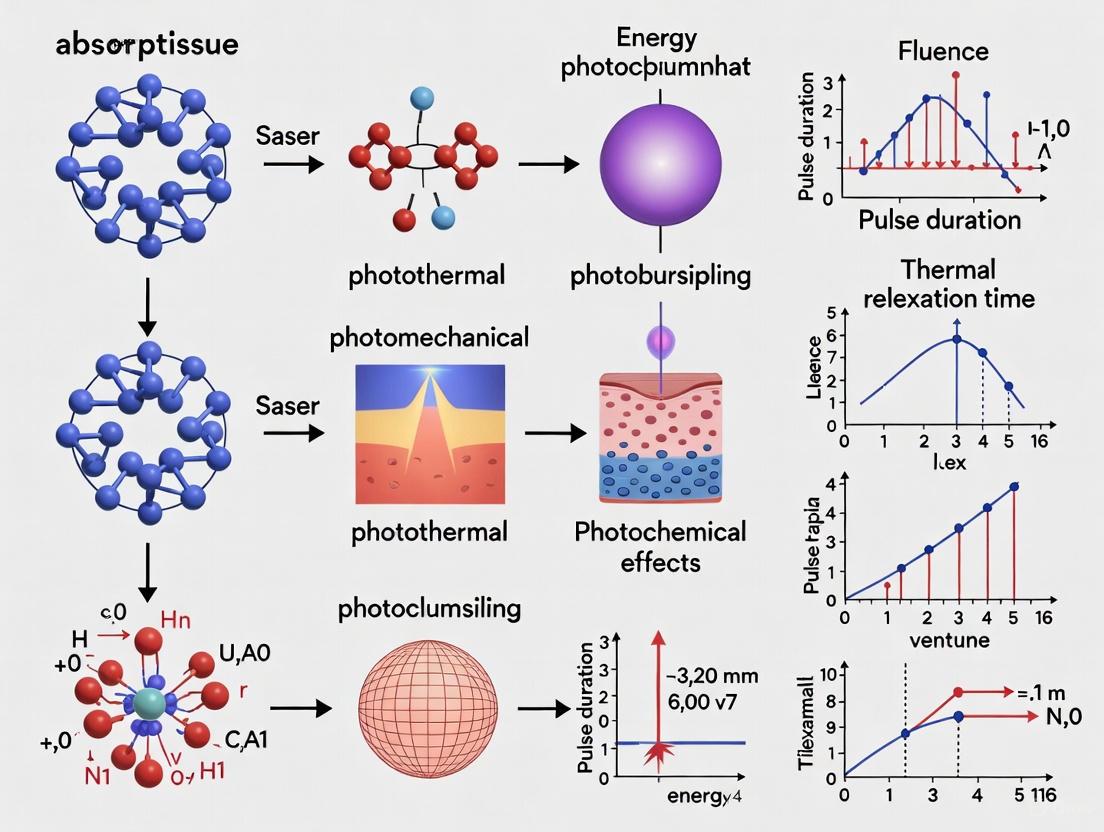

Fundamental Principles of Laser-Tissue Interactions: From Photons to Biological Effects

The interaction between laser light and biological tissue is fundamentally governed by the tissue's optical properties, primarily absorption and scattering. These properties determine how light energy is distributed within tissue, ultimately controlling the efficacy of both diagnostic and therapeutic laser applications in medicine and research. The propagation of light through biological tissues is characterized by absorption and scattering effects; absorption relates to the presence of chromophores (e.g., oxy-hemoglobin, deoxy-hemoglobin, water, lipid, and collagen), while scattering depends on inhomogeneities or fluctuations of the refractive index at the wavelength scale [1]. In the UV and visible spectral ranges, absorption limits light penetration to superficial tissue layers, whereas in the red and near-infrared (NIR) spectral region (approximately 600–1100 nm), known as the "therapeutic window," scattering dominates over absorption, allowing photons to penetrate deeply into tissues [1].

When laser light is applied to tissue, approximately 4–7% of the incident energy is reflected at the air-tissue interface due to the difference in refractive indices [2]. The remaining light may be absorbed by the tissue, transmitted through it, or scattered within it. Absorption refers to how tissues take up light energy, which is then converted into other forms, such as heat, leading to photothermal effects, or triggering photochemical reactions [3] [4]. Scattering causes the photon path to deviate from a straight line, diffusing light into the tissue rather than allowing it to travel in a linear fashion [3]. The combined effect of absorption and scattering determines penetration depth, defined as the depth at which light intensity decreases to 1/e (approximately 37%) of its original surface value [5]. These three factors—absorption, scattering, and penetration—are interrelated; increased scattering or absorption in tissue results in decreased penetration [3].

Understanding these optical properties is crucial for numerous biomedical applications, including photothermal therapy, photodynamic therapy, photobiomodulation, surgical ablation, and diagnostic imaging. This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of the optical properties of biological tissues, with quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and practical resources for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles of Light Transport in Tissue

Key Optical Properties and Their Definitions

The propagation of light in biological tissues is quantitatively described by several key parameters:

- Absorption Coefficient (μₐ): This measures the probability of light absorption per unit path length in the tissue. It is expressed in units of cm⁻¹. A higher μₐ indicates that light is more readily absorbed, limiting its penetration. Absorption is primarily governed by chromophores present in the tissue [6] [1].

- Scattering Coefficient (μₛ): This defines the probability of light scattering per unit path length (cm⁻¹). Biological tissues are highly scattering due to variations in refractive index at cellular and subcellular levels [7] [1].

- Reduced Scattering Coefficient (μₛ′): In tissues, scattering is often anisotropic, with a preference for the forward direction. The reduced scattering coefficient, calculated as μₛ′ = μₛ(1 - g), accounts for this anisotropy and represents the equivalent isotropic scattering coefficient. Here, g is the anisotropy factor, which ranges from 0 for perfectly isotropic scattering to nearly 1 for highly forward-directed scattering [6] [1].

- Penetration Depth (δ): This is a critical parameter indicating the effective depth to which light can penetrate before being significantly attenuated. It is derived from the absorption and reduced scattering coefficients. When μₐ << 3μₛ′, it can be approximated as δ(λ) = 1 / √[3μₐ(λ)(μₐ(λ) + μₛ′(λ))] [6].

- Thermal Relaxation Time (TRT): This is the time required for tissue to dissipate about 50% of the thermal energy delivered by a laser pulse through conduction. Understanding TRT is essential for minimizing collateral thermal damage in laser-based surgeries and therapies [2].

The Role of Chromophores

Chromophores are molecules that absorb specific wavelengths of light. The primary chromophores in biological tissues and their absorption characteristics are:

- Hemoglobin: Found in blood, it absorbs strongly in the blue and green regions of the spectrum. Both oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin have an absorption peak around 806 nm, while oxygenated hemoglobin also has a significant absorption region around 900 nm [3].

- Melanin: Located in the skin, it absorbs strongly across the ultraviolet and visible spectrum, with absorption decreasing as wavelength increases [3].

- Water: The most abundant molecule in the body. It has relatively low absorption in the visible and NIR regions but shows strong absorption peaks in the infrared, particularly at wavelengths like 1940 nm, 2780 nm, and 2940 nm [3] [4].

- Lipids/Fat: Absorbs light in the NIR, with a dominant peak at 930 nm [3].

The inverse relationship between a photon's energy and its wavelength (λ = hc/E, where h is Planck's constant and c is the speed of light) means that shorter wavelengths possess higher energy but are more readily absorbed by chromophores, thus penetrating less deeply. Longer wavelengths in the NIR region have lower energy but encounter less absorption, allowing for deeper tissue penetration [3] [4].

Quantitative Data on Tissue Optical Properties

The optical properties of tissues vary significantly depending on tissue type, physiological state, and the wavelength of incident light. The following tables consolidate quantitative data from recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Absorption (μₐ) and Reduced Scattering (μₛ′) Coefficients of Human Upper Urinary Tract Tissues (400-700 nm range, measured via DIS and IMC) [6].

| Tissue Type | μₐ at 450 nm (cm⁻¹) | μₛ′ at 450 nm (cm⁻¹) | μₐ at 600 nm (cm⁻¹) | μₛ′ at 600 nm (cm⁻¹) | μₐ at 650 nm (cm⁻¹) | μₛ′ at 650 nm (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ureter | ~2.5 | ~25 | ~0.8 | ~18 | ~0.4 | ~16 |

| Fatty Tissue | ~0.7 | ~12 | ~0.3 | ~10 | ~0.2 | ~9 |

| Ureteral Carcinoma | ~4 | ~20 | ~1.2 | ~15 | ~0.6 | ~13 |

| Renal Pelvic Carcinoma | ~3.5 | ~22 | ~1 | ~16 | ~0.5 | ~14 |

Table 2: Absorption Coefficients (α) and Penetration Depth Rankings in Porcine Oral Gingival Tissue for Common Dental Laser Wavelengths [2].

| Laser Wavelength (nm) | Laser Type | Absorption Coefficient, α (cm⁻¹) | Ranking (Most to Least Absorbed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2940 | Er:YAG | 144.8 | 1 (Most Absorbed) |

| 2780 | Er,Cr:YSGG | ~120* | 2 |

| 450 | Blue Diode | 26.8 | 3 |

| 480 | Blue Diode | ~22* | 4 |

| 532 | KTP | ~18* | 5 |

| 1341 | Nd:YAP | ~15* | 6 |

| 632 | He-Ne | ~13* | 7 |

| 940 | Diode | ~11.5* | 8 |

| 980 | Diode | ~10.8* | 9 |

| 1064 | Nd:YAG | ~10.2* | 10 |

| 810 | Diode | 9.6 | 11 (Least Absorbed) |

Note: Values marked with an asterisk () are estimated from the ranking data provided in the source study [2].*

Table 3: Projected Light Penetration Depth (δ) in Human and Porcine Tissues [6].

| Tissue Type | δ at 450 nm (mm) | δ at 600 nm (mm) | δ at 650 nm (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Ureter | ~0.20 | ~0.45 | ~0.55 |

| Human Fatty Tissue | ~0.55 | ~0.90 | ~1.05 |

| Human Ureteral Carcinoma | ~0.18 | ~0.35 | ~0.45 |

| Human Renal Pelvic Carcinoma | ~0.19 | ~0.40 | ~0.50 |

| Porcine Ureter | ~0.20 | ~0.45 | ~0.45 |

| Porcine Fatty Tissue | ~0.50 | ~0.85 | ~1.00 |

Experimental Methods for Characterizing Optical Properties

Accurate measurement of tissue optical properties is fundamental for research and clinical protocol development. Several well-established experimental techniques are employed.

Double Integrating Sphere (DIS) System with Inverse Monte Carlo (IMC)

This method is considered a gold standard for measuring the optical properties of ex vivo tissue samples.

- Principle: A tissue sample is illuminated with a focused, collimated light beam. A double integrating sphere setup simultaneously measures the total transmittance (Tₜ) and diffuse reflectance (Rd) from the sample. These measured values are then used in an Inverse Monte Carlo (IMC) simulation to iteratively determine the absorption (μₐ) and reduced scattering (μₛ′) coefficients that would produce the measured Tₜ and Rd [6].

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Fresh tissue samples are collected and cut into specific geometries (e.g., 1 cm cubes). Sample thickness is precisely measured with a micrometer. Samples are sandwiched between glass slides and kept hydrated with saline to prevent dehydration and maintain optical properties [6].

- System Calibration: The DIS system is calibrated using diffuse reflectance standards and transmittance filters to ensure measurement accuracy [6].

- Measurement: The sample is placed at the input port of the DIS. Light from a broadband source (e.g., xenon lamp) is directed onto the sample. The spheres collect all transmitted and reflected light, which is then guided to a spectrometer for analysis [6].

- Inverse Monte Carlo Analysis: The measured Rd and Tₜ are input into an IMC model. The model varies μₐ and μₛ′ until the computed Rd and Tₜ match the experimental values within an acceptable error margin, thus yielding the final optical properties [6].

Kubelka-Munk (KM) Model

The KM model is a simpler, two-flux approximation method widely used to determine optical properties from reflectance and transmittance measurements.

- Principle: This model provides a mathematical framework to calculate the absorption (K) and scattering (S) coefficients based on the measured diffuse reflectance and transmittance of a tissue sample. Its major advantage is the direct analytical relationship between the coefficients and the measurements, avoiding complex computations [7].

- Protocol:

- Tissue samples are prepared similarly to the DIS method, with careful control of thickness.

- An integrating sphere coupled with a spectrometer is used to measure the total reflectance and transmittance of the tissue sample at specific laser wavelengths (e.g., 808, 830, 980 nm) [7].

- The Kubelka-Munk equations are applied to the measured data to derive the absorption and scattering coefficients. This model is particularly effective for optically thick samples where the light distribution is fully diffuse [7].

Time-Domain Diffuse Optics (TD-DO)

Time-domain techniques offer the highest information content for in-depth tissue characterization, particularly in living systems.

- Principle: The tissue is illuminated with an ultrashort picosecond laser pulse. A fast detector records the temporal distribution of the photons' time-of-flight (DTOF) as they are re-emitted from the tissue. Absorption affects the late-arriving photons (longer path lengths), while scattering influences the early part and the temporal broadening of the DTOF [1].

- Protocol:

- A pulsed laser source and time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) electronics are used.

- The source and detector are placed on the tissue surface (reflectance geometry) or on opposite sides (transmittance geometry).

- The measured DTOF is fitted with a solution to the photon diffusion equation to extract μₐ and μₛ′. This method allows for depth-resolved assessment of optical properties and is less affected by superficial tissue color [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in tissue optics requires specific tools and materials. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments.

Table 4: Essential Materials and Equipment for Tissue Optics Research.

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Double Integrating Sphere | Simultaneously measures total transmittance and diffuse reflectance from tissue samples, enabling accurate determination of optical properties [6]. | 4P-GPS-033-SL (Labsphere) [6] |

| Spectrometer | Detects and analyzes the spectrum of light transmitted through or reflected from tissue samples. | Maya2000Pro (Ocean Insight) [6] |

| Optical Parametric Oscillator (OPO) | A tunable laser system that generates specific wavelengths across a broad spectrum, allowing for wavelength-dependent studies. | VIS-OPO and MIR-OPO (Laserspec) [2] |

| Tissue Stabilization Setup | Holds tissue samples at a fixed thickness and prevents dehydration during measurements, ensuring consistent and reliable data. | Custom metal stabilization device with glass slides [2] |

| Calibrated Power Meter | Measures the absolute power of laser light before and after interaction with tissue, crucial for calculating attenuation. | Gentec-EO power meter [2] |

| Diffuse Reflectance Standards | Certified reference materials used to calibrate integrating sphere systems before tissue measurements. | SRS-99-010, SRS-10-010 (Labsphere) [6] |

| Fresh Ex Vivo Tissues | Biological samples from animal or human sources, used as models to study optical properties. | Porcine gingiva [2], human ureter and carcinomas [6], bovine adipose, chicken skin [7] |

Advanced Concepts and Research Applications

Photobiomodulation (PBM) and Dosimetry

Photobiomodulation therapy utilizes low-intensity light to stimulate biological processes. Its effectiveness is highly dependent on accurate dosimetry.

- Biphasic Dose Response: The therapeutic effect of PBM follows a biphasic pattern, often referred to as the Arndt-Schulz law. Very low doses may have no effect, moderate doses stimulate a positive therapeutic response, and excessively high doses can become inhibitory [5]. This makes precise dose delivery critical.

- Light Penetration and Dose: The penetration depth of PBM light in skin is the depth at which intensity falls to 37% (1/e) of its surface value [5]. Effective treatment of deep tissues requires wavelengths with sufficient penetration depth to deliver an adequate energy density to the target. Key parameters include wavelength, power density (irradiance, W/cm²), and energy density (fluence, J/cm²) [5].

Plasmonic Photothermal Therapy (PPTT)

PPTT is an advanced cancer treatment that combines the deep penetration of NIR light with the highly localized absorption of plasmonic nanoparticles.

- Principle: Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are introduced into tumor tissue. When irradiated with NIR light tuned to their localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) wavelength, the AuNPs efficiently absorb light and convert it into heat, selectively ablating the tumor [8].

- Optimization: The efficacy of PPTT depends on optimizing nanoparticle parameters (size, shape, composition) to match the LSPR to the tissue's optical window (700–1300 nm) and accounting for the thermal and optical properties of the specific target tissue [8]. Computational modeling, such as using Mie theory to calculate absorption cross-sections, is essential for protocol design [8].

Thermal therapy represents a cornerstone of modern medical treatment, leveraging controlled energy delivery to achieve precise biological effects. The fundamental principle underpinning all thermal therapies is selective photothermolysis, a theory described by Rox Anderson in 1983 that establishes the requirements for confining thermal damage to specific targets without affecting surrounding tissue [9]. This theoretical framework enables the entire spectrum of thermal interventions, from gentle hyperthermia to aggressive ablation, by providing the scientific basis for laser-tissue interactions [9].

The therapeutic landscape of thermal medicine spans a continuum defined by temperature ranges and their corresponding biological effects. Hyperthermia typically operates in the 39°C to 42°C range, focusing on physiological modulation and sensitization of tissue to other treatments [10]. In contrast, thermal ablation employs temperatures exceeding 44°C to achieve direct cellular destruction through protein denaturation and immediate necrosis [10]. The distinction between these modalities is not merely temperature-dependent but also defined by their mechanism of action, therapeutic objectives, and technical implementation.

Table 1: Fundamental Thermal Therapy Classifications

| Therapy Type | Temperature Range | Primary Mechanism | Therapeutic Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild Hyperthermia | 39°C - 42°C | Protein activation, membrane fluidity | Radiotherapy/chemotherapy sensitization |

| Moderate Hyperthermia | 42°C - 45°C | Heat shock protein induction, metabolic alteration | Immunological activation, drug delivery enhancement |

| Thermal Ablation | >44°C - 60°C | Protein denaturation, immediate coagulation | Direct tumor destruction |

| Irreversible Electroporation | Variable with significant Joule heating | Nanoscale membrane defects with thermal components | Non-thermal dominant cell death with thermal effects |

Hyperthermia: Mechanisms and Biological Effects

Molecular and Cellular Responses

Hyperthermia exerts its therapeutic effects through multifaceted biological mechanisms that operate at molecular, cellular, and tissue levels. At the molecular scale, heat shock proteins (HSPs) serve as critical mediators of the cellular stress response. These molecular chaperones, including HSP27, HSP47, HSP60/HSP10, HSP70, and HSP90, stabilize and repair damaged proteins, prevent harmful interactions between misfolded proteins, and facilitate the removal of defective cellular components [10]. The heat shock response represents a sequential information transmission process through the localized activity of these molecular chaperones [10].

The immunomodulatory effects of hyperthermia represent one of its most significant therapeutic mechanisms, particularly in oncology. Hyperthermia fundamentally alters the tumor microenvironment (TME) by promoting immunogenic cell death (ICD), enhancing the activity of immune cells including neutrophils, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells, and reducing immunosuppressive conditions [10]. This transformative capability allows hyperthermia to convert immunologically "cold" tumors with minimal immune infiltration into "hot" tumors characterized by significant immune cell presence and pro-inflammatory activity, thereby increasing their susceptibility to immune-mediated destruction [10].

Technical Implementation Modalities

Hyperthermia delivery systems encompass diverse technological approaches, each with specific tissue penetration characteristics and clinical applications. Magnetic hyperthermia therapy (MHT) utilizes magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) that generate localized heat when exposed to an alternating magnetic field (AMF), achieving deep tissue penetration through Néel and Brownian relaxation mechanisms [11]. This approach enables intracellular hyperthermia when combined with cell-targeting ligands, resulting in direct therapeutic heating of cancer cells [11].

Other hyperthermia technologies include radiofrequency energy-based ablation, microwave-based approaches, laser interstitial thermal therapy, nanoparticle-driven photothermal therapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation, and systemic whole-body hyperthermia (WBH) [10]. Each modality offers distinct advantages in terms of penetration depth, spatial precision, and temperature control, making them suitable for different clinical scenarios.

Table 2: Hyperthermia Delivery Technologies and Characteristics

| Technology | Energy Source | Penetration Depth | Temperature Control | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Hyperthermia (MHT) | Alternating magnetic field | Deep tissue (cm) | Moderate via nanoparticle concentration | Deep-seated tumors, combination therapies |

| Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) | Ultrasound waves | Several centimeters | High via real-time monitoring | Non-invasive ablation, targeted therapy |

| Laser Interstitial Therapy | Laser light | Limited (mm-cm) | High via fiber optic placement | Precise intracranial lesions, minimal access surgery |

| Radiofrequency Ablation | Radiofrequency current | Moderate (cm) | Moderate via impedance monitoring | Liver tumors, cardiac arrhythmias |

| Whole-Body Hyperthermia | External heating devices | Systemic | Challenging | Metastatic disease, immunomodulation |

| Photothermal Therapy | Light with nanoparticles | Shallow (mm) | Moderate | Superficial tumors, combination approaches |

Thermal Ablation: Mechanisms and Applications

Direct Thermal Destruction Mechanisms

Thermal ablation operates through direct energy delivery to achieve rapid and substantial tissue destruction. The primary mechanism involves protein denaturation that occurs when tissues are heated above 44°C, leading to immediate cellular necrosis and coagulation [10]. As temperatures increase further, more aggressive effects manifest, including carbonization at approximately 150°C-200°C and vaporization above 200°C, resulting in direct tissue removal [12]. The therapeutic objective of ablation is complete destruction of targeted tissue volumes while preserving surrounding healthy structures.

The clinical application of thermal ablation requires precise temperature monitoring to ensure efficacy while minimizing collateral damage. Fiber Bragg gratings (FBGs) have emerged as optimal sensing solutions for thermal monitoring during radiofrequency, laser, and microwave ablation procedures [12]. These sensors provide critical temperature feedback to control the ablation process, enabling investigation of different treatment parameters and quantification of factors such as proximity to blood vessels, perfusion effects, and tissue-specific responses [12].

Hybrid and Non-Thermal Ablation Modalities

The ablation landscape includes innovative approaches that combine thermal and non-thermal mechanisms. Irreversible electroporation (IRE) represents a particularly significant hybrid modality that primarily induces cell death through the formation of nanoscale defects in cellular membranes when exposed to brief, high-voltage electric pulses [13]. While the fundamental IRE mechanism occurs independently of thermally-induced processes, the application of therapeutic electric pulses inevitably results in secondary Joule heating of the tissue [13].

The distinction between IRE as a biophysical cellular response and IRE as a therapeutic ablation technique is crucial. When applied appropriately, it is possible to exploit the non-thermal cell death mechanism to destroy targeted tissue volumes without inducing clinically relevant thermal damage [13]. However, aggressive energy regimes in clinical pulse protocols can generate significant thermal effects that must be carefully managed through protocol design, utilization strategies, and specialized pulse delivery devices [13]. This nuanced understanding enables clinicians to maintain IRE as the predominant tissue death modality while minimizing therapy-limiting thermal damage to critical structures.

Experimental Methodologies and Research Protocols

In Vitro Hyperthermia and Ablation Assessment

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for evaluating thermal therapy efficacy and mechanisms. For magnetic hyperthermia assessment, researchers typically prepare cell cultures in standard media and suspend iron oxide nanoparticles (10-50 nm diameter) at concentrations ranging from 0.1-2 mg/mL [11]. Cells are incubated with nanoparticles for 4-24 hours to ensure cellular uptake, followed by exposure to an alternating magnetic field (100-400 kHz, 10-30 kA/m) for 30-60 minutes. During exposure, temperature monitoring via fiber optic sensors maintains the target hyperthermia range (41°C-45°C), and viability is assessed 24-48 hours post-treatment using MTT and apoptosis assays [11].

For laser ablation studies, the experimental workflow involves calibrating laser systems (typically diode or Nd:YAG lasers) to deliver specific fluences (20-100 J/cm²) at appropriate wavelengths for the target chromophore [9]. Tissue phantoms or cell cultures are positioned at standardized distances, and temperature monitoring using infrared cameras or embedded thermocouples records spatial and temporal thermal profiles. Researchers document specific treatment endpoints, including immediate color changes, swelling patterns, and the absence of adverse reactions such as blistering or cavitation, which represent danger signs [9]. Post-treatment analysis includes histological examination for coagulation necrosis dimensions and zone of apoptotic transition.

In Vivo Translation and Thermal Monitoring

Translational research protocols for thermal therapies require sophisticated monitoring and control systems. In preclinical models, researchers implant tumor xenografts subcutaneously in immunocompromised mice or utilize syngeneic models in immunocompetent animals [10]. For hyperthermia studies, animals receive localized heating via focused ultrasound or systemic warming in controlled environmental chambers, maintaining core temperatures of 39.5°C±0.5°C for 60 minutes [10]. Temperature verification occurs via rectal probes, and immune profiling follows at multiple timepoints through flow cytometry of blood, spleen, and tumor tissues.

Advanced thermal monitoring represents a critical component of ablation research. Multiplexed fiber Bragg grating (FBG) arrays provide distributed temperature sensing with high spatial resolution during radiofrequency, laser, and microwave ablation procedures [12]. These systems enable real-time thermal feedback for controlled energy delivery, allowing investigators to correlate thermal dose with resultant tissue effects and quantify the impact of physiological factors such as perfusion and proximity to vascular structures [12].

Research Reagents and Technical Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Thermal Therapy Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Iron oxide NPs (Fe₃O₄), Doped ferrites | Heat generation under alternating magnetic fields | Size (10-50 nm), coating (PEG, silica), functionalization (targeting ligands) |

| Photosensitizers | Copper sulfide NPs, Carbon dots, Organic dyes | Light absorption and thermal energy conversion | Extinction coefficient, photostability, biocompatibility |

| Temperature Sensors | Fiber Bragg gratings (FBGs), Infrared cameras | Real-time thermal monitoring during ablation | Spatial resolution, response time, multiplexing capability |

| Cell Viability Assays | MTT, Calcein-AM/propidium iodide, ATP assays | Quantification of treatment efficacy post-hyperthermia | Timing (24-72 hours), compatibility with nanoparticles |

| Immunological Reagents | Cytokine ELISA kits, Flow cytometry antibodies | Evaluation of immune modulation following hyperthermia | Panel design for innate/adaptive immune cells |

| Animal Models | Subcutaneous xenografts, Genetically engineered models | In vivo evaluation of thermal therapies | Tumor volume monitoring, thermal application challenges |

Visualization of Thermal Therapy Mechanisms

Thermal interaction mechanisms span a sophisticated continuum from physiological modulation in hyperthermia to direct destruction in ablation therapies. The fundamental understanding of laser-tissue interactions and selective photothermolysis provides the theoretical foundation for these interventions [9]. Current research gaps include insufficient studies on thermal therapies in diverse skin types, with most device safety data initially established on lighter skin tones before limited translation to darker skin [9]. Future directions should focus on optimizing combination approaches, such as magnetic hyperthermia with chemodynamic therapy [11] or hyperthermia with immunotherapy [10], while advancing thermal monitoring technologies to enhance precision and personalized treatment application across diverse patient populations.

Selective photothermolysis is a foundational concept in modern laser medicine that enables the precise targeting of specific structures within biological tissues. First articulated by Anderson and Parrish in 1983, this principle revolutionized dermatologic laser therapies by providing a scientific framework for selective thermal damage of microscopic targets with spatial precision previously unattainable [14] [15]. The core innovation lies in the selective absorption of pulsed radiation by specific chromophores, generating confined thermal damage to intended targets while preserving surrounding tissue. This paradigm forms the basis for numerous medical applications including vascular lesion treatment, hair removal, pigmented lesion correction, and various aesthetic procedures [14] [16]. Understanding selective photothermolysis is essential for researchers and clinicians working at the intersection of photobiology and therapeutic applications, as it provides the theoretical underpinnings for optimizing laser parameters to achieve predictable clinical outcomes across diverse tissue types.

Theoretical Foundations of Selective Photothermolysis

The Anderson-Parrish Principle

The theoretical framework of selective photothermolysis, as established by Anderson and Parrish, relies on three carefully optimized laser parameters that must be matched to the thermal and optical properties of the target tissue [14]. The mechanism operates through selective absorption of light by naturally occurring or artificially introduced chromophores, with subsequent conversion of light energy to thermal energy, resulting in localized thermal damage. The specificity of this interaction is governed by the relationship between laser pulse duration and the thermal relaxation time (TRT) of the target—the time required for the target to cool to half its peak temperature after energy absorption [14] [17]. When pulse duration is shorter than or equal to the TRT, thermal energy remains confined to the target structure, enabling precise photothermolysis. This principle has been extended to account for non-uniform absorption within targets, where heat diffusion from highly absorbing to weakly absorbing regions can achieve complete target destruction—a concept particularly relevant for hair follicle damage where melanin distribution is non-uniform [15].

Chromophores in Biological Tissues

The efficacy of selective photothermolysis depends fundamentally on the presence and concentration of light-absorbing molecules known as chromophores. The primary endogenous chromophores in human skin each exhibit distinct absorption spectra, determining their responsiveness to specific laser wavelengths [14] [16]:

- Melanin: Found in hair follicles, epidermis, and pigmented lesions, melanin demonstrates broad absorption across the ultraviolet to near-infrared spectrum (300-1200 nm), making it the primary target for hair removal and pigmented lesion treatment [15].

- Hemoglobin/Oxyhemoglobin: Present in blood vessels and vascular lesions, these chromophores exhibit strong absorption peaks in the 418, 542, and 577 nm ranges, enabling effective treatment of vascular conditions such as telangiectasias, port-wine stains, and hemangiomas [14] [16].

- Water: As a universal tissue component, water absorption increases significantly at wavelengths above 1100 nm, peaking at approximately 3000 nm, which facilitates ablative procedures using CO₂ (10,600 nm) and Er:YAG (2940 nm) lasers [14].

The presence of competing chromophores in the treatment area presents a significant consideration, particularly in darker skin types where epidermal melanin can absorb energy intended for deeper targets, increasing complication risks [16].

Table 1: Primary Endogenous Chromophores and Their Laser Applications

| Chromophore | Absorption Peaks | Primary Applications | Representative Lasers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanin | 300-1200 nm (broad) | Hair removal, pigmented lesions | Ruby (694 nm), Alexandrite (755 nm), Diode (810 nm), Nd:YAG (1064 nm) [15] |

| Hemoglobin/Oxyhemoglobin | 418, 542, 577 nm | Vascular lesions, vascular anomalies | Pulsed dye laser (585-595 nm), KTP (532 nm) [14] [16] |

| Water | >1100 nm (peak ~3000 nm) | Skin resurfacing, ablation | CO₂ (10,600 nm), Er:YAG (2940 nm) [14] |

Critical Laser Parameters

The Three Key Parameters

Successful selective photothermolysis requires precise optimization of three interdependent laser parameters, each playing a distinct role in achieving selective target damage [14]:

Wavelength: The laser wavelength must correspond to the absorption peak of the target chromophore while considering competing absorbers and depth of the target. Longer wavelengths generally penetrate deeper into tissue but may have lower absorption by the target chromophore. The optimal wavelength balances sufficient absorption by the target with adequate penetration depth and minimal competition from other chromophores [14] [16].

Pulse Duration: This critical parameter must be equal to or shorter than the thermal relaxation time (TRT) of the target to confine thermal damage. TRT is proportional to the square of the target size, meaning larger targets require longer pulse durations. For example, a small blood vessel (0.1 mm diameter) has a TRT of approximately 1-10 ms, while a hair follicle (0.3 mm diameter) has a TRT of approximately 10-100 ms [14] [15].

Fluence: The energy delivered per unit area (J/cm²) must be sufficient to raise the target temperature to a threshold that causes irreversible damage (typically above 60-70°C for protein denaturation) while avoiding excessive energy that could cause nonspecific tissue injury or insufficient energy that fails to destroy the target [14] [16].

Table 2: Laser Parameters for Common Clinical Applications

| Application | Target Chromophore | Typical Wavelength | Pulse Duration | Fluence Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hair Removal | Melanin (hair follicle) | 755 nm (Alexandrite), 810 nm (Diode), 1064 nm (Nd:YAG) [15] | 5-100 ms (adjusted to hair follicle size) [15] | 10-40 J/cm² [16] |

| Facial Telangiectasia | Hemoglobin | 532 nm (KTP), 585-595 nm (PDL) [14] | 1-50 ms (adjusted to vessel diameter) [14] | 6-10 J/cm² (varies by device) |

| Pigmented Lesions | Melanin | 532 nm (Q-switched), 755 nm (Alexandrite) [14] | 10-100 nanoseconds (Q-switched) [14] | 2-8 J/cm² (varies by device) |

| Skin Resurfacing | Water | 10,600 nm (CO₂), 2940 nm (Er:YAG) [14] | 0.1-1 ms (ablative) | Varies significantly |

Thermal Relaxation Time and Tissue Effects

The thermal relaxation time (TRT) represents a fundamental concept in selective photothermolysis, defining the time required for a heated target to dissipate approximately 63% of its thermal energy to the surrounding tissue through conduction [17]. This parameter is mathematically related to the square of the target size, making larger targets require significantly longer cooling times. The relationship between pulse duration and TRT directly determines the spatial confinement of thermal damage—when pulse duration exceeds TRT, heat diffusion causes collateral injury to surrounding tissues [14] [17].

Laser-induced thermal effects follow a predictable temperature-dependent progression, with distinct biological responses occurring at specific temperature thresholds [17]:

- 40-50°C: Hyperthermia range characterized by reversible molecular bond disruption, enzyme activity reduction, and membrane alterations.

- 60-80°C: Protein denaturation, collagen coagulation, and irreversible cell necrosis occur—the primary target range for most selective photothermolysis procedures.

- 100°C: Water vaporization with bubble formation and thermal decomposition of tissue fragments.

- >100°C: Carbonization with release of carbon atoms and tissue blackening.

- >300°C: Tissue melting with complete architectural destruction.

Table 3: Temperature-Dependent Tissue Effects in Laser-Tissue Interactions

| Temperature Range | Biological Effect | Clinical Significance | Reversibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40-50°C | Hyperthermia: enzyme activity reduction, cell membrane alteration | Target for hyperthermia-based therapies | Reversible |

| 60-80°C | Protein denaturation, coagulation, necrosis | Primary target for most photothermolysis procedures | Irreversible |

| 100°C | Vaporization, thermal decomposition (ablation) | Tissue ablation, skin resurfacing | Irreversible |

| >100°C | Carbonization | Generally undesirable side effect | Irreversible |

| >300°C | Melting | Generally undesirable side effect | Irreversible |

Experimental Methodology and Research Protocols

Standardized Experimental Framework

Research in selective photothermolysis requires meticulous experimental design to isolate and evaluate individual parameters. A standardized protocol for investigating laser-tissue interactions should incorporate the following methodological considerations:

Target Selection and Characterization: Prior to laser exposure, targets (e.g., hair follicles, blood vessels, artificial chromophores) must be precisely characterized regarding size, depth, chromophore concentration, and surrounding tissue properties. Histological analysis, spectrophotometry, and high-resolution imaging provide essential baseline data [14] [15].

Parameter Optimization Matrix: Systematic investigation should employ a factorial design varying wavelength, pulse duration, and fluence across predetermined ranges. Each parameter combination requires sufficient replicates to establish statistical significance, with appropriate controls for tissue variability [14] [17].

Thermal Monitoring: Real-time temperature monitoring during laser exposure is essential using infrared thermography, thermocouples, or fluorescent thermal probes. This enables correlation of laser parameters with actual tissue temperature profiles and verification of theoretical models [17].

Outcome Assessment: Post-treatment evaluation should include immediate assessment (erythema, edema), short-term effects (coagulation, necrosis), and long-term outcomes (tissue regeneration, scarring). Histological analysis with standard staining (H&E, Masson's trichrome) provides microscopic evidence of selective damage [15].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Selective Photothermolysis Investigations

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Ex Vivo Tissue Models | Simulating human skin response | Provides controlled environment for parameter optimization without patient risk [17] |

| Artificial Chromophores | Standardized light absorbers | Enables controlled studies of absorption parameters without biological variability [14] |

| Thermographic Cameras | Non-contact temperature mapping | Quantifies spatial and temporal temperature distribution during laser exposure [17] |

| Histology Stains (H&E, Trichrome) | Tissue structure visualization | Demonstrates microscopic selective damage and collateral tissue effects [15] |

| Optical Phantoms | Simulating tissue optical properties | Provides standardized medium for light distribution studies [17] |

| Cell Viability Assays | Assessing cellular response to thermal injury | Quantifies threshold for irreversible cellular damage [17] |

Research Workflow and Decision Framework

The following diagram illustrates the systematic decision process for designing selective photothermolysis experiments and applications:

This workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of parameter optimization in selective photothermolysis research, where histological feedback informs subsequent parameter adjustments to achieve maximal selectivity.

Advanced Considerations and Research Directions

Extended Theory and Computational Modeling

The extended theory of selective photothermolysis addresses scenarios where chromophore distribution within targets is non-uniform, as occurs in hair follicles where melanin is concentrated in specific regions rather than distributed evenly [15]. In such cases, weakly absorbing areas may be destroyed through heat diffusion from highly absorbing regions, requiring adjustments to standard parameters. Computational modeling using Monte Carlo simulations for light transport and finite element analysis for heat distribution provides powerful tools for predicting these complex interactions [18] [17]. The Arrhenius formalism enables quantification of thermal damage kinetics through the relationship: Ω(𝑡) = 𝐴∫exp(−𝐸/𝑅𝑇(𝑡'))𝑑𝑡', where A is the frequency factor, E is the activation energy, R is the universal gas constant, and T(t') is temperature history [17]. This mathematical approach allows researchers to predict cell viability following laser exposure and optimize protocols for specific tissue effects.

Emerging Applications and Technological Innovations

Recent advances in selective photothermolysis research have expanded beyond traditional dermatologic applications. In ophthalmology, IPL technology has been adapted for managing meibomian gland dysfunction in dry eye disease [16]. Novel approaches combining selective photothermolysis with photodynamic therapy enhance precision in oncologic applications. Fractional laser technology represents another evolution of the principle, creating microscopic treatment zones of thermal injury surrounded by unaffected tissue to accelerate healing [18]. Research continues into new chromophore targets, including exogenous absorbers such as gold nanoparticles and indocyanine green for deeper tissue applications. The integration of real-time thermal imaging with closed-loop parameter adjustment systems represents the next frontier in smart laser therapies that automatically adapt to individual tissue responses [17].

Within the fundamental research of laser-tissue interactions, understanding the thermal effects on biological tissues is paramount. The specific tissue effect is predominantly a function of the peak temperature achieved and the duration of exposure. This guide provides a detailed examination of the three primary temperature-dependent effects: coagulation, vaporization, and carbonization, which are critical for applications ranging from surgical oncology to drug delivery system development.

The following table summarizes the key parameters and characteristics associated with each thermal effect.

Table 1: Temperature-Dependent Tissue Effects and Parameters

| Thermal Effect | Temperature Range (°C) | Primary Mechanism | Macroscopic Appearance | Key Biomolecular Alterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coagulation | 60 - 90 | Protein Denaturation & Enzyme Inactivation | Opaque, blanched white | Hemoglobin precipitation, collagen hyalinization, loss of enzymatic activity. |

| Vaporization | ≥ 100 | Liquid-to-Gas Phase Transition of Cellular Water | Tissue ablation, plume generation | Cellular architecture destroyed; immediate volumetric removal. |

| Carbonization | ≥ 150 - 200 | Dehydration & Pyrolysis of Organic Matrices | Blackened, charred eschar | Molecular breakdown into elemental carbon and volatile gases. |

Detailed Mechanisms and Experimental Analysis

Coagulation

Coagulation is a non-ablative process resulting from the denaturation of proteins and nucleic acids. The structural integrity of cells is compromised without immediate tissue removal.

- Experimental Protocol for In Vitro Coagulation Threshold Analysis:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare thin sections (e.g., 1 mm) of ex vivo liver or muscle tissue and place them in a temperature-controlled saline bath.

- Thermal Exposure: Using a heated probe or low-power laser (e.g., Nd:YAG at 1064 nm), expose tissue samples to a fixed temperature (e.g., 50, 60, 70, 80, 90°C) for a standardized duration (e.g., 10 seconds).

- Histological Analysis: Fix samples in formalin, embed in paraffin, section, and stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). Analyze under a microscope for signs of coagulation: loss of cellular detail, eosinophilic (pink) cytoplasm, and pyknotic nuclei.

- Viability Staining: Alternatively, use a fluorescent live/dead assay (e.g., Calcein-AM/Ethidium homodimer-1) on cell cultures exposed to the same thermal conditions. Quantify the percentage of non-viable (coagulated) cells via flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

Vaporization

Vaporization is an ablative process where tissue is removed through the rapid conversion of intracellular and extracellular water into steam. This process requires the latent heat of vaporization and results in precise cutting or ablation.

- Experimental Protocol for Vaporization Efficiency Measurement:

- Setup: Use a high-power, strongly absorbed laser (e.g., CO₂ laser at 10.6 µm or Er:YAG at 2.94 µm) directed at a tissue phantom (e.g., hydrated gelatin) or ex vivo tissue.

- Ablation: Fire the laser in a pulsed mode with controlled energy fluence (J/cm²) and pulse duration.

- Measurement: Measure the volume of the resulting ablation crater using optical coherence tomography (OCT) or confocal microscopy. Alternatively, weigh the sample before and after ablation to determine mass loss.

- Data Analysis: Plot the ablation depth or mass loss against the applied energy fluence. The slope of the linear region represents the ablation efficiency (µm/J or mg/J).

Carbonization

Carbonization occurs at extreme temperatures under conditions of limited oxygen, leading to the pyrolysis of proteins and carbohydrates into elemental carbon and smoke.

- Experimental Protocol for Carbonization Onset Determination:

- Setup: Employ a continuous-wave laser (e.g., diode laser) with a small spot size focused on a dry tissue sample (e.g., desiccated skin or pure collagen sheet) to minimize vaporization.

- Exposure: Apply increasing power densities until visible blackening is observed.

- Spectroscopic Analysis: Use a Raman spectrometer to analyze the treated spot. The appearance of characteristic G and D bands (~1580 cm⁻¹ and ~1350 cm⁻¹) confirms the formation of disordered carbon structures, signifying carbonization.

- Thermal Imaging: Simultaneously, use an infrared thermal camera to correlate the visible onset of carbonization with the surface temperature of the tissue.

Visualizing Thermal Effect Pathways and Workflows

Thermal Effects Pathway

Thermal Effect Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Thermal Effect Studies

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Ex Vivo Tissue Models (Porcine/ bovine liver, skin) | Standardized, reproducible substrate for initial laser-tissue interaction studies and protocol development. |

| 3D Cell Culture Spheroids | More physiologically relevant in vitro model for studying thermal effects on tumor microenvironments. |

| H&E Staining Kit | Standard histological stain for visualizing general tissue architecture and coagulative necrosis post-exposure. |

| Calcein-AM / EthD-1 Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit | Fluorescent assay for quantitatively distinguishing live (green) from dead/coagulated (red) cells. |

| Formalin Solution (10% Neutral Buffered) | Tissue fixative for preserving tissue morphology after thermal treatment for histological analysis. |

| Hydrated Gelatin Phantoms | Tissue-simulating material with tunable optical properties for controlled ablation (vaporization) studies. |

| Raman Spectrometer System | For non-destructive, label-free chemical analysis to definitively identify carbonization via characteristic spectral bands. |

| Infrared Thermal Camera | To measure surface temperature in real-time during thermal exposure, correlating visual effects with temperature. |

The interaction of laser light with biological tissues and synthetic agents generates two primary mechanical phenomena: photoacoustic effects and vapor bubble dynamics. These interconnected processes form a critical foundation for advanced biomedical applications, including therapeutic drug delivery, precise tissue ablation, and cutting-edge medical imaging techniques. The photoacoustic effect describes the conversion of absorbed light energy into acoustic waves through rapid thermoelastic expansion [19]. When short-pulsed laser light illuminates an absorbing material, the absorbed energy causes localized heating and subsequent thermoelastic expansion, generating broadband acoustic waves that can be detected using conventional ultrasound transducers [20]. This light-in-sound-out principle enables photoacoustic imaging (PAI) to combine the rich contrast of optical absorption with the deep penetration and high resolution of ultrasound imaging [19].

Vapor bubble dynamics encompasses the formation, expansion, and collapse of gaseous cavities within liquids, driven by laser energy deposition. These dynamics occur when laser intensity exceeds specific thresholds, causing rapid phase transitions in the absorbing medium or in specialized phase-change contrast agents [21] [22]. The resulting bubbles undergo complex evolution governed by inertial forces, surface tension, and surrounding pressure fields, generating powerful mechanical effects including shockwaves and high-velocity micro-jets that can be harnessed for therapeutic purposes [23] [24]. Understanding the fundamental physics governing these mechanical interactions is essential for optimizing their application in biomedical research and clinical practice.

Laser-Tissue Interaction Mechanisms

Laser light interacts with biological tissues through several primary mechanisms, with the specific outcome determined by laser parameters (wavelength, pulse duration, fluence) and tissue properties (absorption, scattering). The four fundamental light-tissue interactions are transmission, reflection, scattering, and absorption [25]. For mechanical bioeffects, absorption is the most critical interaction, as it initiates the energy conversion processes that generate both photoacoustic signals and vapor bubbles.

Photothermal interactions occur when laser energy is converted to heat, raising tissue temperature. The biological response depends on the magnitude and duration of temperature increase: enzymatic deactivation occurs at 40–45°C, protein denaturation at 60°C, and vaporization at 100°C [25]. When laser energy is delivered in pulses shorter than the thermal relaxation time of the target tissue, selective photothermolysis can be achieved, allowing precise targeting of specific chromophores with minimal collateral damage [25].

Photoacoustic interactions represent a specialized form of photothermal interaction where confined, rapid heating generates acoustic waves rather than bulk thermal damage. This occurs when short laser pulses (typically nanoseconds) are absorbed, creating rapid thermoelastic expansion that produces detectable ultrasound waves [20]. The initial pressure (P) of the generated photoacoustic wave is governed by the equation: P = Γ·T · σ · μa · F, where Γ is the Grüneisen parameter (dimensionless), σ is the heat conversion efficiency, μa is the optical absorption coefficient, and F is the optical fluence [20].

Cavitation interactions involve the formation of vapor bubbles when laser energy is absorbed by water or other volatile components, causing rapid vaporization. For infrared lasers such as Ho:YAG (λ = 2.08 μm) and Er:YAG (λ = 2.94 μm) that are strongly absorbed by water, this occurs through direct absorption by the tissue water content [23]. The resulting bubbles undergo complex expansion and collapse cycles, generating substantial mechanical forces that can be harnessed for tissue ablation or disrupted to minimize collateral damage [23].

Quantitative Parameters and Threshold Data

The mechanical effects of laser-tissue interactions are governed by precise physical parameters that determine the efficacy and safety of biomedical applications. The tables below summarize key quantitative relationships and threshold values essential for experimental design.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Photoacoustic Effect and Bubble Dynamics

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Typical Range/Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grüneisen Parameter | Γ | Dimensionless parameter describing thermoelastic conversion efficiency | Tissue-dependent (0.1-0.5) |

| Optical Absorption Coefficient | μₐ | Measure of how strongly a medium absorbs light at specific wavelength | Varies by tissue and wavelength (0.1-1000 cm⁻¹) |

| Optical Fluence | F | Optical energy delivered per unit area | Limited by MPE (Maximum Permissible Exposure) |

| Heat Conversion Efficiency | σ | Fraction of absorbed energy converted to heat | σ = 1 - φ (where φ is fluorescence quantum yield) |

| Normalized Distance | γ | Ratio of distance from bubble center to boundary over maximum bubble radius (h/Rmax) | γ < 2 for material removal; optimal at 0.1-0.7 [23] |

| Micro-jet Velocity | vⱼₑₜ | Velocity of collapsing bubble micro-jet | 40-150 m/s (dependent on γ) [23] |

| Hydrodynamic Impact Pressure | Pᵢₘₚₐcₜ | Pressure generated by micro-jet impingement | 5-210 MPa [23] |

Table 2: Laser and Material Properties for Bubble Dynamics

| Factor | Impact on Bubble Dynamics | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Pulse Duration | Short pulses (<1 μs) produce regular circular bubbles; long pulses (>100 μs) create elongated, irregular bubbles [24] | Pulse duration determines bubble shape and oscillation characteristics |

| Normalized Distance (γ) | Determines bubble collapse symmetry and micro-jet direction; γ = h/Rmax where h is distance to boundary and Rmax is maximum bubble radius [23] | Optimal tissue ablation observed at γ ≤ 0.7; micro-jet velocity and impact pressure strongly γ-dependent |

| Surface Roughness | Critical in distant-field cleaning effects; textured surfaces enable localized cavitation and enhance bacterial disruption [26] | Smooth surfaces suppress fluid dynamics in constrained geometries |

| Perfluorocarbon Boiling Point | Lower boiling point PFCs (C₃F₈: -36.7°C; C₄F₁₀: -1.96°C; C₅F₁₂: 29.24°C) enable vaporization at lower laser fluence [22] | PFC selection allows tuning of optical droplet vaporization threshold |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

High-Speed Imaging of Cavitation Bubble Dynamics

The experimental setup for investigating laser-induced cavitation bubbles typically includes a pulsed laser system, a high-speed imaging camera, and a transparent containment vessel. For Ho:YAG laser ablation studies (λ = 2.08 μm, pulse width = 300 μs, pulse energy = 2 J), bone specimens are affixed in a quartz tank filled with liquid medium, and the optical fiber is positioned perpendicular to the tissue surface with a specific stand-off distance [23]. The high-speed camera (e.g., Photron SA6) captures bubble dynamics at frame rates up to 75 kHz with exposure times as short as 13 μs, synchronized with laser firing [24]. Temporal analysis focuses on identifying key stages: initial bubble formation (Frame A), growth stage (Frames B-D), collapse initiation (Frame E), micro-jet development (Frames F-G), and final implosion (Frame H) [23]. Quantitative measurements include bubble radius versus time, micro-jet velocity, and collapse timing, with particular attention to the normalized distance γ = h/Rmax, which significantly influences bubble behavior and tissue effects [23].

Optical Droplet Vaporization Threshold Measurements

The protocol for determining optical droplet vaporization (ODV) thresholds utilizes gold nanoparticle-templated perfluorocarbon (PFC) droplets with varying core materials [22]. Microbubbles are fabricated using lipid shells (DAPC, DSPE-PEG2K, DSPE-PEG2K-B) and different PFC gas cores (C₃F₈, C₄F₁₀, C₅F₁₂) through sonication or amalgamation methods, followed by condensation into droplets through cooling and pressurization (~50 psi) [22]. The droplet suspension is placed in an optical cuvette and exposed to pulsed laser light at varying fluence levels (typically in the near-infrared range). Vaporization is detected visually by the appearance of bubbles or acoustically using a hydrophone. The threshold fluence is recorded as the minimum laser energy required to consistently vaporize droplets, with studies demonstrating that lower boiling point PFCs (C₃F₈ < C₄F₁₀ < C₅F₁₂) require lower vaporization fluences [22]. Size distribution analysis via dynamic light scattering confirms droplet stability and monodispersity before experimentation.

Photoacoustic Signal Characterization

Photoacoustic signal generation and detection protocols involve preparing tissue-mimicking phantoms with embedded optical absorbers or contrast agents [20] [19]. The experimental setup includes a tunable pulsed laser system (typically Nd:YAG with OPO or titanium-sapphire), ultrasound transducers with appropriate center frequencies (1-50 MHz depending on resolution requirements), and data acquisition hardware. For quantitative PA measurements, the locally available fluence (F) must be calibrated using a power meter, and the absorption coefficient (μₐ) of the target chromophore should be verified spectrophotometrically. The generated PA signals are averaged multiple times to improve signal-to-noise ratio, and spectral unmixing techniques are applied when multiple contrast agents are present [20]. Critical parameters to record include laser wavelength, pulse duration, pulse repetition rate, transducer characteristics, and sample temperature.

Figure 1: Photoacoustic Signal Generation Workflow

Advanced Dynamics and Specialized Phenomena

Non-Spherical Bubble Collapse and Micro-Jet Formation

When cavitation bubbles form near boundaries (tissue surfaces, surgical tools), they collapse asymmetrically, generating high-velocity micro-jets directed toward the adjacent surface. This non-spherical collapse occurs when the normalized distance γ = h/Rmax is less than approximately 2, with the most significant effects observed at γ ≤ 0.7 [23]. High-speed imaging studies reveal that micro-jet velocity increases as γ decreases, reaching values of 40-150 m/s depending on the specific geometry and laser parameters [23]. The resulting hydrodynamic impact pressure can reach 210 MPa, substantially exceeding the yield strength of most biological tissues and enabling mechanical tissue removal [23]. This phenomenon explains the enhanced ablation efficiency observed in liquid-assisted laser surgery, where the confined liquid layer facilitates mechanical tissue removal through micro-jet impingement and toroidal vortex run-off effects [23].

Cascaded Cavitation with Pulse Trains

A novel regime of laser cavitation emerges when using trains of microsecond laser pulses with inter-pulse periods shorter than the bubble lifetime. In this cascaded cavitation, subsequent laser pulses in the train pass through the gas phase of the initial bubble and evaporate additional liquid at the gas-liquid interface [24]. This produces elongated, complex-shaped bubbles with significantly larger volumes (4.6 mm length for 7-pulse train versus 3.8 mm for single pulse in experimental conditions) [24]. The practical implication is enhanced energy deposition and potentially more efficient tissue ablation or fragmentation, particularly relevant for lithotripsy and other surgical applications where extended bubble dimensions could improve therapeutic outcomes.

Optical Droplet Vaporization for Contrast Enhancement

Liquid perfluorocarbon droplets incorporating optical absorbers can be vaporized through photothermal heating using pulsed lasers, a process termed optical droplet vaporization (ODV) [22]. These phase-change agents serve as dual-mode contrast agents, providing initial photoacoustic contrast through their absorbing components and generating enhanced ultrasound contrast after vaporization into gas-filled microbubbles [22] [27]. The ODV threshold depends critically on the PFC core material, with lower boiling point PFCs (C₃F₈ < C₄F₁₀ < C₅F₁₂) vaporizing at lower laser fluences [22]. This tunability enables the design of droplet populations with specific activation thresholds, potentially allowing for spatially selective activation in complex biological environments.

Figure 2: Cascaded Cavitation with Laser Pulse Trains

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Perfluorocarbon Droplets | Phase-change contrast agents for ODV; can be vaporized by laser or ultrasound [21] [22] | Core options: C₃F₈ (bp -36.7°C), C₄F₁₀ (bp -1.96°C), C₅F₁₂ (bp 29.24°C); size: submicron to several microns [22] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Light absorbers for enhancing ODV efficiency; can be incorporated in droplet shells or attached to surfaces [22] | Typical sizes: 5-50 nm; surface functionalization with avidin-biotin chemistry for specific binding [22] |

| Lipid Shell Components | Stabilizing shells for microbubbles and droplets; provide biocompatibility and functionalization sites [22] | Common lipids: DAPC, DSPE-PEG2K, DSPE-PEG2K-B; molar ratios typically 90:9:1 [22] |

| Copper Sulfate Solution | Tissue-simulating phantom material with controlled absorption properties [24] | μₐ ≈ 10.7 cm⁻¹ at 1000 nm; mimics liver (4 cm⁻¹) and brain (5 cm⁻¹) absorption [24] |

| High-Speed Camera Systems | Visualization of bubble dynamics with microsecond temporal resolution [23] [24] | Frame rates: 75 kHz; exposure time: 13 μs; resolution: 1024×1024 pixels [24] |

| PVDF Hydrophones | Acoustic detection of shock waves and bubble oscillations [24] | Bandwidth: 100 kHz-100 MHz; sensitivity: 0.48 μV/Pa [24] |

Applications in Biomedical Research and Therapeutics

The controlled application of photoacoustic effects and vapor bubble dynamics enables numerous advanced biomedical applications with both diagnostic and therapeutic functions. In photoacoustic imaging, exogenous contrast agents including methylene blue, indocyanine green, and gold nanoparticles provide enhanced contrast for visualizing optically transparent structures like lymphatic vessels and tumors [20]. The combination of optical absorption contrast with ultrasound detection depth enables functional imaging of physiological parameters including blood oxygen saturation, total hemoglobin concentration, and biomarker distribution [19].

In therapeutic applications, laser-induced cavitation bubbles facilitate precise mechanical tissue ablation with minimal thermal damage. The hydrodynamic effects of bubble collapse—particularly micro-jet impingement—enable efficient hard tissue ablation in orthopedic and dental procedures when properly calibrated for normalized distance (γ) [23]. In soft tissues, the mechanical effects of bubble dynamics can enhance drug delivery by increasing cell membrane permeability or disrupting vascular barriers [21] [24].

Phase-change droplet agents provide unique capabilities for both imaging and therapy. These droplets can be activated in specific locations through optical or acoustic triggering, generating microbubbles that provide enhanced ultrasound contrast or therapeutic effects through localized mechanical action [22] [27]. This activation can be spatially and temporally controlled, enabling targeted interventions with reduced systemic effects. Recent applications have expanded to include tissue regeneration, where precisely controlled cavitation dynamics may stimulate beneficial biological responses [21].

Mechanical interactions involving photoacoustic effects and vapor bubble dynamics represent a sophisticated domain of laser-tissue interactions with broad applicability in biomedical research and clinical practice. The fundamental physics governing these phenomena—including the photoacoustic wave generation equation, bubble dynamics equations, and phase transition thermodynamics—provide a theoretical foundation for designing targeted interventions. Experimental methodologies employing high-speed imaging, acoustic detection, and specialized contrast agents enable detailed investigation of these complex processes. As research continues to advance understanding of these mechanical interactions, particularly through the development of tunable phase-change agents and optimized laser parameters, applications in precise tissue ablation, controlled drug delivery, and multimodal imaging will continue to expand, offering new opportunities for scientific discovery and clinical innovation.

Advanced Computational Modeling and Clinical Translation of Laser Therapies

The study of laser-tissue interactions is a cornerstone of modern biophotonics and therapeutic medical device development. Accurate predictive models are essential for optimizing treatment efficacy and ensuring patient safety, as they provide insights into complex, coupled physical phenomena that are difficult to measure experimentally. At the heart of these models lie two critical computational frameworks: bioheat equations, which govern the transfer of thermal energy within biological systems, and thermal fluid-structure interaction (Thermal-FSI) models, which describe the coupled mechanical and fluid-dynamic response of tissue to thermal loads [28] [29]. These frameworks enable researchers and drug development professionals to simulate and understand the fundamental processes occurring during laser-based therapies, such as the temperature-driven ablation of dermatological lesions or the thermal coagulation of blood vessels. The evolution from classical analytical models to sophisticated, multiphysics numerical simulations represents a significant advancement in the field, allowing for patient-specific treatment planning and the development of novel laser applications [30].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core frameworks. It details the underlying principles, mathematical formulations, and implementation methodologies that are vital for constructing robust computational models of laser-tissue interactions. By integrating these frameworks, researchers can move beyond simplistic temperature predictions to a more holistic view that includes stress development, tissue deformation, and phase changes, thereby capturing the true multiphysics nature of the interaction.

Bioheat Transfer Models: From Classical to Advanced Formulations

Bioheat transfer models simulate how thermal energy propagates and is distributed within living tissues. This is crucial for predicting the extent of thermal damage during laser procedures.

The Foundation: Pennes Bioheat Equation

Introduced in 1948, the Pennes bioheat equation remains the most widely used model for simulating heat transfer in biological tissue [30]. It formulates the energy balance by accounting for key physiological heat sources and sinks. Its general form is expressed as:

[ \rho c \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = k \Delta T + \rhob cb \omegab (Tb - T) + E ]

where (E = Qr + Qm) represents the combined external laser heating ((Qr)) and metabolic heat generation ((Qm)) [30]. The model's robustness stems from its incorporation of several phenomenological mechanisms:

- Thermal conduction ((k \Delta T)): Heat diffusion through the tissue.

- Blood perfusion ((\rhob cb \omegab (Tb - T))): Heat exchange between flowing blood and the surrounding tissue.

- Metabolic heat generation ((Q_m)): Heat produced by cellular metabolism.

- Spatial heating ((Q_r)): Energy deposited by an external source, such as a laser.

Despite its widespread use, the classical Pennes model is derived from Fourier's law, which assumes infinite speed of heat propagation, a limitation that becomes significant in applications involving very short laser pulses or extremely localized heating [30].

Advanced Non-Fourier Formulations

To address the limitations of the classical model, advanced formulations incorporate a thermal relaxation time ((\tau_q)), which represents the finite time required for a heat flux to establish following a temperature gradient. This leads to a more physically realistic model of heat transfer, especially under rapid heating conditions [31] [30].

The Cattaneo-Vernotte model modifies the classical Fourier law, resulting in a hyperbolic partial differential equation that supports thermal wave propagation at a finite speed [30]. This non-Fourier framework is critical for modeling laser-tissue interactions with high spatial and temporal precision.

Further refinements include the fractional-order bioheat model, which captures memory-dependent and non-local heat transport phenomena. Experimental validations using ex-vivo tissue samples (e.g., kidney, heart, liver) have demonstrated that fractional models predict temperature trajectories with lower mean absolute error (MAE) and root-mean-square error (RMSE) compared to classical models [31]. Another advanced approach integrates the telegraph equation into the bioheat model, providing a robust framework for simulating localized point heating of diseased tissue, effectively represented using Dirac delta functions [30].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Bioheat Transfer Models

| Model | Governing Principle | Key Parameter | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Pennes [30] | Fourier's Law | Blood Perfusion Rate ((\omega_b)) | Simple, computationally efficient | Infinite heat propagation speed |

| Cattaneo-Vernotte (Non-Fourier) [30] | Hyperbolic Heat Wave | Thermal Relaxation Time ((\tau_q)) | Finite heat speed, accurate for short pulses | More complex numerical implementation |

| Fractional-Order [31] | Fractional Calculus | Fractional Order ((\alpha)) | Captures memory effects, high accuracy | Computationally intensive, parameter sensitivity |

| Telegraph Equation [30] | Damped Wave Equation | Relaxation Time Parameter | Models wave-like and diffusive behavior | Complex analytical solutions |

Thermal Fluid-Structure Interaction (Thermal-FSI) Models

While bioheat models predict temperature fields, Thermal-FSI models describe the complex, coupled thermomechanical response of tissue, including deformation, fluid expansion, and stress generation. This is vital for predicting mechanical outcomes like scarring or tissue rupture.

Core Components of a Thermal-FSI Framework

A comprehensive Thermal-FSI framework for laser-tissue interaction integrates several physical domains [28]:

- Optical Energy Deposition: Laser light transport in tissue is typically modeled using the diffusion approximation of the radiative transport equation, accounting for scattering and absorption.

- Bioheat Transfer: The deposited energy serves as a source term in a bioheat equation (e.g., Pennes or a non-Fourier variant) to calculate the transient temperature field.

- Phase Change and Fluid Dynamics: The model accounts for fluid expansion and water vaporization within the tissue, leading to pressure buildup.

- Nonlinear Tissue Mechanics: The temperature and pressure fields act as loads on the tissue structure, which is modeled using hyperelastic material laws to predict deformation and stress.

The Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) Formulation

A critical numerical technique for implementing Thermal-FSI is the Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) formulation [28]. This method combines the strengths of Lagrangian and Eulerian descriptions, making it ideally suited for problems involving large deformations and moving boundaries, such as those induced by laser ablation. The ALE framework allows for the independent movement of the computational mesh, enabling accurate tracking of the deforming tissue structure (a Lagrangian strength) while efficiently handling fluid flow and phase changes (an Eulerian strength). This capability is indispensable for simulating the coupled thermal, mechanical, and fluidic effects during laser therapy [28].

Constitutive Modeling of Tissue

Biological tissues exhibit nonlinear, hyperelastic mechanical behavior. Early FSI models often assumed isotropic, linear elasticity, but more accurate approaches require advanced constitutive models. For skin and other soft tissues, the Ogden and Yeoh models for hyperelasticity are frequently employed [28]. These models can capture the large-strain, stress-strain responses of compressible rubber-like solids, providing a more realistic representation of tissue deformation under thermal stress than linear models.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Validating computational models requires rigorous experimental protocols. The following methodologies are commonly employed in the field.

Protocol 1: Validating Fractional-Order Bioheat Models

This protocol outlines the steps for experimentally validating a fractional-order bioheat model against ex-vivo data [31].

- Tissue Sample Preparation: Obtain 30 ex-vivo tissue samples (e.g., liver, kidney, heart). Maintain samples at room temperature (20–25 °C).

- Thermophysical Property Measurement: Characterize each sample by measuring its thermal diffusivity (D), conductivity (k), and volumetric specific heat capacity (Ch). Reported values are approximately (\rho \approx 1050\ kg/m^3), (D \approx 0.15\ mm^2/s), and (k \approx 0.5\ W/m\°C) [31].

- Controlled Laser Heating: Perform controlled surface laser heating on the samples (e.g., liver) while using infrared thermography to record the spatiotemporal temperature evolution.

- Computational Simulation: Simulate the identical experimental setup using both the classical ((\alpha = 1)) and fractional ((0 < \alpha < 1)) bioheat models.

- Model Agreement Assessment: Quantify the agreement between measured and simulated temperature data using:

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

- Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE)

- Residual analysis

- Bland-Altman plots

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform a sensitivity analysis to determine how the fractional order (\alpha) controls the pace of thermal penetration and the extent of predicted thermal zones.

Protocol 2: Coupled Thermal-FSI Analysis of Laser Treatment

This protocol details the setup for a coupled multiphysics simulation to optimize laser treatment for dermatological lesions like neurofibromatosis type 1 [28] [32].

- Problem Definition: Model a three-dimensional geometry of neurofibromatosis-affected skin.

- Laser Parameters: Define a 975 nm diode laser in continuous mode, selected for its optimal penetration within the "therapeutic window" of biological tissue [28].

- Multiphysics Model Setup:

- Optical Module: Implement the diffusion approximation to the radiative transport equation to model laser energy deposition.

- Thermal Module: Solve the transient bioheat equation to obtain the temperature field over a typical exposure time (e.g., 3 seconds).

- FSI Module: Couple the thermal solution to a hyperelastic mechanical model (Ogden/Yeoh) within an ALE formulation to simulate fluid expansion, vaporization, and tissue deformation.

- Simulation and Output: Run the coupled simulation to compute time-dependent fields of temperature, vapor fraction, pressure, and stress.

- Safety Threshold Analysis: Analyze results to ensure intra-tissue pressure remains below critical thresholds (e.g., 817 kPa) to minimize scarring risks, thereby optimizing laser parameters for therapeutic efficacy and safety [28] [32].

Successful implementation of these computational frameworks relies on a suite of software tools and theoretical resources.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| COMSOL Multiphysics [30] | Commercial Software | Finite Element Analysis for coupled physics | Numerical validation of analytical bioheat models; coupled Thermal-FSI simulation. |

| MATHEMATICA [30] | Commercial Software | Symbolic and Numerical Computing | Deriving closed-form analytical solutions for the Pennes bioheat equation. |

| Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) [28] | Numerical Formulation | Handling large deformations and fluid-structure interaction | Core component of a Thermal-FSI framework for tracking deforming skin tissue. |

| Ogden & Yeoh Models [28] | Constitutive Model | Describing nonlinear, hyperelastic material behavior | Representing the large-strain mechanical response of skin tissue in a mechanical simulation. |

| Dirac Delta Function [30] | Mathematical Function | Representing a localized point source of heat | Modeling the highly focused heating of diseased tissue by a laser beam in an analytical solution. |

| Telegraph Equation [30] | Hyperbolic PDE | Modeling damped wave propagation | Incorporating non-Fourier heat conduction effects with finite thermal wave speed in bioheat transfer. |