Illuminating the Future: A Comprehensive Guide to Careers in Biomedical Engineering and Optics

This article provides a detailed exploration of the rapidly converging fields of biomedical engineering and optics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Illuminating the Future: A Comprehensive Guide to Careers in Biomedical Engineering and Optics

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of the rapidly converging fields of biomedical engineering and optics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of these disciplines, explores specialized career paths from medical imaging to biomaterials, addresses key industry challenges and optimization strategies, and validates career decisions through market trends and comparative analysis. The guide synthesizes current data and emerging trends to empower professionals in navigating and advancing their careers at this dynamic technological frontier.

The Convergence of Light and Life: Understanding Biomedical Engineering and Optics

The convergence of engineering principles with biological systems represents a paradigm shift in modern healthcare and scientific research. This synergy, particularly within biomedical engineering and optics, is catalyzing breakthrough innovations in therapeutic development, diagnostic imaging, and precision medicine. By applying quantitative engineering approaches—including optics, photonics, computational modeling, and materials science—to complex biological challenges, researchers are developing transformative solutions that overcome limitations of traditional methodologies. This technical guide examines the core interdisciplinary frameworks driving this integration, with focused analysis on optical manipulation technologies, phototherapy applications, computational drug discovery, and emerging regulatory considerations. The following sections provide detailed experimental protocols, quantitative analyses, and visualization tools essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at this innovative intersection.

Fundamental Synergistic Frameworks

The integration of engineering and biological systems operates through several interconnected mechanistic frameworks that enable precise observation, measurement, and manipulation of biological processes. These frameworks provide the foundation for developing advanced research and therapeutic applications.

Optical and Photonic Engineering applies principles of light-matter interactions to biological systems. Technologies including optical tweezers, photothermal therapy, and fluorescence imaging enable non-invasive manipulation and measurement of cellular and molecular processes [1] [2]. These approaches leverage the unique properties of light to probe biological systems with minimal perturbation, allowing researchers to study mechanisms in native states.

Computational and Modeling Approaches create digital representations of biological systems through finite element analysis, computational fluid dynamics, and multi-scale modeling. These engineering methodologies simulate complex biological phenomena across temporal and spatial scales, from molecular interactions to organ-level systems [3]. Machine learning algorithms further enhance these models by identifying patterns in high-dimensional biological data, enabling predictive analytics for disease progression and therapeutic response.

Materials and Nanoscale Engineering designs biocompatible materials and nanostructures with precisely controlled physical, chemical, and biological properties. These engineered materials interface with biological systems through targeted drug delivery vehicles, tissue engineering scaffolds, and implantable biosensors [2] [4]. By controlling features at nanoscale dimensions, researchers can create systems that mimic natural biological structures and functions.

Table 1: Core Engineering Disciplines and Their Biological Applications

| Engineering Discipline | Key Principles | Biological Applications | Representative Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Engineering | Light-matter interaction, photonics, imaging | Cellular manipulation, molecular detection, intraoperative imaging | Optical tweezers, fluorescence-guided surgery, photodynamic therapy [1] [2] |

| Computational Engineering | Modeling, simulation, data analysis | Drug discovery, protein folding prediction, systems biology | AlphaFold, molecular docking, patient-specific biomechanical models [3] |

| Materials Engineering | Biomaterials, nanotechnology, surface science | Drug delivery, tissue engineering, medical implants | Nanoparticle drug carriers, 3D-bioprinted tissues, biocompatible coatings [2] [4] |

| Mechanical Engineering | Biomechanics, fluid dynamics, thermodynamics | Prosthetics, surgical devices, artificial organs | Exoskeletons, microfluidic organ-on-chip models, heart valves [5] [6] |

Optical Manipulation Technologies in Biomedical Research

Optical manipulation technologies represent a prime example of engineering principles applied to biological investigation. These techniques utilize the momentum transfer of light to precisely control biological specimens without physical contact, enabling novel experimental capabilities.

Core Optical Manipulation Modalities

Optical Tweezers employ highly focused laser beams to generate gradient forces that trap and manipulate microscopic particles, including individual molecules, organelles, and cells [1]. Advanced configurations include holographic optical tweezers that create multiple independent trapping points through wavefront shaping, enabling complex manipulation protocols. Applications in biophysics include single-molecule force measurements on motor proteins like kinesin and myosin, studies of DNA mechanics and chromatin organization, and investigation of cellular mechanical properties through membrane tether formation.

Optofluidics integrates optical control with microfluidic environments to create lab-on-a-chip platforms for high-throughput biological analysis [1]. These systems enable automated sorting, patterning, and analysis of cells and particles within precisely controlled microenvironments. By combining optical forces with fluidic flow, researchers can achieve rapid classification of cellular populations based on optical properties, continuous monitoring of cellular responses to environmental changes, and isolation of rare cells for diagnostic applications.

Photophoresis and Alternative Manipulation Techniques utilize light-induced motion phenomena for specialized applications. Photophoresis exploits radiometric forces generated by non-uniform heating of particles, enabling manipulation of absorbing specimens that challenge conventional optical tweezers [1]. Integration with complementary techniques including acoustic manipulation, magnetic tweezers, and optoelectronic tweezers further expands experimental capabilities for diverse biological samples.

Experimental Protocol: Single-Molecule Biophysics Using Optical Tweezers

The following protocol details methodology for investigating molecular motor mechanics through optical manipulation, representative of approaches used in cutting-edge biophysics research [1]:

Research Objective: Quantify the force generation and stepping mechanics of cytoskeletal motor proteins (e.g., kinesin-1) along microtubule filaments.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified motor protein constructs with engineered attachment handles (e.g., HaloTag or SNAP-tag)

- Microtubules polymerized from tubulin with biotin labels for surface attachment

- Streptavidin-coated polystyrene microspheres (1-3 μm diameter) for trapping

- Anti-GFP antibody-conjugated microspheres for handling GFP-tagged proteins

- ATP regeneration system (ATP, creatine phosphate, creatine kinase)

- Intracellular mimic buffer (e.g., BRB80 with oxygen scavenging system)

Instrumentation Setup:

- Dual-beam optical trapping system with infrared lasers (1064 nm)

- High-numerical aperture water immersion objective (NA ≥1.2)

- Piezo-controlled microscope stage with nanometer precision

- Quadrant photodiode detector with bandwidth >100 kHz

- Inverted microscope configuration with differential interference contrast imaging

Experimental Procedure:

- Sample Chamber Preparation: Create flow chambers (~10-20 μL volume) using paraffin wax and glass coverslips. Introduce biotinylated BSA (0.5 mg/mL), followed by streptavidin (0.5 mg/mL), and finally biotinylated microtubules diluted in assay buffer. Allow 5-minute incubations between steps.

Bead-Protein Conjugation: Incubate antibody-coated trapping beads with purified motor proteins at approximately 1:1 molar ratio for 30 minutes at 4°C. Dilute to appropriate concentration for single-molecule detection.

Optical Trap Calibration: Dilute bead-protein mixture in assay buffer and introduce to chamber. Trap individual beads and calibrate trap stiffness using power spectrum analysis of Brownian motion or drag force methods. Typical stiffness values range from 0.01-0.1 pN/nm.

Data Acquisition: Position trapped bead-motor complex near surface-attached microtubule. Initiate movement by introducing ATP-containing buffer. Record bead position at ≥10 kHz sampling rate while motor proteins move along microtubule track.

Force Measurements: Apply opposing force by moving stage against direction of motor movement. Measure stall force where motor progression ceases. For kinesin-1, expected stall forces approximate 5-7 pN.

Data Analysis:

- Process raw position data using custom algorithms to detect steps (sized ~8 nm for kinesin)

- Calculate force-velocity relationships by varying load forces

- Determine kinetic parameters from dwell-time distributions between steps

- Develop theoretical models matching mechanical and chemical reaction cycles

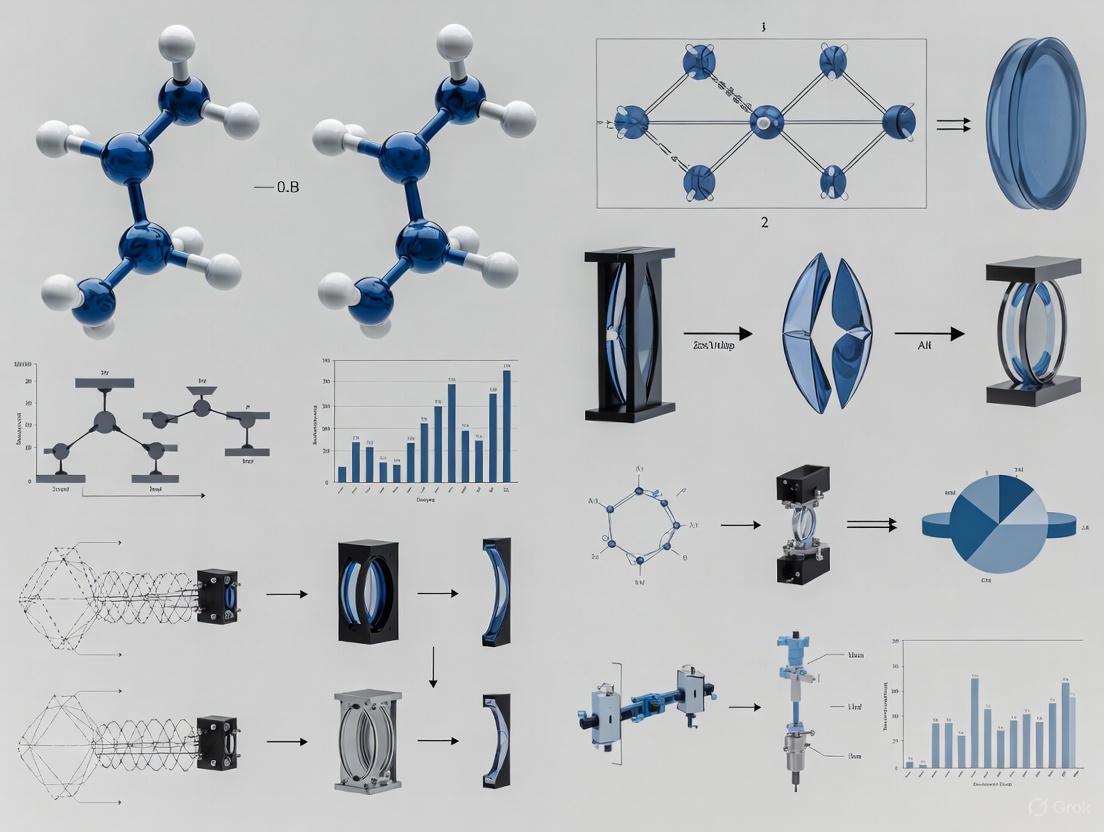

Diagram 1: Optical tweezers experimental workflow for single-molecule biophysics

Phototherapy and Optical Imaging in Therapeutic Applications

Photonic approaches have emerged as powerful therapeutic modalities that exemplify the engineering-biology synergy, particularly in oncology. These technologies leverage light-activated mechanisms to achieve precise spatial and temporal control over treatment effects.

Phototherapy Mechanisms and Applications

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) utilizes photosensitizing agents that generate cytotoxic reactive oxygen species upon light activation [2]. The multi-step process begins with systemic or local administration of photosensitizers that accumulate preferentially in target tissues. Subsequent illumination with specific wavelengths activates these compounds, producing singlet oxygen and other reactive species that induce localized cell death through apoptosis and necrosis pathways. Engineering challenges include optimizing light delivery systems for deep-seated tumors, developing photosensitizers with improved tissue specificity, and controlling oxygen dependency in hypoxic tumor microenvironments.

Photothermal Therapy (PTT) employs light-absorbing nanomaterials that convert photon energy into thermal energy, generating localized hyperthermia that ablates target cells [2]. Noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold nanorods, nanoshells) with tunable surface plasmon resonance properties can be engineered to absorb strongly in the near-infrared tissue transparency window, enabling deeper tissue penetration. The resulting temperature increases (typically to 42-48°C) induce protein denaturation, membrane disruption, and ultimately coagulative necrosis. Engineering advances focus on optimizing photothermal conversion efficiency, developing multimodal agents that combine therapy and imaging, and creating activatable systems that respond to tumor-specific stimuli.

Photochemical Internalization (PCI) represents a more recent approach that light to enhance intracellular drug delivery [2]. This technology utilizes photosensitizers localized in endosomal and lysosomal membranes that, upon illumination, disrupt these compartments through reactive oxygen species generation. This controlled disruption releases therapeutic agents (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids, chemotherapeutics) trapped in endocytic vesicles into the cytosol, significantly enhancing their biological activity. PCI demonstrates particular promise for delivering macromolecular drugs that otherwise exhibit poor endosomal escape efficiency.

Experimental Protocol: Nanoparticle-Mediated Photothermal Therapy

This protocol details methodology for evaluating photothermal therapeutic efficacy using gold nanorods, representative of approaches in translational nanomedicine [2]:

Research Objective: Quantify the photothermal efficiency and cancer cell ablation capability of surface-functionalized gold nanorods.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-capped gold nanorods (peak absorption ~800 nm)

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) conjugation reagents (mPEG-SH, MW 5000)

- Target-specific ligands (e.g., folate, RGD peptides, antibodies) for surface functionalization

- Cancer cell lines with appropriate target receptor expression

- Cell culture media and viability assay reagents (MTT, Calcein-AM/propidium iodide)

- Near-infrared laser system (800 nm wavelength, 0.5-2 W/cm² adjustable power density)

Nanoparticle Functionalization:

- PEGylation: Incubate CTAB-stabilized nanorods (1 nM) with mPEG-SH (100 μM) for 12 hours at room temperature with gentle stirring. Remove excess PEG through centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 15 minutes) and resuspend in phosphate buffer.

- Targeting Ligand Conjugation: React PEGylated nanorods with heterobifunctional PEG derivatives (e.g., NHS-PEG-Maleimide) for 2 hours. Purify and incubate with thiolated targeting ligands (1:100 molar ratio) overnight at 4°C.

- Characterization: Verify surface modification through zeta potential measurements, spectrophotometric analysis of surface plasmon resonance shifts, and dynamic light scattering for hydrodynamic size determination.

In Vitro Photothermal Efficacy:

- Cellular Uptake Studies: Incubate target cells with functionalized nanorods (0.1 nM) for 2-24 hours. Quantify internalization through atomic absorption spectroscopy, darkfield microscopy, or flow cytometry of scattering signals.

- Photothermal Treatment: Plate cells in 96-well plates (10,000 cells/well) and incubate with nanorods for 6 hours. Wash to remove uninternalized particles. Illuminate with NIR laser (800 nm, 1 W/cm²) for 5-10 minutes. Monitor temperature changes using infrared thermal camera.

- Viability Assessment: Perform MTT assay 24 hours post-illumination to quantify metabolic activity. Conduct live/dead staining (Calcein-AM/propidium iodide) for direct visualization of treatment effects. Compare to controls including cells only, nanorods only, and laser only.

Mechanistic Investigations:

- Analyze apoptosis induction through Annexin V/propidium iodide flow cytometry

- Examine cellular morphology changes via transmission electron microscopy

- Measure heat shock protein expression (HSP70, HSP90) through western blotting

- Evaluate mitochondrial membrane potential disruption using JC-1 staining

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Photothermal Therapy Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photothermal Nanomaterials | Gold nanorods, nanoshells, carbon nanotubes | Light absorption and heat generation | Tunable plasmon resonance, high photothermal conversion efficiency, biocompatibility [2] |

| Surface Modification Agents | mPEG-SH, PEG-phospholipids, heterobifunctional linkers | Improve biocompatibility and targeting | Stealth properties, reduced protein adsorption, functional groups for ligand attachment [2] |

| Targeting Ligands | Folate, RGD peptides, transferrin, monoclonal antibodies | Specific recognition of target cells | High affinity for receptors overexpressed on target cells, appropriate conjugation chemistry [2] |

| Characterization Tools | Dynamic light scattering, UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy, electron microscopy | Nanoparticle physicochemical characterization | Size distribution, surface charge, optical properties, morphology determination [2] |

| Biological Assessment | MTT assay, live/dead staining, Annexin V apoptosis kit | Evaluation of therapeutic efficacy and mechanisms | Metabolic activity, membrane integrity, apoptosis pathway activation [2] |

Computational and AI-Driven Integration in Biomedical Research

Artificial intelligence and computational modeling have dramatically accelerated the integration of engineering principles with biological discovery, particularly in pharmaceutical development and systems biology.

AI-Enhanced Drug Discovery Pipelines

Target Identification and Validation leverages machine learning algorithms to integrate multi-omics datasets, literature mining, and experimental data for prioritizing therapeutic targets [3]. Platforms such as PandaOmics employ deep learning and natural language processing to analyze gene expression patterns, protein-protein interactions, and genetic association studies across thousands of diseases. This systems biology approach identifies not only individual targets but also complex pathway dependencies and network vulnerabilities. For ophthalmology applications, AI-driven target discovery has accelerated identification of novel pathways in geographic atrophy and diabetic retinopathy, conditions with limited treatment options.

Structure-Based Drug Design utilizes computational prediction of protein structures and molecular docking simulations to optimize therapeutic compounds [3]. The AlphaFold system represents a transformative engineering achievement, accurately predicting protein three-dimensional structures from amino acid sequences using deep neural networks. These structural predictions enable virtual screening of compound libraries against target proteins, significantly reducing the experimental burden of high-throughput screening. Subsequent molecular dynamics simulations model drug-target interactions with atomic resolution, providing insights into binding kinetics, conformational changes, and residence times that inform lead optimization.

Clinical Trial Optimization applies AI algorithms to improve patient stratification, endpoint selection, and trial efficiency [3]. Machine learning models trained on electronic health records, medical images, and genomic data can identify patient subgroups most likely to respond to investigational therapies. In ophthalmology drug development, AI analysis of retinal images enables quantitative tracking of disease progression, providing sensitive biomarkers for clinical trial endpoints. These computational approaches have demonstrated potential to reduce clinical trial durations and improve success rates through enhanced experimental design.

Experimental Protocol: AI-Guided Drug Discovery for Ocular Diseases

This protocol outlines a computational framework for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutics for ocular disorders, representing cutting-edge approaches in digital drug discovery [3]:

Research Objective: Identify and computationally validate novel inhibitors of angiogenesis for treatment of diabetic retinopathy.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Multi-omics datasets (transcriptomics, proteomics) from diabetic retinopathy patient samples

- Structural databases (Protein Data Bank, AlphaFold Protein Structure Database)

- Compound libraries (ZINC, ChEMBL, in-house collections)

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD)

- Molecular dynamics simulation packages (AMBER, GROMACS, Desmond)

- AI platforms for target discovery (PandaOmics, IBM Watson for Drug Discovery)

Computational Workflow:

Target Identification:

- Collect and preprocess transcriptomic data from public repositories (GEO, ArrayExpress) and proprietary diabetic retinopathy datasets

- Apply PandaOmics AI platform to analyze differential expression, pathway enrichment, and disease association

- Prioritize targets based on novelty, druggability, and network centrality scores

- Validate target selection through literature mining and expression profiling in ocular tissues

Structure Preparation:

- Retrieve three-dimensional structure of prioritized target from PDB or generate using AlphaFold2

- Prepare protein structure through hydrogen atom addition, assignment of protonation states, and optimization of hydrogen bonding networks

- Define binding site based on experimental data or computational prediction

Virtual Screening:

- Prepare compound library through structure standardization, tautomer enumeration, and generation of 3D conformers

- Perform high-throughput docking using validated parameters and scoring functions

- Select top candidates based on docking scores, binding poses, and interaction patterns

- Apply machine learning models to predict ADMET properties and prioritize compounds with favorable pharmacological profiles

Molecular Dynamics Validation:

- Solvate top-ranked ligand-protein complexes in explicit water boxes with appropriate ions

- Perform energy minimization and equilibration using standard protocols

- Conduct production simulations (100-200 ns) with periodic boundary conditions

- Analyze trajectory data for binding stability, interaction persistence, and conformational changes

- Calculate binding free energies using MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA methods

Experimental Collaboration:

- Synthesize or procure top computational candidates for experimental validation

- Design in vitro assays to confirm target engagement and functional activity

- Evaluate cytotoxicity and specificity in relevant ocular cell models

- Iteratively refine computational models based on experimental results

Diagram 2: AI-driven drug discovery workflow for ocular therapeutics

Career Pathways at the Engineering-Biology Interface

The integration of engineering and biological systems has created diverse career opportunities that leverage interdisciplinary expertise. These roles span academic research, industrial development, clinical implementation, and regulatory affairs.

Emerging Professional Roles

Medical Device and Imaging Engineers design, develop, and optimize technologies that interface directly with biological systems [5] [6] [4]. These professionals combine knowledge of physiological principles with engineering design to create diagnostic and therapeutic devices. Specializations include optical imaging system development, surgical robotics, wearable sensors, and point-of-care diagnostics. The expanding regulatory framework for optical imaging drugs described in FDA draft guidance further drives demand for engineers who can navigate the device-drug combination product landscape [7] [8].

Computational Biomedical Specialists develop and apply algorithms, models, and data analysis approaches to biological challenges [5] [6] [3]. Roles include bioinformaticians who analyze genomic and proteomic datasets, computational biologists who model biological networks, and AI specialists who develop predictive algorithms for therapeutic discovery. These positions require strong computational backgrounds alongside understanding of biological principles, with particular demand for professionals skilled in machine learning applications for healthcare.

Regulatory Science and Clinical Engineering professionals ensure that biomedical technologies meet safety and efficacy standards while facilitating their translation to clinical use [5] [6]. Clinical engineers manage medical equipment in healthcare settings, while regulatory affairs specialists navigate approval processes for new technologies. The January 2025 FDA draft guidance on developing optical imaging drugs highlights the growing regulatory complexity for combination products, creating demand for professionals with both technical and regulatory expertise [7] [8].

Table 3: Quantitative Career Outlook in Biomedical Engineering Specializations

| Specialization Area | Median Salary Range | Projected Growth (2024-2034) | Key Industry Sectors | Typical Educational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Device Design & Development | $86,586 (U.S. average) [5] | 5% (faster than average) [6] | Medical device companies, biotechnology firms, startups | Bachelor's minimum, Master's preferred for R&D roles |

| Clinical Engineering | $89,338 (U.S. average) [5] | 5% (faster than average) [6] | Hospitals, healthcare systems, equipment manufacturers | Bachelor's with clinical engineering certification |

| Biomedical Imaging & AI Analytics | $106,950 (median for bioengineers) [6] | 12% (medical device sector) [5] | Imaging equipment manufacturers, AI diagnostics companies, research institutions | Master's or PhD for research positions |

| Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine | Varies by role: $85,000-$120,000 | 5% (faster than average) [6] | Biotech, pharmaceutical companies, academic research centers | PhD typically required for research leadership |

| Bioinformatics & Computational Biology | $150,000-$170,000 (experienced with MS/PhD) [5] | Rapid expansion [5] | Pharmaceutical R&D, genomics companies, research institutions | Master's or PhD with computational focus |

Professional Development Framework

Educational Pathways for careers at the engineering-biology interface typically begin with undergraduate degrees in biomedical engineering, bioengineering, or related disciplines [6] [4]. Foundational coursework integrates biological sciences with engineering principles, often complemented by laboratory research experiences. Advanced positions frequently require graduate education, with master's and doctoral programs providing specialized training in areas such as neural engineering, biomaterials, medical optics, or computational biology. Professional master's programs increasingly emphasize industry-relevant skills and include capstone projects addressing real-world challenges.

Skill Development beyond core technical competencies includes interdisciplinary communication, project management, and regulatory knowledge [6]. Professionals must effectively translate between engineering and biological paradigms, requiring fluency in both domains. Experimental design skills must incorporate considerations of biological variability, ethical requirements, and clinical translation pathways. Familiarity with regulatory frameworks, such as the FDA guidance on optical imaging drugs, becomes increasingly important for roles involved in product development [7] [8].

Research Training experiences provide critical preparation for careers at this interface [9] [10]. Programs such as the Synergy Summer Studentship at UBC offer structured research experiences that integrate professional development with laboratory investigation [9]. These opportunities enable trainees to apply engineering approaches to biological questions while developing technical and professional skills. Similar research internships and training programs are offered by institutions including Harvard Medical School, Oregon Health & Science University, and the National Institutes of Health [10].

Regulatory and Commercialization Landscape

The translation of technologies emerging from engineering-biology integration requires navigation of evolving regulatory pathways and commercialization challenges.

Regulatory Considerations for Combination Products

Technologies that combine engineering platforms with biological components frequently fall under regulatory frameworks for combination products [7] [8]. The January 2025 FDA draft guidance "Developing Drugs for Optical Imaging" addresses one category of these products, providing recommendations for clinical trial design of optical imaging drugs used with imaging devices during surgical procedures [7] [8]. This guidance highlights several key considerations:

Clinical Trial Design must demonstrate that optical imaging drugs enhance surgeons' ability to identify pathological tissues while maintaining safety profiles [7] [8]. Endpoints typically include sensitivity and specificity for target detection compared to standard visual inspection and palpation. Trials must account for intended use population, procedure type, and clinical context, with specific considerations for molecularly targeted fluorescent agents that highlight tumor margins.

Device-Drug Integration requires coordinated development of both components, with testing to demonstrate compatibility and performance [7] [8]. The guidance emphasizes that imaging device characteristics including illumination intensity, detection sensitivity, and spatial resolution directly impact drug performance and must be appropriately controlled and documented.

Labeling and Instructions for Use must provide clear guidance on proper administration, imaging timing relative to drug dosing, and device operation parameters [7] [8]. This information ensures that the combined product delivers consistent performance across clinical settings and user expertise levels.

Commercialization Pathways

Technology Transfer from academic research to commercial development requires strategic intellectual property protection and licensing [6] [4]. Technologies with strong patent positions and clear regulatory pathways attract greater investment and have higher translation potential. The expanding definition of biomedical engineering into optics, AI, and nanotechnology creates new intellectual property opportunities at discipline intersections.

Market Analysis must assess clinical need, competitive landscape, reimbursement considerations, and adoption barriers [6] [4]. Technologies addressing unmet needs in areas such as cancer surgery, rare diseases, or diagnostic challenges may receive expedited regulatory review and premium reimbursement. The $66 billion global ophthalmic drug market exemplifies the economic potential for targeted technologies in specific therapeutic areas [3].

Business Models for engineering-biology technologies vary from traditional medical device approaches to software-as-a-service platforms for AI diagnostics [6] [4]. Companies developing combination products must establish quality systems that address both device and drug regulatory requirements, creating operational complexity that requires specialized expertise.

Future Directions and Emerging Opportunities

The synergy between engineering and biological systems continues to evolve, driven by technological advances and unmet medical needs. Several emerging areas represent particularly promising frontiers for research and development.

Integrated Theragnostic Platforms combine diagnostic capabilities with therapeutic interventions in closed-loop systems [2]. These platforms utilize biosensors to monitor disease states or treatment responses, with algorithms that adjust therapeutic interventions in real time. Examples include glucose-responsive insulin delivery systems and implantable devices that detect and terminate cardiac arrhythmias. Optical technologies contribute through miniaturized sensors, light-based actuation mechanisms, and non-invasive monitoring approaches.

Neuroengineering Innovations interface engineering systems with neural circuits to restore function following injury or disease [5] [6] [4]. Advancements in brain-computer interfaces, neuroprosthetics, and neuromodulation therapies create new opportunities for treating conditions including paralysis, Parkinson's disease, and psychiatric disorders. Optical methods such as optogenetics enable precise control of specific neural populations, while optical imaging provides detailed functional mapping of neural activity.

Sustainable Biomedical Engineering addresses environmental impacts of medical technologies while expanding global healthcare access [6]. Developments include biodegradable implants, low-power medical devices for resource-limited settings, and point-of-care diagnostics that function without sophisticated laboratory infrastructure. These approaches apply engineering principles to optimize healthcare delivery while minimizing ecological footprint.

Digital Health Integration connects biomedical devices with data analytics platforms to enable continuous health monitoring and personalized interventions [6] [3]. Wearable sensors, smartphone-based diagnostics, and remote monitoring systems generate high-frequency data streams that, when analyzed with machine learning algorithms, can detect early disease signatures and guide preventive interventions. The validation of these digital biomarkers represents an active area of research and regulatory development.

The continued convergence of engineering and biological systems promises to transform healthcare through more precise, personalized, and accessible technologies. Professionals working at this interface will drive innovations that address fundamental biological challenges through engineering principles, creating solutions that benefit patients worldwide.

Biomedical engineering stands as one of the fastest-evolving fields, uniquely blending medicine, biology, and technology to develop advanced healthcare solutions [5]. This discipline empowers professionals to innovate across a spectrum of areas—from medical devices and diagnostic tools to prosthetics and regenerative therapies [5]. As healthcare demands grow and technology accelerates, specialization within biomedical engineering has become increasingly critical. Specializations enable engineers to develop deep expertise in high-demand areas, opening doors to leadership roles in research, product development, and healthcare technology management [5]. For researchers and scientists in drug development, understanding these sub-fields is essential for leveraging cutting-edge engineering principles to advance therapeutic discovery, diagnostic precision, and clinical implementation. This guide provides a technical examination of core specializations, with particular focus on bioinstrumentation and biomedical optics, framing them within the context of career opportunities and research applications in the evolving biomedical landscape.

Core Sub-Fields and Specializations

Biomedical engineering encompasses a diverse array of sub-fields, each targeting specific challenges in medicine and biology. The table below summarizes the most in-demand specializations, their core focus areas, and associated career paths that are pivotal for researchers and scientists.

Table 1: Core Specializations in Biomedical Engineering

| Specialization | Core Focus & Technologies | Example Career Paths & Research Roles |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinstrumentation & Medical Device Design [5] [11] | Design of medical devices and instruments; surgical robots, wearable sensors, diagnostic tools [5] [11]. | Product Design Engineer, R&D Engineer, Manufacturing Engineer [5]. |

| Biomedical Imaging & Optics [5] [12] | Development of medical imaging systems (MRI, CT, ultrasound, OCT); image processing algorithms, AI analytics for enhanced diagnostics [5] [13] [12]. | Imaging Systems Engineer, Research Scientist, Clinical Imaging Specialist [5]. |

| Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine [5] [12] | Application of biomaterials, stem cells, and 3D bioprinting to develop artificial tissues and organs [5] [12]. | Research Scientist, Bioprocess Engineer, Clinical Trials Manager [5]. |

| Biomechanics & Rehabilitation Engineering [5] [14] | Study of mechanical forces in biological systems; design of prosthetics, orthotics, and exoskeletons [5] [14]. | Prosthetics Designer, Rehabilitation Engineer, Sports Biomechanist [5]. |

| Biomaterials Engineering [5] | Development of safe and effective materials for implants, scaffolds, and drug delivery systems [5]. | Biomaterials Scientist, Implant Designer, Drug Delivery Engineer [5]. |

| Systems and Synthetic Biology [15] | Engineering principles to understand, design, and build cellular-level biological systems; engineered cells for therapy [15]. | Research Scientist, Bioengineer, Biotech Entrepreneur. |

| Neural Engineering [5] | Focus on the nervous system; development of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and neuroprosthetics [5]. | Neuroprosthetics Engineer, BCI Developer, Neuroengineering Researcher [5]. |

| Clinical Engineering & Regulatory Affairs [5] [14] | Ensuring medical device safety, efficacy, and regulatory compliance in healthcare settings [5] [14]. | Clinical Engineer, Regulatory Affairs Specialist, Healthcare Technology Manager [5]. |

Quantitative Analysis of Field

Quantitative data reveals the growing prominence and economic viability of specialized research areas within biomedical engineering. A systematic review of PubMed-indexed studies from 2018-2022 identified a statistically significant yearly increase in research utilizing anonymized biomedical data, a proxy for data-intensive fields like bioinformatics and medical imaging [16]. This trend underscores a broader movement towards computational and data-driven methodologies. Furthermore, geographical analysis of this research output indicates that the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia lead in the volume of studies employing shared anonymized data, suggesting mature research ecosystems and possibly more established regulatory pathways in these regions [16]. For the career-focused researcher, specializations like Medical Device Design, Clinical Engineering, and Bioinformatics are noted for offering a high return on investment (ROI) due to their strong industry demand and earning potential [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Trends and Return on Investment (ROI) in Key Specializations

| Specialization | Research Growth & Prevalence | Reported Salary and ROI Data |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Device Design & Development [5] | World demand expected to increase by 12% over the next decade [5]. | U.S. average salary: $86,586 (25th-75th percentile: $79,133 - $91,182) [5]. |

| Clinical Engineering [5] | Critical role in hospital operations and patient safety [5] [14]. | U.S. average salary: $89,338 (typical range: $79,873 - $99,169) [5]. |

| Bioinformatics & Data Science [5] | Taps into booming demand for data expertise in genomics and personalized medicine [5]. | Experienced bioinformaticians (MS/PhD) can earn $150,000 - $170,000 in competitive industry roles [5]. |

| Biomedical Engineering (General) [14] | Employment projected to grow 5% from 2022 to 2032 [14]. | Median annual wage: $108,060 [14]. |

Detailed Examination: Bioinstrumentation

Core Principles and Methodologies

Bioinstrumentation focuses on the design and development of devices and instruments used in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease [11]. This sub-field integrates principles from electronics, mechanics, and computer science with biological sciences to create tools that range from simple diagnostic equipment to complex, life-supporting systems [11]. A core methodological workflow in bioinstrumentation involves sensing a physiological signal, conditioning the acquired data, processing and analyzing the information, and finally presenting the results in a usable format for clinical or research decision-making.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A fundamental protocol in bioinstrumentation is the design and testing of a wearable biosensor for physiological monitoring, which exemplifies the integration of multiple engineering disciplines.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for a Wearable Biosensor Prototype

| Item / Material | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Flexible Substrate (e.g., PDMS) | Serves as the base material for the wearable sensor, providing conformability to the skin and patient comfort. |

| Electrophysiological Sensors (e.g., Ag/AgCl Electrodes) | Act as the transducer to capture biopotential signals (e.g., ECG, EMG) from the body's surface. |

| Microcontroller Unit (MCU) | The core "brain" that manages data acquisition from the sensors, preliminary signal processing, and data transmission. |

| Signal Conditioning Circuitry | Comprises amplifiers, filters, and analog-to-digital converters (ADC) to enhance signal quality and prepare it for digital processing. |

| Wireless Communication Module (e.g., Bluetooth Low Energy) | Enables the transmission of processed physiological data to a remote terminal such as a smartphone or laptop for visualization and analysis. |

| Bench-Top Signal Simulator | Used for initial validation and calibration of the sensor system by generating known, precise electrical signals that mimic physiological outputs. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow in the development and validation of a bioinstrumentation device, from concept to preclinical testing.

Diagram 1: Bioinstrumentation Device Development Workflow

Detailed Examination: Biomedical Optics

Core Principles and Methodologies

Biomedical optics offers a non-invasive window into the intricate workings of the human body, revolutionizing medical diagnostics and treatment monitoring [12]. This sub-field leverages light and optical technologies to visualize internal structures, physiological processes, and metabolic activity [15] [12]. Key modalities include Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), which provides high-resolution, cross-sectional imaging of tissue microstructures; diffuse optical imaging for assessing tissue oxygenation and metabolism; and various forms of clinical spectroscopy [13] [12]. Advances in AI and machine learning are now paving the way for more detailed and faster image analysis, while techniques like molecular imaging are creating new possibilities for early detection and personalized treatment strategies [5] [12].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A representative and cutting-edge protocol in this field involves the use of Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography (SS-OCT) for high-resolution, volumetric imaging of biological tissues [13]. The following diagram outlines the core components and signal processing pathway of an SS-OCT system.

Diagram 2: Swept-Source OCT System Dataflow

The experimental workflow for an SS-OCT study, such as measuring eardrum vibrations or creating large-area images, involves several key stages [13]. The process begins with System Calibration and Phase Stabilization, which is critical for achieving high-quality, reliable data. Recent research focuses on novel phase stabilization techniques to mitigate environmental perturbations [13]. Next, Data Acquisition involves scanning the sample using specific raster scanning patterns (e.g., stripe-like scanning for large areas) [13]. The light backscattered from the sample and reflected from the reference mirror generates an interference pattern, which is captured by the photodetector and digitized. Signal Processing is then performed, which includes Fourier transformation to convert the raw spectral data into depth-resolved (A-scan) information. Multiple A-scans are combined to form cross-sectional (B-scan) or volumetric (3D) images. Finally, Image Analysis and Interpretation is conducted, often leveraging algorithms for tasks like segmenting specific tissue layers or quantifying vibrational amplitudes.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SS-OCT Experimentation

| Item / Material | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Swept-Source Laser | The light source that rapidly tunes its wavelength over a broad range, defining the axial resolution and imaging depth of the system. |

| Single-Mode Optical Fiber & Couplers | The network for guiding and splitting the laser light between the reference and sample arms of the interferometer. |

| High-Speed Photodetector & Digitizer | Captures the weak interference signal and converts it from an analog to a digital format for subsequent computation. |

| Galvanometric Scanning Mirrors | Precisely steer the sample beam to scan it across the tissue surface in a defined raster pattern. |

| Computational Hardware (e.g., Raspberry Pi) | Used for system control, initial data processing, and potentially for adapting systems into more compact, cost-effective formats [13]. |

| Spectral Analysis Software | Essential for calibrating the laser, detecting its optical sweeping direction, and processing the raw k-space data into meaningful images [13]. |

Career Pathways and Convergence with Optics Research

The specializations of bioinstrumentation and biomedical optics offer robust and diverse career paths for researchers and scientists. Professionals can find opportunities in academic research, industrial research and development (R&D), clinical environments, and government agencies [5] [12]. In the industrial sector, biomedical engineers work for medical device manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, and biotech startups, with responsibilities spanning device design, procedure development, and clinical problem-solving [12]. The entrepreneurial sector is particularly vibrant, with startups serving as innovation hubs for emerging technologies [11].

The convergence of biomedical engineering with optics and photonics research is a particularly dynamic frontier. Professional organizations like Optica and SPIE actively foster this interdisciplinary community, sponsoring major conferences such as the European Conferences on Biomedical Optics (ECBO) that cover topics from advanced microscopy and spectroscopy to OCT and therapeutic laser applications [13]. These gatherings are critical for networking, sharing breakthroughs, and career development for early-career professionals [17] [13]. The job market for optical engineering skills is broad, with roles including Optical Engineer, Systems Engineer, Optical Designer, and Application Engineer, many of which are directly applicable to the medical device and imaging industries [18]. For those in drug development and research, collaborating with or becoming an expert in biomedical optics means gaining access to powerful tools for non-invasive, high-resolution imaging that can accelerate therapeutic evaluation and fundamental biological understanding.

The convergence of photonics and biomedical devices is creating a paradigm shift in modern healthcare, enabling breakthroughs in diagnostics, treatment, and patient monitoring. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of growth projections in these synergistic fields, framed within the context of career opportunities for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Photonics, the science of generating, detecting, and manipulating light, is becoming increasingly integral to biomedical innovation, from advanced imaging systems to minimally invasive surgical tools. We examine quantitative market data, detail experimental methodologies underpinning key technologies, and visualize the interdisciplinary workflows driving this expansion. For professionals in biomedical engineering and optics research, understanding these trends is crucial for positioning themselves at the forefront of medical technology innovation. The integration of light-based technologies with biological systems is not only expanding diagnostic capabilities but also creating new pathways for therapeutic development and personalized medicine.

The photonics and biomedical device markets are experiencing robust growth globally, driven by technological advancements, increasing healthcare demands, and the rising prevalence of chronic diseases. This section provides a detailed quantitative analysis of current market sizes and future projections.

Table 1: Global Photonics Market Projections (2023-2032)

| Metric | 2023/2024 Value | Projected Value | Time Period | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Photonics Market | $920.56 billion (2023) [19] | $1,642.61 billion [19] | 2024-2032 [19] | 6.7% [19] | Non-invasive healthcare, additive manufacturing, surveillance & biometric ID [19] |

| U.S. Photonics Market | $142.55 billion (2024) [20] | $221.33 billion [20] | 2024-2033 [20] | 5.01% [20] | Telecommunications, healthcare, defense, consumer electronics [20] |

| Alternative Global Photonics View | $988.71 billion (2025) [21] | $1,733.49 billion [21] | 2025-2035 [21] | 5.8% [21] | High-speed data transmission, laser tech advancements, AI integration [21] |

| Silicon Photonics Market | $2.86 billion (2025) [22] | $28.75 billion [22] | 2025-2034 [22] | 29.25% [22] | Data center demand, CMOS compatibility, faster data transfer [22] |

Table 2: Global Medical Device Market Projections (2024-2030)

| Metric | 2024/2025 Value | Projected Value | Time Period | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Medical Device Market | $542.21 billion (2024) [23] | $886.80 billion [23] | 2024-2032 [23] | Not specified | Aging population, chronic disease rise, technological innovation [23] [24] |

| Alternative Medical Device View | $681.57 billion (2025) [24] | $955.49 billion [24] | 2025-2030 [24] | 6.99% [24] | Aging population, chronic diseases, AI & robotics integration [24] |

| Connected Medical Devices | $75.99 billion (2025) [24] | $152.71 billion [24] | 2025-2030 [24] | 14.98% [24] | IoT integration, remote patient monitoring, telemedicine [23] [24] |

| Wearable Medical Devices | Not specified | $66.9 billion [24] | Through 2030 [24] | 10.1% [24] | Real-time monitoring, chronic disease management [23] [24] |

Regional analysis reveals that Asia Pacific dominates the global photonics market with a 63.2% share as of 2023, valued at $581.75 billion [19]. This dominance is attributed to strong R&D investments, domestic production capabilities, and extensive export supply chains, particularly in China [19]. Meanwhile, North America leads in medical devices, contributing over 40% to global revenues, driven by high healthcare expenditure, advanced infrastructure, and a robust innovation ecosystem [23] [24].

The silicon photonics segment deserves special attention as it represents the fastest-growing subsector with a remarkable 29.25% CAGR [22]. This technology, which integrates optical components with silicon-based electronics, is particularly relevant for biomedical applications including biosensing, DNA sequencing, and advanced imaging systems [22]. The compatibility with mainstream CMOS manufacturing makes it attractive for scaling and volume production of miniaturized medical devices [22].

Key Technologies and Experimental Methodologies

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) in Biomedical Imaging

Optical Coherence Tomography has revolutionized diagnostic imaging, particularly in ophthalmology and oncology. OCT functions as the "optical equivalent of ultrasound," using light waves instead of sound waves to capture micrometer-resolution, cross-sectional images of biological tissues [19]. The methodology below details the standard protocol for OCT imaging in clinical research.

Experimental Protocol: OCT for Retinal Imaging

Sample Preparation:

- Dilate patient's pupils using tropicamide (0.5%) or phenylephrine (2.5%)

- Position patient comfortably with chin stabilized in chinrest and forehead against headband

- Ensure proper alignment to maintain consistent distance from imaging lens

System Calibration:

- Verify reference mirror position in Michelson interferometer setup

- Calibrate wavelength of super-luminescent diode source (typically 800-1300nm)

- Adjust detector sensitivity and scan depth according to tissue type

Image Acquisition:

- Initiate scanning protocol with appropriate resolution settings (axial: 3-7μm, transverse: 10-20μm)

- Acquire multiple B-scans (cross-sectional images) at regions of interest

- Apply tracking algorithms to compensate for patient motion artifacts

Signal Processing:

- Perform Fourier transform on interferometric data to reconstruct depth-resolved profiles

- Apply dispersion compensation algorithms to improve image resolution

- Utilize noise reduction techniques to enhance signal-to-noise ratio

Image Analysis:

- Segment retinal layers using automated algorithms or manual annotation

- Quantify layer thicknesses and identify pathological alterations

- Generate thickness maps for comparative analysis across patient populations

The integration of OCT scanning in ophthalmology has been particularly transformative, enabling detection of glaucoma, retinopathy, and other retinal conditions that were previously challenging to diagnose [19]. Recent advancements in OCT technology have also expanded applications to intravascular imaging, dermatological assessment, and cancer margin detection during surgical procedures.

Diagram 1: OCT imaging workflow for biomedical research

Photonic Biosensors for Diagnostic Applications

Photonic biosensors represent a rapidly advancing field where photonic principles are applied to detect biological molecules with high sensitivity and specificity. These devices are particularly valuable for point-of-care testing, therapeutic drug monitoring, and biomarker discovery in drug development.

Experimental Protocol: Silicon Photonic Biosensor for Protein Detection

Chip Functionalization:

- Clean silicon photonic chip with oxygen plasma treatment

- Immerse in 2% (v/v) 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) in ethanol for 1 hour

- Rinse with ethanol and cure at 110°C for 10 minutes

- Activate surface with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 2 hours

Probe Immobilization:

- Incubate with specific antibody solution (100μg/mL in PBS) overnight at 4°C

- Block nonspecific binding sites with 1% BSA for 1 hour

- Rinse with PBS-Tween 20 (0.05%) to remove unbound antibodies

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute patient samples in appropriate buffer (serum, plasma, or buffer)

- Centrifuge at 10,000g for 10 minutes to remove particulate matter

- Adjust pH to 7.4 if necessary for optimal binding conditions

Detection Protocol:

- Flow sample over functionalized sensor surface at controlled rate (10-100μL/min)

- Monitor wavelength shift in resonance peak due to binding events

- Record binding kinetics in real-time for 15-30 minutes

- Regenerate surface with glycine-HCl (pH 2.5) between measurements

Data Analysis:

- Calculate concentration from calibration curve of known standards

- Determine binding affinity (KD) from kinetic analysis of association/dissociation

- Perform statistical analysis across replicate measurements

The emergence of silicon photonic biosensors is particularly significant, leveraging the mature CMOS manufacturing infrastructure to create highly sensitive, multiplexed detection platforms [22]. These devices are finding applications in monitoring therapeutic drug levels, detecting cancer biomarkers, and diagnosing infectious diseases with minimal sample volumes.

Career Pathways and Research Directions

Interdisciplinary Career Opportunities

The convergence of photonics and biomedical devices has created diverse career pathways for researchers and engineers. Understanding these roles is essential for professionals seeking to position themselves in this expanding market.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Biomedical Photonics

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Silicon Chips | Platform for biosensor development | Protein detection, DNA hybridization studies [22] |

| Near-Infrared Fluorophores | Contrast agents for deep tissue imaging | Optical coherence tomography, fluorescence-guided surgery [19] |

| Biocompatible Optical Polymers | Waveguides for implantable devices | Continuous monitoring sensors, optogenetic interfaces [20] |

| Quantum Dot Probes | Photostable biomarkers for multiplexed detection | Cellular imaging, in vitro diagnostics [21] |

| Photoactivatable Reagents | Spatiotemporal control of biological processes | Targeted drug delivery, photodynamic therapy [19] |

Biomedical engineers specializing in photonics enjoy strong employment prospects, with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projecting 5% job growth until 2032 [25]. These professionals command competitive salaries, with a median annual pay of $106,950 for bioengineers and biomedical engineers [25]. The field supports over 1.32 million people worldwide in photonics components production alone, with manufacturing of photonics-enabled products generating more than five million jobs globally [26].

Diagram 2: Career pathways in biomedical engineering and optics

Emerging Research Frontiers

Several cutting-edge research domains are poised to shape the future of biomedical photonics, offering significant opportunities for scientific advancement and career specialization:

Integrated Photonic Point-of-Care Diagnostics: The miniaturization of complex laboratory functions onto photonic chips represents a paradigm shift in diagnostic testing. Researchers are developing silicon photonic biosensors that can detect multiple biomarkers simultaneously from minute sample volumes [22]. These devices leverage the evanescent field of light guided in nanoscale waveguides to probe molecular interactions at the sensor surface. For drug development professionals, these platforms offer new approaches to therapeutic monitoring and companion diagnostics.

AI-Enhanced Photonic Imaging: The integration of artificial intelligence with photonic imaging systems is revolutionizing image interpretation and diagnostic accuracy. Machine learning algorithms are being developed to automatically analyze OCT scans, detecting subtle pathological features that may escape human observation [21] [19]. Research in this area requires interdisciplinary collaboration between optical engineers, computer scientists, and clinical specialists to develop robust algorithms validated on diverse patient populations.

Neuromodulation and Optogenetics: Photonic technologies are enabling precise manipulation of neural activity using light-sensitive ion channels and pumps. Optogenetic interfaces combine microfabricated light sources with genetic targeting of specific neuronal populations, creating powerful tools for investigating neural circuits and developing novel therapeutic approaches for neurological disorders. This research frontier requires expertise in optics, genetics, neuroscience, and medical device design.

Therapeutic Laser Applications: Advancements in laser technology are expanding therapeutic applications beyond traditional surgical uses. Selective photothermolysis techniques are being refined to target specific structures (e.g., blood vessels, pigmented lesions) while minimizing damage to surrounding tissue. Meanwhile, photodynamic therapy continues to evolve with improved photosensitizers and light delivery systems for cancer treatment. Research in this domain focuses on optimizing light-tissue interactions for maximal therapeutic efficacy.

The synergistic expansion of photonics and biomedical devices represents one of the most dynamic frontiers in healthcare technology. Market projections consistently demonstrate robust growth across both sectors, with particular acceleration in specialized segments including silicon photonics, connected medical devices, and wearable health monitors. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this convergence creates unprecedented opportunities to develop innovative solutions to pressing healthcare challenges.

The continued integration of photonic technologies into biomedical applications—from advanced imaging systems to point-of-care diagnostics—is fundamentally transforming patient care and biomedical research methodologies. Success in this interdisciplinary field requires researchers to develop expertise spanning photonics engineering, biological sciences, and clinical applications. Those who can navigate this complex landscape will be well-positioned to contribute to the next generation of biomedical innovations that leverage the unique capabilities of light-based technologies to improve human health.

Key Industry Players and Research Institutions Driving Innovation

The fields of biomedical engineering and optics are increasingly intertwined, driving a wave of innovation that is transforming modern healthcare. This synergy is accelerating advancements in diagnostics, therapeutics, and regenerative medicine. Research institutions are pioneering fundamental discoveries, while industry players translate these breakthroughs into technologies and treatments. This guide examines the key contributors and the practical methodologies underpinning this progress, providing a landscape for professionals navigating careers and collaborations in this dynamic sector. The convergence of advanced optical tools with biological inquiry is creating new paradigms for understanding disease and improving human health [27] [28].

Key Research Institutions

Academic and research institutions are the bedrock of innovation, providing foundational knowledge, training specialized talent, and often pioneering the disruptive technologies that industry later adopts.

Leading Universities in Optics and Optical Sciences

The following institutions are globally recognized for their premier optics and optical sciences programs, which are critical for developing the advanced imaging and sensing technologies used in biomedical applications [29] [30] [31].

Table 1: Top-Tier Global Universities for Optics Research

| Institution | Location | Key Strengths & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Zhejiang University | Hangzhou, China | Leads in global optics research performance [29]. |

| Stanford University | Stanford, California, USA | A top-tier U.S. institution located in Silicon Valley, fostering strong industry ties [29]. |

| University of Arizona | Tucson, Arizona, USA | A leading U.S. program awarding a high volume of degrees; a major hub for optics research [30] [31]. |

| University of Rochester | Rochester, New York, USA | Renowned for its Institute of Optics and strong research output [30] [31]. |

| California Institute of Technology (Caltech) | Pasadena, California, USA | Site of pioneering microrobotics research for targeted drug delivery [27] [29]. |

Table 2: Prominent U.S. Universities in Optical Sciences and Biomedical Engineering

| Institution | Location | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Duke University | Durham, North Carolina, USA | Highly-ranked program focusing on the intersection of engineering and medicine [30] [31]. |

| Ohio State University - Main Campus | Columbus, Ohio, USA | A large, comprehensive research university with strong optics and engineering programs [30] [31]. |

| Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) | Rochester, New York, USA | Offers a practice-oriented program in a region known for optical innovation [30] [31]. |

| University of North Carolina at Charlotte | Charlotte, North Carolina, USA | Shows rapid growth in optics/optical sciences degrees awarded [30]. |

| Columbia University | New York City, New York, USA | BME department hosts pioneering tissue engineering and "organ-on-a-chip" research [32]. |

Institutions at the Forefront of Biomedical Engineering

Beyond optics-specific programs, several broader institutions are leaders in biomedical engineering, often integrating advanced optics into their research.

Columbia University's Department of Biomedical Engineering is a prime example of a hub for translational research. Its Laboratory for Stem Cells and Tissue Engineering, led by Professor Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic, is renowned for groundbreaking work in tissue engineering, bioreactors, and "organ-on-a-chip" technology [32]. The lab's research operates at the intersection of biomaterials, cellular biology, and engineering, requiring close collaboration between biologists and engineers. The environment fosters career growth from research assistant to director of operations, demonstrating a pathway for professional development within a cutting-edge research setting [32].

Case Western Reserve University also offers advanced training and research in biomedical engineering, with a curriculum emphasizing the latest innovations in the field [28].

Key Industry Trends and Innovations

Industry players, from large corporations to agile startups, are leveraging foundational research to develop marketable technologies that address pressing clinical needs. Several key trends highlight the current innovation landscape.

Table 3: Key Innovation Trends in Biomedical Engineering and Optics

| Trend Area | Description | Impact on Healthcare |

|---|---|---|

| Personalized Medicine | AI and genomic sequencing enable therapies tailored to an individual's genetic makeup, lifestyle, and environment [27]. | Improved patient outcomes, fewer side effects, and more targeted therapies [27]. |

| Microrobotics | Microscopic robots capable of delivering drugs directly to targeted areas, such as tumors, with high accuracy [27]. | Reduced systemic drug exposure, minimized side effects, and enhanced efficacy for chronic conditions [27]. |

| AI and Machine Learning | Accelerating drug discovery by analyzing complex datasets from genomics, proteomics, and medical imaging [27] [28]. | Reduced time-to-market for new therapies; earlier and more accurate diagnostics [27]. |

| Advanced Biomaterials & Regenerative Medicine | Using biocompatible materials and 3D bioprinting to create patient-specific implants and tissues [27]. | Addressing donor organ shortages and reducing rejection risks through personalized tissue engineering [27]. |

| Digital Health and Wearables | Devices providing continuous health monitoring and predictive analytics for conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease [27] [28]. | Empowers patients with greater autonomy and provides researchers with longitudinal data [27]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Translating an idea into a validated technology requires rigorous experimental protocols. Below is a detailed methodology for a representative advanced experiment in the field.

Detailed Protocol: Development of a Microrobotic Drug Delivery System

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing and testing microrobots for targeted drug delivery, based on research from institutions like Caltech [27].

Objective: To design, fabricate, and validate the efficacy of biodegradable microrobots for the targeted delivery of a chemotherapeutic agent to a tumor site in vivo.

1. Microrobot Fabrication and Drug Loading

- Materials: Biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLGA), magnetic nanoparticles, chemotherapeutic drug (e.g., Doxorubicin), photolithography setup, micro-emulsion equipment.

- Method: Use a two-step process. First, create a micro-porous scaffold using bioprinting or photolithography. Second, load the scaffold with magnetic nanoparticles for guidance and the chemotherapeutic drug via a micro-emulsion and diffusion process. The surface can be functionalized with targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies) for specific cell binding.

2. In Vitro Validation

- Setup: A micro-fluidic channel mimicking vascular flow is used.

- Guidance Test: Apply an external magnetic field to navigate the microrobots towards a target cell culture (e.g., HeLa cancer cells) within the channel.

- Efficacy Assay: After successful targeting and drug release, use a cell viability assay (e.g., MTT assay) to quantify cancer cell death compared to controls (free drug, non-targeted particles).

3. In Vivo Testing and Imaging

- Animal Model: Use a mouse model with a subcutaneously implanted tumor.

- Administration: Introduce microrobots intravenously.

- Guidance & Imaging: Use MRI to guide the microrobots to the tumor site via a magnetic field. Bio-luminescent or fluorescent imaging tracks the microrobots' location in vivo.

- Efficacy Assessment: Monitor tumor volume over time versus control groups. Post-trial, harvest tumors and major organs for histological analysis (e.g., H&E staining) to confirm targeted drug action and assess off-target effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation relies on a suite of reliable reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for research in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, a key area of biomedical innovation [32] [28].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Tissue Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stem Cells | Foundational cells with the potential to differentiate into various specialized cell types for building tissues. | Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) for bone and cartilage regeneration [28]. |

| Synthetic Biomaterials | Provide the 3D structural scaffold (matrix) that supports cell growth, organization, and tissue development. | Polylactic acid (PLA) or Polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogels for bioprinting [27]. |

| Native Biomaterials | Decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM) from tissues, providing a natural, bioactive scaffold. | Decellularized porcine heart ECM used in developing native biomaterials for repair [32]. |

| Growth Factors | Signaling proteins that direct cell behavior, such as proliferation, migration, and differentiation. | Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP-2) to induce bone formation [28]. |

| Bioreactor Systems | Devices that provide a controlled in vitro environment (e.g., mechanical stimulation, nutrient flow) for tissue growth. | A "organ-on-a-chip" bioreactor that mimics the mechanical and physiological environment of a human organ [32]. |

Visualizing Research Workflows

Effective visualization of complex workflows and relationships is crucial for designing experiments, analyzing data, and communicating findings.

Workflow for Tissue Engineering Experiment

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a standard tissue engineering experiment, from scaffold preparation to analysis [32] [28].

Drug Discovery Signaling Pathway

This diagram visualizes a simplified generic signaling pathway involved in drug discovery for diseases like cancer, showing where therapeutic interventions may target [27] [28].

Biomedical engineering represents a dynamic and rapidly evolving discipline that operates at the intersection of engineering, biology, and medicine. This field focuses on applying engineering principles and problem-solving methodologies to advance healthcare treatment, diagnostic capabilities, and therapeutic interventions [33]. Similarly, optics research has become increasingly integral to biomedical advancement, particularly in the development of sophisticated medical imaging systems, diagnostic equipment, and light-based therapies [34] [35]. The convergence of these domains has created new frontiers in medical science, from advanced microscopy techniques for cellular imaging to optical coherence tomography for non-invasive diagnostics.

The educational pathway for professionals in these interdisciplinary fields requires a robust foundation in both physical and life sciences, coupled with specialized engineering expertise. This guide examines the essential degrees and foundational knowledge required for success at this critical interface, with particular emphasis on the quantitative and technical competencies needed by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in biomedical engineering and optics research.

Essential Degree Pathways

Undergraduate Foundations

The journey toward a career in biomedical engineering typically begins with a bachelor's degree, which provides the fundamental scientific and engineering principles necessary for advanced study or entry-level positions. At leading institutions such as Harvard University, students can pursue several undergraduate pathways, including a Bachelor of Arts (A.B.) in Biomedical Engineering, a Bachelor of Arts in Engineering Sciences with a Biomedical Sciences and Engineering track, or a Bachelor of Science (S.B.) in Engineering Sciences with a Bioengineering track, the latter being an ABET-accredited program [36]. These programs are structured to provide students with a solid foundation in engineering and its application to the life sciences within the context of a liberal arts education [36].

The undergraduate curriculum typically emphasizes:

- Core Engineering Principles: Comprehensive coursework in mathematics, physics, and fundamental engineering concepts [37].

- Biological Sciences: Anatomy, physiology, cellular biology, and genetics to understand the human body and disease processes [37].

- Specialized Biomedical Courses: Biomechanics, biomaterials, bioinstrumentation, and medical imaging [37].

- Hands-on Laboratory Experience: Practical application of theoretical knowledge through laboratory work and design projects [36] [33].

For those interested in the optical aspects of biomedical engineering, relevant coursework includes introduction to optics, fundamental parameters of optical systems, optical specifications, and software design of optical systems [34]. These courses establish the foundational knowledge necessary for understanding how light interacts with biological systems and how optical technologies can be leveraged for medical applications.

Table 1: Undergraduate Course Requirements for Biomedical Engineering Specializations

| Specialization Area | Core Mathematics | Physical Sciences | Engineering Fundamentals | Biological Sciences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General BME | Calculus I-III, Differential Equations, Statistics | Physics I-II, Chemistry, Organic Chemistry | Circuit Analysis, Signals & Systems, Biomechanics | Biology, Physiology, Cell Biology |

| Biomechanics Track | Calculus I-III, Differential Equations, Linear Algebra | Physics I-II, Chemistry | Statics, Dynamics, Materials Science, Fluid Mechanics | Anatomy, Musculoskeletal Biology, Physiology |

| Biomaterials Track | Calculus I-III, Differential Equations | Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Physics | Materials Science, Thermodynamics, Transport Phenomena | Biology, Biochemistry, Cell Biology |

| Bioimaging/Optics Track | Calculus I-III, Differential Equations, Linear Algebra | Physics I-III (Optics), Chemistry | Fourier Analysis, Signal Processing, Introduction to Optics | Biology, Anatomy, Physiology |

Graduate Specialization Opportunities

Graduate education enables deeper specialization in specific subdisciplines of biomedical engineering and optics. Master's and doctoral programs provide advanced training in research methodologies, specialized technical skills, and theoretical frameworks necessary for innovation and leadership in the field [37] [38]. At the graduate level, students can focus on areas such as medical device design, tissue engineering, biomechanics, biomedical imaging, biomaterials, clinical engineering, bioinformatics, or neural engineering [5] [4].

Case Western Reserve University's Master of Science in Biomedical Engineering program exemplifies this approach, offering specialized elective courses in material science, medical imaging, and neural engineering, allowing students to align their education with specific career objectives [38]. Graduate programs also emphasize the development of soft skills, including communication, innovation, creativity, problem-solving, and leadership, which are essential for success in interdisciplinary research environments [38].

Research forms a cornerstone of graduate education in biomedical engineering. At institutions like Harvard, students have access to extensive research opportunities at affiliated institutions such as Harvard Medical School, Boston Children's Hospital, the Wyss Institute, the Broad Institute, and the Rowland Institute [36]. These experiences provide hands-on training with cutting-edge technologies and methodologies, preparing students for research-intensive careers in academia or industry.

Table 2: Graduate Specializations and Career Opportunities in Biomedical Engineering

| Specialization | Advanced Coursework | Research Areas | Potential Career Paths | Industry Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Device Design | Medical Instrumentation, Product Development, Regulatory Science | Surgical Robotics, Wearable Sensors, Point-of-Care Diagnostics | R&D Engineer, Product Design Engineer, Quality Assurance Engineer | High (12% projected growth) [5] |

| Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine | Biomaterials, Cell Biology, Mechanobiology | Artificial Organs, 3D Bioprinting, Stem Cell Therapies | Research Scientist, Bioprocess Engineer, Clinical Trials Manager | High [5] [4] |

| Biomedical Imaging & Optics | Fourier Optics, Photonics, Image Processing | Molecular Imaging, Image-Guided Therapy, Novel Contrast Agents | Imaging Systems Engineer, Clinical Imaging Specialist, Medical Physicist | High [5] [4] |

| Neural Engineering | Neurobiology, Signal Processing, Neural Interfaces | Brain-Computer Interfaces, Neuroprosthetics, Deep Brain Stimulation | Neuroprosthetics Engineer, BCI Developer, Neuroengineering Researcher | Emerging [5] [4] |

| Bioinformatics & Health Data Analytics | Computational Biology, Machine Learning, Statistical Genetics | Genomic Analysis, Predictive Modeling, Precision Medicine | Bioinformatics Analyst, Computational Biologist, Healthcare Data Scientist | High [5] [4] |

Foundational Knowledge Requirements

Core Scientific and Technical Competencies

Success in biomedical engineering and optics research requires mastery of several interconnected knowledge domains. These foundational areas provide the conceptual framework and technical skills necessary for innovation and problem-solving in complex biomedical challenges.

Mathematics and Quantitative Analysis: Biomedical engineering is inherently quantitative, relying on mathematical analysis and modeling to understand systems ranging from subcellular processes to organism-level physiology [36] [39]. Essential mathematical competencies include: