Fluorescence Microscopy in Cell Imaging: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to fluorescence microscopy for cell imaging.

Fluorescence Microscopy in Cell Imaging: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to fluorescence microscopy for cell imaging. It covers fundamental principles and instrumentation, detailed methodological protocols for applications like viability assessment, advanced techniques for troubleshooting and optimizing image quality, and rigorous validation and comparative analysis with methods like flow cytometry. The content addresses critical challenges such as autofluorescence, photobleaching, and scattering, while emphasizing recent advancements and standardized reporting to ensure reproducibility and robust data generation in biomedical research.

Understanding Fluorescence Microscopy: Core Principles and Instrumentation for Cell Imaging

Fluorescence is a form of photoluminescence where a substance absorbs light of a specific wavelength and subsequently emits light of a longer wavelength. This phenomenon was first described in detail by Irish physicist Sir George Gabriel Stokes in 1852, who also coined the term "fluorescence" after the mineral fluorspar [1] [2]. In fluorescence microscopy, this physical principle enables researchers to visualize and study specific cellular components and molecular processes with high specificity and contrast. The fundamental attribute that makes fluorescence so valuable for biological imaging is the Stokes shift—the energy difference between absorbed and emitted photons that allows emission signals to be distinguished from excitation light. Understanding the physical basis of fluorescence is essential for designing rigorous imaging experiments and properly interpreting the resulting data in cell imaging research and drug development.

Fundamental Physical Principles

Electronic Transitions and the Jablonski Diagram

The process of fluorescence can be visualized using a Perrin-Jablonski diagram, which illustrates the electronic and vibrational energy states of a molecule and the transitions between them following photon absorption [1]. When a fluorophore absorbs a photon, promotion from the ground electronic state (S₀) to an excited electronic state (S₁ or S₂) occurs on a femtosecond timescale. This transition is vertical in accordance with the Franck-Condon principle, which states that electronic transitions occur without changes in the position of the atomic nuclei due to their much greater mass compared to electrons [1].

Following excitation, several relaxation processes occur:

- Vibrational relaxation: The molecule rapidly loses excess vibrational energy (10⁻¹² seconds) to its surroundings, relaxing to the lowest vibrational level of S₁.

- Internal conversion: Non-radiative transition between electronic states of the same spin multiplicity.

- Fluorescence emission: The molecule returns to the ground state (10⁻⁹ seconds) by emitting a photon with energy equal to the difference between the excited and ground states.

- Intersystem crossing: Transition to a triplet state (T₁) with subsequent phosphorescence emission may also occur.

The following diagram illustrates these processes:

The Stokes Shift: Fundamental Principles

The Stokes shift, named after George Gabriel Stokes who first documented the phenomenon, refers to the difference in energy or wavelength between the maximum of the first absorption band and the maximum of the fluorescence emission spectrum [1] [3]. Stokes' fundamental observation was that "when the refrangibility of light is changed by dispersion it is always lowered" - meaning fluorescence emission always occurs at longer wavelengths (lower energy) than the excitation light [1].

The Stokes shift arises from several physical processes:

- Vibrational relaxation: Following excitation to higher vibrational levels of S₁, molecules rapidly lose vibrational energy to the environment before emitting fluorescence [1].

- Solvent reorganization: The excited state of a fluorophore typically has a larger dipole moment than the ground state. Polar solvent molecules reorient around the excited dipole, stabilizing the excited state and further lowering its energy [4].

- Configurational changes: The equilibrium geometry of the fluorophore may differ between ground and excited states, contributing to the energy difference [1].

The magnitude of the Stokes shift can be expressed in different units:

- Wavelength: Δλ = λem - λex

- Wavenumber: Δν = (1/λex - 1/λem) × 10⁷ (in cm⁻¹)

- Energy: ΔE = Eex - Eem

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between absorption, emission, and Stokes shift:

Quantitative Analysis of Stokes Shift

Factors Influencing Stokes Shift Magnitude

The magnitude of the Stokes shift is influenced by both the molecular structure of the fluorophore and its environment. Understanding these factors is essential for selecting appropriate fluorophores for specific experimental conditions.

Table 1: Factors Affecting Stokes Shift Magnitude

| Factor | Mechanism | Effect on Stokes Shift |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Polarity | Reorientation of solvent dipole moments around the excited-state fluorophore | More polar solvents typically yield larger Stokes shifts due to greater stabilization of the excited state [1] [4] |

| Fluorophore Structure | Changes in dipole moment between ground and excited states; molecular rigidity | Fluorophores with larger excited-state dipole moments exhibit larger Stokes shifts; rigid structures may restrict conformational changes [3] |

| Temperature | Affects the rate of vibrational relaxation and solvent reorientation dynamics | Higher temperatures can increase Stokes shift slightly due to altered relaxation pathways [4] |

| pH | Alters protonation state of fluorophore, affecting electronic structure | Can significantly change absorption/emission profiles of pH-sensitive fluorophores [5] |

| Molecular Binding | Restriction of fluorophore mobility or changes in local environment | Binding to proteins or membranes often increases quantum yield and may alter Stokes shift [4] |

Representative Stokes Shift Values for Common Fluorophores

The following table provides quantitative Stokes shift data for fluorophores commonly used in biological imaging, demonstrating the range of values encountered in practical applications.

Table 2: Stokes Shift Values of Common Biological Fluorophores

| Fluorophore | Excitation Maximum (nm) | Emission Maximum (nm) | Stokes Shift (nm) | Stokes Shift (cm⁻¹) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAPI | 358 | 461 | 103 | ~6200 | Nuclear staining [2] |

| FITC | 495 | 519 | 24 | ~930 | Antibody conjugation [2] |

| Rhodamine 6G | 525 | 555 | 30 | ~1030 | Counterstaining [1] |

| Alexa Fluor 555 | 555 | 580 | 25 | ~780 | Protein labeling [2] |

| DCM | 480 | 610 | 130 | ~4400 | Specialized applications [1] |

| CY5 | 649 | 670 | 21 | ~480 | Far-red imaging [2] |

| GFP | 395/475 | 509 | 34/34 | ~1800/~1400 | Protein fusion tags [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Fluorescence Microscopy

Protocol: Quantitative Measurement of Stokes Shift in Solution

Objective: Determine the Stokes shift of a fluorophore in various solvent environments.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified fluorophore (e.g., 1 mM stock solution in DMSO)

- Selection of solvents of varying polarity (cyclohexane, ethanol, water)

- Quartz cuvettes (1 cm path length)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer

- pH meter

- Temperature-controlled cuvette holder

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare fluorophore solutions in each solvent at concentrations ensuring absorbance <0.1 at the excitation maximum to avoid inner-filter effects.

- For pH studies, prepare buffers across relevant pH range (e.g., pH 4-9).

- Equilibrate all samples to standard temperature (e.g., 25°C).

Absorption Spectroscopy:

- Record absorption spectra from 250 nm to the red edge of absorption (typically 600-700 nm depending on fluorophore).

- Use matching solvent without fluorophore as blank.

- Identify wavelength of maximum absorption (λ_abs) for each sample.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy:

- Set excitation wavelength to λ_abs for each sample.

- Record emission spectrum from λ_abs to 800 nm (or until signal returns to baseline).

- Use identical instrument settings (slit widths, scan speed, detector voltage) for comparative studies.

- Identify wavelength of maximum emission (λ_em).

Data Analysis:

- Calculate Stokes shift in wavelength: Δλ = λem - λabs

- Convert to wavenumber: Δν = (1/λabs - 1/λem) × 10⁷ cm⁻¹

- Plot Stokes shift values versus solvent polarity parameters (e.g., dielectric constant).

Quality Control:

- Verify absence of Raman scattering peaks by comparing to blank solvent emission.

- Confirm concentration linearity to ensure absence of aggregation effects.

- Replicate measurements (n≥3) to determine experimental error.

Protocol: Live-Cell Fluorescence Imaging with Minimal Phototoxicity

Objective: Acquire high-quality fluorescence images of live cells while maintaining viability for extended time-lapse studies.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cultured cells expressing fluorescent protein or labeled with cell-permeable dye

- #1.5 coverslips (0.17 mm thickness)

- Appropriate live-cell imaging medium

- Environmental chamber controlling temperature, CO₂, and humidity

- Spinning disk confocal or widefield fluorescence microscope

- High-numerical aperture (NA ≥1.4) objective lens

- Sensitive sCMOS or CCD camera

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Plate cells on sterile #1.5 coverslips 24-48 hours before imaging at appropriate density.

- Transfer coverslip to imaging chamber with appropriate medium.

- Allow cells to equilibrate in environmental chamber for at least 30 minutes before imaging.

Microscope Configuration:

- Select appropriate objective lens (60× or 100× high NA recommended for high-resolution imaging) [6].

- Configure filter sets matched to fluorophore excitation/emission spectra.

- Set up hardware-triggered shutters to illuminate samples only during image acquisition [6].

- Adjust camera settings to maximize dynamic range without saturation.

Image Acquisition Optimization:

- Determine minimum excitation intensity that provides acceptable signal-to-noise ratio.

- Use neutral density filters to reduce excitation intensity rather than decreasing exposure time when possible.

- Set spatial sampling according to Shannon-Nyquist criterion (pixel size ≤ resolution limit/2.3) [7].

- For time-lapse imaging, determine maximum acquisition frequency that minimizes photodamage while capturing biological process.

Controls and Validation:

- Include unlabeled control to assess autofluorescence.

- For multi-color imaging, include single-label controls to evaluate bleed-through.

- Monitor cell viability throughout experiment using phase contrast or transmitted light imaging.

- Verify focus stability throughout acquisition period.

Data Collection:

- Acquire z-stacks when necessary, but minimize sections to reduce light exposure.

- Save images in non-proprietary format (e.g., TIFF) with appropriate metadata.

- Document all acquisition parameters for reproducibility.

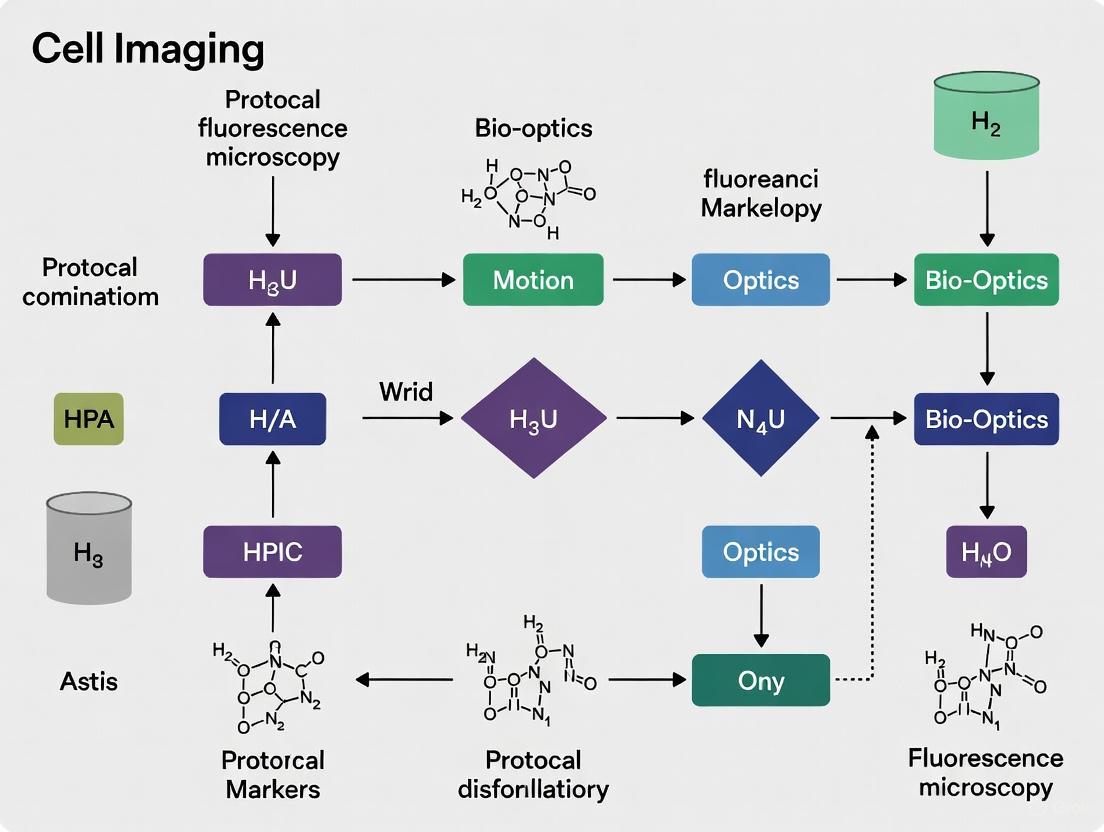

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in configuring a fluorescence microscope for live-cell imaging:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Fluorescence Imaging

| Category | Item | Function/Specification | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorophores | Synthetic dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor series) | High extinction coefficients, good photostability | Preferred for immunostaining; wide range of wavelengths available [8] |

| Fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, mCherry) | Genetically encodable labels | Enable specific protein labeling in live cells; consider maturation time [6] | |

| Immersion Media | Immersion oil (Type F) | Refractive index ~1.518 (23°C) | Standard for oil objectives; match to objective specification [6] |

| Glycerol or water-based immersion | Lower refractive index | For specialized water- or glycerol-immersion objectives [6] | |

| Sample Mounting | #1.5 Coverslips | 0.17 mm thickness | Standard thickness for most high-NA objectives [7] |

| Live-cell imaging chambers | With environmental control | Maintain temperature, CO₂, humidity for live cells [6] | |

| Mounting Media | Antifade reagents (e.g., p-phenylenediamine) | Reduce photobleaching | Essential for fixed samples; specific formulations for different fluorophores [7] |

| Live-cell compatible media | HEPES-buffered, no phenol red | Minimize background fluorescence while maintaining viability [7] | |

| Calibration Tools | Fluorescent beads (various sizes) | Point sources for resolution measurement | Validate system performance; assess point spread function [7] |

| Tetraspeck beads | Multiple emission wavelengths | Verify channel registration in multi-color imaging [7] |

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Environmental Sensitivity and Biosensing

The Stokes shift provides a sensitive reporter of local environment that can be exploited for biosensing applications. As shown in Figure 3, the emission maximum of environment-sensitive fluorophores can shift dramatically with changes in solvent polarity [4]. This principle underlies numerous fluorescence-based sensors:

- Membrane order probes: Laurdan and similar dyes exhibit large Stokes shift changes in different lipid environments

- Ion sensors: Fluorophores coupled to ion chelators show emission shifts upon binding

- Molecular rotors: Fluorophores whose quantum yield depends on viscous drag can report on local viscosity

Implications for Microscope Design and Filter Selection

The Stokes shift directly influences the design and configuration of fluorescence microscopes. Key considerations include:

Filter selection: Sufficient separation between excitation and emission maxima enables effective spectral separation [2]. Fluorophores with small Stokes shifts require more precise filter sets to avoid excitation light contamination.

Detector sensitivity: The emission wavelength determines detector selection, with CCD and sCMOS cameras offering optimal performance in different spectral regions [6].

Objective transmission: Both excitation and emission wavelengths must fall within the high-transmission range of the objective lens, which can be problematic for UV-excited fluorophores [6].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between fluorophore spectra and microscope filter configuration:

Anti-Stokes Shift and Upconversion

While less common in biological imaging, anti-Stokes shifts—where emission occurs at shorter wavelengths than excitation—can occur through several mechanisms [1] [3]:

- Thermal energy contribution: Molecules in excited vibrational states can absorb photons, resulting in emission at higher energy

- Multiphoton processes: Simultaneous absorption of multiple lower-energy photons

- Photon upconversion: Specialized materials (e.g., lanthanide-doped nanoparticles) that can sequentially absorb multiple photons

These principles enable techniques such as anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy and upconversion microscopy, which can reduce background autofluorescence in complex biological samples.

Fluorescence microscopy is an indispensable tool in modern biological and biomedical research, enabling the visualization of specific cellular components and dynamic processes with high specificity and contrast [9]. The technique relies on the principle of fluorescence, where certain molecules called fluorophores absorb high-energy (shorter wavelength) light and subsequently emit lower-energy (longer wavelength) light [2]. This property allows researchers to target and image specific structures within cells against a dark background, providing exceptional detection sensitivity down to the single-molecule level [2].

The development of fluorescence microscopy has revolutionized cellular research, particularly with the introduction of fluorescently labeled antibodies in the 1940s, which enabled molecular-specific imaging of cells and subcellular structures [9]. Today, fluorescence microscopy techniques are essential for analyzing protein-protein interactions, studying biomolecular interactions, and making stoichiometric measurements at the molecular level [9].

This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the essential components of a fluorescence microscope system, with particular emphasis on their roles in live-cell imaging applications. Proper configuration and understanding of these components are critical for obtaining high-quality, quantitative data while maintaining cell viability during imaging experiments [6].

Core Optical Components

The illumination system is fundamental to fluorescence microscopy, providing the specific wavelengths required to excite fluorophores within the specimen. Modern fluorescence microscopes employ various light sources, each with distinct characteristics and applications.

Table 1: Common Light Sources in Fluorescence Microscopy

| Light Source Type | Spectral Characteristics | Output Power | Applications | Advantages and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury Arc Lamps | Broad spectrum from UV to visible | High intensity | Widefield fluorescence; multiple fluorophore excitation | High brightness; limited lifespan; generates heat |

| Xenon Arc Lamps | Relatively uniform spectrum | High intensity | Quantitative measurements; ratio imaging | More stable output than mercury; limited UV output |

| LEDs | Narrow emission bands (discrete wavelengths) | Adjustable, moderate intensity | Widefield and some confocal systems; live-cell imaging | Long lifespan; instant on/off; minimal heat; customizable |

| Lasers | Single, intense wavelengths | Very high intensity | Confocal, multiphoton, TIRF microscopy | High brightness for dim samples; can cause photodamage |

For live-cell imaging, controlling light exposure is paramount to minimize phototoxicity and photobleaching [6]. LED-based light sources have become increasingly popular due to their rapid switching capabilities, which eliminate the need for mechanical shutters and enable precise control of exposure [6]. Proper adjustment of the illumination system using Köhler illumination ensures even distribution of light across the entire field of view, providing optimal image quality [10] [11].

Objective Lenses

The objective lens is arguably the most critical component influencing image quality in fluorescence microscopy. Objectives are characterized by their magnification, numerical aperture (NA), and degree of optical correction.

Numerical aperture determines both the light-gathering ability and resolving power of the objective. Higher NA objectives collect more emitted fluorescence light, resulting in brighter images and improved resolution [6]. For live-cell imaging, the choice of objective involves balancing magnification, NA, and working distance. While lower magnifications reduce specimen irradiance, sufficient sampling of the microscope's optical resolution often requires high-magnification (e.g., 100×) objectives [6].

Modern high-performance objectives for fluorescence applications include apochromats, which provide chromatic correction for three colors, and are often designed with special coatings to maximize transmission across a broad wavelength range [6].

Filter Cubes

Filter cubes are essential for separating the intense excitation light from the weaker emitted fluorescence. A standard filter cube consists of three components: an excitation filter, a dichroic mirror (or beamsplitter), and an emission filter [12] [13].

Excitation Filter: This component is positioned between the light source and the specimen. It selectively transmits only the specific wavelengths required to excite the target fluorophore while blocking other wavelengths [12] [13]. Excitation filters are typically bandpass filters, allowing a narrow range of wavelengths to pass through.

Dichroic Mirror: Mounted at a 45-degree angle within the filter cube, the dichroic mirror reflects the shorter-wavelength excitation light toward the specimen while transmitting the longer-wavelength emitted fluorescence to the detector [12] [2]. This specialized interference filter efficiently separates the excitation and emission pathways.

Emission Filter: Positioned after the dichroic mirror and before the detector, the emission filter (also called a barrier filter) blocks any residual excitation light that may be scattered by the specimen or optical components, while allowing the desired fluorescence emission to pass through to the detector [12] [2].

The selection of appropriate filter cubes must be matched to the spectral properties of the fluorophores used in the experiment. Modern microscopes often accommodate multiple filter cubes on a revolving turret, allowing rapid switching between different fluorescence channels during multi-color imaging experiments [2].

Detection Systems

The detection system captures the weak fluorescence emission signals and converts them into measurable electronic signals. The choice of detector significantly impacts sensitivity, spatial resolution, and temporal resolution in fluorescence imaging.

Cooled scientific-grade cameras with low readout noise are essential for detecting dim fluorescent signals in live-cell imaging [6]. The main camera types used in fluorescence microscopy include:

- CCD (Charge-Coupled Device) Cameras: Known for high quantum efficiency and low noise, interline CCD cameras have historically shown excellent performance for live-cell imaging [6].

- EM-CCD (Electron-Multiplying CCD) Cameras: These cameras provide additional amplification of the signal before readout, making them suitable for low-light applications such as single-molecule imaging [6].

- sCMOS (Scientific Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor) Cameras: Modern sCMOS cameras offer high speed, large field of view, and good quantum efficiency with lower cost than EM-CCDs [6].

For laser scanning confocal microscopy, photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) are typically used as detectors. These devices scan the specimen point-by-point, offering high sensitivity but slower acquisition speeds compared to area detectors like CCD and sCMOS cameras [9].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Typical Irradiance Values in Fluorescence Microscopy

| Microscopy Modality | Typical Irradiance at Specimen | Comparison to Sunlight | Implications for Live-Cell Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spinning Disk Confocal | ~100 W/cm² at 100× magnification | ~1000× total solar irradiance | Lower photodamage; suitable for extended timelapse |

| Laser Scanning Confocal | Several orders of magnitude higher than spinning disk | >10,000× total solar irradiance | Higher risk of phototoxicity and photobleaching |

| Widefield Epifluorescence | Similar to spinning disk (depends on source) | ~100-1000× total solar irradiance | Good for live cells with proper exposure control |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | High peak power, but low average power | N/A | Reduced photobleaching in focal volume; deeper tissue penetration |

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in fluorescence microscopy is influenced by multiple factors, including fluorophore brightness, camera noise, and background fluorescence. To maximize SNR while minimizing photodamage, researchers should:

- Use the lowest light intensity that provides acceptable image quality

- Optimize camera exposure settings and consider binning for dim samples

- Select appropriate filters matched to the fluorophore spectra

- Use the lowest magnification objective that provides the required resolution

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Fluorescence Microscopy

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Notes on Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Proteins | GFP, RFP, YFP, and derivatives (eGFP, pHluorin) [9] | Protein labeling and localization in live cells | Genetically encoded; enable tracking of protein expression and dynamics |

| Synthetic Dyes | Alexa Fluor series, Hoechst 33258, DAPI [9] | Staining fixed cells or specific cellular structures | Often brighter and more photostable than fluorescent proteins |

| Immunofluorescence Reagents | Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies | Specific antigen detection in fixed cells | High specificity; requires cell fixation and permeabilization |

| Live Cell Stains | FM dyes, MitoTracker, CellMask | Staining membranes, organelles, or whole cells in live specimens | Variable toxicity; requires concentration optimization |

| Environment-Sensitive Probes | Fura-2, BCECF, Fluo-4 | Measuring ion concentrations (Ca²⁺, pH) | Require calibration for quantitative measurements |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Microscope Setup for Quantitative Live-Cell Fluorescence Imaging

Principle: Proper configuration of the fluorescence microscope is essential for obtaining quantitative data while maintaining cell viability during live-cell imaging experiments.

Materials:

- Inverted fluorescence microscope with Köhler illumination capability

- Temperature and CO₂ incubation system for live cells

- High-numerical aperture objective (e.g., 60× or 100× oil immersion)

- Appropriate filter sets matched to fluorophores

- Cooled CCD or sCMOS camera

Procedure:

Microscope Alignment and Köhler Illumination [10]:

- Turn on the light source and focus on a representative sample

- Close the field diaphragm until its edges are visible in the field of view

- Adjust the condenser height until the edges of the diaphragm are in sharp focus

- Center the condenser using the adjustment screws so the diaphragm image is centered

- Open the field diaphragm until its image just disappears from the field of view

Optimization of Illumination Intensity [6]:

- Use neutral density filters or LED power control to reduce excitation intensity to the minimum level that provides acceptable SNR

- Implement hardware-triggered shutters to ensure illumination is only present during image acquisition

- For multi-color imaging, ensure proper alignment of all fluorescence channels

Camera Configuration:

- Set camera to its lowest readout noise setting

- Adjust exposure time to avoid pixel saturation while maximizing dynamic range

- For dim samples, consider 2×2 binning to improve SNR at the expense of resolution

Environmental Control:

- Pre-equilibrate the incubation system to maintain 37°C and 5% CO₂

- Allow the objective to reach temperature equilibrium to prevent focus drift

Troubleshooting:

- If image contrast is poor, verify proper setting of the condenser aperture diaphragm (typically 70-80% of objective NA)

- If focus drifts during time-lapse imaging, ensure adequate temperature stabilization of the objective

- If photobleaching is excessive, further reduce illumination intensity and increase camera exposure time instead

Protocol: Multi-color Live-Cell Imaging with Multiple Fluorophores

Principle: Imaging multiple cellular components simultaneously requires careful selection of fluorophores with minimal spectral overlap and appropriate filter sets.

Materials:

- Cells expressing fluorescent protein fusions or labeled with fluorescent dyes

- Microscope with multiple filter cubes or multiband filter sets

- Software for spectral unmixing (if significant bleed-through occurs)

Procedure:

Fluorophore Selection:

- Choose fluorophores with well-separated excitation and emission spectra

- Consider large Stokes shift fluorophores to facilitate separation of excitation and emission

- Verify that all fluorophores are compatible with the available laser lines or illumination sources

Filter Selection [12]:

- Select excitation filters that match the peak excitation of each fluorophore

- Choose emission filters that capture the emission peak while blocking other fluorophores

- Ensure dichroic mirrors have transition wavelengths between the excitation and emission bands of each fluorophore

Control Experiments:

- Image each fluorophore individually to verify specific signal detection

- Prepare samples with single labels to measure and correct for bleed-through between channels

- Include unstained controls to assess autofluorescence levels

Sequential Imaging:

- When significant spectral overlap exists, acquire images sequentially rather than simultaneously

- Minimize time between channel acquisitions to reduce temporal discrepancies

- Use software-based unmixing algorithms to separate overlapping signals when necessary

Troubleshooting:

- If bleed-through is observed between channels, narrow the emission filters or use sequential acquisition

- If signal is weak in one channel, verify that the excitation filter matches the fluorophore's excitation spectrum

- If colocalization appears artifactual, verify channel alignment using multicolor fluorescent beads

System Diagrams and Workflows

Fluorescence Filter Cube Light Path

Live-Cell Imaging Optimization Workflow

The performance of a fluorescence microscope in cell imaging research depends critically on the proper selection, configuration, and integration of its core components: light sources, objective lenses, filter cubes, and detection systems. For live-cell imaging applications, additional considerations must be made to balance signal-to-noise ratio against phototoxicity and photobleaching.

Understanding the principles behind each component allows researchers to optimize their imaging systems for specific applications, whether for high-speed dynamics, super-resolution imaging, or long-term observation of delicate biological processes. The protocols provided here offer a foundation for setting up a fluorescence microscope for quantitative live-cell imaging, with an emphasis on maintaining cell viability while obtaining high-quality data.

As fluorescence microscopy continues to evolve, with new technologies such as light-sheet microscopy and improved detector systems becoming more accessible, the fundamental principles outlined in this application note will remain relevant for maximizing the effectiveness of these advanced imaging platforms.

Choosing Fluorophores and Fluorescent Proteins for Cellular Targets

The selection of appropriate fluorophores and fluorescent proteins is a critical step in the design of robust and reliable fluorescence microscopy experiments. The correct choice directly influences signal strength, resolution, and the accuracy of biological interpretation. For researchers and drug development professionals, this process extends beyond simple color selection; it requires a systematic consideration of the experimental platform, the cellular target, and the photophysical properties of the labels. This application note provides a structured guide and detailed protocols to inform these decisions, ensuring high-quality cellular imaging data.

Fundamental Principles of Fluorophore Selection

The core principle of fluorescence involves the absorption of high-energy light (excitation) by a fluorophore and the subsequent emission of lower-energy light. Several key concepts guide the selection process:

- Stokes Shift: The difference between the peak excitation and peak emission wavelengths. A larger Stokes shift simplifies the separation of the emission signal from scattered excitation light, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio [14].

- Quantum Yield: The efficiency with which a fluorophore converts absorbed photons into emitted photons. A higher quantum yield results in a brighter signal [14].

- Extinction Coefficient: A measure of how strongly a fluorophore absorbs light at a specific wavelength. A fluorophore with a high extinction coefficient absorbs light more efficiently, which also contributes to brightness [15].

The interplay of these factors determines a fluorophore's overall brightness, which is crucial for detecting low-abundance targets. Furthermore, photostability—a fluorophore's resistance to irreversible bleaching upon repeated illumination—is vital for experiments involving time-lapse imaging or prolonged super-resolution data acquisition [14] [16].

A Systematic Guide to Fluorophore and Fluorescent Protein Selection

Selecting the optimal fluorescent tag requires matching its properties to the experimental needs. The decision flow below outlines the primary considerations, from choosing a labeling strategy to final validation.

Choosing a Labeling Strategy

The experimental question dictates the choice of labeling strategy, each with distinct advantages and applications.

- Fluorescent Proteins (FPs): Genetically encoded tags like Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP) are ideal for live-cell imaging, enabling the tracking of protein localization and dynamics in real time. Popular pairs for FRET studies include CFP (donor) and YFP (acceptor) [17]. However, FPs can be less bright and photostable than synthetic dyes.

- Self-Labeling Protein Tags (SLPs): Systems such as SNAP-tag, HaloTag, and CLIP-tag offer a hybrid approach. The protein of interest is genetically fused to the tag, which then covalently binds to a cell-permeable synthetic fluorophore. This combines genetic targeting with the superior brightness and photostability of organic dyes [15] [16]. Recent advances, like SNAP-tag2, offer 100-fold faster labeling kinetics and a fivefold increase in fluorescence brightness with optimized rhodamine substrates [15].

- Immunofluorescence: For fixed-cell imaging, immunofluorescence using antibody-fluorophore conjugates (e.g., Alexa Fluor dyes) is the gold standard for labeling endogenous proteins. While it offers high specificity, the large size of antibodies can limit access to densely packed targets [16].

Quantitative Comparison of Common Fluorophores

The following tables summarize key properties of widely used fluorophores to aid in selection.

Table 1: Properties of Common Organic Dyes and Quantum Dots

| Fluorophore | Excitation (nm) | Emission (nm) | Chemical Property | Primary Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 350 | 343 | 441 | Small organic dye | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| Alexa Fluor 488 | 499 | 520 | Small organic dye | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| Alexa Fluor 555 | 553 | 568 | Small organic dye | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| Alexa Fluor 594 | 590 | 618 | Small organic dye | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| Cy3 | 554 | 566 | Small organic dye | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| FITC | 498 | 517 | Small organic dye | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| TMR (Tetramethylrhodamine) | 552 | 578 | Small organic dye | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| Qdot 605 | 300 | 603 | Quantum Dot | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| BODIPY FL | 502 | 511 | Small organic dye | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

Table 2: Properties of Common Fluorescent Proteins and Advanced Tags

| Fluorophore/Tag | Excitation (nm) | Emission (nm) | Type / Property | Primary Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFP | 488 | 510 | Fluorescent Protein | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| RFP | 555 | 584 | Fluorescent Protein | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| CFP | 435 | 485 | Fluorescent Protein | Microscopy, Flow Cytometry [18] |

| SNAP-tag2 | N/A | N/A | Self-Labeling Tag | Live-cell super-resolution [15] |

| FLEXTAG | N/A | N/A | Small, Self-Renewable Tag | Multi-color nanoscopy [16] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Live-Cell Labeling with SNAP-tag2

SNAP-tag2 represents a significant advancement for live-cell imaging, offering faster labeling and brighter signals [15].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Plasmid: SNAP-tag2 vector fused to your protein of interest.

- Cell Line: Mammalian cells suitable for transfection (e.g., HEK293, HeLa).

- Substrate: TF–TMR or other TF–(fluorophore) conjugate (e.g., 100-500 nM working concentration).

- Imaging Medium: FluoroBrite DMEM or CO₂-independent medium, without phenol red.

Methodology:

- Transfection: Transfect cells with the SNAP-tag2 construct using a standard method (e.g., lipofection) and culture for 24-48 hours to allow for protein expression.

- Preparation: Pre-warm imaging medium to 37°C.

- Labeling:

- Replace the culture medium with fresh, pre-warm imaging medium.

- Add the TF-fluorophore substrate directly to the medium at the recommended final concentration (e.g., 100 nM). Gently swirl the plate to mix.

- Incubate the cells for 5-15 minutes at 37°C. The fast kinetics of SNAP-tag2 significantly reduces the required labeling time.

- Washing: Carefully remove the labeling medium and wash the cells 2-3 times with a generous volume of pre-warm imaging medium to remove unbound dye.

- Imaging: Add fresh imaging medium and proceed with live-cell imaging. The high brightness and fluorogenicity of the system provide a strong signal with low background.

Protocol: Intensity-based Live-Cell FRET Imaging

FRET is a powerful technique for studying protein-protein interactions. This protocol uses CFP and YFP as an example pair [17].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Plasmids: Donor (CFP-fusion) and acceptor (YFP-fusion) constructs.

- Cell Line: Appropriate mammalian cell line.

- Microscope: System capable of sensitive, fast multichannel imaging and equipped with CFP/YFP filter sets.

Methodology:

- Specimen Preparation: Co-transfect cells with the donor and acceptor constructs. Include controls: donor-only and acceptor-only cells.

- Image Acquisition: For each field of view, acquire three images using specific filter sets:

- Donor Channel: CFP excitation/CFP emission.

- Acceptor Channel: YFP excitation/YFP emission.

- FRET Channel: CFP excitation/YFP emission.

- Calibration & Image Processing:

- Background Subtraction: Subtract background intensity from all images.

- Spectral Crosstalk Correction: Use donor-only cells to measure the fraction of donor bleed-through into the FRET channel. Use acceptor-only cells to measure the fraction of direct acceptor excitation by the donor excitation light.

- FRET Calculation: Calculate the corrected FRET signal using the formula:

Corrected FRET = I_FRET - (a * I_Donor) - (b * I_Acceptor), whereaandbare the crosstalk coefficients determined from the controls. - FRET Efficiency: The corrected FRET signal can be normalized to the donor signal (or acceptor signal) to calculate FRET efficiency, providing a quantitative measure of interaction.

The workflow for a typical FRET experiment, from setup to quantitative analysis, is outlined below.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

Achieving high-quality images requires careful optimization of both the sample and the microscope.

- Microscope Setup: Use objectives with high numerical aperture (NA), as image intensity in reflected light fluorescence scales with the fourth power of the objective's NA [19]. Ensure the light source is properly aligned and that filter sets are matched to the fluorophores.

- Image Acquisition: To maximize the signal-to-noise ratio, start with the gentlest excitation light and increase the exposure time until the signal is clear above the background. Only increase the light intensity if the exposure time becomes impractically long, to minimize photobleaching and phototoxicity [20]. Always check the histogram to ensure the signal is not saturated [21] [20].

- Sample Preparation: For fixed samples, thorough washing is critical to remove unbound fluorophore and reduce background autofluorescence [19]. For self-labeling tags, new fixation methods are being developed to overcome crosslinking-induced reductions in labeling efficiency [16].

- Troubleshooting Common Issues:

- High Background: Increase washing stringency post-labeling. Optimulate blocker if using antibodies.

- No Signal: Verify fluorophore activity, substrate concentration, and filter set configuration.

- Photobleaching: Reduce illumination intensity and exposure time. Use an anti-fading mounting medium for fixed samples or consider self-renewable tags like FLEXTAG for live-cell applications [16].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Emerging technologies are pushing the boundaries of fluorescence imaging. Self-renewable protein tags, such as the FLEXTAG system, allow continuous exchange of fluorophores during imaging, which virtually eliminates photobleaching and enables unprecedented durations of super-resolution imaging in both live and fixed cells [16]. Furthermore, the engineering of tags with dramatically improved kinetics and brightness, like SNAP-tag2, is enhancing our ability to track fast cellular dynamics with high clarity [15]. These advances, combined with improved chemical blocking and fixation protocols, are paving the way for more reliable and accessible multi-color nanoscopy.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| SNAP-tag2 / HaloTag | Self-labeling protein tags for covalently attaching bright, synthetic fluorophores to proteins of interest in live cells. [15] |

| Alexa Fluor Dyes | A family of bright, photostable synthetic dyes commonly conjugated to antibodies for immunofluorescence or to substrates for self-labeling tags. [18] |

| Qdot Probes | Semiconductor quantum dots offering extreme brightness and narrow emission peaks, ideal for multiplexed imaging. [18] |

| FLEXTAG System | A set of small, self-renewable tags for anti-fading, multi-color super-resolution imaging across various modalities (STED, STORM, PAINT). [16] |

| CFP/YFP FRET Pair | A classic pair of fluorescent proteins used in Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) experiments to study protein-protein interactions. [17] |

Fluorescence microscopy is a cornerstone of modern plant research, enabling the visualization of subcellular structures, protein localization, and dynamic biological processes. However, plant specimens present unique challenges that can significantly compromise image quality and data interpretation. The presence of light-scattering cell walls, waxy cuticles, and broad-spectrum autofluorescence creates formidable barriers for researchers [22] [23]. These inherent properties often lead to poor signal-to-noise ratios, hampered probe penetration, and difficulties in distinguishing specific labels from background noise [24]. This Application Note details standardized protocols and advanced reagents designed specifically to overcome these obstacles, thereby enhancing the reproducibility, quality, and informational yield of fluorescence imaging in plant systems.

Addressing Key Challenges: Protocols and Reagents

Managing Autofluorescence

Plant tissues exhibit strong autofluorescence, primarily from chlorophyll, phenols, and cell wall components like lignin, which can overlap with the emission spectra of common fluorescent probes [23]. The following table summarizes the sources and strategies for managing autofluorescence:

Table 1: Common Sources of Autofluorescence in Plant Tissues and Mitigation Strategies

| Source | Emission Range | Affected Tissues | Imaging Strategies | Sample Preparation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll | ~650-680 nm (Red) | Leaves, green stems | Use far-red probes; Spectral unmixing [23] | Chemical clearing (e.g., ClearSee) [24] |

| Cell Walls (Lignin) | ~450-500 nm (Blue-Green) | Vascular, supportive tissues | Choose probes with distinct spectra (e.g., red fluorescent proteins) [23] | Photobleaching protocol [25] |

| Phenols | Broad Spectrum | Various, especially in fixed tissues | Linear separation of signals [23] | Reducing agents in fixatives [23] |

For persistent autofluorescence, a targeted photobleaching protocol can be highly effective. The following workflow is adapted from a method developed for microglia but is applicable to plant tissues [25].

Protocol 2.1: Photobleaching for Autofluorescence Reduction

- Sample Preparation: Perform free-floating immunofluorescent staining on your plant tissue sections.

- PBS Rinse: Wash the stained samples in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove excess reagents.

- Photobleaching Setup: Mount the sample in an antifade mounting medium on a glass slide. Seal the coverslip.

- Light Exposure: Expose the entire sample to broad-spectrum light from a fluorescence microscope lamp or a dedicated high-power LED source for 30-60 minutes.

- Post-Treatment Imaging: Following photobleaching, acquire fluorescence images. A significant reduction in autofluorescence signal should be observed, improving the specific signal-to-noise ratio.

Advanced microscopy techniques like Simultaneous Label-free Autofluorescence Multi-Harmonic (SLAM) microscopy can also be employed. This nonlinear optical method leverages endogenous signals without exogenous labels, using multiphoton-excited autofluorescence and harmonic generation to provide complementary contrast and metabolic information, thus turning a challenge into a source of information [26].

Overcoming the Waxy Cuticle Barrier

The plant cuticle, a waxy layer on the aerial surfaces, acts as a formidable barrier to the infiltration of aqueous solutions and large molecular weight probes [22] [27]. A novel laser-based method offers a precise and non-invasive solution.

Protocol 2.2: Selective Wax Cuticle Ablation for Enhanced Foliar Uptake

This protocol uses a 532 nm Nd:YAG laser to selectively remove the wax cuticle, significantly improving the penetration of agrochemicals and fluorescent probes without damaging the underlying epidermis [27].

- Laser Calibration: Set up a 532 nm Nd:YAG laser system. Adjust the pulse duration and fluence to establish an energy density window that ablates the wax but is reflected by the underlying epidermis.

- Leaf Treatment: Irradiate target areas on the leaf surface (e.g., in a 1 cm-diameter region using single-pulse laser shots). This can expose up to 80% of the underlying epidermis within the irradiated footprint.

- Application: Immediately apply the desired aqueous solution, such as a fluorescent probe (e.g., 2-NBDG) or Zn-based foliar fertilizer, to the treated area.

- Validation: Efficacy can be confirmed by tracking the radial expansion velocity of the fluorescent probe or using Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) to quantify elemental uptake. This method has been shown to improve uptake by over 11,000% compared to untreated controls [27].

Diagram 1: Selective Wax Ablation Workflow.

Probing the Dynamic Cell Wall

The plant cell wall is a dynamic and complex structure, but its study has been hindered by the limitations of existing probes, many of which require fixation or lack functional imaging capabilities [28]. The CarboTag toolbox represents a significant advancement for live functional imaging of cell walls.

Protocol 2.3: Live Functional Imaging of Cell Walls with CarboTag

CarboTag is a modular synthetic motif based on a pyridine boronic acid that directs cargo to the cell wall via dynamic covalent bonding with diols in cell wall carbohydrates [28].

- Probe Selection: Select an azide-functionalized fluorophore (e.g., AlexaFluor488, sulfo-Cy3, sulfo-Cy5) or functional reporter (for pH, ROS, porosity) from the commercially available range.

- Conjugation: Conjugate the selected azide-cargo to the alkyne-bearing CarboTag motif using click chemistry. The resulting probe is water-soluble and minimally toxic.

- Staining: Incubate live plant samples (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings) in a solution containing the CarboTag probe for 30-60 minutes.

- Imaging: Rinse samples and image using confocal or super-resolution microscopy. CarboTag provides rapid tissue penetration, exclusive cell wall staining (no membrane insertion), and is compatible with a wide diversity of plant species, from green algae to ferns [28].

A groundbreaking study from Rutgers University successfully visualized cellulose biosynthesis in real-time by combining a custom bacterial cellulose-binding probe with Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. This protocol used protoplasts (cells with walls removed) to create a "blank slate," enabling the clear visualization of new cellulose fibrils being synthesized and self-assembling into a network over 24 hours [29] [30].

Diagram 2: CarboTag Cell Wall Imaging.

Table 2: Comparison of Cell Wall Imaging Probes

| Probe Name | Type | Target / Mechanism | Key Advantages | Live Cell Compatible? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarboTag [28] | Chemical | Diols in carbohydrates via boronic acid | Modular, rapid penetration, multiplexable, functional reporters (pH, ROS) | Yes |

| Calcofluor White (CFW) [28] | Chemical | Polysaccharides (e.g., β-glucans) | Well-established, inexpensive | Yes (but shows cytotoxicity) |

| Renaissance SR2200 [28] | Chemical | Cellulose | Bright staining | Yes (but slow penetration) |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) [28] | Chemical | Pectin/compromised cells | Nucleic acid stain, enters dead cells | Limited (toxic, internalizes) |

| Bacterial Cellulose-Binding Probe [29] | Protein-based | Crystalline cellulose | Highly specific, used for biosynthesis tracking | Yes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents and tools discussed in this note for addressing plant-specific imaging challenges.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Plant Fluorescence Imaging

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Features | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CarboTag Motif [28] | Modular cell wall targeting group | Directs cargo to cell wall; enables live, functional imaging | Conjugated to dyes for multiplexed cell wall staining. |

| Selective Wax Ablation Laser (532 nm Nd:YAG) [27] | Non-invasive removal of leaf cuticle | Enhances foliar uptake of probes/agrochemicals by >11,000% | Preparing leaf surfaces for efficient infiltration of solutions. |

| ClearSee [24] | Chemical clearing agent | Reduces light scattering and autofluorescence in whole tissues | Clearing plant organs for deep-tissue 3D imaging. |

| AlexaFluor488 Azide [28] | Fluorophore for conjugation | Bright, photostable green fluorescent dye | Creating CarboTag-AF488 for cell wall visualization. |

| 2-NBDG [27] | Fluorescent glucose analog | Tracks uptake and transport of sugars | Validating efficacy of cuticle ablation. |

| Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) Microscope [29] | High-resolution surface imaging | Minimally invasive, ideal for tracking surface dynamics | Imaging cellulose biosynthesis on the surface of protoplasts. |

The Critical Role of Objective Lenses and Immersion Oils in Image Resolution

In fluorescence microscopy, the pursuit of high-resolution imagery is paramount for elucidating subcellular structures and dynamic processes. The objective lens and immersion oil form a critical optical partnership that directly determines the resolution and clarity of acquired images. This relationship is governed by fundamental physical principles, primarily the numerical aperture (NA), which defines the light-gathering ability and resolving power of the microscope system. Proper selection and application of immersion oils are not merely procedural steps but are essential for achieving theoretical performance limits in both conventional and super-resolution microscopy platforms. This application note provides detailed protocols and quantitative guidance to empower researchers to optimize these crucial components for advanced cell imaging research.

Fundamental Principles of Resolution Enhancement

The theoretical foundation of resolution enhancement through immersion oils lies in managing light refraction at the interface between the microscope slide, the immersion medium, and the objective lens. When light passes through media with different refractive indices, it bends according to Snell's Law, causing spherical aberration and signal loss that degrade image quality.

Immersion oil possesses a refractive index (typically ~1.515) closely matched to that of glass slides and coverslips (~1.52). By placing a drop of immersion oil between the slide and the objective lens, it creates a continuous optical path that effectively minimizes light refraction at these interfaces [31]. This allows more light rays, including higher-order diffracted rays carrying fine specimen detail, to enter the objective lens.

The numerical aperture (NA) quantifies this light-gathering ability and is defined by the equation: NA = n × sin(θ), where 'n' is the refractive index of the immersion medium and 'θ' is the half-angle of the cone of light collected by the objective. Without immersion oil (air: n ≈ 1.0), the maximum practical NA is limited to approximately 0.95. With immersion oil (n ≈ 1.515), the NA can reach 1.4 or higher, significantly increasing both resolution and signal collection efficiency [31] [32].

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental principle and its practical workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions: Immersion Oils and Calibration Materials

Successful high-resolution imaging requires both proper selection of immersion oils and standardized materials for system calibration. The following table details key reagents essential for optimizing and validating microscope performance.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for High-Resolution Fluorescence Microscopy

| Reagent Category | Specific Types | Key Applications | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immersion Oils | Type A (Low Viscosity) | Routine microscopy, quick procedures | Easy application and cleaning; ideal for frequent objective changes [31] |

| Type B (High Viscosity) | Long-term imaging, z-stack acquisition | Stable refractive index; minimizes need for reapplication [31] | |

| Type NVH (Non-Volatile) | Prolonged observation sessions | Very slow evaporation rate; maintains stability for hours [31] | |

| Fluorescent Grade | Fluorescence microscopy applications | Minimizes background autofluorescence; enhances contrast [31] | |

| Calibration Materials | TetraSpeck Microspheres (100 nm) | PSF measurement, resolution validation | Smaller than system PSF; determines resolution limits [32] |

| TetraSpeck Microspheres (500 nm) | Size measurement accuracy, chromatic aberration | Larger than PSF; validates quantification accuracy [32] |

Quantitative Performance Data

The theoretical and practical performance of an imaging system is characterized by specific quantitative metrics. Calibration using standardized materials provides critical data on resolution limits, ensuring accurate interpretation of biological images.

Table 2: Theoretical Resolution Limits and Calibration Standards

| Microscopy Modality | Theoretical Lateral Resolution | Theoretical Axial Resolution | Calibration Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Widefield Epifluorescence | ~250 nm [32] | ~600 nm [32] | TetraSpeck Beads (100 nm, 500 nm) [32] |

| Laser Scanning Confocal (LSCM) | ~250 nm [23] | ~600 nm [23] | Fluorescent beads for PSF measurement [32] |

| Structured Illumination (SIM) | 90-130 nm [33] | 250-400 nm [33] | Specialist calibration slides for structured illumination |

| Single-Molecule Localization (SMLM) | ≥ 2× localization precision [33] | Varies with modality | Fluorescent beads for localization precision [32] |

Experimental Protocol: Microscope Calibration Using 3D-Speckler

Regular calibration is essential for maintaining microscope performance and ensuring quantitative accuracy. This protocol utilizes the 3D-Speckler software tool with fluorescent beads to characterize system resolution [32].

Materials and Equipment

- Fluorescent Beads: TetraSpeck Fluorescent Microspheres Size Kit (e.g., 100 nm and 500 nm sizes) [32]

- Immersion Medium: Appropriate for objectives (e.g., Type F oil, water, or silicone oil)

- Microscope System: Any fluorescence microscope with high-NA oil immersion objectives (e.g., 60× or 100×, NA 1.4) [32]

- Software: 3D-Speckler (publicly available) and MATLAB [32]

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation

- Power on the microscope system and select the objective lens for calibration.

- Place a slide with TetraSpeck beads (100 nm) on the microscope stage.

- Locate a field of view (FOV) with evenly distributed beads that are not aggregated.

Image Acquisition

- Finely adjust focus, exposure time, and light source power for optimal imaging.

- For 3D calibration, set the z-range to encompass the entire bead depth with step intervals <200 nm.

- Acquire images at all wavelengths used in your research for chromatic aberration measurement.

- Repeat acquisition at several different slide locations for robust calibration.

- Switch to a slide with larger TetraSpeck beads (500 nm) and repeat the imaging process.

Software Analysis with 3D-Speckler

- Open 3D-Speckler and load acquired bead images.

- Use semi-automated particle detection to identify fluorescent beads.

- Analyze full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) based on 2D/3D Gaussian fits to intensity profiles.

- Determine lateral resolution from 100 nm bead images (should approximate system PSF).

- Validate size measurement accuracy using 500 nm bead data.

- Measure chromatic aberrations by calculating distance between fluorophore centers of different wavelengths within single beads.

Experimental Protocol: Proper Application of Immersion Oil

Correct technique for applying immersion oil is critical for achieving theoretical resolution and preventing objective lens damage.

Materials

- High-quality immersion oil (type matched to application)

- Lens cleaning solution and lint-free lens paper

- Microscope with oil immersion objectives

Step-by-Step Procedure

Preparation

- Verify microscope compatibility with immersion oil.

- Thoroughly clean the objective lens using lens cleaning solution and lens paper [31].

Oil Application

- Place a small drop of immersion oil directly on the cover slip over the specimen, or apply it to the tip of the oil immersion objective [31].

- Use oil sparingly—a single drop is typically sufficient.

Imaging

- Slowly lower the oil immersion objective lens into the drop of oil on the cover slip.

- Ensure the oil forms a continuous connection between the lens and cover slip without air bubbles [31].

- Following image acquisition, carefully raise the objective and clean the lens thoroughly using lens paper.

Objective lenses and immersion oils function as an integrated system that fundamentally determines the resolution capabilities of fluorescence microscopes. The precise matching of refractive indices through proper immersion oil selection directly enables the higher numerical apertures required for advanced imaging techniques, including super-resolution methods. Regular calibration using standardized protocols and materials remains essential for maintaining system performance, validating quantitative measurements, and ensuring the reproducibility of imaging data in cell biology research and drug development. By adhering to these detailed application notes and protocols, researchers can consistently achieve optimal image resolution and reliably interpret subcellular structures and processes.

Practical Protocols: From Sample Preparation to Live-Cell Imaging Applications

Step-by-Step Sample Preparation and Staining for Mammalian Cells

Within the broader framework of establishing robust protocols for fluorescence microscopy in cell imaging research, proper sample preparation is the cornerstone of obtaining reliable and high-quality data. This foundational step determines the success of all subsequent imaging and analysis, especially in critical fields like drug development where quantitative results depend on reproducible staining methods. This application note provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for preparing and staining mammalian cells for fluorescence microscopy, encompassing everything from basic cell culture to advanced labeling techniques, complete with optimized protocols and troubleshooting guidance to ensure research reproducibility.

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues the fundamental materials required for the sample preparation and staining workflows described in this document.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Fluorescence Microscopy

| Item | Function/Application | Example Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Transfection reagent for plasmid DNA delivery into cultured cells. [34] | #11668030 [34] |

| Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium | Diluent for transfection complexes; reduces toxicity during transfection. [34] | #31985070 [34] |

| DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | Blue-fluorescent nuclear and chromosome counterstain that binds to AT regions of DNA. [35] | D1306 [35] |

| Complete DMEM Media | Standard cell culture medium for maintaining mammalian cells. [34] | N/A |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Essential supplement for cell culture media, providing growth factors and nutrients. [34] | #A3840101 [34] |

| Glass Bottom Dishes | Specialized dish for high-resolution microscopy, allowing oil immersion lens access. [34] | P35GC-1.5-14-C [34] |

| Mammalian Expression Plasmids | Genetically encoded tags (e.g., mCherry-TOMM20) for fluorescently labeling cellular structures. [34] | #55146 (Addgene) [34] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Transient Transfection for Live-Cell Imaging

This protocol enables the expression of fluorescently tagged proteins, such as mitochondrial markers, in mammalian cells for live-cell imaging experiments. [34]

Procedure

- Day 0: Seed Cells. Seed U2OS cells (or your chosen mammalian cell line) onto 35-mm glass-bottom dishes at ~20-30% confluency. Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for approximately 24 hours until they reach ~80% confluency. [34]

- Day 1: Prepare Transfection Complexes.

- Thaw plasmid(s) and dilute to the desired concentration in 100 µL of Opti-MEM. For example, use 500 ng for mCherry-TOMM20 and 250 ng for ATP5F1B-tGFP. [34]

- In a separate microfuge tube, add 100 µL of Opti-MEM and 4 µL of Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent per transfection. Mix gently. [34]

- Combine the two mixtures (total volume ~204 µL). Mix gently and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes to allow complex formation. [34]

- Transfect Cells. Take the cells from the incubator and add the transfection mixture dropwise to the culture dish. Gently swirl the dish to distribute evenly. Return to the 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator for 5 hours. [34]

- Change Media. After the 5-hour incubation, replace the transfection media with fresh, pre-warmed Complete DMEM media to reduce toxicity. [34]

- Day 2: Perform Imaging. Conduct live-cell imaging experiments approximately 24 hours post-transfection. [34]

Workflow Visualization

Protocol 2: DAPI Staining for Nuclear Counterstaining

DAPI is a widely used blue-fluorescent dye for labeling cell nuclei in fixed samples. Follow this standardized protocol for consistent results. [35]

Procedure

- Prepare Staining Solution.

- Prepare a 14.3 mM (5 mg/mL) DAPI stock solution by adding 2 mL of deionized water or dimethylformamide to the vial. Sonicate if necessary to dissolve. This stock can be stored at 2–6°C for 6 months or at ≤ –20°C for longer. [35]

- Create a 300 µM intermediate dilution by adding 2.1 µL of stock to 100 µL PBS. [35]

- Dilute the intermediate solution 1:1,000 in PBS to make a working 300 nM DAPI stain solution. [35]

- Label Fixed Cells.

- Culture, fix, and permeabilize cells on coverslips or glass-bottom dishes using a method appropriate for your sample. [35]

- Wash the fixed/permeabilized cells 1-3 times with PBS. [35]

- Add sufficient 300 nM DAPI stain solution to cover the cells. [35]

- Incubate for 1–5 minutes, protected from light. [35]

- Remove the stain solution and wash the cells 2-3 times with PBS. [35]

- Proceed with mounting (if required) and image using a DAPI-compatible filter set. [35]

Spectral Properties

Table 2: DAPI Spectral Information for Microscope Setup

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Excitation/Emission | 358 nm / 461 nm [35] |

| Standard Filter Set | DAPI [35] |

| Recommended Storage | ≤ –20°C [35] |

Safety Note: DAPI is a known mutagen and should be handled with appropriate care, using personal protective equipment. [35]

Advanced Applications

Advanced Technique: Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) Microscopy

TIRF is ideal for imaging events at the plasma membrane with high signal-to-noise. It uses an evanescent field that only excites fluorophores within ~100 nm of the coverslip, effectively excluding signal from the cell interior. [36]

Key Considerations

- Optogenetics Integration: TIRF is perfectly suited for visualizing optogenetically controlled protein translocation to the membrane, such as CRY2-CIBN dimerization systems. [36]

- Equipment: Requires a high numerical aperture (NA) objective lens (e.g., 60×, 1.5 NA) and lasers appropriate for your fluorophores. [36]

Advanced Technique: Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM)

For structures beyond the resolution limit of conventional light microscopy, like extracellular vesicles (EVs), CLEM combines fluorescence localization with ultrastructural detail from TEM. [37]

- Sample Preparation: Isolate structures of interest (e.g., EVs) and stain membranes with a lipophilic dye (e.g., FM1-43). [37]

- Correlative Imaging: First, image the sample using laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) to locate fluorescent signals. Subsequently, image the exact same region using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with negative staining to visualize nanostructure. [37]

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Table 3: Common Issues and Recommended Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Transfection Efficiency | Poor complex formation; cell confluency too high/low. | Ensure accurate DNA:reagent ratios; seed cells for 70-80% confluency at transfection. [34] |

| High Cell Death Post-Transfection | Transfection reagent cytotoxicity. | Reduce complex incubation time (e.g., 5 hours) before replacing with fresh complete media. [34] |

| Weak or No DAPI Signal | Inadequate permeabilization; dye concentration too low. | Verify permeabilization step; ensure DAPI working solution is 300 nM; check microscope lamp and filters. [35] |

| High Background Fluorescence | Incomplete washing; non-specific antibody binding. | Increase number and volume of washes after staining steps; include blocking steps for immunolabeling. |

| Poor TIRF Penetration/Illumination | Incorrect laser alignment; dirty coverslip. | Realign lasers for critical angle; thoroughly clean coverslips before use. [36] |

Mastering the fundamentals of mammalian cell preparation and staining is a prerequisite for generating publication-quality images and reliable quantitative data in fluorescence microscopy. The protocols detailed here—from transient transfection for live-cell analysis to fundamental DAPI staining—provide a robust foundation. Furthermore, the integration of advanced techniques like TIRFM and CLEM enables researchers to push the boundaries of spatial resolution, offering deeper insights into cellular structures and functions critical for modern cell biology and drug development research.

Protocol for Cell Viability Assessment Using FDA/PI Live-Dead Staining

The assessment of cell viability is a cornerstone of biological research, playing a critical role in fields ranging from basic cell biology to preclinical drug development and biomaterial testing. Among the various methods available, fluorescence-based viability assays that simultaneously evaluate plasma membrane integrity and enzymatic activity provide superior accuracy and specificity. The Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) and Propidium Iodide (PI) live-dead staining protocol represents a robust, dual-parameter approach for distinguishing between viable, compromised, and dead cell populations. This application note details a standardized FDA/PI staining protocol optimized for fluorescence microscopy, framed within the broader context of advancing reproducible fluorescence imaging methodologies in cell research.

This method leverages two distinct mechanistic principles: FDA, a non-fluorescent, cell-permeant compound, is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases in viable cells to produce fluorescent fluorescein, generating a green fluorescent signal. In contrast, PI is a membrane-impermeant dye that only enters cells with compromised plasma membranes, binding to nucleic acids and producing a red fluorescence. This differential staining allows for clear discrimination between live (green), dead (red), and injured or metabolically inactive cells (unstained or dual-stained) [38]. The protocol described herein has been validated against other established methods like flow cytometry, demonstrating a strong correlation (r = 0.94), while offering the added benefit of direct morphological assessment [39].

Principle and Mechanism of FDA/PI Staining

The FDA/PI assay provides a reliable assessment of cell status based on two key cellular characteristics: enzymatic activity and plasma membrane integrity. The workflow and underlying biochemical mechanisms are illustrated in the following diagram.

Diagram 1: Mechanism of FDA/PI live-dead staining. The process involves adding dyes, incubation, and analysis. In live cells, FDA is converted to green fluorescein, while PI is excluded. In dead cells, PI enters through damaged membranes and emits red fluorescence.

This staining mechanism allows researchers to quantitatively assess cell viability and monitor changes in real-time. The distinct spectral separation of green (fluorescein, ~520 nm) and red (PI, ~620 nm) fluorescence enables clear differentiation of cell populations when imaged with standard FITC and TRITC/Rhodamine filter sets, respectively [40] [38]. Unlike single-dye methods, this dual-staining approach helps identify an intermediate population of cells that may have reduced metabolic activity but still maintain membrane integrity, providing a more nuanced view of cell health.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential reagents and equipment required for performing the FDA/PI live-dead staining protocol.

Table 1: Essential reagents and equipment for FDA/PI live-dead staining

| Item Name | Function/Description | Storage Conditions | Handling Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | Non-fluorescent substrate converted to green fluorescent fluorescein by intracellular esterases in live cells [38]. | -20°C in airtight container, protected from light [41]. | Prepare fresh stock solutions for each experiment; avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Membrane-impermeant nucleic acid stain that labels dead cells with compromised membranes with red fluorescence [42]. | 2-8°C in airtight container, protected from light [41]. | Handle with care; mutagen. Use appropriate personal protective equipment. |

| Staining Buffer | Isotonic solution (e.g., 0.85% saline, PBS) for dye dilution and cell resuspension; minimizes staining artifacts [42]. | Room temperature or refrigerated. | Ensure protein-free or low-protein (<1%) for optimal dye function [43]. |

| Fluorescence Microscope | Imaging system with appropriate filters for fluorescein (Ex/Em ~495/520 nm) and PI (Ex/Em ~535/615 nm) [39]. | N/A | Adjust exposure to avoid saturation and ensure clear signal separation. |

| Cell Counting Chamber | Automated cell counter or hemocytometer for quantitative analysis. | N/A | Ensure surfaces are clean before loading sample [41]. |

Reagent Preparation

- FDA Stock Solution: Prepare a concentrated stock solution (e.g., 1-5 mM) in high-quality dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Aliquot and store at -20°C. Avoid repeated freezing and thawing.

- PI Stock Solution: Commercially available solutions are typically provided at concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 1.0 mM. Store at 2-8°C protected from light [42] [41].

- Working Stain Solution: Prepare the working mixture immediately before use by diluting the stock solutions in an appropriate protein-free buffer. A common ratio is 1 µL of each dye stock per 18-20 µL of cell suspension, though optimal concentrations should be determined empirically for each cell type [41].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Staining and Imaging Workflow

The entire procedure, from cell preparation to image acquisition, can be completed in less than 30 minutes. The following diagram outlines the key steps.

Diagram 2: FDA/PI staining and imaging workflow. Key experimental steps with critical technical notes for optimal results.

Detailed Procedural Steps

Cell Preparation: Harvest cells from culture or post-treatment. Pellet cells by gentle centrifugation (e.g., 300 × g for 5 minutes) and wash once with a protein-free buffer such as 0.85% saline or PBS to remove residual culture medium that can interfere with staining [42]. Resuspend the cell pellet to an appropriate density (e.g., OD600 of ~1.0 for yeast, or 1×10⁴–1×10⁶ cells/mL for mammalian cells) in the same buffer [43] [42].

Staining:

- Combine 18 µL of the well-mixed cell suspension with 1 µL of FDA stock solution and 1 µL of PI stock solution directly on a slide or in a microcentrifuge tube [41]. The final working concentrations are typically around 5 µM for both FDA and PI [44].

- Mix the solution gently but thoroughly by pipetting. Avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Incubate the staining mixture for 5 to 15 minutes at room temperature, protected from light [44] [41]. The optimal incubation time should be determined for each specific cell type.

Image Acquisition:

- After incubation, pipette an appropriate volume of the stained cell suspension onto a clean microscope slide. For some automated counters, a specific chamber height (e.g., 50 µm) is used [41].

- Allow the cells to settle for a brief period to minimize movement during imaging.

- Using a fluorescence microscope equipped with standard FITC (for FDA/green) and TRITC (for PI/red) filter sets, acquire images. Adjust the exposure time for each channel to ensure the cells are neither under- nor over-exposed [41].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Comparison with Other Viability Assays

The performance of the FDA/PI staining method has been systematically compared to other common viability assessment techniques. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from comparative studies.

Table 2: Comparison of cell viability assessment methods

| Method | Principle | Time Required | Key Advantages | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA/PI Staining + Fluorescence Microscopy | Membrane integrity (PI) & enzymatic activity (FDA) [38]. | ~20-30 min [44] [41]. | Preserves cell morphology; low cytotoxicity; enzyme-specific live cell signal [38]. | Manual analysis can be time-consuming; potential for user bias [39]. |

| SYTO 9/PI Staining + Flow Cytometry | Membrane integrity & nucleic acid binding with FRET [42]. | ~15-30 min staining + flow cytometry time [42]. | High-throughput; objective; distinguishes live, dead, and damaged cells quantitatively [42]. | Requires suspended cells; expensive instrumentation; no morphological context [39]. |

| Trypan Blue (TB) Exclusion | Membrane integrity; dead cells stain blue [38]. | ~5-10 min. | Inexpensive; widely available; no special equipment needed. | Cytotoxic; short counting window; can underestimate viability, especially in sensitive cells [38]. |

| Colony Forming Unit (CFU) Assay | Clonogenicity (ability to proliferate) [42]. | 24-48 hours incubation [42]. | Gold standard for proliferative capacity. | Very slow; only detects culturable cells; does not report on initial membrane damage [42]. |

A 2025 comparative study on biomaterial cytotoxicity reported a strong correlation (r = 0.94, R² = 0.8879, p < 0.0001) between viability measurements obtained via FDA/PI fluorescence microscopy and multi-parameter flow cytometry, validating the reliability of the FDA/PI method [39].

Image Analysis and Viability Calculation

- Cell Counting: Analyze the acquired fluorescence images to count the cells in each category.

- Viable Cells: Exhibit only green fluorescence (from FDA hydrolysis).

- Non-Viable Cells: Exhibit red fluorescence (from PI) with little to no green fluorescence.

- Note: Cells showing both green and red fluorescence may represent injured or late apoptotic cells and are typically classified as non-viable.