Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors for Physiological Monitoring: A 2025 Review of Principles, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive review of Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensor technology for physiological monitoring, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors for Physiological Monitoring: A 2025 Review of Principles, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensor technology for physiological monitoring, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of FBGs, including their inherent immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI) and high sensitivity, which make them ideal for clinical settings like MRI suites. The manuscript details methodological advances in wearable FBG design for vital sign and body motion tracking, examines critical challenges such as cross-sensitivity and integration into textiles, and presents a comparative analysis with conventional electronic sensors. By synthesizing recent research and future directions, this review serves as a strategic resource for innovating next-generation biomedical monitoring systems.

The Foundation of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing: Core Principles and Advantages for Biomedical Applications

Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGs) have emerged as a transformative technology in the field of optical sensing, particularly for physiological monitoring research where precision, miniaturization, and electromagnetic immunity are critical. An FBG is an optical sensor characterized by a periodic modulation of the refractive index along the core of an optical fiber [1]. This modulation forms a grating that acts as a wavelength-specific reflector. The fundamental principle underlying FBG sensing is that the central reflected wavelength, known as the Bragg wavelength (λB), shifts in response to external physical parameters such as temperature change and mechanical strain [1]. This direct relationship between the wavelength shift and environmental perturbations forms the basis for their extensive use in high-precision sensing applications, from structural health monitoring to biomedical device integration [2] [3].

The attractiveness of FBG sensors for physiological monitoring stems from their inherent advantages. These include their small size and lightweight nature, which allow for minimal invasiveness; their complete immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI), enabling operation in MRI environments and alongside other electronic medical equipment; their corrosion resistance; and their capacity for multiplexing several sensors on a single optical fiber [2] [3]. This last feature is particularly valuable for distributed sensing of physiological parameters, such as mapping pressure points across a wheelchair cushion or measuring strain at multiple points along a tendon [3].

The Bragg Grating Theory of Fiber

The theoretical foundation of FBG operation is rooted in the principles of light diffraction and interference in periodic structures. The grating within the optical fiber core consists of alternating regions with different refractive indices. When broadband light is launched through the fiber, each grating plane reflects a small portion of the incident light. For most wavelengths, these reflected light waves become phase-mismatched and destructively interfere. However, at one specific wavelength, the Bragg wavelength, the reflected waves from each grating plane undergo constructive interference [1]. This results in a strong reflected signal at this wavelength, while all other wavelengths are transmitted through the grating.

The condition for this constructive interference is defined by the Bragg equation:

λB = 2neffΛ

In this equation [1]:

- λB is the Bragg wavelength (the peak reflection wavelength).

- neff is the effective refractive index of the fiber core.

- Λ is the period of the grating (the spatial distance between two successive refractive index modulations).

When the FBG is subjected to external perturbations like strain or temperature changes, both the grating period (Λ) and the effective refractive index (neff) are altered. This causes a shift in the Bragg wavelength (ΔλB), which can be measured with high precision. Monitoring this wavelength shift allows for the quantitative determination of the applied stimulus, making the FBG a highly sensitive transducer for physical parameters [1].

Quantitative Response to Strain and Temperature

The sensitivity of the FBG sensor to strain and temperature is derived by differentiating the Bragg wavelength equation, resulting in a relationship that expresses the relative wavelength shift (ΔλB/λB) [4].

Response to Strain

When an FBG is subjected to mechanical strain, two effects occur: the physical elongation or compression of the fiber changes the grating period (Λ), and the stress-optic effect alters the effective refractive index (neff). The combined effect leads to a wavelength shift described by:

ΔλB / λB = (1 - pe) * Δε

Where [4]:

- Δε is the applied strain variation.

- pe is the photo-elastic constant of the optical fiber material, which accounts for the stress-induced change in the refractive index.

The strain sensitivity is typically condensed into a strain sensitivity coefficient, Kε. For standard silica fibers, the strain sensitivity is approximately ~1.2 pm/µε (picometers per microstrain) [5].

Response to Temperature

A change in temperature affects the FBG through two primary mechanisms: the thermal expansion (or contraction) of the fiber material, which changes the grating period (Λ), and the thermo-optic effect, which alters the effective refractive index (neff). The temperature-induced wavelength shift is given by:

ΔλB / λB = (αf + ξ) * ΔT

Where [4]:

- ΔT is the temperature change.

- αf is the thermal expansion coefficient of the fiber material.

- ξ is the thermo-optic constant.

This sensitivity is typically condensed into a temperature sensitivity coefficient, KT. For standard silica fibers, the temperature sensitivity is typically about ~10 pm/°C [5].

Table 1: Standard Sensitivity Coefficients for Silica FBG Sensors

| Parameter | Sensitivity Coefficient | Typical Value |

|---|---|---|

| Axial Strain | Kε | ~1.2 pm/µε [5] |

| Temperature | KT | ~10 pm/°C [5] |

The Cross-Sensitivity Challenge

A fundamental challenge in FBG sensing is the dual sensitivity of the Bragg wavelength [4]. Since both strain and temperature produce a wavelength shift, it is impossible to distinguish between the two effects using a single standard FBG. This cross-sensitivity can lead to significant measurement errors in physiological monitoring, where temperature fluctuations and mechanical strain often occur simultaneously (e.g., in wearable sensors for joint movement monitoring) [5].

Advanced FBG Designs for Enhanced Sensitivity and Discrimination

Research has led to advanced FBG designs and interrogation schemes to overcome the limitations of standard FBGs, particularly for high-precision applications like physiological monitoring.

Sensitivity Enhancement via Exceptional Points

Recent investigations have integrated concepts from non-Hermitian photonics, specifically Exceptional Points (EPs), to dramatically enhance FBG sensitivity. EPs are spectral singularities where eigenvalues and eigenvectors coalesce, resulting in an extreme sensitivity to external perturbations. By engineering the FBG's grating profile to operate near an EP, significant sensitivity enhancement has been achieved under a power interrogation scheme [5].

Table 2: Enhanced Sensitivity of EP-Engineered FBGs

| Parameter | Standard FBG Sensitivity | EP-Engineered FBG Sensitivity | Enhancement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | ~10 pm/°C [5] | ~9.3 dBm/°C [5] | Nearly an order-of-magnitude |

| Axial Strain | ~1.2 pm/µε [5] | ~0.5 dBm/µε [5] | Nearly an order-of-magnitude |

These EP-engineered FBGs demonstrate nearly an order-of-magnitude improvement in sensitivity. To manage cross-sensitivity, a sensitivity matrix-based approach can be implemented, enabling accurate simultaneous detection of multiple parameters [5].

Simultaneous Strain and Temperature Measurement

Another approach to resolving the cross-sensitivity issue is the use of Polarization-Maintaining FBGs (PM-FBGs). These sensors possess a built-in birefringence, which results in two distinct Bragg peaks (λ1, λ2) in the reflection spectrum, corresponding to two orthogonal polarization axes [6].

The response of these two peaks to strain (ε) and temperature (T) is given by [6]: Δλ1 = a * ΔT + b * Δε Δλ2 = c * ΔT + d * Δε

Here, the sensitivity coefficients (a, b, c, d) for the two peaks are slightly different. By measuring the shifts of both peaks (Δλ1 and Δλ2), the system of two equations can be solved to simultaneously and independently determine the applied temperature change (ΔT) and strain (Δε) [6]. This eliminates the need for complex transducer packaging designed solely to isolate strain.

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols outline standard procedures for characterizing FBG sensors and for implementing a simultaneous strain and temperature measurement system.

Protocol 1: Fundamental Characterization of FBG Strain and Temperature Sensitivity

This protocol describes the process for calibrating a standard FBG sensor to determine its individual strain and temperature sensitivity coefficients [6].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Key Materials for FBG Characterization

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| FBG Sensor | The optical sensor under test, with known initial Bragg wavelength. |

| Optical Interrogator | A high-precision device (e.g., tunable laser interrogator) to measure Bragg wavelength shifts in the picometer (pm) range [6]. |

| Temperature Chamber | A controlled environment (e.g., Votsch VT 7021) for cycling temperature over a defined range (e.g., -20°C to +80°C) [6]. |

| Strain Calibration Bench | A setup capable of applying precise, calibrated strain to the FBG (e.g., from 0 µε to +2145 µε) [6]. |

| Reference Sensors | High-precision electrical temperature probes (e.g., ISOTECH 935-14-61) or PT100 sensors, and reference strain gauges [6]. |

Methodology

- Temperature Sensitivity Calibration:

- Place the FBG sensor inside the temperature chamber alongside a high-precision reference temperature probe.

- Cycle the chamber temperature over the desired range (e.g., -20°C to +80°C) while recording the FBG's Bragg wavelength (λB) and the reference temperature (T) at each stable point.

- Plot the wavelength shift (ΔλB) against the temperature change (ΔT). The slope of the linear fit to this data is the temperature sensitivity coefficient, KT (pm/°C).

- Strain Sensitivity Calibration:

- Mount the FBG sensor on the strain calibration bench, ensuring it is coupled to apply axial strain.

- Apply a sequence of known strain values (e.g., in 10 steps from 0 µε to 2145 µε and back to 0 µε) while recording the Bragg wavelength shift.

- Plot the wavelength shift (ΔλB) against the applied strain (Δε). The slope of the linear fit to this data is the strain sensitivity coefficient, Kε (pm/µε).

Protocol 2: Simultaneous Measurement of Strain and Temperature using PM-FBGs

This protocol details the setup and data processing required to decouple strain and temperature using a single Polarization-Maintaining FBG (PM-FBG) sensor, which is ideal for applications where the two parameters cannot be physically isolated [6].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 4: Key Materials for Simultaneous Measurement

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| PM-FBG Array | A sensor array with multiple PM-FBGs on a single fiber, such as PM-Draw Tower Gratings (PM-DTGs) with an Ormocer coating [6]. |

| Specialized Interrogator | An interrogator capable of detecting both orthogonal polarization responses of the PM-FBGs (e.g., FAZT I4_Bi) [6]. |

| Calibration Setup | Integrated system for applying combined strain and temperature cycles to determine the sensor's specific sensitivity coefficients [6]. |

Methodology

- Sensor Calibration:

- Subject the PM-FBG to a combined calibration cycle of strain (e.g., 0 µε → +2145 µε → 0 µε) and temperature (e.g., -20°C → +120°C → -20°C).

- Use the interrogator to record the wavelength shifts of both Bragg peaks (Δλ1, Δλ2) at each step.

- Perform a multivariate linear regression to determine the four sensitivity coefficients (a, b, c, d) for the equations:

- Δλ1 = a * ΔT + b * Δε

- Δλ2 = c * ΔT + d * Δε

- Operational Measurement:

- Install the calibrated PM-FBG sensor in the test environment.

- Continuously monitor the two Bragg peaks (λ1, λ2) using the specialized interrogator.

- For each measurement instance, calculate the decoupled temperature (ΔT) and strain (Δε) using the inverse of the sensitivity matrix [6]:

- ΔT = ( d * Δλ1 - b * Δλ2 ) / ( a * d - b * c )

- Δε = ( -c * Δλ1 + a * Δλ2 ) / ( a * d - b * c )

- Where the denominator (ad - bc) is the determinant of the matrix.

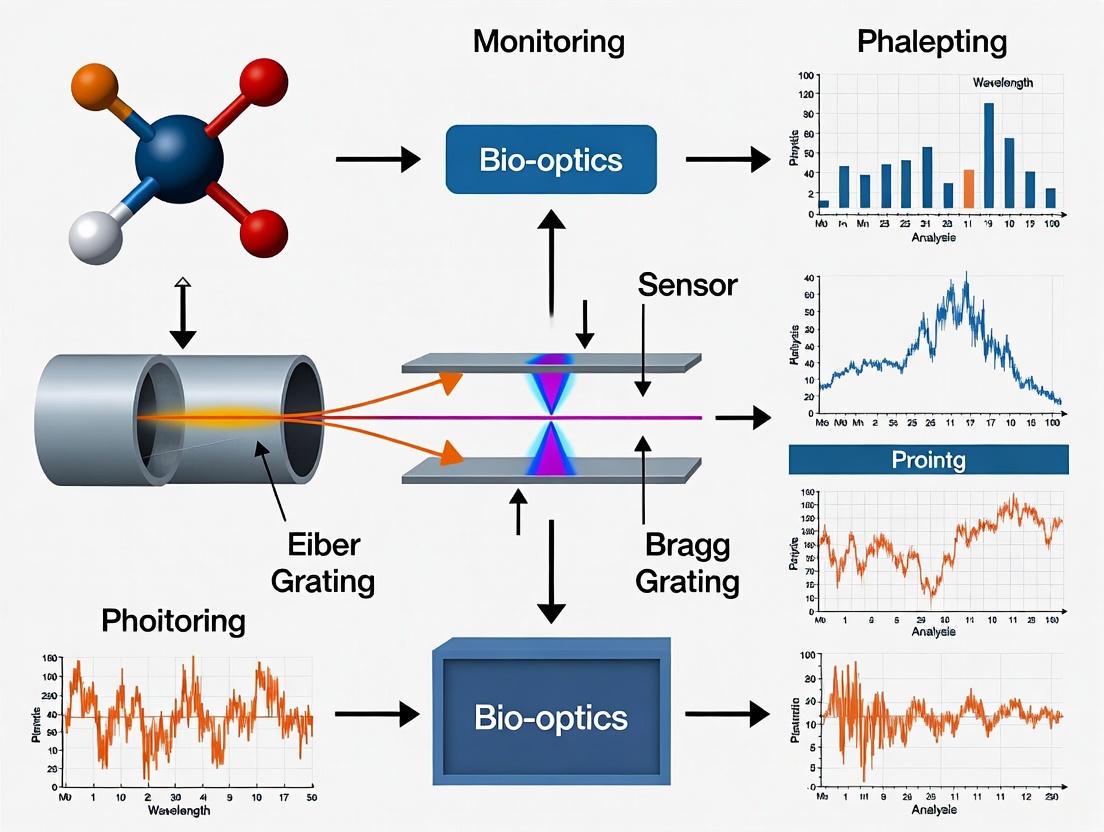

Schematic Diagrams of FBG Operating Principle and Measurement

FBG Operating Principle and Wavelength Shift

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working principle of a Fiber Bragg Grating and how the Bragg wavelength shifts in response to applied strain or temperature changes.

Diagram 1: FBG operating principle and wavelength shift.

Simultaneous Strain and Temperature Measurement Workflow

This flowchart outlines the experimental workflow for achieving simultaneous, decoupled measurements of strain and temperature using a Polarization-Maintaining FBG (PM-FBG).

Diagram 2: Workflow for simultaneous strain and temperature measurement.

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors have emerged as a transformative technology for physiological monitoring in clinical and research settings. Their operation is based on the principle of light reflection from a periodic grating structure inscribed in the optical fiber core, which shifts in response to external physical parameters such as strain, temperature, and pressure [7] [8]. This technical foundation provides a unique combination of advantages that directly address the stringent requirements of clinical environments, where electromagnetic interference (EMI) immunity, miniaturization, and biocompatibility are paramount for patient safety and data integrity [9]. This application note details these core advantages, supported by quantitative data and experimental methodologies, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in the effective deployment of FBG-based sensing systems.

Key Advantages and Quantitative Data

The following sections elaborate on the three key advantages of FBG sensors, with summarized data presented in subsequent tables for clear comparison.

Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) Immunity

A paramount advantage of FBG sensors in clinical settings is their inherent immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI). Since FBGs use light as the information carrier rather than electrical currents, they remain unaffected by strong electromagnetic fields generated by equipment such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanners, electrosurgical units, and other hospital instrumentation [9] [10] [8]. This property ensures reliable and artifact-free signal acquisition, which is critical for patient monitoring during simultaneous diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. This immunity also enhances safety by eliminating the risk of electrical sparks in sensitive environments [9].

Miniaturization and Multiplexing Capability

FBG sensors are inherently small and lightweight, with a standard diameter similar to a human hair (125-250 µm), allowing for integration into minimally invasive surgical tools, catheters, and wearable devices [9] [8]. A single optical fiber can host multiple FBG sensors, a feature known as multiplexing. This enables the simultaneous monitoring of several physiological parameters (e.g., pressure, temperature, and force) from different locations using a single fiber connection, simplifying system design and reducing patient discomfort [10] [8]. Their compact size facilitates embedding into smart textiles for respiratory monitoring and instrumented prosthetics for biomechanical feedback [11] [9].

Biocompatibility and Safety

FBGs offer excellent biocompatibility, particularly polymer optical fibers (POFs), which are more flexible and safer than silica fibers for in-body applications as they are less prone to breaking and causing injury [9]. Silica glass, the primary material for many optical fibers, is chemically passive and biocompatible, making it suitable for intrinsic use in human systems [9]. This, combined with the fact that the sensing mechanism uses light instead of electricity, minimizes risks such as electric shock or thermal heating, making FBGs exceptionally safe for prolonged patient contact and implantable sensing applications [9].

Table 1: Key Advantages of FBG Sensors in Clinical Environments

| Advantage | Technical Basis | Clinical Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| EMI Immunity | Light-based signal transmission; no electrical conductors [10] [8]. | Reliable operation inside MRI suites and alongside other medical electronics; eliminates measurement artifacts. |

| Miniaturization | Small form factor (diameters from 125 µm); flexible [9]. | Enables development of minimally invasive catheters, needles, and wearable sensors. |

| Multiplexing | Multiple FBGs with distinct Bragg wavelengths on a single fiber [10]. | Multi-parameter and multi-point sensing with a single percutaneous entry; reduces system complexity. |

| Biocompatibility | Use of silica glass or biocompatible polymers (POFs) [9]. | Safe for extended contact with tissues and bodily fluids; reduces risk of adverse reaction. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of FBG Sensors in Biomedical Applications

| Measurand | Application Example | Reported Performance | Source Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure | Intravascular blood pressure monitoring [12]. | High sensitivity required for accurate clinical data. | Academic Review [12] |

| Mitral valve apparatus tension measurement [11]. | Ex vivo validation of force-sensing neochordae. | Research Article [11] | |

| Strain | Tendon and ligament force measurement [11]. | Accurate detection of dynamic movements. | Research Article [11] |

| Bone stress analysis during mastication [11]. | Monitoring of biomechanical forces. | Research Article [11] | |

| Temperature | Body temperature monitoring [10]. | Precise measurement for patient vital signs. | Industry Overview [10] |

| Kinematics | Knee joint posture sensing [11]. | Integration into a smart wearable belt. | Research Article [11] |

| Hand movement tracking [11]. | Sensing glove for dynamic finger flexure. | Research Article [11] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a generalized workflow and a specific detailed protocol for implementing FBG sensors in physiological monitoring.

Generalized Workflow for FBG-Based Physiological Sensing

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for developing and deploying an FBG sensing system for clinical research.

Detailed Protocol: FBG-Based Pressure Sensing for Intravascular Applications

Objective: To measure intravascular blood pressure in real-time using a fiber-optic pressure sensor based on an FBG integrated with a diaphragm mechanism [12].

Materials:

- Single-mode optical fiber with an inscribed FBG.

- Interrogator unit with specified wavelength resolution (e.g., ±1 pm).

- Pressure chamber for calibration.

- Diaphragm housing fixture.

- Data acquisition software.

- Physiological saline solution.

Methodology:

- Sensor Fabrication: Encapsulate the FBG within a custom-designed diaphragm structure. The external pressure deflects the diaphragm, transferring strain to the FBG [12].

- Calibration:

- Connect the sensor to the interrogator.

- Place the sensor assembly inside the pressure chamber.

- Expose the sensor to known pressure levels (e.g., 0 to 300 mmHg) in increments.

- Record the corresponding Bragg wavelength shift (ΔλB) at each pressure point at a constant temperature.

- Generate a calibration curve (Pressure vs. ΔλB) and calculate the pressure sensitivity in pm/mmHg.

- In-Vitro Validation: Submerge the sensor in a bath of physiological saline at 37°C to simulate the vascular environment and validate performance.

- Data Acquisition: During measurement, the interrogator continuously monitors the FBG's Bragg wavelength. The recorded wavelength data is converted to pressure values in real-time using the established calibration curve.

Diagram: Core Operating Principle of an FBG Sensor

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operating principle of an FBG sensor, where changes in the physical environment cause a measurable shift in the reflected wavelength.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for FBG Sensor Development in Biomedical Research

| Item | Function / Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Photosensitive Optical Fiber | The substrate for FBG inscription; typically germanosilicate glass for UV writing [7] [9]. | Photosensitivity determines the efficiency of the grating inscription process. |

| Ultraviolet (UV) Laser System | Used with a phase mask to create the periodic refractive index modulation in the fiber core [7] [8]. | Wavelength and coherence length are critical for creating high-quality gratings. |

| Femtosecond (fs) Laser | An alternative for fabricating gratings in non-photosensitive fibers and creating complex structures [7]. | Enables direct inscription in standard fibers without hydrogen loading. |

| Optical Interrogator | The instrument that emits light into the fiber and detects the wavelength shifts from the FBGs [7]. | Wavelength resolution, scan rate, and channel count define system performance. |

| Biocompatible Polymer Coating | A protective layer (e.g., acrylate, polyimide) applied to the fiber post-inscription for mechanical and biological protection [7] [9]. | Must ensure biocompatibility and enhance durability without compromising sensitivity. |

| Polymer Optical Fiber (POF) | A flexible and fracture-tolerant alternative to silica fiber, ideal for wearable sensors [9]. | Higher elastic strain limits and better compatibility with organic materials. |

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors have emerged as a transformative technology in physiological monitoring research, offering distinct advantages for measuring biomechanical forces, body temperature, and biochemical analytes. Their inherent immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI), small size, and passive operation make them exceptionally suitable for use in MRI environments, implantable devices, and long-term patient monitoring [7]. An FBG sensing system operates on the principle of wavelength-based optical transduction, where physiological changes induce a measurable shift in the Bragg wavelength of light reflected by the grating [7]. This application note details the fundamental components of an FBG system and provides a standardized protocol for researchers in biomedical and pharmaceutical development to implement this technology for accurate and reliable physiological sensing.

Core Components of an FBG Sensing System

A functional FBG sensing system comprises four essential components: the optical fiber with the inscribed FBG sensor, the interrogator (or demodulator), the light source (often integrated within the interrogator), and the data acquisition and processing unit.

Optical Fiber and FBG Sensor

An optical fiber consists of a core, cladding, and a protective jacket. The FBG is a periodic modulation of the refractive index within the core of a single-mode optical fiber, typically inscribed using ultraviolet laser light via phase mask, point-by-point, or interferometric techniques [7]. More recently, femtosecond laser inscription has enabled the fabrication of gratings in a wider variety of fiber types without the need for hydrogen loading, providing greater flexibility for specialized sensor designs [7].

The fundamental principle of operation is governed by the Bragg condition, where the central wavelength of the reflected light, known as the Bragg wavelength (( \lambdaB )), is defined as: [ \lambdaB = 2 \cdot n{eff} \cdot \Lambda ] where ( n{eff} ) is the effective refractive index of the fiber core and ( \Lambda ) is the grating period [7]. Changes in strain and temperature directly alter ( n{eff} ) and/or ( \Lambda ), resulting in a shift of the Bragg wavelength (( \Delta \lambdaB )) [7]. For physiological monitoring, the FBG is often packaged or functionalized to respond to a specific biological stimulus, such as pressure, temperature, or a particular biochemical.

Interrogator (Demodulator)

The interrogator is the core electronic unit that detects and processes the optical signal from the FBG sensor. Its primary function is to illuminate the FBG and precisely measure the wavelength shift of the reflected light, converting it into a digital, engineering-relevant value [13]. Interrogators employ various demodulation techniques, including tunable filtering, interferometry, and spectroscopy. Recent research focuses on overcoming the cost-size-accuracy trade-offs, with novel systems using tunable lasers and advanced peak-finding algorithms deployed on microcontrollers achieving compact sizes (100 mm × 100 mm × 10 mm) and demodulation accuracies with a mean absolute error of 9.6 pm [14]. Key specifications for selecting an interrogator include wavelength range, number of channels, sampling rate, and wavelength accuracy.

Light Source

A broadband light source, such as an amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) source, is typically integrated into the interrogator. This source emits light over a wide spectrum that encompasses the Bragg wavelengths of all FBG sensors in the system. For the FBGs described in these results, the operational wavelength range is generally in the C-band, around 1510 to 1590 nm [15] [16] [17]. In alternative systems, a tunable laser source may be used, which scans across a range of wavelengths to identify the peak reflection from the FBG [14].

Data Acquisition and Processing Unit

This unit comprises the software and hardware interfaces that collect the wavelength data from the interrogator, perform necessary calculations and calibrations, and present it to the researcher. Communication is typically handled via protocols like USB, Ethernet, or TCP/IP [15] [16] [17]. The software allows for real-time data visualization, logging, and setting of alarm thresholds based on the measured physiological parameters.

Performance Comparison of Commercial and Research Interrogators

The following table summarizes the key specifications of several commercial and research-grade FBG interrogators, aiding in the selection of an appropriate system for physiological monitoring studies.

Table 1: Performance Specifications of Selected FBG Interrogators

| Product / System | Wavelength Range (nm) | Channels / Sensors per Channel | Max. Sampling Rate | Wavelength Accuracy | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WaveCapture FBG System [15] | 1510 - 1590 | 1, 4, 8, or 16 channels | 5 kHz | ±5 pm | High EOL accuracy, USB 2.0, for harsh environments and various sensing applications. |

| GTR FBG Interrogator [16] | 1515 - 1585 | 1 channel / Up to 8 sensors | 19.23 kHz | < 5 pm repeatability | Miniature size (100x114x35 mm), low weight (310 g), ideal for portable and OEM integrations. |

| FBGuard 1550 [17] | 1505 - 1590 | Up to 16 channels / 40 sensors per channel | 11 kHz (Fast option) | ±5 pm (EOL) | Industrial-grade, static & dynamic measurement, up to 640 sensors total. |

| SOFO VII/MuST [18] | N/A | 4 channels / 7-25 FBGs per channel | N/A | N/A (NIST traceable) | Portable, battery-operated, integrated PC & touch screen for field use. |

| Novel Demodulation System [14] | 1525 - 1565 (C-band) | N/A | 100 Hz | 9.6 pm MAE | Research prototype; compact (100x100x10 mm), cost-effective, uses GRU peak-finding algorithm. |

Experimental Protocol: FBG-Based Temperature Sensing for Physiological Applications

This protocol outlines a methodology for utilizing an FBG sensor to measure temperature, which can be adapted for monitoring core body temperature or skin temperature in clinical research settings.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for FBG Temperature Sensing Experiments

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| FBG Interrogator | e.g., GTR or WaveCapture system, to illuminate the FBG and measure wavelength shifts. |

| Single-Mode Optical Fiber | The medium containing the inscribed FBG sensor. |

| FC/APC Connectorized Patch Cable | Connects the FBG sensor to the interrogator with minimal back-reflection. |

| Temperature Calibration Chamber | A controlled environment (e.g., oven or water bath) for calibrating the FBG's temperature response. |

| NIST-Traceable Reference Thermometer | Provides ground truth temperature readings for calibration. |

| Data Acquisition Software | Provided with the interrogator or custom-built (e.g., in LabVIEW or Python) for logging data. |

| Medical-Grade Biocompatible Coating | (For implantable/ex vivo use) Encapsulates the FBG for biocompatibility and mechanical protection. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sensor Preparation: Inscribe or procure an FBG sensor with a known central wavelength within the interrogator's operating range (e.g., ~1550 nm). If intended for contact with biological tissues, the sensor must be coated with a suitable, medically approved biocompatible polymer (e.g., silicone) to ensure safety and stability.

- Optical Connection: Connect the FC/APC patch cable from the interrogator's optical output to the FBG sensor. Ensure all connections are secure to prevent signal loss.

- System Power-Up: Power on the interrogator and start the data acquisition software. Verify that the software detects the interrogator and can display the reflected spectrum from the FBG.

- Temperature Calibration: a. Place the FBG sensor and the NIST-traceable reference thermometer in the temperature calibration chamber, ensuring good thermal contact. b. Ramp the chamber temperature through a series of stable points across the expected physiological range (e.g., 30°C to 45°C). c. At each stable temperature point, record the Bragg wavelength (( \lambdaB )) from the interrogator and the corresponding temperature (T) from the reference thermometer. d. Perform a linear regression analysis on the collected data to determine the temperature sensitivity coefficient, ( KT ) (typically in pm/°C), from the equation: [ \Delta \lambdaB = KT \cdot \Delta T ] where ( \Delta \lambda_B ) is the measured wavelength shift and ( \Delta T ) is the temperature change.

- Experimental Measurement: a. Deploy the calibrated FBG sensor in the physiological environment (e.g., fixed on the skin or immersed in a cell culture). b. Initiate continuous data acquisition from the interrogator. c. The data acquisition software should now convert the real-time wavelength shifts into temperature values using the established calibration coefficient ( K_T ).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the collected temperature data, noting rates of change, stability, and any correlations with other experimental variables or stimuli.

System Workflow and Signal Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of information and the relationship between the core components in a typical FBG sensing system.

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors have emerged as advanced tools for monitoring a wide range of physical parameters in various fields, including structural health, aerospace, and biomedical applications [19]. An FBG is an optical sensor that relies on a periodic modulation of the refractive index along the core of an optical fiber, forming a grating that selectively reflects light at a specific wavelength known as the Bragg wavelength [1]. The fundamental principle behind FBG sensing is based on the fact that the Bragg wavelength shifts in response to external factors such as temperature, strain, pressure, and chemical interactions [19] [1]. This ability to capture changes in real-time makes FBG sensing a powerful tool for precision sensing in physiological monitoring [1].

The theory behind Fiber Bragg Gratings is based on the principle of light diffraction. A Bragg grating is a periodic structure with alternating regions of different refractive indices. When light passes through the fiber, the periodic changes in the refractive index cause constructive interference, resulting in the reflection of light at a specific wavelength [1]. This Bragg wavelength (λ~B~) is determined by the equation:

λ~B~ = 2n~eff~Λ

Where:

- λ~B~ is the Bragg wavelength (the wavelength of the reflected light)

- n~eff~ is the effective refractive index of the fiber core

- Λ is the period of the grating (the distance between two successive refractive index changes) [19] [1]

When an external force (like temperature or strain) is applied to the fiber, the grating period (Λ) and/or the refractive index (n~eff~) changes, causing a shift in the Bragg wavelength (Δλ~B~). This shift is directly proportional to the magnitude of the external perturbation, making FBG sensors valuable for real-time monitoring of physiological signals [19] [1].

The Bragg Wavelength Shift Mechanism

Fundamental Principles

The Bragg wavelength shift mechanism forms the cornerstone of FBG sensing technology for physiological monitoring. When an FBG sensor is subjected to external stimuli, such as mechanical strain or temperature variations, both the effective refractive index (n~eff~) and the grating period (Λ) undergo modification, resulting in a measurable shift in the reflected Bragg wavelength [19]. This relationship is quantitatively described by the following equation:

Δλ~B~ = 2 • [(∂n~eff~/∂T)ΔT + n~eff~(∂Λ/∂ε)Δε]

Where:

- Δλ~B~ is the shift in the Bragg wavelength

- ΔT is the temperature change

- Δε is the strain change [19]

For physiological sensing, this fundamental principle can be adapted to measure specific biological parameters. For instance, when employing a specialized coating sensitive to a particular biological compound, the stress induced in this coating layer causes a shift in the Bragg wavelength. When the sensor's temperature remains constant, the Bragg wavelength shift may be expressed as:

Δλ~B~/λ~B~ = K~ε~ × ε

Where ε is the axial stress of the FBG caused by the expansion or contraction of the specialized coating layer, and K~ε~ is a constant [19].

Advanced Sensing Modalities

For more complex physiological measurements, advanced FBG configurations have been developed. Cladding-etched fibers can be used to measure the refractive index of the surrounding medium since the standard FBG itself is not inherently sensitive to the refractive index of its environment [19]. These sensors are based on increased evanescent field interaction with the measurand and have found implementations in chemical and biological fields to measure various liquids and gases [19].

During cladding etching, higher-order Bragg resonances appear when the fiber diameter reduces. These higher-order Bragg resonances are used to determine the diameter of a standard optical fiber with a precision of approximately 200 nm. The evanescent field values of the fundamental mode and higher-order modes are affected by the surrounding refractive index to different extents. Using the relative wavelength shifts between the modes, the refractive index of external media can be determined, enabling precise biochemical sensing applications [19].

FBG Sensors in Physiological Monitoring: Applications and Data

The application of FBG sensors in physiological monitoring has expanded significantly due to their unique advantages, including immunity to electromagnetic interference, small size, and ability to perform multipoint sensing while maintaining a compact form factor [20]. Recent advances using chalcogenide and other specialty fibres represent a substantial step towards all-fibre wearable devices for healthcare monitoring [20].

Table 1: Physiological Parameters Monitored Using FBG Sensors

| Physiological Parameter | FBG Sensing Approach | Typical Wavelength Shift Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Temperature | Direct temperature-strain coupling | ~10 pm/°C | Core body temperature monitoring, febrile condition detection [20] [11] |

| Respiratory Rate | Chest wall movement detection | Varies with breathing depth | Sleep apnea monitoring, respiratory disorder diagnosis [20] [11] |

| Heart Rate | Ballistocardiographic movements | Micro-strain measurements | Cardiovascular health assessment, exercise physiology [20] [11] |

| Sweat Analysis | pH-sensitive coatings | Coating-dependent shifts | Metabolic monitoring, dehydration assessment [20] |

| Biomechanical Forces | Strain sensing in tissues/joints | Varies with applied force | Rehabilitation monitoring, sports science, prosthetics [11] |

| Blood Pressure | Pulse wave velocity measurement | ~1-5 nm depending on design | Hypertension management, cardiovascular monitoring [20] |

Quantitative Data from Physiological Monitoring Studies

Research studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of FBG sensors in capturing various physiological signals with high precision. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent investigations:

Table 2: Experimental Data from FBG-Based Physiological Monitoring Studies

| Study Focus | Sensor Configuration | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable body temperature monitoring | FBG integrated into textile | Accuracy: ±0.1°C, Resolution: 0.05°C | [20] [11] |

| Respiratory monitoring | Chest belt with FBG | Respiratory rate accuracy: >95% compared to spirometry | [20] [11] |

| Gait analysis | FBG embedded insole | Force resolution: <1N, capable of identifying gait phases | [20] |

| Cardiac monitoring | FBG on chest strap | Heart rate detection accuracy: 98.2% compared to ECG | [20] [11] |

| Joint movement monitoring | FBG integrated into flexible substrate | Angular resolution: <1 degree for knee flexion | [11] |

| Sweat pH monitoring | Hydrogel-coated FBG | pH detection range: 4-8, resolution: ±0.2 pH units | [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Physiological Signal Acquisition

Protocol 1: Respiratory Rate Monitoring Using FBG Sensors

Principle: Respiratory activity causes thoracic movements that induce strain on an FBG sensor integrated into a chest strap. The resulting wavelength shifts correspond to inhalation and exhalation cycles [20] [11].

Materials:

- FBG sensor (central wavelength: 1530-1560 nm)

- Optical interrogator system (resolution: ≥1 pm)

- Elastic chest strap material

- Medical-grade adhesive for sensor fixation

- Data acquisition software

- Reference spirometer for validation (optional)

Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: Characterize the FBG sensor's baseline spectrum and strain sensitivity prior to integration.

- Chest Strap Integration: Securely mount the FBG sensor onto an elastic chest strap, ensuring the fiber is oriented to maximize strain detection during chest expansion.

- Calibration: Apply known strains to the sensor-chest strap assembly and record corresponding wavelength shifts to establish a strain-wavelength correlation.

- Subject Application: Fit the chest strap snugly around the subject's chest at the level of the xiphoid process.

- Data Acquisition: Connect the FBG to the interrogator and initiate continuous wavelength monitoring at a sampling rate ≥10 Hz.

- Signal Processing: Apply a bandpass filter (0.1-0.5 Hz) to isolate respiratory movements from other artifacts.

- Rate Calculation: Implement peak detection algorithms to identify inhalation peaks and compute respiratory rate in breaths per minute.

Validation: Compare FBG-derived respiratory rates with simultaneous spirometer recordings or manual counting for accuracy assessment. Studies have reported >95% accuracy compared to reference methods [20] [11].

Protocol 2: FBG-Based Body Temperature Monitoring

Principle: FBGs exhibit temperature-dependent wavelength shifts due to thermo-optic and thermal expansion effects, enabling precise body temperature monitoring [20] [11].

Materials:

- FBG sensor with temperature sensitivity ~10 pm/°C

- Optical interrogator with pm-level resolution

- Thermal adhesive or patch for skin attachment

- Reference thermistor or clinical thermometer

- Temperature-controlled calibration chamber

Procedure:

- Temperature Calibration: Characterize the FBG's temperature response by placing it in a controlled thermal chamber across a physiological range (35-41°C).

- Sensor Attachment: Affix the FBG sensor to the skin surface using a medical-grade adhesive patch, ensuring good thermal contact.

- Thermal Isolation: Implement measures to minimize ambient temperature influences, such as using insulating layers.

- Data Collection: Monitor wavelength shifts continuously at a sampling rate of 1 Hz.

- Temperature Conversion: Convert wavelength shifts to temperature values using the established calibration curve.

- Signal Validation: Periodically compare FBG readings with reference clinical thermometers.

Applications: Continuous core temperature monitoring during surgical procedures, febrile illness tracking, and sports physiology studies [20] [11].

Visualization of FBG Sensing Principles

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working principle of an FBG sensor and how it transduces physiological signals into measurable wavelength shifts:

Diagram 1: FBG Sensing Principle. Physiological stimuli induce measurable shifts in the Bragg wavelength.

The signal processing workflow for extracting physiological information from raw FBG signals involves multiple stages of processing and analysis:

Diagram 2: Signal Processing Workflow. Multiple processing stages transform raw wavelength shifts into physiological parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of FBG-based physiological monitoring requires specific materials and reagents optimized for biomedical applications. The following table details essential components:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FBG Physiological Sensing

| Item | Specifications | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| FBG Sensors | Single-mode optical fiber, λ~B~: 1530-1560 nm, reflectivity: >70% | Core sensing element detecting physiological parameters | All physiological monitoring applications [19] [11] |

| Interrogation System | Resolution: ≤1 pm, sampling rate: ≥100 Hz | Precise measurement of Bragg wavelength shifts | High-frequency physiological signal acquisition [19] [20] |

| Biocompatible Coatings | Medical-grade silicone, polyimide, or hydrogel polymers | Protect sensor and enhance biocompatibility for skin contact | Wearable sensors, implantable devices [20] [11] |

| Specialized Functional Coatings | pH-sensitive hydrogels, thermoresponsive polymers | Transduce specific biochemical parameters into mechanical strain | Sweat pH monitoring, metabolite detection [20] |

| Optical Connectors | FC/APC, LC/APC angled physical contact | Ensure low-loss connections between sensor and interrogator | All FBG sensing setups requiring disconnection [21] |

| Packaging Materials | Flexible substrates, composite materials | Protect fragile fiber and facilitate integration into wearables | Smart textiles, wearable monitoring devices [20] [21] |

| Calibration Equipment | Temperature chambers, precision translation stages, reference sensors | Establish accurate relationship between wavelength shift and physiological parameter | Sensor characterization and validation [22] [21] |

The Bragg wavelength shift represents a fundamental mechanism that enables precise quantification of physiological signals using FBG sensors. The direct relationship between external stimuli and measurable wavelength changes provides researchers with a powerful tool for non-invasive monitoring of vital signs, biochemical parameters, and biomechanical functions. As FBG technology continues to evolve, with advancements in specialty fibers, miniaturized interrogation systems, and biocompatible packaging, these sensors are poised to play an increasingly significant role in both clinical research and therapeutic monitoring applications. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this document provide a foundation for researchers to leverage FBG technology in their physiological monitoring investigations, potentially leading to innovative approaches in drug development, personalized medicine, and healthcare diagnostics.

Methodological Innovations and Cutting-Edge Applications in Physiological Monitoring

Fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors represent a advanced sensing technology within optical fiber systems, capable of precise physiological parameter detection. Their fundamental operation relies on the Bragg wavelength shift caused by changes in strain and temperature, described by the equation ΔλB = 2 * [(∂neff/∂T)ΔT + neff(∂Λ/∂ε)Δε] [19]. This principle enables their function as highly sensitive physiological monitors when integrated into textile substrates.

FBG sensors are particularly suited for wearable applications due to their passive operation, immunity to electromagnetic interference (ensuring MRI compatibility), biocompatibility, and multiplexing capability allowing multiple sensing points on a single fiber [23] [24]. This protocol details methodologies for embedding FBG sensors into textiles for monitoring cardiorespiratory parameters, supporting research in continuous health assessment, drug response evaluation, and clinical diagnostics.

FBG Sensing Principles and Textile Integration Approaches

Fundamental FBG Operating Mechanism

FBGs consist of a periodic modulation of the refractive index within the core of a photosensitive optical fiber. When broadband light propagates through the fiber, a specific wavelength, the Bragg wavelength (λB), is reflected back according to the condition λB = 2neffΛ, where neff is the effective refractive index of the fiber core and Λ is the grating period [19] [23]. External stimuli such as mechanical strain from chest wall movement or temperature variations from blood flow or skin contact alter both neff and Λ, resulting in a measurable shift in λB that is linearly proportional to the applied stimulus [19].

Textile Integration Methodologies

Multiple approaches exist for incorporating FBGs into wearable textile platforms, each offering distinct advantages for specific monitoring applications:

- Embedded Yarn Integration: Optical fibers containing FBG arrays are woven or knitted directly into the textile structure during manufacturing, providing excellent mechanical coupling and durability through interlacing with conventional yarns [25] [24]. This method is particularly suitable for respiratory monitoring belts requiring precise strain transmission.

- Surface Attachment: Fibers are attached to finished textiles using biocompatible adhesives or thin polymer encapsulation strips (e.g., PDMS). This approach offers flexibility in sensor placement on existing garments but may present challenges for long-term mechanical stability [26].

- Encapsulated Module Integration: FBG sensors are first embedded within a protective polymer structure (e.g., 3D-printed TPU insoles or flexible silicone patches) which is then attached to the textile. This method provides enhanced strain transfer and protection from bending losses, crucial for footwear applications and localized pressure sensing [26].

Table 1: Comparison of FBG Integration Methods for Wearable Textiles

| Integration Method | Mechanical Coupling | Durability | Comfort/Flexibility | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embedded Yarn | Excellent | High | Moderate | Respiratory belts, chest bands |

| Surface Attachment | Moderate | Moderate | High | Cardiac vests, temperature sensing |

| Encapsulated Module | Excellent | Very High | Low-Moderate | Instrumented insoles, joint sensing |

Experimental Protocols for Vital Sign Monitoring

Multi-Point Respiratory Pattern Monitoring

Principle and Setup

Respiratory monitoring utilizes FBG sensors to detect thoraco-abdominal strain caused by breathing movements. The protocol involves a sensor array positioned to capture compartmental contributions (pulmonary rib cage, abdominal rib cage, and abdomen) to tidal volume [24]. A minimum of three sensing points per compartment is recommended for comprehensive analysis.

Materials and Sensor Fabrication

- FBG Array: 40 FBGs inscribed in a single Boron-doped photosensitive single-mode fiber (PS1250/1500) using a phase mask technique with a Nd:YAG laser (266 nm wavelength) [26] [24].

- Interrogation System: Portable spectrometer with broadband light source (1520-1620 nm range), minimum 1 pm wavelength resolution, and 100 Hz sampling rate [24].

- Textile Platform: Elastic belt or harness composed of two-layer construction with inner moisture-wicking layer and outer structural layer.

- Embedding Process: Optical fiber is routed through specially designed grooves in the textile structure using a PTFE capillary tube filled with PDMS resin for enhanced strain transfer and mechanical protection [26].

Data Acquisition and Processing

- Signal Acquisition: Collect reflected wavelength data from all FBG sensors simultaneously using wavelength division multiplexing (WDM).

- Motion Artifact Compensation: Implement differential measurements between sensors subject to respiratory strain and reference sensors isolated from breathing movements.

- Parameter Extraction:

- Breathing Rate (BR): Calculate from frequency domain analysis (FFT) of wavelength shift time series.

- Tidal Volume Estimation: Correlate summed wavelength shifts from all sensors with spirometer measurements using subject-specific calibration curves.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental setup and data processing pathway for respiratory monitoring:

Cardiac Monitoring via Ballistocardiography and Pulse Wave Detection

Principle and Setup

Cardiac monitoring employs FBGs to detect micro-vibrations and arterial pulsations associated with the cardiac cycle through ballistocardiographic (BCG) and photoplethysmographic (PPG) principles. Sensors are strategically positioned over major arteries (carotid, radial) or integrated into garments covering the chest region to capture mechanical cardiac signals [27] [23].

Materials and Sensor Configuration

- High-Sensitivity FBG Sensors: Chirped FBGs or tilted FBGs with enhanced pressure sensitivity, inscribed using femtosecond laser for improved stability [23].

- Interrogation System: High-speed interrogator with 1 kHz minimum sampling rate and 0.5 pm wavelength resolution to capture rapid pulse waveforms.

- Textile Integration: Direct embedding in form-fitting garments (chest straps, shirt cuffs) using elastic yarns to maintain consistent sensor-skin contact pressure (5-15 mmHg optimal range).

Signal Processing and Parameter Extraction

- Noise Filtering: Implement bandpass filter (0.5-20 Hz) to remove respiratory interference and high-frequency noise.

- Pulse Wave Analysis:

- Heart Rate (HR): Determine from inter-peak intervals in BCG or pulse waveform.

- Heart Rate Variability (HRV): Calculate from time-domain (SDNN, RMSSD) or frequency-domain (LF, HF power) analysis of RR intervals.

- Pulse Transit Time (PTT): Measure using synchronized sensors at proximal and distal sites for blood pressure estimation [24].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of FBG-Based Vital Sign Monitoring

| Vital Parameter | Measured Signal | FBG Sensitivity | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Rate | Thoraco-abdominal strain | 1 pm/με [19] | >94% vs. reference [28] | Compartmental breathing analysis |

| Tidal Volume | Chest wall expansion | Linear correlation R²=0.904 [26] | Requires individual calibration | Non-restrictive monitoring |

| Heart Rate | BCG/Pulse waveform | 0.11 ± 0.10 pm/N [26] | ±2 BPM in controlled conditions | MRI compatibility |

| Blood Pressure | Pulse transit time | N/A | Under investigation | Cuff-less continuous estimation |

Research Reagent and Material Solutions

Successful implementation of FBG-based wearable monitoring systems requires specific materials and instrumentation as detailed below:

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for FBG-Textile Development

| Component | Specification/Recommended Type | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Fiber | Boron-doped photosensitive single mode fiber (e.g., Fibercore PS1250/1500) [26] | FBG inscription substrate with high photosensitivity |

| Phase Masks | Custom period for desired Bragg wavelength (e.g., 1520-1620 nm range) [26] | Pattern definition during FBG fabrication |

| Laser Source | Nd:YAG (266 nm) or femtosecond IR laser for inscription [26] | Inducing periodic refractive index modulation |

| Interrogator | Portable spectrometer with 1 pm resolution, 100+ Hz rate [24] | Wavelength shift detection and recording |

| Textile Substrate | Elastic yarns with low stress relaxation (e.g., spandex blends) [25] | Mechanical support and user comfort |

| Encapsulant | PDMS or TPU for flexible protection [26] | Strain transfer enhancement and fiber protection |

| Adhesive | Biocompatible silicone medical adhesive [26] | Sensor fixation to textile or skin |

Data Interpretation and Analytical Considerations

Signal Validation and Artifact Management

Physiological monitoring in ambulatory environments introduces motion artifacts that require specialized processing approaches. Multi-sensor correlation techniques validate physiological signals by comparing outputs from collocated sensors. Adaptive filtering algorithms effectively separate respiratory and cardiac signals when they occupy overlapping frequency bands [23]. Temperature compensation is critical for accurate strain measurement, achieved through reference FBGs isolated from mechanical deformation but exposed to same thermal environment [19].

Clinical Parameter Correlation

Establishing correlation between FBG sensor outputs and clinical gold standards requires systematic validation protocols. For respiratory monitoring, parallel measurement with pneumotachograph or spirometer generates calibration curves for tidal volume estimation [24]. Cardiac parameter validation utilizes ECG for heart rate timing reference and tonometric arterial pressure for pulse wave analysis verification. Statistical analysis should report correlation coefficients, Bland-Altman limits of agreement, and clinical error grids where appropriate.

The following diagram illustrates the signal processing pathway for extracting cardiac parameters:

The integration of FBG sensors into wearable textiles provides a sophisticated methodology for continuous, unobtrusive monitoring of cardiorespiratory function. The protocols detailed herein enable researchers to develop robust monitoring systems capable of capturing both respiratory patterns and cardiac activity with high precision. As this technology advances, future developments will focus on miniaturized interrogation systems, advanced multi-sensor fusion algorithms, and standardized validation frameworks to transition these capabilities from research environments to clinical practice and commercial healthcare applications.

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors are becoming an increasingly transformative technology in the field of physiological monitoring, particularly for quantifying body motion and kinematics. An FBG is a periodic or aperiodic perturbation of the effective refractive index in the core of an optical fiber, typically written using ultraviolet laser light [29] [7]. When broadband light is transmitted through the fiber, the grating reflects a very narrow band of wavelengths, known as the Bragg wavelength (( \lambdaB )), while transmitting all others. The fundamental principle governing this reflection is expressed by the equation ( \lambdaB = 2n{eff}\Lambda ), where ( n{eff} ) is the effective refractive index of the fiber core and ( \Lambda ) is the grating period [30] [31] [32].

The core sensing mechanism relies on the fact that the Bragg wavelength shifts ( (\Delta\lambdaB) ) in direct, linear proportion to physical parameters such as axial strain (( \Delta\varepsilon )) and temperature (( \Delta T )) [30] [31]. This relationship is quantitatively described by the following equation: [ \Delta\lambdaB = \lambdaB [(1-pe)\Delta\varepsilon + (\alpha + \xi)\Delta T] ] Here, ( p_e ) is the photoelastic constant, and ( \alpha ) and ( \xi ) are the thermal expansion and thermo-optic coefficients, respectively [30] [33]. For kinematic sensing, strain induced by body movement is the primary measurand, while temperature variations are often compensated for using reference gratings or specialized packaging designs [34].

FBG sensors offer a unique combination of properties that make them exceptionally suitable for biomedical motion tracking. These include their small size and light weight, inherent immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI), biocompatibility, and chemical inertness [30] [33]. Furthermore, their innate multiplexing capability allows multiple sensors to be inscribed in a single optical fiber and interrogated by a single unit, enabling distributed sensing over long distances and the creation of dense sensing networks for complex kinematic analysis [34] [31] [7].

FBG Sensing Principles and Signal Demodulation

The operational principle of FBG-based kinematic sensing is the transduction of mechanical deformation into a quantifiable wavelength shift. When an FBG sensor is subjected to axial strain due to bending, stretching, or compression, two primary changes occur: the grating period (( \Lambda )) alters, and the effective refractive index (( n_{eff} )) changes via the strain-optic effect [30] [31]. These changes collectively cause a shift in the reflected Bragg wavelength, which is detected and measured.

A critical consideration in practical applications is the phenomenon of cross-sensitivity, where both strain and temperature contribute to the wavelength shift [34] [7]. For accurate kinematic measurements, this cross-sensitivity must be mitigated. Common strategies include:

- Reference Gratings: Using a second, isolated FBG that experiences only temperature changes to provide a compensatory signal [31].

- Temperature-Self Compensating Structures: Special mechanical designs, such as specific packaging methods using materials with tailored thermal expansion properties, that inherently cancel out the temperature effect on the wavelength shift [34].

- Dual-Parameter Sensing Configurations: Employing specialized grating structures (e.g., hybrid FBG/LPG) or specific packaging that allows for the simultaneous and independent resolution of strain and temperature [7].

The process of measuring the wavelength shift, known as demodulation, is performed by an interrogator. For dynamic motion tracking, high-speed interrogation systems are essential to capture rapidly changing signals [30] [35]. The choice of demodulation principle directly influences the sensor's performance characteristics, including its resolution, range, and speed, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Primary Signal Demodulation Principles for FBG Sensors in Motion Tracking

| Demodulation Principle | Working Method | Key Advantages | Typical Applications in Kinematics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Shift Detection | Tracks the central wavelength shift of the reflected spectrum using an Optical Spectrum Analyzer (OSA) or integrated interrogator [34]. | High accuracy and resolution; direct measurement; well-established technology. | Monitoring of quasi-static movements (e.g., posture); gait analysis; bone strain measurement [30] [34]. |

| Intensity-Based Detection | Measures the change in reflected optical power at a fixed laser wavelength [34] [35]. | Simpler and lower-cost interrogation; very high-speed measurement capability. | High-frequency and transient motion capture (e.g., pulsed elongation, vibrations, muscle tremors) [35]. |

| Phase Signal Demodulation | Utilizes interferometric techniques to detect phase changes in the light, which are related to wavelength shift [34]. | Extremely high sensitivity and resolution. | Detection of subtle physiological signals (e.g., respiratory chest wall deformation, fine muscle vibrations) [30]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process from the physical stimulus to data acquisition in an FBG sensing system.

Figure 1: Signal transduction and acquisition workflow in an FBG-based kinematic sensing system.

Application Notes: From Large-Joint to Fine Motor Skills

The application of FBG sensors in motion tracking spans a wide spectrum, from gross movements of large joints to the delicate intricacies of fine motor skills, demonstrating the technology's remarkable versatility.

Large-Joint Movement Tracking

For monitoring large joints such as the knee, hip, and shoulder, FBG sensors are often integrated into wearable bands or directly embedded into textiles. Their primary function is to measure the angle between body segments during activities like walking, running, or cycling [30]. In these applications, sensors are typically mounted on a cantilever beam structure or an elastic substrate. The bending of this structure during joint movement imposes a predictable strain on the FBG, which is directly correlated to the joint angle [34]. This capability is crucial for objective gait analysis in post-stroke rehabilitation, the assessment of prosthetic fit and function, and sports science for analyzing athletic performance and technique [30] [36]. A key advantage in these scenarios is the sensor's EMI immunity, which allows for reliable operation in environments with electrical noise from muscle activity or other medical devices.

Fine Motor Skill and Gesture Recognition

Tracking fine motor skills, particularly of the hand and face, presents a greater challenge due to the complexity and subtlety of the movements. Recent research has successfully engineered wearable FBG sensors embedded in soft, flexible matrices like Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) silicone elastomer for this purpose [36]. These patches are conformable and can be comfortably attached to the finger joints, wrist, or around the mouth. As a finger bends or the wrist pitches, the PDMS patch deforms, transferring strain to the embedded FBG and causing a wavelength shift. Studies have demonstrated the high accuracy of these systems in recognizing intricate gestures, including individual finger bending, wrist pitch, and mouth movements [36]. This technology holds significant promise for developing advanced human-machine interfaces (HMIs), creating personalized communication aids for patients with disabilities, and enabling highly detailed remote monitoring of rehabilitation exercises for conditions like stroke-induced hand impairment [30] [36].

Internal Biomechanical Measurements

Beyond external wearable sensing, FBGs have also shown great potential for in vivo and in vitro biomechanical investigations. Their small size and biocompatibility make them suitable for measuring strain in bones, pressures in orthopedic joints, and stresses in intervertebral discs [30]. In one study, FBG sensors demonstrated feasibility for assessing bone strain in human cadaver femurs under in vitro loading conditions, offering a novel approach that competes with conventional electrical strain gauges while offering advantages in terms of long-term biocompatibility and application on irregular surfaces [30]. Another application involves understanding the effect of bone calcium loss on mechanical strain response, providing a direct indication of bone health and integrity [30].

The quantitative performance of FBG sensors across these diverse applications is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of FBG Sensors in Various Kinematic Applications

| Application Domain | Measured Parameter | Reported Performance / Range | Key Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Joint Gait Analysis [30] [34] | Knee/Hip/Ankle Angle | Sensitivity: 36 pm/mm (in a specific cantilever setup) [34] | Linearity is crucial for accurate angle calculation; cross-sensitivity to temperature must be managed. |

| Fine Motor Skills (Hand) [36] | Finger Bend, Wrist Pitch | High recognition accuracy across participants post-calibration; Bragg wavelength shift tracked with < 0.5 pm resolution [36]. | PDMS embedding enhances sensitivity and flexibility; system allows for real-time monitoring. |

| Bone Biomechanics [30] | Bone Surface Strain | Measured strain response to loads from 0.1 kg to 4 kg in a three-point bending test. | FBGs can detect increased strain from decalcification, indicating bone quality degradation. |

| Pulsed/High-Speed Elongation [35] | Dynamic Deformation Rate | Strain sensitivity coefficient ( k_{BE} \approx 1.2 \times 10^{-3} ) nm/με at ~1550 nm [35]. | Requires high-speed interrogators or intensity-based detection for microsecond-scale events. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing FBG sensors in two key kinematic tracking scenarios: monitoring wrist pitch for large-joint analysis and finger bending for fine motor skill assessment.

Protocol 1: Wrist Pitch Recognition using a PDMS-Embedded FBG Sensor

This protocol outlines the procedure for fabricating a flexible FBG sensor and utilizing it for non-invasive, accurate wrist pitch measurement, suitable for rehabilitation monitoring [36].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Fabricating a Flexible FBG Sensor

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Single-Mode Optical Fiber (e.g., Corning SMF-28e) | The base medium into which the FBG is inscribed; typically has a cladding diameter of 125 μm [36]. |

| UV Laser & Phase Mask | Equipment for inscribing the periodic grating structure into the fiber core via the photomask technique [36] [7]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Sylgard 184 | A two-part silicone elastomer used to embed the FBG, providing flexibility, skin compliance, and mechanical protection [36]. |

| 3D-Printed Mold (e.g., Resin) | Defines the geometry (length: 40 mm, width: 20 mm, thickness: 1-3 mm) of the final flexible sensor patch [36]. |

| Optical Interrogator (e.g., FS22SI) | Measures the Bragg wavelength shift with high resolution (< 0.5 pm) and stability (1 pm) [36]. |

| Adhesive (e.g., Blu-Tack, Skin-Safe Tape) | Temporarily secures the fiber in the mold during fabrication and affixes the final sensor to the skin. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- FBG Inscription and Preparation: Inscribe an FBG with a Bragg wavelength of approximately 1550 nm and a length of 10 mm into a single-mode optical fiber using the phase mask technique and ultraviolet laser light. Re-coat the bare grating region with acrylate to ensure mechanical strength [36].

- Sensor Fabrication and Embedding:

- Design and 3D-print a mold with the desired patch dimensions (e.g., 40 mm x 20 mm x 2 mm) and integrated guide channels at both ends.

- Secure the FBG fiber straight along the center of the mold using an adhesive, ensuring the grating is positioned in the middle of the mold cavity.

- Mix the PDMS precursor and curing agent at the recommended weight ratio (e.g., 10:1), degas to remove air bubbles, and carefully pour it into the mold.

- Cure the PDMS for 72 hours at room temperature. After polymerization, demold the flexible FBG sensor patch [36].

- Sensor Characterization:

- Connect the sensor to an optical interrogator and record the baseline Bragg wavelength.

- Perform a thermal characterization test (e.g., from 30°C to 70°C) to determine the sensor's thermal responsivity, which is essential for data interpretation [36].

- Perform a mechanical calibration by subjecting the sensor to known bending radii or angles and recording the corresponding wavelength shifts to establish a strain/angle-to-wavelength calibration curve.

- Subject Preparation and Sensor Placement:

- Obtain ethical approval and informed consent from the participant.

- Clean the skin area on the dorsal side of the forearm, crossing the wrist joint.

- Affix the PDMS-embedded FBG sensor securely over the wrist joint using skin-safe double-sided tape or a lightweight strap, ensuring good contact without restricting movement.

- Data Acquisition and Wrist Pitch Recognition:

- Instruct the participant to perform a series of controlled wrist flexion and extension movements through a predefined range of motion (e.g., -90° to +90°).

- Simultaneously, record the Bragg wavelength shift from the interrogator at a sufficient sampling rate (e.g., ≥ 1 Hz).

- Use the pre-established calibration curve to convert the recorded wavelength data into real-time wrist pitch angles.

The experimental workflow for this protocol is detailed below.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for wrist pitch recognition using a PDMS-embedded FBG sensor.

Protocol 2: Finger Bend Tracking for Fine Motor Skill Assessment

This protocol describes the setup for monitoring finger flexion, which is critical for assessing rehabilitation progress in patients with hand motor impairments [33] [36].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

- Flexible FBG Sensor Array: Multiple PDMS-embedded FBG sensors (as fabricated in Protocol 1), ideally with varying thicknesses to optimize sensitivity, arranged in an array.

- Glove Substrate: A lightweight, form-fitting fabric glove to which the sensor array will be attached.

- High-Speed Interrogator: An interrogation system capable of simultaneously reading multiple FBGs with a sampling rate sufficient to capture dynamic finger motion (≥ 10 Hz).

- Data Acquisition and Processing Software: Custom or commercial software for recording, visualizing, and processing the multi-channel wavelength data.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sensor Array Configuration: Fabricate multiple flexible FBG sensors. Plan their placement on the glove to correspond to the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the fingers to be monitored.

- Glove Integration: Secively attach each flexible FBG sensor to the dorsal side of the glove fabric using a flexible, non-reactive adhesive. Ensure the sensors are aligned to bend with the finger joints and that the optical fiber leads are routed to minimize stress concentrations.

- System Calibration:

- Have the participant wear the instrumented glove.

- For each finger joint, record the Bragg wavelength at known flexion angles (e.g., 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°) using a goniometer as a reference.

- Generate a unique calibration curve (wavelength shift vs. flexion angle) for each sensor in the array.

- Data Collection and Gesture Recognition:

- Instruct the participant to perform a series of tasks, from isolated finger bending to complex gestures (e.g., making a fist, pinching, or tracing shapes).

- Record the wavelength data from all sensors simultaneously throughout the tasks.

- Apply the calibration curves to convert the multi-channel data into a real-time time series of joint angles.

- For gesture recognition, the combined angle data from multiple sensors can be fed into a classification algorithm (e.g., a machine learning model) to identify specific hand postures or movement patterns.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of FBG-based kinematic tracking systems relies on a set of core components and materials. The following table details these essential items and their functions within the research setup.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for FBG Kinematic Sensing

| Category / Item | Specific Function / Relevance to Research |

|---|---|

| Optical Fiber & Gratings | |

| Single-Mode Optical Fiber (SMF) | Standard medium for FBG inscription; provides a single light propagation path for clear signal interpretation [36] [7]. |

| Photosensitive Fiber (e.g., Germanosilicate) | Fiber type with enhanced photosensitivity, facilitating efficient FBG inscription with ultraviolet light [29] [7]. |

| Fabrication & Inscription | |

| Ultraviolet (UV) Laser Source | Provides high-energy light required to permanently modify the refractive index of the fiber core and inscribe the grating [29] [7]. |

| Phase Mask | A photolithographic mask placed between the laser and fiber to create the specific interference pattern needed for periodic grating inscription [36] [7]. |

| Sensor Packaging & Substrates | |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | A flexible, biocompatible silicone elastomer used to embed and protect FBGs, enhancing their durability, sensitivity to bending, and skin compliance [36]. |

| Polyimide Coating | A thin, tough polymer coating often applied directly to FBGs to protect them from moisture and mechanical damage while allowing for good strain transfer [30]. |

| Cantilever Beam Structures | A simple elastic mechanical structure used in many displacement sensors to convert linear displacement into a uniform strain on the surface-mounted FBG [34]. |

| Interrogation & Data Acquisition | |

| Optical Spectrum Analyzer (OSA) | Instrument used in laboratory settings to directly visualize and measure the reflection spectrum and wavelength shift from an FBG [30] [34]. |

| Commercial FBG Interrogator | A compact, integrated system that includes a broadband light source and a spectrometer, designed specifically for high-resolution, multi-channel FBG reading [36]. |

| Calibration & Testing | |

| Temperature Chamber (e.g., Heating Station) | Essential for characterizing the thermal responsivity of the FBG sensor and for developing temperature compensation strategies [36]. |

| Mechanical Testing Machine | Used for precise mechanical calibration of sensors by applying known loads or displacements [30]. |

Fiber Bragg Grating technology presents a powerful and versatile solution for the detailed quantification of human movement, seamlessly spanning the measurement of large-joint kinematics to the fine nuances of hand and finger motor control. The intrinsic properties of FBGs—including their small size, EMI immunity, biocompatibility, and multiplexing capability—make them uniquely suited for both research and clinical environments. As demonstrated in the provided application notes and protocols, the integration of FBGs with advanced flexible materials like PDMS is paving the way for a new generation of wearable, unobtrusive, and high-fidelity motion capture systems. The ongoing development of more sensitive, robust, and cost-effective FBG-based sensing systems holds the promise of revolutionizing fields such as rehabilitation science, sports medicine, neurology, and drug development, where objective, precise, and continuous monitoring of motor function is paramount.

FBG-Based Catheter Systems for Minimally Invasive Diagnostics and Force Sensing

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors represent a transformative technology in the field of minimally invasive surgery (MIS), enabling precise force sensing capabilities that are critical for patient safety and procedural success. These sensors operate on the principle of wavelength shift detection in response to mechanical strain, offering inherent advantages such as electromagnetic immunity, miniaturization, and high sensitivity [7]. Their integration into catheter systems addresses a fundamental challenge in interventional procedures: the lack of tactile feedback at the instrument-tissue interface. Without this feedback, surgeons risk applying inadequate or excessive force, potentially leading to tissue damage, perforation, or ineffective treatment [37]. The clinical significance of this technology is particularly evident in cardiac ablation procedures, where studies have demonstrated that contact forces between 0.1–0.4 N are essential for effective ablation, with deviations from this range potentially resulting in complications such as cardiac perforation or insufficient scarring of cardiac tissue [38].

This document provides comprehensive application notes and experimental protocols for FBG-based catheter systems, specifically designed for researchers and developers working in physiological monitoring and medical device innovation. The content encompasses working principles, performance characterization across various implementations, detailed methodologies for sensor integration and validation, and essential research tools required for advancing this technology toward clinical translation.

Working Principle and Sensing Mechanisms