Clinical Validation of Bio-Optical Cancer Diagnostics: A Roadmap for Biomarker Translation and Regulatory Success

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the clinical validation of bio-optical cancer diagnostics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Clinical Validation of Bio-Optical Cancer Diagnostics: A Roadmap for Biomarker Translation and Regulatory Success

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the clinical validation of bio-optical cancer diagnostics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of optical technologies like genome mapping, details rigorous methodological validation protocols integrating AI and multi-omics, and addresses key troubleshooting challenges in translational workflows. Furthermore, it offers a comparative analysis against standard cytogenetic techniques, synthesizing evidence to guide robust assay development, regulatory submission, and successful clinical implementation for precision oncology.

The Foundation of Bio-Optics in Oncology: From Light-Based Imaging to Clinical Insights

Bio-optics represents the innovative convergence of photonics—the science of light generation, detection, and manipulation—with biology and medicine. This dynamic field employs light-based technologies to analyze and manipulate biological materials, creating powerful tools for research and clinical diagnostics. A core application of biophotonics is in the realm of cancer detection and characterization, where technologies like optical genome mapping (OGM) and advanced imaging systems provide unprecedented insights into genetic and cellular abnormalities. These approaches leverage the unique properties of light, including non-contact measurement, high sensitivity, and real-time data acquisition, to reveal pathological changes without invasive procedures [1]. The field is rapidly evolving beyond traditional cytogenetic techniques, offering researchers and clinicians the ability to detect structural variations in the genome and visualize tissue abnormalities with resolution that far exceeds conventional methods.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of optical genome mapping against established cytogenetic techniques, detailing its experimental validation, technical workflows, and growing role in cancer research. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding the capabilities and limitations of these technologies is crucial for selecting appropriate methods for genomic analysis and clinical study design.

Optical Genome Mapping: Technology and Workflow

Fundamental Principles

Optical genome mapping is a high-resolution cytogenomic technique that enables genome-wide detection of balanced and unbalanced structural variations using ultra-high molecular weight (UHMW) DNA. Unlike sequencing-based approaches that determine nucleotide order, OGM visualizes long DNA molecules to identify structural variations based on fluorescent labeling patterns. The technology utilizes specific sequences—CTTAAG hexamer motifs—as labeling sites, creating a genome-wide density of approximately 14-17 labels per 100 kb that serves as a unique "barcode" for each genomic region [2]. These patterns allow for direct comparison against a reference genome, enabling detection of deletions, duplications, insertions, translocations, and inversions without requiring cell culture or prior knowledge of the genome's structure [3].

The resolution and detection capabilities of OGM significantly surpass traditional cytogenetic methods. While chromosomal banding analysis typically resolves abnormalities larger than 5-10 Mb, and FISH can detect variations of 60 kb-1 Mb, OGM reliably identifies structural variations down to 500 bp in size, depending on the analysis pipeline and coverage depth [3] [2]. This resolution, combined with its ability to span complex repetitive regions that challenge short-read sequencing technologies, positions OGM as a powerful tool for uncovering previously cryptic genomic rearrangements in cancer research.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Implementing OGM requires strict adherence to specific protocols to preserve DNA integrity and ensure data quality:

DNA Extraction: Isolation of UHMW DNA is critical and utilizes a specialized paramagnetic disk-based protocol designed to minimize shearing forces. This method routinely yields DNA fragments averaging >230 kb in size, substantially longer than conventional extraction techniques [4] [2]. The process requires viable cells that cannot be previously fixed, which can be frozen for future use.

Fluorescent Labeling: Extracted DNA is fluorescently labeled at the specific CTTAAG recognition motifs. This is achieved through a covalent modification process that labels the DNA without digesting it, creating the unique pattern of fluorescent tags that serves as the barcode for subsequent analysis [3] [2].

Linearization and Imaging: Labeled DNA molecules are loaded into nanochannel arrays on silicon chips, where they become linearized. As each molecule passes through the channels, high-resolution imaging systems capture the fluorescent label patterns. Current instrumentation can generate up to 5000 Gbp of raw data per flow cell, enabling theoretical genome coverage up to 1250× [2].

Data Analysis: Specialized algorithms convert the captured images into digitalized molecule maps. These are assembled and compared to an in silico reference genome. Two primary analysis pipelines are employed:

- De novo Assembly: Typically used for germline (constitutional) analysis at >80× coverage (>400 Gbp data)

- Rare Variant Analysis (RVP): Used for somatic studies (e.g., cancer) with sensitivity down to ~5% variant allele fraction at >340× coverage (>1500 Gbp data) [2].

The entire workflow, from DNA extraction to final analysis, requires approximately four days, with the majority of time dedicated to automated imaging and computational analysis [2].

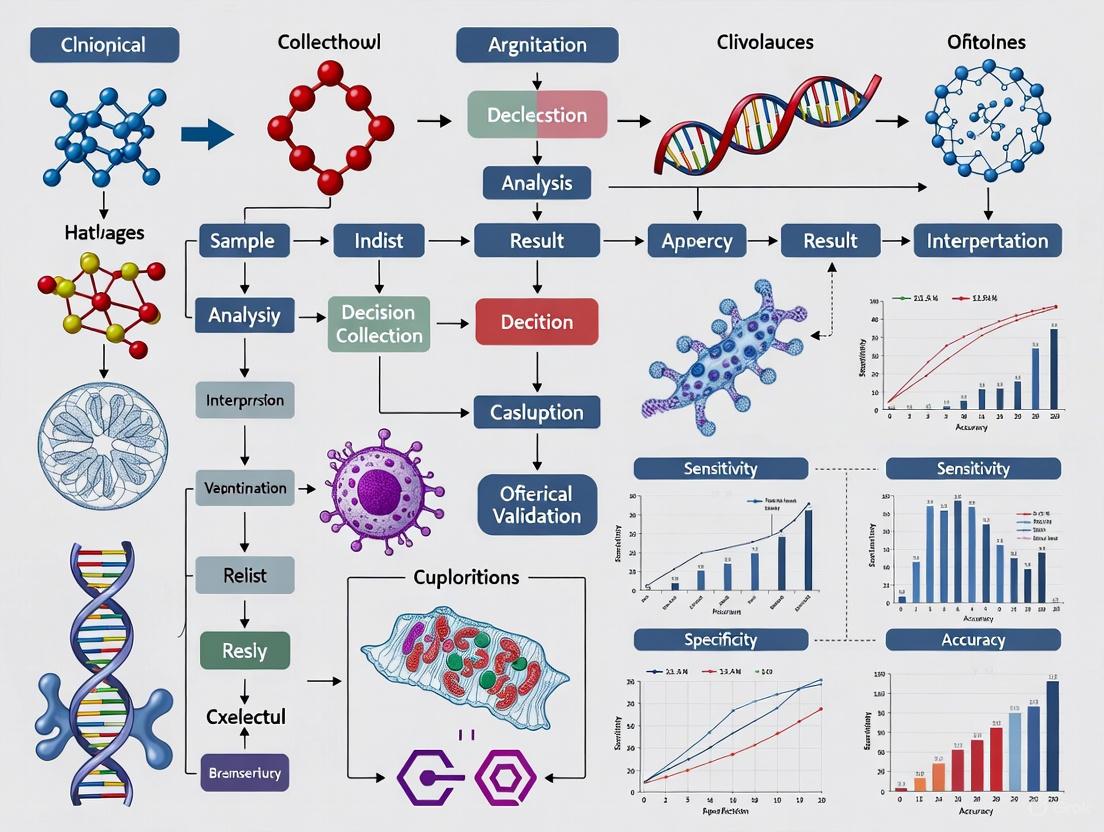

OGM Experimental Workflow: The process from sample preparation to data analysis, highlighting key steps requiring specialized reagents and equipment.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Detection Capabilities Across Cytogenetic Platforms

The selection of cytogenetic testing methodology significantly impacts the types and sizes of genomic abnormalities detectable in cancer genomics research. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of OGM against established techniques.

Table 1: Technology Comparison for Structural Variant Detection in Cancer Genomics

| Methodology | Resolution | SV Types Detected | Limit of Detection | Genome-Wide | Balanced SV Detection | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-Banded Chromosome Analysis | 5-10 Mb | CNV, SV | ~10% (single cell) | Yes | Limited | Poor resolution, requires cell culture |

| Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) | 60 kb - 1 Mb | CNV, SV | ~2-5% (single cell) | Targeted only | Limited | Targeted approach, genome blind spots |

| Chromosomal Microarray (CMA) | 25 kb | CNV, AOH* | ~10-15% (bulk) | Yes | No | Cannot detect balanced rearrangements |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Single nucleotide | SNV, CNV, SV* | ~1-5% (bulk) | Yes* | Yes* | Complex SV detection challenging |

| Optical Genome Mapping (OGM) | 500 bp - 5 kb | CNV, SV, AOH, Repeat expansions | ~5% (bulk) | Yes | Yes | Requires UHMW DNA, not high-throughput |

AOH: Absence of Heterozygosity; *Capabilities vary by NGS approach and bioinformatic pipelines [3] [2]

OGM demonstrates particular strength in resolving complex structural variants (cxSVs), which involve multiple breakpoints and rearrangement types. Research indicates OGM can resolve interspersed duplications up to approximately 550 kb in size by obtaining multiple individual DNA molecules completely spanning the duplicated segment [4]. This capability is critical in cancer genomics, where such complex rearrangements can drive oncogenesis.

Analytical Performance and Validation Data

Clinical validation studies demonstrate OGM's robust performance characteristics. One comprehensive evaluation involving 92 sample runs (including replicates) with 59 hematological neoplasms and 10 controls reported:

- Sensitivity: 98.7%

- Specificity: 100%

- Accuracy: 99.2%

- First-pass technical success rate: 100% [5]

The study determined OGM's limit of detection to be at a 5% allele fraction for aneuploidy, translocation, interstitial deletion, and duplication, making it suitable for detecting minor clones in heterogeneous tumor samples [5]. In reproducibility assessments, OGM demonstrated excellent inter-run, intra-run, and inter-instrument consistency [5].

In a study focusing on multiple myeloma, OGM demonstrated significant clinical utility by either improving genetic diagnosis or detecting additional alterations beyond what was identified by targeted FISH analysis [6]. For hematologic malignancies, research shows OGM identifies clin relevant SVs in 34% of patients that were cytogenetically cryptic, with 17% of cases having findings that would have changed risk assessment [2].

Complementary Bio-Optical Imaging Technologies

Beyond genome mapping, other biophotonic approaches are advancing cancer detection through tissue and cellular imaging:

Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI): This technology captures data across hundreds of narrow wavelengths in addition to visible light, revealing subtle tissue differences based on unique spectral signatures. Researchers are miniaturizing HSI systems for integration with endoscopes to improve real-time detection of gastrointestinal cancers, with the goal of reducing the approximately 10% of GI cancers missed by standard endoscopy [7].

Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) Imaging: This label-free technique leverages Raman scattering to distinguish cancer cells from normal cells based on their vibrational characteristics. Particularly valuable for brain tumor surgery, SRS imaging can visualize lipid droplets in fresh, native condition, potentially enabling intraoperative tumor margin assessment without time-consuming histological processing [8].

PET-enabled Dual-Energy CT: This hybrid imaging innovation combines positron emission tomography (PET) with dual-energy computed tomography (CT). By using PET data to create a second, high-energy CT image, it provides enhanced tissue composition analysis alongside metabolic information, potentially improving differentiation between healthy and cancerous tissues [9].

These imaging modalities complement OGM by providing spatial context in tissues, while OGM offers comprehensive genomic structural information, together creating a multi-scale bio-optical diagnostic toolkit.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing OGM requires specific reagents and materials designed to preserve macromolecular integrity and enable high-resolution analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Optical Genome Mapping

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Specifications | Importance for Assay Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-High Molecular Weight (UHMW) DNA Isolation Kit | Extracts long DNA fragments while minimizing shear | Paramagnetic disk-based purification; average fragment size >230 kb | Foundation of entire assay; shorter fragments reduce genome coverage and SV resolution |

| Direct Labeling and Staining Reagents | Fluorescently labels specific sequence motifs (CTTAAG) | Label density ~14-17 labels/100 kb; covalent binding | Creates unique "barcode" pattern for genome alignment; inconsistent labeling affects variant calling |

| Nanochannel Chips | Linearizes DNA molecules for imaging | Hundreds of thousands of parallel nanochannels | Ensures uniform molecule stretching for accurate label pattern measurement |

| Reference Genome | In silico comparison for variant detection | Species-specific assembled genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human) | Accuracy of structural variant identification depends on reference quality and completeness |

| Data Analysis Software | Identifies structural variants from raw image data | Supports de novo (germline) and rare variant (somatic) pipelines | Critical for sensitivity/specificity; requires appropriate coverage (>80× germline, >340× somatic) |

Optical genome mapping represents a significant advancement in the bio-optical diagnostics landscape, offering researchers a powerful tool for comprehensive structural variant detection. With its high resolution, ability to detect balanced and unbalanced rearrangements in a single assay, and demonstrated superior diagnostic yield compared to traditional cytogenetic methods, OGM addresses critical gaps in cancer genomics research. While the technology requires specialized reagents and bioinformatic support, its capacity to resolve complex genomic architectures provides valuable insights for tumor classification, prognostication, and therapeutic development. As the field progresses, integration of OGM with complementary bio-imaging technologies and sequencing approaches will further enhance our understanding of cancer biology and accelerate the development of targeted treatments.

Cytogenetics, the study of chromosomes and their role in human disease, has long been a cornerstone of genetic diagnostics and cancer research [10]. For over four decades, conventional karyotype analysis has provided a global assessment of chromosomal numerical and structural abnormalities, serving as a powerful view of the entire human genome [11]. However, this established technique represents what many consider a 'scientific art'—requiring extensive training, expertise, and manual interpretation that is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain as skilled cytogeneticists retire [11]. The limitations of these standard approaches have created critical unmet needs in both research and clinical diagnostics, particularly as we enter an era demanding higher resolution, greater efficiency, and more comprehensive genomic assessment.

The field has evolved through several technological revolutions, from classic G-banded karyotyping to molecular cytogenetic techniques like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and more recently to chromosomal microarrays (CMA) [10] [11]. Each advancement has addressed specific limitations while introducing new constraints. Currently, comprehensive analysis of structural variants in hematological malignancies requires a combination of multiple cytogenetic techniques, including karyotyping, FISH, and CNV microarrays [12] [13]. This multi-assay approach is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and costly, creating significant barriers to optimal patient management in oncology and other genetic fields.

This article objectively compares the performance of emerging bio-optical technologies with standard cytogenetic techniques, focusing specifically on Optical Genome Mapping (OGM) as a representative next-generation cytogenomic approach. Through examination of experimental data and validation studies, we demonstrate how these innovative methodologies are addressing the critical limitations that have long constrained conventional cytogenetic analysis.

Limitations of Standard Cytogenetic Techniques

Technical and Resolution Constraints

Conventional cytogenetic techniques face fundamental limitations that impact their diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility. Karyotype analysis, while providing a genome-wide view, has a resolution limit of approximately 5-10 megabases (Mb), preventing detection of smaller but clinically significant structural variations [10] [12]. This technique requires cell culture, which introduces selection bias and fails in 10-40% of cases due to culture failure or microbial contamination [14]. Additionally, karyotyping is labor-intensive, low-throughput, and reliant on highly trained technologists capable of interpreting complex banding patterns [11] [14].

FISH, while offering higher resolution for specific genomic regions, is inherently targeted—requiring prior knowledge of which regions to interrogate [12]. This technique cannot identify novel gene fusions or characterize unknown partner genes in translocations [12]. Furthermore, FISH is labor-intensive, and quality-assured probes are expensive, making comprehensive genome-wide assessment impractical [14]. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) provides high resolution for detecting copy number variations but cannot identify balanced chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations or inversions, which are crucial drivers in many cancers [12].

Diagnostic Gaps in Clinical Practice

The limitations of standard techniques create significant diagnostic gaps in clinical practice. In cancer cytogenetics, 'phenocopies' or 'mimics' present a serious challenge—these appear under the microscope as recurrent oncogenic rearrangements but do not involve the relevant genes [11]. Studies suggest approximately 1% of rearrangements reported as recurrent oncogenic abnormalities may be these non-functional mimics, with potentially serious implications for clinical management [11].

In the analysis of products of conception (POC) for recurrent pregnancy loss, conventional karyotyping fails to provide results in 10-40% of cases due to culture failures [14]. When molecular techniques like multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) are used as alternatives, they cannot characterize balanced structural rearrangements (like Robertsonian translocations) or ploidy changes, which comprise 2.46% of samples (99% confidence interval = 0.09-4.83) [14]. For mesenchymal neoplasms, cytogenetic analysis requires fresh tissue (not frozen or fixed in formalin), creating significant logistical challenges for pathologists who may prematurely place specimens in fixative [15].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Standard Cytogenetic Techniques

| Technique | Resolution Limit | Major Constraints | Failure Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Karyotyping | 5-10 Mb | Culture bias, subjective interpretation, labor-intensive | 10-40% [14] |

| FISH | 50-500 kb | Targeted approach only, cannot identify novel fusions | Varies by sample quality |

| CMA | Few kb | Cannot detect balanced rearrangements | 1-5% |

| MLPA | Varies by probe spacing | Cannot detect balanced rearrangements or ploidy changes | ~1% [14] |

Optical Genome Mapping: An Emerging Solution

Optical Genome Mapping (OGM) represents a paradigm shift in cytogenomic analysis, functioning as what has been termed "next-generation cytogenetics" [12]. This genome-wide technology detects both structural variants (SVs) and copy number variations (CNVs) in a single assay, overcoming the piecemeal approach required by traditional techniques [12]. OGM is based on imaging ultra-long (>150 kbp) high-molecular-weight DNA molecules that are fluorescently labeled at specific sequence motifs [12] [11].

The most common platform currently used for OGM is the Saphyr system from Bionano Genomics [12]. The workflow involves: (1) extracting ultra-high molecular weight DNA from fresh or frozen samples; (2) labeling DNA at specific sequence motifs (CTTAAG) using an enzyme (DLE-1) that achieves a label density of approximately 15 labels per 100 kb; (3) linearizing the labeled DNA molecules in nanochannel arrays; (4) imaging the genome-wide fluorescent pattern; and (5) comparing the results to a reference genome to identify structural variants [12]. Recently, Bionano introduced a direct labeling and staining (DLS) method that shows a 50x improvement in labeling contiguity compared to the DLE-1 enzyme system [12].

Two bioinformatic pipelines are used for data analysis: a rare variant pipeline (RVP) designed to identify variants at low allele frequencies (as low as 5% variant allele frequency), and a de novo assembly approach that can detect smaller SVs (approximately 500 bp) but has lower sensitivity for rare events (15-25% variant allele frequency) [12]. The system provides multiple visualization methods including Circos plots, genome browser views, and whole-genome plots that display copy number, absence of heterozygosity, and variant allele fractions [12].

Advantages Over Conventional Approaches

OGM offers several distinct advantages over the cascade of conventional diagnostic tests. It provides a more rapid, less labor-intensive approach that avoids the need for multiple techniques [12]. Where conventional approaches require a combination of karyotyping, FISH, and CMA to fully characterize genomic alterations—a process taking more than 20 days—OGM can provide comprehensive assessment in approximately one week [12].

The resolution of OGM represents a significant improvement over conventional techniques. While karyotyping has a resolution limit of about 5 Mb, OGM can detect structural variants from 500 bp up to tens of Mb, representing a 100x-20,000x improvement in resolution depending on the variant type and analysis tools used [12]. Unlike CMA, OGM can detect balanced chromosomal rearrangements including translocations and inversions [12]. Furthermore, OGM can identify novel translocations leading to gene disruption or new fusions involving genes that are important drivers of cancer pathogenesis and targeted therapy [12].

OGM is particularly powerful for characterizing complex genomic rearrangements such as chromothripsis and chromoplexy (collectively termed chromoanagenesis), which involve hundreds of genomic rearrangements caused by chromosomal shattering and random reassembly [12]. The technology can also identify additional material in marker chromosomes and define rearrangement breakpoints with precision of a few kilobases [12].

OGM Workflow: From DNA to Variant Detection

Experimental Validation and Performance Comparison

Analytical Performance in Hematological Malignancies

Multiple studies have validated OGM's performance against standard cytogenetic techniques in hematological malignancies. In a comprehensive study of 52 individuals with hematological malignancies, OGM demonstrated excellent concordance with diagnostic standard assays [13]. Samples were divided into simple (<5 aberrations, n=36) and complex (≥5 aberrations, n=16) cases, with OGM reaching an average of 283-fold genome coverage [13].

For the 36 simple cases, OGM detected all clinically reported aberrations identified through standard techniques, including deletions, insertions, inversions, aneuploidies, and translocations [13]. In the 16 complex cases, results were largely concordant between standard-of-care tests and OGM, but OGM often revealed higher complexity than previously recognized [13]. The study reported sensitivity of 100% and a positive predictive value of >80% for OGM compared to standard techniques [13].

Notably, OGM provided a more complete assessment than any single previous test and most likely reported the most accurate underlying genomic architecture for complex translocations, chromoanagenesis, and marker chromosomes [13]. The technology was particularly effective in defining rearrangements involving genes with multiple possible partners, such as KMT2A, MECOM, ETV6, NUP98, or IGHV in hematological malignancies [12]. These rearrangements are typically investigated using FISH with break-apart probes, which cannot identify the partner gene without additional targeted testing [12].

Quantitative Comparison of Technical Parameters

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cytogenetic Techniques

| Parameter | Karyotyping | FISH | CMA | OGM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | 5-10 Mb [12] | 50-500 kb | Few kb [12] | 500 bp-1 Mb [12] |

| SV Detection | All types (≥5 Mb) | Targeted only | None for balanced [12] | All types [12] |

| CNV Detection | ≥5 Mb | Targeted only | Few kb [12] | >500 kb [12] |

| Turnaround Time | 7-14 days | 2-3 days | 7-14 days | ~7 days [12] |

| Success Rate | 60-90% [14] | >95% | >95% | >98% [12] |

| VAF Sensitivity | 10-20% | 5-10% | 10-20% | 5% (RVP) [12] |

Table 3: Detection Capabilities for Specific Variant Types

| Variant Type | Karyotyping | FISH | CMA | OGM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aneuploidy | Yes | Targeted | Yes | Yes [12] |

| Translocations | Yes (≥5 Mb) | Targeted | No | Yes [12] |

| Inversions | Yes (≥5 Mb) | Targeted | No | Yes [12] |

| Microdeletions | No | Targeted | Yes | Yes [12] |

| Marker Chromosomes | Yes | Partial | Partial | Yes [12] |

| Ring Chromosomes | Yes | Partial | Partial | Yes [12] |

| Chromothripsis | Limited | No | Partial | Yes [12] |

| Ploidy Changes | Yes | No | Yes | Limited [12] |

Research Reagent Solutions for OGM Implementation

Successful implementation of OGM requires specific research reagents and materials optimized for the technology. The following table details essential components for establishing OGM in a research setting:

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Genome Mapping

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specification Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-High Molecular Weight DNA Isolation Kits | Extract long DNA strands preserving molecular integrity | Minimum DNA length >150 kbp; minimize double-strand breaks |

| Sequence-Specific Labeling Enzymes | Tag specific genomic motifs for visualization | DLE-1 enzyme targets CTTAAG motifs; new DLS chemistry available |

| Fluorescent Labeling Dyes | Enable detection of labeled DNA molecules | High quantum yield; photostability; compatible with imaging system |

| Nanochannel Chips | Linearize DNA molecules for imaging | Uniform channel size; surface treatments to prevent adhesion |

| Size Standards | Calibrate molecule length measurements | DNA molecules of known length; stable under imaging conditions |

| Reference Genome Databases | Compare sample data against reference | Species-specific; regularly updated; comprehensive variant annotation |

| Bioinformatic Analysis Software | Identify, annotate, and visualize variants | User-friendly interface; clinical-grade validation; customizable filters |

Discussion: Implications for Research and Clinical Applications

The comprehensive data from validation studies demonstrates that OGM effectively addresses the critical unmet needs in conventional cytogenetic techniques. By providing a complete assessment of global genomic alterations in a single assay, OGM represents a significant advancement for both research and potential clinical applications [12] [11] [13]. The technology's ability to detect novel clinically significant structural variants suggests it will contribute to better patient classification, prognostic stratification, and therapeutic choices in hematological malignancies [12].

From a research perspective, OGM enables studies of chromoanagenesis and complex karyotypes with unprecedented resolution [12]. The technology has revealed that submicroscopic structural variants smaller than 5 Mb that overlap critical genes involved in leukemogenesis are highly under-ascertained with current testing [11]. Recent studies estimate that up to 25% of deleterious mutations in the human genome may result from structural variants [11], highlighting the importance of comprehensive detection methods.

For clinical applications, OGM shows potential to replace the multiple techniques currently required for complete cytogenetic assessment [12] [11] [13]. The technology's higher resolution and ability to detect all variant types in a single assay address the major limitations of both conventional and molecular cytogenetic techniques. However, certain limitations remain, including difficulty detecting ploidy changes, copy-number neutral loss of heterozygosity, and variants in centromeric and telomeric regions [12]. Additionally, false positive rearrangements have been reported in some studies, necessitating confirmation of clinically significant findings with orthogonal methods [12].

The future of cytogenetics lies not in abandoning classical approaches but in integrating new technologies that expand our capabilities. As one editorial eloquently stated, "Cytogenetics is a science that deals with the number, structure, and function of chromosomes within the nucleus and the role of chromosome abnormalities in human disease. While the tools we use to assess the structure and function of chromosomes may change, the study of cytogenetics retains its scope and significance" [11]. Optical Genome Mapping and other advanced genomic technologies represent the next evolution in this ongoing scientific journey, promising to unlock new discoveries in basic chromosome biology and clinical disease mechanisms.

Addressing Technical Limitations with OGM Solutions

In the field of bio-optical cancer diagnostics, establishing robust benchmarks for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy is paramount for translating research innovations into clinically validated tools. These metrics form the foundation for evaluating diagnostic performance, guiding regulatory approval, and ultimately building clinical trust. The emergence of sophisticated technologies—from artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced imaging to ultra-sensitive biomarker assays—has necessitated increasingly stringent performance standards to ensure reliable patient outcomes.

Diagnostic markers generally fall into three categories: diagnostic markers that identify tissue of origin or tumor subtype, prognostic markers that estimate disease outcome likelihood, and predictive markers that forecast response to specific therapies [16]. For a marker and its associated assay to be clinically useful, it must meet two critical criteria: it must be measurable by a reliable and widely available assay, and it must provide information about the disease that is meaningful to both physicians and patients [16].

This guide objectively compares the performance of contemporary diagnostic platforms, detailing their experimental protocols and establishing benchmark values essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in cancer diagnostics.

Performance Benchmark Tables for Diagnostic Technologies

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks for AI-Based Optical Diagnostic Systems

| Technology | Clinical Application | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI-OCT (SVM/KNN) [17] | Diabetic Macular Edema (Binary Classification) | Not Reported | Not Reported | 92% | Not Reported |

| niceAI (XAI System) [18] | Colorectal Polyp Classification (Adenomatous vs. Hyperplastic) | 88.8% | 87.9% | 88.3% | 0.946 |

| BlurryScope [19] | Breast Cancer HER2 Scoring (Binary: 0/1+ vs. 2+/3+) | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~90% | Not Reported |

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for Biomarker Assays

| Technology | Clinical Application | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simoa p-Tau 217 [20] | Alzheimer's Amyloid Pathology Detection | >90% | >90% | >90% | Two-cutoff approach |

| UBC Rapid Assay [21] | Bladder Cancer Detection | Variable with cutoff | Variable with cutoff | Variable with cutoff | Optimal cutoff derivation via ROC index |

Table 3: Molecular Methods in Cancer Genetics

| Technique | Key Feature | Representative Application | Detection Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| ddPCR [22] | Quantitative detection of rare alleles | Detection of PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer | MAF < 0.1% |

| RT-PCR [22] | High sensitivity for tissue-specific genes | Detection of circulating breast cancer cells | 10 cells per 3 mL blood |

| Ultra-SEEK [22] | Multiplex detection capability | Cancer mutation panels | MAF ~0.1% |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmark Establishment

AI-Enhanced Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

Objective: To evaluate the performance of AI-based software against conventional clinical assessment of OCT images for diagnosing diabetic macular edema (DME) [17].

Methodology:

- Study Design: Prospective, non-randomized comparative study analyzing 700 OCT exams.

- Feature Vector: 26 features including demographic data (age, sex), eye laterality, visual acuity, and 21 quantitative OCT parameters.

- AI Models: Compared logistic regression, support vector machines (SVM), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), and decision tree models.

- Feature Engineering: Applied paraconsistent feature engineering (PFE) to isolate diagnostically relevant variables.

- Classification Scenarios: Binary (DME presence vs. absence) and multiclass (six distinct DME phenotypes).

Performance Validation: The study used specialist physician diagnosis as the reference standard. In binary classification using all features, SVM and KNN achieved 92% accuracy. When restricted to four PFE-selected features, accuracy declined modestly to 84% for logistic regression and SVM [17].

Explainable AI for Optical Diagnosis in Colonoscopy

Objective: To develop an explainable AI method (niceAI) for classifying hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps that aligns with endoscopists' decision-making processes [18].

Methodology:

- Feature Extraction: Initially identified 2,048 deep features, 93 radiomics features, and color features.

- Feature Selection: Employed multi-step selection using Spearman's correlation analysis:

- First Selection: 103 deep features and 30 radiomics features showed significant correlation (R > 0.5, p < 0.05).

- Second/Third Selection: Compared performance of deep features with NICE feature grading using R² score, identifying optimal combinations (e.g., nine deep features for surface pattern Type 1, six for Type 2).

- Model Integration: Merged selected deep features with narrow-band imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic (NICE) grading.

- Reference Standard: Histopathological diagnosis of hyperplastic versus adenomatous polyps.

Performance Validation: The system achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.946, sensitivity of 0.888, specificity of 0.879, and accuracy of 0.883, meeting SODA (sensitivity > 0.8; specificity > 0.9) and PIVI 2 (negative predictive value > 0.9 for high-confidence images) benchmarks [18].

Digital Immunoassay for Plasma Biomarker Detection

Objective: To analytically and clinically validate a high-accuracy fully automated digital immunoassay for plasma phospho-Tau 217 [20].

Methodology:

- Technology: Single molecule array (Simoa) technology on HD-X instrument, a fully automated digital immunoassay analyzer.

- Assay Principle: 3-step sandwich immunoassay using anti-p-Tau 217 coated paramagnetic capture beads and biotinylated detector antibodies.

- Calibration: Peptide construct with N-terminal epitope and phosphorylated mid-region epitope, with calibrators ranging from 0.002-10.0 pg/mL.

- Study Population: 873 symptomatic individuals from two independent clinical cohorts.

- Reference Standard: Amyloid status determined by PET or cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers.

- Cutoff Strategy: Implemented a 2-cutoff approach with an intermediate "gray zone" (30.9% of samples) to maximize predictive values.

Performance Validation: The assay demonstrated >90% sensitivity, specificity, and agreement with comparator methods for samples outside the intermediate zone, meeting Alzheimer's Association recommended accuracy of ≥90% for diagnostic use [20].

Compact AI-Powered Microscopy

Objective: To develop a compact, cost-effective scanning microscope (BlurryScope) for HER2 scoring in breast cancer tissue samples [19].

Methodology:

- Imaging Approach: Continuous scanning producing motion-blurred images, interpreted by a specially trained deep neural network.

- Hardware: Compact system (35 × 35 × 35 cm, 2.26 kg) built for <$650 versus conventional scanners costing >$100,000.

- Sample Preparation: Standard HER2-stained breast cancer tissue sections.

- Classification: Four HER2 scoring categories (0, 1+, 2+, 3+) grouped into clinically actionable binary categories (0/1+ versus 2+/3+).

- Validation: Blinded experiments with 284 unique patient tissue cores with reproducibility testing.

Performance Validation: Achieved nearly 80% accuracy across four HER2 categories and approximately 90% accuracy for binary classification, with >86% reproducibility across repeated scans [19].

Diagnostic Parameter Relationships and Cutoff Optimization

Diagram 1: Diagnostic metric relationships as cutoff changes. PPV: Positive Predictive Value; NPV: Negative Predictive Value; FN: False Negative; FP: False Positive.

The relationship between sensitivity and specificity represents a fundamental trade-off in diagnostic test design. As the cutoff value for test positivity increases, sensitivity typically decreases while specificity increases [21]. This inverse relationship necessitates careful optimization based on clinical context.

Traditional ROC curve analysis plotting sensitivity versus (1-specificity) has been supplemented with newer approaches that provide more comprehensive diagnostic profiling. Recent methodologies include:

- Multi-Parameter ROC Curves: Integrating accuracy, precision, and predictive values alongside sensitivity and specificity [21].

- Cutoff-Index Diagrams: Enabling visualization of optimal cutoffs that balance multiple diagnostic parameters simultaneously [21].

- Two-Cutoff Approach: Implementing dual thresholds to create "rule-out" and "rule-in" zones with high confidence, acknowledging an intermediate "gray zone" where diagnostic certainty is lower [20].

For clinical decision-making, predictive values (PPV and NPV) often provide more actionable information than sensitivity and specificity alone, as they incorporate disease prevalence and provide the probability of disease given a test result [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for Diagnostic Development

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Diagnostic Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Paramagnetic Capture Beads [20] | Immobilize target molecules for detection | Simoa p-Tau 217 assay |

| Biotinylated Detector Antibodies [20] | Bind to captured analyte for signal generation | Digital immunoassays |

| Streptavidin-β-galactosidase (SβG) Conjugate [20] | Enzyme label for signal amplification | Simoa technology |

| Resorufin β-D-galactopyranoside (RGP) [20] | Fluorogenic substrate for enzymatic signal detection | Digital immunoassays |

| Purified Peptide Constructs [20] | Calibrator material for assay standardization | p-Tau 217 assay calibration |

| Heterophilic Blockers [20] | Prevent interference from heterophilic antibodies | Immunoassay reliability |

| LabelEncoder (Scikit-learn) [17] | Encode categorical variables for machine learning | AI-OCT data preprocessing |

Establishing robust benchmarks for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy remains crucial for advancing bio-optical cancer diagnostics from research tools to clinically validated solutions. The technologies examined demonstrate that while high performance is achievable across diverse platforms, the optimal approach depends heavily on the specific clinical context and application requirements.

The evolving landscape of cancer diagnostics shows a clear trend toward multi-parameter assessment, AI-enhanced interpretation, and careful cutoff optimization to maximize clinical utility. By adhering to rigorous validation standards and transparent reporting of performance metrics, researchers can accelerate the translation of innovative diagnostic technologies into tools that meaningfully impact patient care.

The Expanding Role of AI in Enhancing Bio-Optical Image Analysis and Data Interpretation

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with bio-optical imaging is fundamentally transforming oncology research and diagnostic validation. This synergy is addressing one of the most significant challenges in modern cancer care: the accurate and reproducible interpretation of complex biological images to guide therapeutic decisions. Bio-optical imaging—encompassing techniques from digital pathology to in vivo imaging—generates vast, information-rich datasets. AI algorithms, particularly deep learning and multimodal systems, are now unlocking nuanced patterns within this data that often elude human observation, thereby accelerating the path to clinical validation of novel cancer diagnostics [23] [24]. This evolution is critical for advancing precision oncology, as it enables the connection of visual morphological patterns with underlying molecular pathways and clinical outcomes.

The field is rapidly progressing from providing basic assistance to pathologists toward powering autonomous diagnostic systems and discovering novel biomarkers. By 2025, AI is no longer a speculative technology but an inseparable component of the biotech research process, converting previously impossible analytical tasks into routine procedures [25]. This review objectively compares the current performance of leading AI technologies enhancing bio-optical image analysis, detailing their experimental validation within the critical context of clinical cancer diagnostics.

Comparative Analysis of AI-Enhanced Bio-Optical Technologies

The performance of AI in bio-optical analysis can be evaluated across several key domains, including diagnostic precision, prognostic stratification, and molecular phenotype prediction. The table below summarizes quantitative data from recent studies and validated commercial tools, providing a direct comparison of their capabilities.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Technologies in Bio-Optical Image Analysis for Oncology

| Technology / Tool | Cancer Type | Primary Function | Performance Metrics | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindpeak HER2 AI Assist [26] | Breast Cancer | HER2-low/ultralow scoring on IHC slides | Diagnostic agreement: 86.4% (vs. 73.5% without AI) [26] | Misclassification of HER2-null cases decreased by 65% in a 6-center study. [26] |

| CAPAI Biomarker [26] | Stage III Colon Cancer | Risk stratification from H&E slides | 3-year recurrence: 35% (High-risk) vs. 9% (Low-risk) [26] | Identified high-risk ctDNA-negative patients for intensified monitoring. [26] |

| Stanford Spatial AI Model [26] | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | Predicts immunotherapy outcome | Hazard Ratio (PFS): 5.46 [26] | Outperformed PD-L1 scoring alone (HR=1.67) by analyzing tumor microenvironment interactions. [26] |

| Artera Multimodal AI (MMAI) [26] | Prostate Cancer | Predicts metastasis post-prostatectomy | 10-year metastasis risk: 18% (High-risk) vs. 3% (Low-risk) [26] | Combined H&E image features with clinical variables (age, PSA, Gleason grade). [26] |

| MIA:BLC-FGFR Algorithm [26] | Bladder Cancer | Predicts FGFR status from H&E slides | AUC: 80-86% [26] | Offers a rapid, tissue-efficient alternative to molecular testing for trial enrollment. [26] |

| Digital PATH Project Tools [27] | Breast Cancer | Quantify HER2 expression | High agreement with experts for strong expression; greater variability in low/HER2-low cases. [27] | Analysis of 1,100 samples highlighted the need for standardized validation in low-expression ranges. [27] |

| Prov-GigaPath, Owkin Models [28] | Various Cancers | Foundation models for cancer detection & biomarker discovery | Outperforms human experts in specific tasks (e.g., mammogram interpretation). [28] | DeepHRD tool detects HRD characteristics with 3x more accuracy than some genomic tests. [28] |

Key Performance Insights from Comparative Data

The comparative data reveals several critical trends. First, AI tools consistently enhance diagnostic precision and agreement among pathologists, particularly in challenging, subjective tasks like scoring HER2-low breast cancer [26]. Second, AI models extracting spatial and morphological features from standard H&E slides demonstrate powerful prognostic value, stratifying patient risk beyond traditional biomarkers like ctDNA or PD-L1 [26]. Finally, the ability of AI to predict molecular alterations (e.g., FGFR status) from routine histology presents a paradigm shift, potentially making advanced genomic profiling more accessible and cost-effective [26].

Experimental Protocols for AI Tool Validation

The rigorous validation of AI tools is paramount for their acceptance in clinical research. The following section details the methodologies underpinning key experiments cited in this review, providing a framework for evaluating new technologies.

Protocol 1: Validation of AI for Biomarker Scoring (HER2)

This protocol is based on the international multi-center study that validated the Mindpeak AI tool for HER2 scoring [26].

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy and concordance of pathologists, with and without AI assistance, in digitally scoring HER2 IHC levels, including the challenging HER2-low and ultralow categories.

- Sample Preparation:

- Tissue Source: Archived breast cancer tumor samples.

- Staining: Serial sections are stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and anti-HER2 IHC according to standard clinical laboratory protocols.

- Digitization: All stained slides are scanned using a high-throughput whole-slide scanner to create digital whole-slide images (WSIs).

- AI Analysis:

- The AI algorithm is trained on a large dataset of HER2-labeled WSIs.

- For the validation study, the AI processes the IHC WSIs to generate an initial HER2 score (0, 1+, 2+, 3+).

- Pathologist Assessment:

- A cohort of pathologists from multiple international academic centers independently scores the same set of WSIs.

- The same pathologists then re-score the WSIs with the assistance of the AI's output.

- Outcome Measures:

- Diagnostic Agreement: The inter-observer agreement rate among pathologists with and without AI assistance.

- Misclassification Rate: The rate of incorrect classification, particularly for HER2-null cases that should not receive targeted therapy.

Protocol 2: Development of a Spatial Biomarker for Immunotherapy

This protocol outlines the methodology used by Stanford researchers to develop an AI model for predicting outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in NSCLC [26].

- Objective: To identify and quantify features within the tumor microenvironment (TME) on H&E slides that predict progression-free survival (PFS) in patients treated with immunotherapy.

- Sample Preparation:

- Tissue Source: H&E-stained biopsy slides from NSCLC patients before treatment with immunotherapy.

- Digitization: Slides are scanned to create WSIs.

- AI Training & Feature Extraction:

- The AI model, based on a deep learning architecture, is trained to identify and segment different cell types (tumor cells, fibroblasts, T-cells, neutrophils) and tissue structures.

- The model analyzes the spatial relationships and interactions between these components (e.g., proximity of T-cells to tumor cells).

- A model comprising five key spatial features is constructed.

- Data Integration & Statistical Analysis:

- The AI-generated spatial biomarker score is correlated with clinical outcome data (PFS).

- The predictive power of the AI model is compared against standard-of-care biomarkers like PD-L1 tumor proportion score using hazard ratios from survival analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Enhanced Bio-Optical Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Workflow | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| H&E Staining Kits | Provides standard morphological context on tissue sections. | Basis for all diagnostic and AI-based risk stratification models (e.g., CAPAI, Stanford spatial model). [26] |

| IHC Assays & Antibodies | Enables visualization of specific protein biomarkers (e.g., HER2, PD-L1). | Gold standard for validating AI-predicted protein expression levels. [26] |

| Bioluminescent/Fluorescent Reporters | Allows non-invasive, real-time tracking of biological processes in vivo. | Used in preclinical optical imaging for studying drug efficacy and disease progression in animal models. [29] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kits | Provides genomic ground truth data (e.g., mutations, HRD status). | Used to validate AI models that predict genomic alterations from histology images (e.g., DeepHRD, MIA:BLC-FGFR). [28] [26] |

| Digital Whole-Slide Scanners | Converts physical glass slides into high-resolution digital images for AI analysis. | Foundational hardware for all digital pathology workflows; critical for image quality and subsequent AI accuracy. [27] |

Visualizing AI Workflows in Cancer Diagnostics

The integration of AI into bio-optical analysis follows structured workflows. The diagram below illustrates a generalized pipeline for developing and validating an AI model for cancer diagnosis and prognosis.

Foundation models are becoming a core architectural component in modern AI systems for digital pathology. The diagram below details how these pre-trained models are fine-tuned for specific diagnostic tasks.

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite the promising advances, the clinical validation and deployment of AI-powered bio-optical diagnostics face several hurdles. A significant challenge is the "black box" nature of some complex AI models, where the reasoning behind a decision is not transparent, raising concerns for clinical adoption [24]. Ensuring data privacy, navigating regulatory frameworks for software as a medical device, and guaranteeing generalizability across diverse patient populations and imaging equipment are active areas of focus [27] [23] [24]. Furthermore, the initial high cost of advanced imaging systems and a shortage of skilled personnel for operation and data analysis can limit uptake, particularly in smaller institutions and emerging markets [29].

Future development will likely focus on multimodal AI that seamlessly integrates histology, genomics, and clinical data for a holistic patient profile [24] [26]. The use of federated learning—training algorithms across multiple institutions without sharing patient data—is a promising approach to overcome data privacy and scarcity issues [23]. Finally, the push for standardized regulatory science, as exemplified by the Friends of Cancer Research Digital PATH Project, is critical for establishing benchmarks and ensuring that these powerful tools are validated with the same rigor as traditional diagnostics [27]. As these technologies mature, they hold the undeniable potential to make cancer diagnostics more precise, accessible, and profoundly impactful on patient outcomes.

Building a Validated Assay: Methodologies and Integrated Applications in Clinical Workflows

The clinical validation of bio-optical cancer diagnostics represents a complex multidisciplinary challenge, requiring a structured approach to ensure analytical robustness and clinical relevance. Strategic validation frameworks provide the necessary scaffolding to navigate this complexity, integrating analytical measurements, orthogonal verification methods, and rigorous clinical utility assessment. Within oncology research and drug development, these frameworks enable researchers and scientists to transform innovative diagnostic concepts into clinically validated tools that can reliably inform patient management decisions. The convergence of advanced optical technologies with artificial intelligence has further accelerated the need for sophisticated validation strategies that can keep pace with diagnostic innovation while meeting regulatory standards.

The fundamental purpose of validation in this context is to assure the safety and efficacy of medicinal products and diagnostic tools in clinical settings [30]. This process hinges on the comprehensive evaluation of Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)—properties of a biotherapeutic or diagnostic sample that indicate its general stability and quality, which may be connected to product efficacy [30]. For bio-optical cancer diagnostics, these attributes typically include analytical sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and clinical performance metrics that must be thoroughly characterized throughout development and manufacturing. The strategic frameworks guiding this characterization employ a hierarchical approach that moves from basic analytical validation through orthogonal verification and ultimately to assessment of clinical utility, creating a robust chain of evidence that supports diagnostic adoption.

Comparative Framework for Strategic Validation

Analytical Validation Frameworks

Analytical validation establishes that a diagnostic test reliably measures what it claims to measure, forming the foundational layer of the validation pyramid. For bio-optical cancer diagnostics, this involves demonstrating performance characteristics such as accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility under controlled conditions. The Balanced Scorecard (BSC) framework offers a structured approach to analytical validation by balancing multiple perspectives—including internal process quality, learning and growth in methodological refinements, and stakeholder requirements—through cause-and-effect logic that connects improvement goals with performance indicators and action plans [31]. This framework ensures that analytical validation activities remain aligned with broader strategic objectives rather than occurring in isolation.

The Objectives and Key Results (OKR) framework provides a more agile complement to BSC for managing analytical validation, particularly useful for focusing teams on specific, inspirational goals with quarterly review cycles that maintain momentum in development projects [31]. For the highly structured environment of diagnostic validation, the Hoshin Kanri framework emphasizes continuous improvement through its Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle and promotes strategic alignment through "Catchball" discussions that ensure all team members understand and contribute to validation objectives [31]. When selecting an analytical validation framework, researchers must consider factors such as the diagnostic's development stage, organizational structure, and regulatory requirements, as each framework offers distinct advantages for different contexts.

Table 1: Comparison of Strategic Frameworks for Analytical Validation

| Framework | Primary Focus | Key Components | Application in Bio-Optical Diagnostics | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Scorecard (BSC) | Strategy execution with balanced perspective | Strategy maps, four perspectives (internal, learning & growth, customer, stakeholders), cause-effect logic, leading/lagging indicators | Connects analytical performance goals with clinical outcomes through measurable indicators | Comprehensive strategic alignment, strong cause-effect documentation |

| OKR | Agile goal setting for specific challenges | Objectives (inspirational goals), Key Results (measurable outcomes), quarterly cycles | Rapid iteration on specific analytical parameters during development | Lightweight, adaptable, promotes focus and alignment on critical goals |

| Hoshin Kanri | Strategy deployment through continuous improvement | Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle, Catchball process, X-matrix for strategic priorities | Systematic approach to improving analytical methods and processes | Emphasizes learning and adaptation, strong alignment through discussion |

| OGSM Model | Strategic planning with one-page overview | Objectives, Goals, Strategies, Measures structured document | Clear documentation of analytical validation strategy and progress | Simplicity and clarity, easy communication across teams |

| Results-Based Management | Cause-effect logic for outcome achievement | Inputs, Activities, Outputs, Outcomes, Impact hierarchy with quantification | Tracking analytical validation activities through to clinical impact | Strong focus on measurable outcomes and impact demonstration |

Orthogonal Verification Frameworks

Orthogonal verification represents a critical strategic layer in diagnostic validation, employing methodologies based on different physicochemical or biological principles to assess the same attributes, thereby providing independent data to support quality assessments [30]. The fundamental principle of orthogonality in analytical science acknowledges that each measurement technique introduces specific biases or systematic errors due to its operating principles, making confirmation through independent methods essential for robust validation [32] [30]. For bio-optical cancer diagnostics, this typically involves employing multiple measurement techniques that probe the same critical quality attributes through different physical mechanisms, such as combining label-free optical methods with fluorescence-based detection or correlating optical measurements with non-optical techniques like mass spectrometry.

The strategic implementation of orthogonal methods follows a structured framework that begins with identifying Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) most relevant to clinical performance, then selecting appropriate orthogonal technique pairs that measure the same CQAs through different principles [30]. For example, in assessing subvisible particles in diagnostic reagents—a key quality attribute—researchers might employ both Flow Imaging Microscopy (FIM) and Light Obscuration (LO), as both measure particle count and size but use digital imaging versus light blocking principles respectively [30]. This orthogonal approach is particularly valuable when the primary technique is qualitative or when the CQA is dynamic and cannot be completely mapped by a single method [32]. The regulatory emphasis on orthogonal approaches reflects their importance in providing unambiguous demonstration of biosimilarity in pharmaceutical development, a principle that extends directly to bio-optical diagnostics validation [32].

Table 2: Orthogonal Technique Pairs for Bio-Optical Diagnostic Validation

| Critical Quality Attribute | Primary Optical Method | Orthogonal Verification Method | Measurement Principle Difference | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Concentration & Size | Flow Imaging Microscopy (FIM) | Light Obscuration (LO) | Digital imaging vs. light blocking | Subvisible particle analysis in diagnostic reagents [30] |

| Protein Aggregation | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) | Brownian motion vs. sedimentation velocity | Stability of protein-based recognition elements [32] |

| Nanoparticle Morphology | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Electron interaction vs. physical probing | Characterization of optical contrast agents [33] |

| Molecular Structure | Circular Dichroism (CD) | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Optical activity vs. magnetic properties | Confirmation of biorecognition element structure |

| Surface Properties | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Refractive index changes vs. electron emission | Functionalization of optical biosensors |

Clinical Utility Assessment Frameworks

Clinical utility assessment forms the capstone of the validation pyramid, evaluating whether a diagnostic test provides information that leads to improved patient outcomes, better survival rates, or more efficient healthcare delivery. For bio-optical cancer diagnostics, this involves generating evidence that the diagnostic meaningfully impacts clinical decision-making, treatment selection, or patient management in real-world settings. The McKinsey Three Horizons framework offers a strategic approach to planning and validating clinical utility by categorizing innovation according to three time frames: current core applications (now), emerging applications in the comfort zone (near-term future), and potentially disruptive future applications (future) [31]. This framework helps diagnostic developers allocate appropriate validation resources across their development pipeline while maintaining focus on both immediate and long-term clinical utility.

Artificial intelligence integration in bio-optical cancer diagnostics has expanded the scope of clinical utility assessment, requiring frameworks that can validate both the optical technology and the algorithmic components. Recent advances in deep learning have demonstrated remarkable potential in addressing previously insurmountable challenges in cancer detection and diagnosis [34]. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) applied to optical imaging data have shown performance comparable or superior to human experts in tasks such as tumor detection, segmentation, and grading [34]. The validation of these AI-enhanced diagnostics requires specialized frameworks that assess not only traditional clinical performance metrics but also algorithmic robustness, generalizability across diverse populations, and integration into clinical workflows.

Table 3: Clinical Performance of AI-Enhanced Bio-Optical Cancer Diagnostics

| Cancer Type | Optical Modality | AI System | Dataset Size | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | Colonoscopy | CRCNet | 464,105 images from 12,179 patients (training) | 91.3% (AI) vs. 83.8% (human) | 85.3% (AI) | 0.882 (95% CI: 0.828-0.931) | Retrospective multicohort diagnostic study with external validation [34] |

| Breast Cancer | 2D Mammography | Ensemble of three DL models | 25,856 women (UK) 3,097 women (US) | +2.7% vs. first reader (UK) +9.4% vs. radiologists (US) | +1.2% vs. first reader (UK) +5.7% vs. radiologists (US) | 0.889 (UK) 0.8107 (US) | Diagnostic case-control study with comparison to radiologists [34] |

| Colorectal Cancer | Colonoscopy/Histopathology | Real-time image recognition system | 118 lesions from 41 patients | 95.9% (neoplastic lesion detection) | 93.3% (nonneoplastic identification) | Not Reported | Prospective diagnostic accuracy study with blinded gold standard [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Protocol for Analytical Validation of Bio-Optical Assays

A robust analytical validation protocol for bio-optical cancer diagnostics must systematically address multiple performance characteristics using standardized methodologies. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach:

Accuracy Assessment: Compare diagnostic results from the bio-optical assay against a gold standard reference method using clinically characterized specimens spanning the assay's intended use population. Calculate percent agreement, sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy with 95% confidence intervals. For quantitative assays, use linear regression and Bland-Altman analysis to assess systematic and proportional bias.

Precision Evaluation: Conduct within-run, between-run, and between-operator precision studies following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP05-A3 guidelines. Test at least two levels of controls (normal and pathological ranges) with 20 replicates per level for within-run precision, and duplicate measurements over 10 days for between-run precision. Calculate coefficients of variation (CV) with acceptance criteria typically <15% for biomarker assays.

Linearity and Reportable Range: Prepare a series of samples with analyte concentrations spanning the claimed measuring range, typically through serial dilution of high-concentration samples. Test each dilution in triplicate and plot observed versus expected values. Establish the reportable range as the interval over which linearity, precision, and accuracy claims are met.

Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ): Determine LOD using at least 20 replicates of blank (analyte-free) samples and low-concentration samples near the expected detection limit. Calculate LOD as mean blank value + 3 standard deviations. Establish LOQ as the lowest concentration that can be measured with ≤20% CV while maintaining stated accuracy requirements.

Interference and Cross-Reactivity Testing: Evaluate potential interferents including hemoglobin, lipids, bilirubin, common medications, and structurally similar compounds that might cross-react. Spike interferents at clinically relevant concentrations and assess recovery against non-spiked controls.

Protocol for Orthogonal Verification Studies

Orthogonal verification requires careful experimental design to ensure methods truly provide independent assessment of the same attributes:

Orthogonal Technique Selection: Identify technique pairs that measure the same Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) but employ fundamentally different measurement principles [30]. For example, combine flow imaging microscopy (measurement principle: digital imaging of particles) with light obscuration (measurement principle: light blocking by particles) for subvisible particle analysis [30].

Sample Preparation for Orthogonal Analysis: Use identical sample aliquots for both primary and orthogonal methods to eliminate preparation variability. Ensure sample stability throughout the testing window and document handling conditions.

Comparative Testing Protocol: Analyze a minimum of 3-5 lots of samples representing expected variation in manufacturing or clinical use. For each lot, perform triplicate measurements using both primary and orthogonal methods in randomized order to avoid sequence effects.

Data Correlation Analysis: Assess agreement between methods using appropriate statistical approaches based on data type. For continuous data, use Pearson or Spearman correlation, Deming regression, and concordance correlation coefficients. For categorical data, calculate percent agreement and Cohen's kappa.

Bias Assessment and Resolution: Systematically identify and document discrepancies between orthogonal methods. Investigate technical reasons for discrepancies related to methodological biases, such as differential sensitivity to particle translucency in particle counting methods [30]. Establish acceptance criteria for orthogonal agreement prior to testing.

Protocol for Clinical Utility Assessment

Clinical utility assessment requires multidimensional evaluation of real-world performance and impact:

Diagnostic Performance Study: Conduct a prospective, blinded validation study comparing the bio-optical diagnostic against the clinical reference standard in the intended use population. Pre-specify primary endpoints (sensitivity, specificity, AUC), secondary endpoints (PPV, NPV, likelihood ratios), and statistical power calculations. Include diverse patient subgroups to assess generalizability.

Clinical Impact Assessment: Design studies evaluating how diagnostic results influence clinical decision-making, such as treatment selection, additional testing, or referral patterns. Use methods including surveys, interviews, and observation of clinical workflows before and after diagnostic implementation.

Health Outcomes Analysis: For diagnostics claiming improved patient outcomes, collect data on relevant endpoints such as time to diagnosis, treatment response rates, progression-free survival, or overall survival. Adjust for potential confounders using multivariate statistical methods.

Economic Evaluation: Perform cost-effectiveness analysis comparing the bio-optical diagnostic against current standard of care. Include direct medical costs, indirect costs, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) where appropriate. Conduct sensitivity analyses to assess robustness of conclusions to parameter uncertainty.

Visualization of Strategic Validation Workflows

Integrated Validation Strategy Diagram

Validation Strategy Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated sequential approach to bio-optical diagnostic validation, moving from analytical validation through orthogonal verification to clinical utility assessment.

Orthogonal Method Selection Algorithm

Orthogonal Method Selection: This decision algorithm outlines the process for selecting appropriate orthogonal methods based on measurement principles, dynamic ranges, and validation status.

Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

The successful implementation of strategic validation frameworks requires specific research reagents and materials carefully selected for their intended functions in analytical, orthogonal, and clinical utility assessment.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Bio-Optical Diagnostic Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Specific Application Examples | Quality Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characterized Reference Materials | Serve as gold standard for accuracy assessment and calibration | Certified tumor markers, cell line derivatives with known mutation status | Traceable to international standards, certificate of analysis with documented uncertainty |

| Multiplex Quality Controls | Monitor assay precision across multiple analytes and concentrations | Commercial serum/plasma controls with predetermined values for oncology biomarkers | Defined acceptability ranges, stability documentation, commutable with patient samples |

| Interference Testing Panels | Evaluate assay susceptibility to common interferents | Hemolyzed, icteric, and lipemic samples; common medication panels | Clinically relevant interference concentrations, standardized preparation protocols |

| Stability Testing Materials | Assess reagent and sample stability under various conditions | Temperature-controlled storage systems, light exposure chambers | Environmental monitoring capability, standardized challenge conditions |

| Orthogonal Method Kits | Provide independent measurement of same analytes | ELISA kits for protein biomarkers when primary method is optical immunoassay | Different methodological principle, validated performance characteristics |

| Clinical Sample Panels | Validate diagnostic performance in intended use population | Well-characterized specimens with reference method results and clinical outcomes | IRB-approved collection protocols, comprehensive clinical annotation, appropriate storage conditions |

Strategic validation frameworks provide an essential structured approach for establishing the analytical robustness and clinical utility of bio-optical cancer diagnostics. By integrating analytical validation, orthogonal verification, and clinical utility assessment within a cohesive strategy, researchers and drug development professionals can systematically address the complex challenges of diagnostic validation while meeting regulatory standards. The comparative framework analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that no single approach fits all scenarios—rather, the selection of specific frameworks must align with the diagnostic's development stage, technological complexity, and intended clinical application.

The accelerating integration of artificial intelligence with bio-optical technologies necessitates continued evolution of these validation frameworks, particularly in addressing novel challenges related to algorithmic validation and clinical generalizability. Furthermore, the established principle of orthogonality from biotherapeutic development offers valuable guidance for bio-optical diagnostics, emphasizing the importance of independent methodological verification to overcome technique-specific biases and limitations. As the field advances, these strategic frameworks will play an increasingly critical role in translating technological innovations into clinically validated tools that reliably improve cancer patient outcomes.

Integrated multi-omic approaches represent a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving beyond single-layer molecular analysis to a comprehensive systems biology perspective. By combining DNA sequencing (genomics), RNA sequencing (transcriptomics), and various forms of optical imaging, researchers can now capture complementary information across multiple biological layers—from genetic blueprint to functional activity and spatial organization [35] [36]. This integration is particularly transformative in oncology, where complex molecular interactions and tissue-level manifestations must be correlated to understand disease mechanisms, identify biomarkers, and develop targeted therapies [37] [36].

The clinical validation of bio-optical cancer diagnostics depends on this multi-modal approach, as it enables researchers to trace the flow of biological information from DNA variations through RNA expression to protein function and metabolic activity, while simultaneously capturing structural and compositional changes through imaging [38] [39]. This guide objectively compares the performance, requirements, and applications of different integration methodologies, providing researchers with experimental protocols and analytical frameworks for implementing these powerful approaches in cancer research.

Multi-Omic Integration Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Conceptual Frameworks for Data Integration

Multi-omics data integration strategies can be categorized into distinct conceptual frameworks, each with specific strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases. The table below compares the primary integration approaches used in contemporary research.

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Omics Data Integration Approaches

| Integration Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal Integration | Combining multiple datasets of the same omics type from different batches or sources [38] | Standardizes data across platforms; reduces batch effects | Limited to single omics layer; cannot capture cross-omics interactions | Merging genomic datasets from multiple sequencing centers; cross-study transcriptomic comparisons |

| Vertical Integration | Combining diverse omics datasets (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) from the same samples [38] | Captures complementary biological information; enables systems-level analysis | Complex statistical integration; requires careful normalization | Identifying biomarkers across molecular layers; mapping information flow from DNA to RNA to protein |

| Concatenation-Based | Early integration by merging features from different omics into a single matrix [40] [37] | Simple implementation; preserves all feature relationships | Creates high-dimensional data; requires strong normalization; sensitive to outliers | Small datasets with similar feature scales; when computational resources are limited |

| Transformation-Based | Converting each omics dataset into a simplified representation before integration [40] [37] | Reduces dimensionality; handles different data types effectively | May lose biologically relevant variance; complex interpretation | Large-scale multi-omics studies; integration of disparate data types (e.g., sequences and images) |

| Model-Based | Using statistical models to integrate omics layers while preserving their structures [40] | Accounts for data structure; robust to noise | Computationally intensive; complex implementation | Studies with clear biological priors; causal inference analysis |

| Graph-Based | Representing multi-omics data as networks with nodes and edges [37] | Captures complex relationships; incorporates biological prior knowledge | Requires specialized expertise; computationally intensive | Mapping molecular interactions; identifying network perturbations in disease |

Performance Benchmarking of Integration Methods

Recent comprehensive evaluations have assessed various integration methods for key performance metrics in cancer subtyping and biomarker discovery. The benchmarking results provide critical guidance for method selection based on research objectives.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Multi-Omics Integration Methods for Cancer Subtyping

| Method | Category | Clustering Accuracy | Clinical Significance | Robustness | Computational Efficiency | Recommended Omics Combinations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) | Network-based | High | High | Medium | Medium | mRNA + miRNA + DNA methylation |

| iClusterBayes | Statistics-based | High | High | High | Low | mRNA + DNA methylation + copy number variation |

| MOFA+ | Transformation-based | Medium-High | Medium-High | High | Medium | Any combination with >2 omics types |

| LRAcluster | Statistics-based | Medium | Medium | Medium | High | mRNA + miRNA |

| Pattern Fusion Analysis (PFA) | Network-based | Medium-High | Medium | Medium | Medium | mRNA + protein expression |

| Subtype-GAN | Deep Learning | High | Medium | Low | Low | All major omics types combined |

Key Insights from Performance Evaluation: Contrary to intuitive expectations, incorporating more omics data types does not always improve performance. Some integration methods perform better with specific combinations—for example, mRNA expression with DNA methylation data often yields more clinically relevant cancer subtypes than simply adding more data types [40]. The optimal combination depends on both the biological context and the specific integration method employed.

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omic Profiling

The Quartet Project Protocol for Multi-Omic Reference Materials

The Quartet Project provides a robust framework for quality control and data integration in multi-omics studies, using reference materials from immortalized cell lines of a family quartet (parents and monozygotic twin daughters) [38].

Protocol Overview:

Reference Material Preparation: Simultaneous establishment of DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolite reference materials from the same B-lymphoblastoid cell lines, with large batch production (>1,000 vials each) to ensure consistency [38].

Cross-Platform Profiling: Analysis of reference materials across multiple technology platforms:

- 7 DNA sequencing platforms

- 1 DNA methylation platform

- 2 RNA-seq platforms

- 2 miRNA-seq platforms

- 9 LC-MS/MS-based proteomics platforms

- 5 LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics platforms [38]

Ratio-Based Profiling Implementation:

- Scale absolute feature values of study samples relative to a concurrently measured common reference sample

- Calculate ratios on a feature-by-feature basis (e.g., D5/D6, F7/D6, M8/D6)

- Apply these ratios to eliminate systematic biases across batches and platforms [38]

Quality Control Metrics: