Biophotonics: The Complete Guide to Light-Based Technologies in Biomedicine and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of biophotonics, the interdisciplinary field harnessing light to analyze and manipulate biological systems.

Biophotonics: The Complete Guide to Light-Based Technologies in Biomedicine and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of biophotonics, the interdisciplinary field harnessing light to analyze and manipulate biological systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of light-tissue interaction, details cutting-edge methodologies from imaging to therapy, and analyzes the integration of AI and nanotechnology for optimization. The scope extends to current market trends, validation frameworks, and the transformative role of biophotonics in advancing precision medicine, non-invasive diagnostics, and targeted therapeutic applications.

Biophotonics Fundamentals: Principles of Light-Biology Interaction and Core Technologies

Biophotonics, derived from the Greek words "bios" (life) and "phos" (light), is an interdisciplinary field that represents the innovative convergence of biology, medicine, and photonics—the science and technology of generating, controlling, and detecting light [1]. This dynamic discipline employs light to analyze and manipulate biological materials, offering groundbreaking possibilities for both fundamental research and practical applications across various industries, including pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and medicine [1]. By leveraging optical techniques, biophotonics allows scientists to capture cellular conditions and monitor dynamic processes, providing a comprehensive view of life processes at molecular, cellular, tissue, and organ levels [1].

The potential applications of biophotonics are numerous and diverse, encompassing fundamental investigations of cell processes as well as health-related applications such as diagnostics, therapy monitoring, and well-being assessment [1]. Furthermore, biophotonic technologies contribute significantly to environmental monitoring, food safety, and agricultural advancements [1]. The field stands at the forefront of scientific innovation, offering profound insights into biological and biomedical processes and paving the way for new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches that are transforming research, diagnostics, and therapy across multiple domains [1].

Core Principles and Technologies

Fundamental Light-Matter Interactions

Biophotonic techniques study the structural, functional, mechanical, biological, and chemical properties of biological materials through various light interactions, including absorption, emission, reflection, and scattering [1]. These interaction phenomena elucidate a vast array of morphological and molecular intricacies across macroscopic, microscopic, and nanoscopic resolutions [1]. The field can be broadly divided into three main technological areas:

- Bioimaging: Photonics technologies enable the characterization of biological specimens across multiple spatial scales, from the nanoscopic level—facilitating the investigation of intracellular interactions—to the microscopic and macroscopic domains, including tissues and muscle structures [1].

- Biosensing: Photonic-based approaches allow for the detection of biomolecules, such as disease-specific biomarkers, with sensitivities reaching molecular concentrations and, in principle, single-molecule resolution [1].

- Treatment and Control: Lasers and other light sources facilitate highly precise and minimally invasive surgical interventions, while bioimaging and biosensing modalities enable real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy and post-operative recovery [1].

Key Advantages of Biophotonic Technologies

The use of light in biophotonics offers several distinct advantages that make it particularly valuable for biological and medical applications:

- Non-contact measurement: Light facilitates the observation of living cells noninvasively, preserving the integrity of analyzed cells and avoiding toxic effects [1].

- Speed and instant information: Optical measurements provide rapid, real-time data, significantly reducing the time required for data interpretation and diagnosis [1].

- Sensitivity: Optical technologies allow for ultrasensitive detection, down to single molecules, which is essential for understanding fundamental biological processes [1].

- Time resolution: Optical methods enable the observation of dynamic biological processes over a range of temporal scales, from hours to ultrafast reactions [1].

Key Technological Modalities in Biophotonics

Advanced Bioimaging Techniques

Bioimaging represents one of the most developed applications of biophotonics, with numerous sophisticated modalities available for research and clinical use:

Label-free diagnostic methods include several powerful technologies. Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) and fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) of endogenous fluorophores provide molecular contrast by visualizing native electronic chromophores such as hemoglobin, NADP(H), flavin, elastin, or cytochrome [1]. Second harmonic generation (SHG) and third harmonic generation (THG) visualize specific structural proteins (e.g., collagen) and phase boundaries, respectively [1]. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides detailed imaging of tissue architecture down to the cellular level by detecting changes in refractive index [1]. Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) combines optical absorption with ultrasonic detection for deep-tissue imaging [1]. Vibrational microspectroscopy, including infrared (IR) absorption and Raman scattering, offers molecule-specific contrast for visualizing spatial distribution of molecular markers such as proteins, lipids, or DNA [1].

Recent advances in compact high-intensity ultrashort laser sources have enabled the exploitation of nonlinear optical phenomena for biomedical imaging, resulting in significant improvements in penetration depth, optical resolution, and acquisition speed [1]. Multi-photon absorption, in particular, is valuable for microscopy applications as the simultaneous absorption of two or three photons leads to precise localization of fluorescence or harmonic generation signals [1]. Coherent Raman scattering (CRS) phenomena such as CARS (coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering) and SRS (stimulated Raman scattering) enhance the intrinsically weak Raman signal and avoid being swamped by autofluorescence background [1].

Biosensing Platforms

Biophotonic biosensing leverages optical phenomena such as fluorescence, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and Raman spectroscopy to enable highly sensitive, often label-free detection of biological and chemical analytes [2]. The growing emphasis on point-of-care testing (POCT) and wearable biosensing technologies for early disease detection, remote patient monitoring, and real-time health analytics has significantly driven advancement in this area [2].

Incorporating nanophotonic elements such as plasmonic nanoparticles, quantum dots, and photonic crystals has facilitated ideal biosensor performance, enabling ultrasensitive tracking of DNA, proteins, and biomarkers in small volumes [2]. These advancements support enhanced disease screening, personalized medicine, and early-stage cancer detection [2]. The rise of wearable health monitoring devices integrated with AI-driven biosensors in smartwatches, patches, and implantable sensors further exemplifies the growing application of biophotonic biosensing for continuous monitoring of glucose levels, oxygen saturation, and cardiovascular biomarkers [2].

Therapeutic Applications

Light-based therapeutic modalities represent another major application area for biophotonics. Lasers and other advanced light sources are used for facilitating highly precise and minimally invasive surgical interventions [1]. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) combines light-sensitive compounds with specific light wavelengths to selectively target and destroy abnormal cells [3]. Laser therapies are well-established in various medical specialties, including ophthalmology, dermatology, and oncology [3].

The integration of bioimaging and biosensing modalities with therapeutic applications enables real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy and post-operative recovery, creating a closed-loop system for precision medicine [1]. This convergence of diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities within a single platform represents a significant advancement in medical technology, allowing for personalized treatment approaches and improved patient outcomes.

Quantitative Market Outlook and Adoption Trends

The growing importance of biophotonics is reflected in market projections and adoption trends across various sectors and regions. The table below summarizes key quantitative data on the biophotonics market size, growth rates, and regional adoption:

Table 1: Biophotonics Market Size and Growth Projections

| Metric | 2024/2025 Value | 2034/2035 Projection | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Market Size | USD 76.1 billion (2024) [3] | USD 220.1 billion (2034) [3] | 11.3% [3] | Nanotechnology, aging population, lifestyle diseases [3] |

| Alternative Market Estimate | USD 67.2 billion (2025) [2] | USD 189.3 billion (2035) [2] | 10.9% [2] | Non-invasive diagnostics, surgical visualization [2] |

| In-Vivo Segment Share | 57% (2024) [3] | Dominance through forecast period [3] | - | Optical imaging, laser diagnostics [3] |

| In-Vitro Segment Size | - | USD 89.6 billion (2034) [3] | - | Automation, AI-based analysis [3] |

| See-Through Imaging Segment | - | - | 13.7% [3] | Non-invasive, high-resolution visualization [3] |

Table 2: Regional Market Analysis and Key Characteristics

| Region/Country | Market Size | Growth Rate (CAGR) | Key Characteristics & Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | - | - | Massive R&D investment, advanced healthcare infrastructure [3] |

| Germany | USD 3.6 billion (2024) [3] | - | Strong R&D, multiphoton microscopy, OCT adoption [3] |

| China | - | 14.1% [3] | Aggressive R&D investments, government strategic initiatives [3] |

| India | - | - | USD 8.7 billion (2034 projection) [3] |

| Japan | USD 3.3 billion (2024) [3] | - | Aging population, chronic disease prevalence [3] |

Application segments show varying growth patterns and market dynamics. The spectro molecular segment held the largest market share at USD 15.1 billion in 2024, driven by technological progress that has improved the sensitivity and accuracy of spectroscopic devices [3]. The tests and components segment dominated end-use applications with a 35.4% share in 2024, reflecting increasing demand for advanced diagnostic tools and highly reliable imaging components [3]. The medical therapeutics segment is growing at the highest rate and is expected to reach a market size of USD 83.7 billion in 2034, fueled by expansion in laser therapies, photodynamic therapy, and other light-based treatments [3].

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Core Experimental Workflow in Biophotonics Research

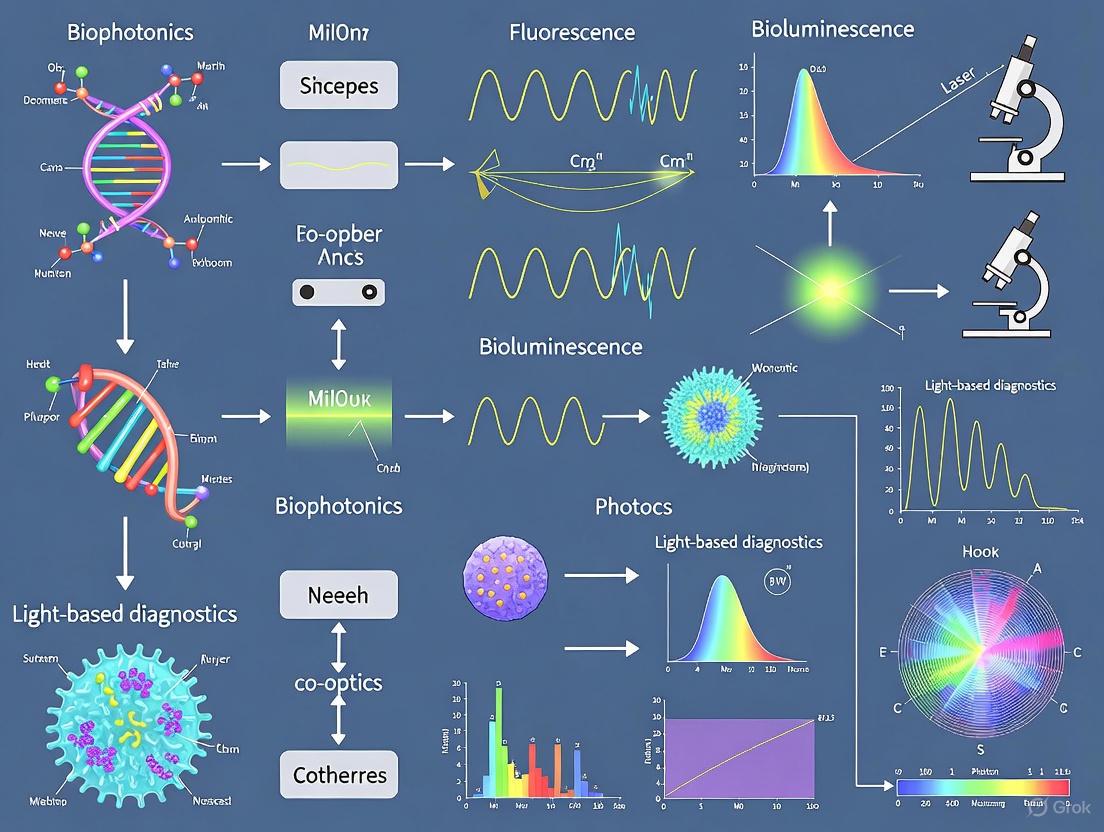

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for biophotonics research, highlighting the interconnected nature of various technologies and applications:

Detailed Methodologies for Key Techniques

Multiphoton Microscopy Protocol

Principle: Simultaneous absorption of two or three photons of longer wavelength (typically NIR) leads to precise localization of fluorescence or harmonic generation signals, enabling deep tissue imaging with high spatial resolution [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Fix or maintain live biological specimens (cells, tissues, or small organisms) in appropriate mounting media compatible with optical imaging [1].

- Labeling (if required): Introduce fluorescent markers (endogenous or exogenous) that exhibit multiphoton absorption characteristics [4].

- System Setup: Configure Ti:sapphire femtosecond laser source tuned to appropriate wavelength (typically 700-1100 nm) [1]. Align laser scanning microscope system with high-sensitivity detectors (photomultiplier tubes or GaAsP detectors) [1] [2].

- Image Acquisition: Focus laser beam on sample using high-numerical-aperture objective lens. Scan beam across sample region of interest while collecting emitted fluorescence signals through non-descanned detectors [1].

- Data Collection: Acquire 3D image stacks by sequential imaging at different depths. For dynamic processes, collect time-series data at appropriate temporal resolution [1].

- Processing: Reconstruct 3D volumes from z-stacks. Apply necessary corrections for background subtraction, flat-field correction, and photon counting analysis [1].

Raman Spectroscopy and CRS Protocol

Principle: Inelastic scattering of light provides vibrational fingerprint of molecules, with CRS (CARS/SRS) enhancing weak Raman signals through coherent excitation [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare thin sections or concentrated solutions of biological material. Minimal preparation required as Raman is inherently label-free [1].

- System Setup:

- Data Acquisition:

- Spectral Processing: Remove cosmic rays, correct for background fluorescence, normalize spectra, and perform multivariate analysis for chemical mapping [1].

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) Protocol

Principle: Interferometric detection of backscattered light to reconstruct depth-resolved tissue microstructure with micron-scale resolution [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Minimal preparation required. Can image tissues in vivo or ex vivo without sectioning [1].

- System Setup: Configure broadband light source (superluminescent diode or laser), Michelson interferometer with reference arm, and spectrometer-based or swept-source detection system [1].

- Data Acquisition: Scan reference arm length while detecting interference pattern. Reconstruct depth profile (A-scan) at each lateral position [1].

- Image Reconstruction: Perform Fourier transform on spectral interference patterns to reconstruct depth-resolved reflectivity profiles. Combine sequential A-scans to form 2D cross-sections (B-scans) or 3D volumes [1].

- Extension to SOCT: Acquire wavelength-dependent backscattering to determine concentration of tissue chromophores through spectroscopic OCT [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful biophotonics research requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for specific optical techniques. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for experimental work in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biophotonics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Markers & Dyes | Labeling cellular structures and molecules for detection | High quantum yield, photostability, specific binding | Intracellular imaging, molecular tracking [1] |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Specific target recognition in flow cytometry and imaging | Conjugated with fluorochromes (e.g., FITC, PE, APC) | Immune cell phenotyping, intracellular staining [5] |

| Nanoparticles | Enhanced contrast and sensing capabilities | Metallic nanoparticles, quantum dots, photonic crystals | Biosensing, signal amplification [2] [3] |

| Photosensitizers | Light-activated therapeutic agents | High singlet oxygen yield, target specificity | Photodynamic therapy, targeted cell destruction [3] |

| Intercalating Dyes | DNA/RNA staining for cell cycle analysis | Specific binding to nucleic acids, fluorescence enhancement | Cell cycle analysis, viability assessment [5] |

| Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs) | High-sensitivity light detection | High gain, low noise, broad spectral response | Fluorescence detection, low-light imaging [2] |

| Biocompatible Optical Materials | Interfaces between light and biological tissues | Appropriate refractive index, minimal autofluorescence | Fiber optic probes, implantable sensors [2] |

Technological Integration and Emerging Frontiers

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in biophotonics is transforming data interpretation and analysis. AI-driven biophotonics techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy integrated with machine learning, have demonstrated remarkable success in recent studies [3]. For example, researchers at the University of Edinburgh were able to detect early breast cancer with a 98% accuracy using a system that identified tiny chemical changes in blood tests that other methods fail to consider [3].

AI-assisted imaging analysis contributes significantly to biological data interpretation, automated lesion detection, and real-time evaluation of therapeutic effects [2]. These capabilities have broad application value and significant impact in both preclinical and clinical research settings [2]. The implementation of AI-based image reconstruction and real-time deep learning analysis is enhancing the accessibility, affordability, and automation of see-through imaging, driving sustained market growth for these solutions [2].

Nanotechnology-Enhanced Biophotonics

Nanotechnology is enabling unprecedented control over light-matter interactions at the nanoscale, significantly improving the performance of diagnostic and therapeutic tools [3]. By employing nanomaterials including metallic nanoparticles and quantum dots, biophotonic devices achieve higher sensitivity and specificity for sensing biomarkers and tissue imaging [3]. These advancements result in earlier disease detection and more specific treatments [3].

The development of nanophotonic biosensors has facilitated ideal biosensor performance, enabling ultrasensitive tracking of DNA, proteins, and biomarkers in small volumes [2]. These technologies support enhanced disease screening, personalized medicine, and early-stage cancer detection [2]. The continuous innovation in nanotechnology applications represents a significant frontier in biophotonics research and development.

Quantum Biophotonics

Emerging quantum technologies are opening new possibilities for biophotonics applications. Quantum-inspired techniques are being developed for enhanced imaging sensitivity beyond classical limits, with potential applications in super-resolution microscopy and single-molecule detection [1]. Quantum light sources and detectors may enable new modalities for biological imaging and sensing with improved signal-to-noise ratios and reduced photodamage to living samples [1].

The preservation of orbital angular momentum in scattering media, demonstrated in 2024 experiments, shows promise for new applications in biophotonics [4]. These structured light approaches may enable more efficient light penetration through turbid biological tissues and improved information encoding in optical communication with implanted devices [4].

Biophotonics stands as a cornerstone of next-generation precision medicine and the One Health approach, integrating biological research, medical applications, environmental monitoring, and agricultural advancements [1]. The field continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advancements in light sources, detectors, computational methods, and nanofabrication [1].

Future development will likely focus on enhancing non-invasiveness, improving spatial and temporal resolution, increasing penetration depth, and developing multi-modal platforms that combine complementary techniques [1]. The growing emphasis on point-of-care devices, wearable sensors, and affordable screening technologies will further expand the accessibility and impact of biophotonics across diverse healthcare settings and resource levels [2].

As interdisciplinary collaborations between physicists, chemists, engineers, biologists, computer scientists, medical professionals, and industry stakeholders continue to strengthen, biophotonics is poised to deliver increasingly sophisticated solutions to fundamental biological questions and pressing medical challenges [1]. The transformative potential of this field remains substantial, with ongoing innovations promising to further revolutionize how we study, diagnose, and treat biological systems across the spectrum from single molecules to entire organisms.

Biophotonics, the fusion of photonics and life sciences, leverages light to analyze and manipulate biological materials [1]. This interdisciplinary field is foundational to advancements in medical diagnostics, therapeutic applications, and fundamental biological research [1]. The core of biophotonic technologies lies in understanding how light interacts with biological tissues through the fundamental processes of absorption, emission, scattering, and reflection [6] [1]. These processes determine the propagation of light within tissue, influence the design of optical instruments, and dictate the type of biological information that can be extracted [6]. Quantitative measurement of these interactions is challenging due to the complex nature of tissue, but it is essential for developing non-invasive diagnostic tools, monitoring therapies, and guiding surgical procedures [7] [8]. This guide details the core principles, quantitative parameters, and experimental methodologies for characterizing these light-tissue interactions, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals in the biophotonics field.

Fundamental Principles and Quantitative Parameters

When light is incident on biological tissue, it undergoes several interactions at the interface and within the tissue bulk. A portion of the light is reflected at the surface due to the mismatch in refractive index between air and tissue. The remaining light penetrates the tissue, where it may be transmitted, absorbed, or scattered in various directions [6] [9]. The specific outcome is governed by the optical properties of the tissue and the wavelength of the incident light.

Scattering Mechanisms

Scattering occurs when light is deflected from its original path by inhomogeneities within the tissue, such as organelles, collagen fibers, and other subcellular structures [6].

- Rayleigh Scattering: This occurs when light interacts with particles much smaller than the wavelength of light, such as very small cellular components [6]. The intensity of Rayleigh scattered light is proportional to the inverse fourth power of the wavelength ((I \propto \frac{1}{\lambda^4})) [6]. This wavelength dependence explains why shorter wavelengths (like blue light) scatter more effectively in tissue.

- Mie Scattering: This dominates when the particle size is comparable to or larger than the wavelength of light, such as in the case of mitochondria or nuclei [6]. Mie scattering is more uniform across wavelengths and is less wavelength-dependent than Rayleigh scattering [6].

- Multiple Scattering: In dense, thick tissues, light undergoes repeated scattering events, a phenomenon known as multiple scattering [6]. This results in diffuse light propagation, where light loses its original directionality [6]. Multiple scattering increases the effective optical path length of light within the tissue and complicates the analysis of light-tissue interactions, often requiring advanced modeling techniques like radiative transfer theory or Monte Carlo simulations [6].

Absorption and the Beer-Lambert Law

Absorption is the process by which chromophores in the tissue capture light energy, converting it into other forms of energy such as heat or chemical energy [9]. Key chromophores in biological tissues include hemoglobin (oxy- and deoxy-), melanin, water, lipids, and collagen [8]. The absorption coefficient ((μ_a)), defined as the probability of photon absorption per unit pathlength, quantifies this interaction [8]. Its typical order of magnitude is (0.1 \, \text{cm}^{-1}) in the near-infrared (NIR-I) window [8].

A fundamental model describing light attenuation in a medium is the Beer-Lambert Law: [ I = I0 e^{-\mua d} ] where (I) is the transmitted intensity, (I0) is the incident intensity, (\mua) is the absorption coefficient, and (d) is the path length through the medium [6]. While foundational, this law assumes negligible scattering and homogeneous absorption, which limits its direct accuracy in most biological tissues where scattering is significant [6].

Reflection and Transmission at Interfaces

When light encounters an interface between two media with different refractive indices (e.g., air and skin), a portion is reflected. The reflection coefficient (R) quantifies the fraction of incident light intensity that is reflected [6]. For normal incidence, it is calculated using Fresnel equations: [ R = \left( \frac{n1 - n2}{n1 + n2} \right)^2 ] where (n1) and (n2) are the refractive indices of the two media [6]. The remaining light is transmitted into the tissue. In non-absorbing media, the transmission coefficient is (T = 1 - R) [6].

Diffuse reflectance is a key concept in tissue optics. It occurs when light undergoes multiple scattering events within the tissue before re-emerging from the incident surface [6]. This diffused light carries information about the tissue's internal scattering and absorption properties and is widely used for non-invasive tissue characterization [6].

Emission Phenomena

Emission processes involve the re-radiation of light by a biological material after it has absorbed energy. A key emission phenomenon is fluorescence, where a chromophore (fluorophore) absorbs a high-energy photon and subsequently emits a lower-energy photon at a longer wavelength [7]. This "Stokes shift" allows the emitted light to be distinguished from the excitation light. Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) is a powerful analytical technique that uses this principle for tissue classification and molecular analysis [7]. Other emission-based phenomena include phosphorescence and second harmonic generation (SHG) [7] [1].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Quantifying Tissue Optical Properties [6] [8]

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Common Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient | (\mu_a) | Probability of photon absorption per unit pathlength | (\text{mm}^{-1}) or (\text{cm}^{-1}) |

| Scattering Coefficient | (\mu_s) | Probability of photon scattering per unit pathlength | (\text{mm}^{-1}) or (\text{cm}^{-1}) |

| Anisotropy Factor | (g) | Average cosine of the scattering angle ((⟨\cos \theta⟩)) | Unitless |

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient | (\mu_s') | (\mus' = \mus (1 - g)), represents the effective isotropic scattering | (\text{mm}^{-1}) or (\text{cm}^{-1}) |

| Refractive Index | (n) | Ratio of the speed of light in vacuum to that in the medium | Unitless |

| Effective Attenuation Coefficient | (\mu_{\text{eff}}) | (\mu{\text{eff}} = \sqrt{3\mua(\mua + \mus')}), describes attenuation in a scattering medium | (\text{mm}^{-1}) or (\text{cm}^{-1}) |

Table 2: Dominant Scattering Mechanisms and Chromophores in Biological Tissues [6] [8] [9]

| Interaction | Dominant Mechanism/Particle | Wavelength Dependence | Biological Targets/Chromophores |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rayleigh Scattering | Particles << Wavelength (e.g., small proteins) | (I \propto \frac{1}{\lambda^4}) | Very small cellular structures |

| Mie Scattering | Particles ≈ Wavelength (e.g., organelles, nuclei) | Less wavelength-dependent | Mitochondria, collagen fibers |

| Absorption in VIS | Chromophores | Varies by chromophore | Hemoglobin, Melanin |

| Absorption in NIR | Chromophores | Varies by chromophore | Water, Lipids |

| Absorption in IR | Chromophores | Varies by chromophore | Water, Hydroxyapatite |

Experimental Protocols for Measuring Optical Properties

Accurately determining the optical properties of tissues requires well-designed experiments and robust mathematical models to solve the inverse problem of relating measured light to internal properties [8].

Measurement Configurations and Instrumentation

A common setup for measuring total transmission ((T)) and diffuse reflectance ((R)) of tissue samples employs an integrating sphere coupled to a spectrometer and light source [7]. The sphere collects all light transmitted through or reflected from the sample, allowing for accurate quantification [7]. These measurements are typically performed at multiple wavelengths, for example, in the red to near-infrared spectrum (e.g., 808, 830, 980 nm) to exploit the "optical window" where tissue penetration is highest [7].

The experimental workflow can be summarized as follows:

Figure 1: Workflow for estimating tissue optical properties.

Inverse Models for Property Extraction

The measured (R) and (T) data are inputs for inverse models that compute the intrinsic optical properties.

- Kubelka-Munk (KM) Model: A widely used two-flux model that provides a simple analytical solution, directly relating (R) and (T) to the absorption ((K)) and scattering ((S)) coefficients [7]. Its simplicity is its major advantage, though it is most accurate for highly scattering and weakly absorbing samples [7].

- Inverse Adding-Doubling (IAD): This method calculates the reflectance and transmittance of a sample by iteratively adding and doubling layers until the measured values are matched, allowing for the extraction of (\mua) and (\mus) [8].

- Inverse Monte Carlo (IMC): This method uses stochastic simulations of photon transport to iteratively adjust (\mua) and (\mus) until the simulated (R) and (T) match the experimental measurements [8]. While computationally intensive, it is considered very accurate and can handle complex geometries.

- Spatial/Frequency Domain Techniques: These advanced methods analyze the spatial distribution of diffuse reflectance or the modulation and phase shift of intensity-modulated light to separate the effects of absorption and scattering [8].

Table 3: Summary of Inverse Models for Estimating Optical Properties [7] [8]

| Model/Method | Primary Inputs | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kubelka-Munk (KM) | R, T, sample thickness | Simple, analytical solution; fast computation | Less accurate for low-scattering or highly absorbing samples |

| Inverse Adding-Doubling (IAD) | R, T, sample thickness | High accuracy; works for a wide range of optical properties | Requires a layered geometry |

| Inverse Monte Carlo (IMC) | R, T, sample thickness | High accuracy; can model complex geometries | Computationally intensive and slow |

| Spatial/Frequency Domain | Spatially/temporally resolved reflectance | Can directly separate μa and μs' in vivo | Requires specialized source-detector hardware |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation in biophotonics relies on a suite of essential materials and instruments. The following table details key components of a research toolkit for studying light-tissue interactions.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Biophotonics Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Integrating Sphere | Collects all light transmitted through or reflected from a sample, enabling accurate measurement of total diffuse reflectance (R) and transmittance (T) [7]. |

| Miniature Spectrometer | Resolves the wavelength composition of light, used for acquiring fluorescence, reflectance, and transmittance spectra [7]. |

| DPSS Lasers | (Diode-Pumped Solid-State Lasers) provide high-intensity, monochromatic light sources for excitation in techniques like LIF and for probing tissue optical properties [7]. |

| Tissue-Mimicking Phantoms | Standardized materials with known optical properties (e.g., using Intralipid for scattering, India ink for absorption) used for system calibration and validation of models [8]. |

| Digital Micrometer | Precisely measures sample thickness, a critical parameter for accurate inversion of optical properties using models like KM and IAD [7]. |

| Optical Fiber Probes | Deliver light to the sample and collect emitted or reflected light, enabling flexible experimental configurations and in-situ measurements [7]. |

| Kubelka-Munk Model | A mathematical transport model used to directly calculate absorption and scattering coefficients from measured R and T values [7]. |

Visualization of Light-Tissue Interactions and Data Analysis

Understanding the journey of light through tissue and the subsequent data analysis is crucial for interpreting experimental results. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental physical processes and the parallel workflow for analytical modeling.

Figure 2: Light-tissue interaction processes and analytical workflow.

Biophotonics, defined as the interdisciplinary fusion of light-based technologies with biology and medicine, uses the properties of photons to analyze and manipulate biological materials [1]. This field leverages the fundamental interactions between light and biological matter—including absorption, emission, reflection, and scattering—to advance our understanding of life processes at the molecular, cellular, tissue, and organ levels [1]. Among its many capabilities, three core advantages make biophotonics a transformative technology in life sciences and medical diagnostics: non-invasiveness, high sensitivity, and real-time measurement. These characteristics allow researchers and clinicians to observe biological processes in their native state, detect minute quantities of analytes, and monitor dynamic events as they unfold, thereby providing a powerful toolkit for biomedical research, drug development, and clinical diagnostics.

The non-contact nature of optical measurements allows for the observation of living cells and tissues without compromising their integrity, thereby preserving biological function and enabling longitudinal studies in vivo [1]. The sensitivity of biophotonic techniques can reach the level of single molecules, which is essential for understanding fundamental biological processes and detecting early disease biomarkers [1]. Furthermore, the speed of light enables optical technologies to provide rapid, real-time data, significantly reducing the time required for data interpretation and diagnosis [1]. This combination of attributes positions biophotonics as a cornerstone technology for next-generation precision medicine and the One Health approach, with applications spanning oncology, infectious diseases, neurology, cardiovascular health, and beyond [1].

Non-Invasiveness in Biophotonic Technologies

Fundamental Principles and Biological Interactions

The non-invasive character of biophotonics stems from the ability of light, particularly wavelengths in the near-infrared window, to penetrate biological tissues with minimal damage or disruption. This property enables researchers to probe living systems without physical contact or the need for exogenous labels in many cases, preserving the integrity of the biological specimen under investigation [1]. Label-free techniques such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), vibrational microspectroscopy (infrared and Raman scattering), and second harmonic generation (SHG) leverage inherent optical properties of tissues to generate contrast, allowing for repeated measurements over time without cumulative toxic effects [1].

Techniques based on nonlinear optical phenomena, such as multi-photon microscopy, are particularly valuable for non-invasive deep tissue imaging. The simultaneous absorption of two or three photons leads to precise localization of signal sources since such nonlinear processes only occur in an extremely small volume, thereby minimizing out-of-focus photodamage and allowing for high-resolution imaging deep within living tissues [1]. This capability has revolutionized the study of dynamic biological processes in their native context, from neural activity in the brain to immune cell trafficking in tumors.

Applications in Live-Cell and In-Vivo Imaging

Non-invasive biophotonic imaging has become indispensable for studying infectious diseases in animal models, where the same group of animals can be imaged repeatedly throughout an experiment [10]. This approach significantly refines animal models by allowing each animal to serve as its own control, reducing biological variability, and providing extremely accurate data on disease progression [10]. Furthermore, the appearance of specific photonic signals can serve as early indicators of disease outcomes, enabling humane intervention before the onset of clinical symptoms [10].

In clinical settings, non-invasive biophotonic techniques are transforming diagnostic paradigms. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides label-free, high-resolution optical imaging with sufficient sampling frequency for intraoperative evaluation, functioning as an "optical biopsy" that generates images comparable to histological sections without tissue removal [11]. Similarly, breath analysis using laser absorption spectroscopy and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy detects volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as biomarkers for diseases including tuberculosis, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and even mental disorders like schizophrenia [12]. These approaches offer completely non-invasive diagnostic avenues that could potentially replace or supplement conventional invasive procedures.

High Sensitivity of Biophotonic Methods

Technological Foundations of Sensitivity

The exceptional sensitivity of biophotonic methods arises from advanced detector technologies and sophisticated signal amplification strategies. Sensitive photon detectors based on cooled or intensified charge-coupled device (CCD) cameras can detect extremely dim light signals emitted from within living organisms [10]. These systems operate by detecting visible light that arises from either the excitation of fluorescent molecules or from enzyme-catalyzed oxidation reactions (bioluminescence), enabling researchers to observe and quantify the spatial and temporal distribution of light production from within living animals [10].

The development of biophotonic probes from natural materials and biological entities represents a significant advancement in sensitive detection. Biological lasers (biolasers), which utilize naturally derived biomaterials as part of the laser cavity and/or gain medium, can serve as highly sensitive probes for detecting biological signals at molecular, cellular, and tissue levels [13]. Compared to traditional fluorescence emission, lasing probes exhibit much narrower linewidth, stronger light intensity, higher sensitivity, and superior spectral and spatial resolution due to unique optical feedback mechanisms and threshold characteristics [13]. Similarly, nanophotonic biosensors that incorporate plasmonic nanoparticles, quantum dots, and photonic crystals enable ultrasensitive tracking of DNA, proteins, and biomarkers in minute volumes, facilitating enhanced disease screening and early-stage cancer detection [2].

Single-Molecule and Single-Cell Detection

The sensitivity of biophotonic technologies extends to the ultimate limit of detection—single molecules. Optical technologies allow for ultrasensitive detection down to single molecules, which is essential for understanding fundamental biological processes [1]. This capability has been demonstrated in techniques such as fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy, and zero-mode waveguides, enabling researchers to observe biochemical reactions and molecular interactions at previously inaccessible resolutions.

At the cellular level, biophotonic flow cytometry and imaging flow cytometry combine the statistical power of conventional flow cytometry with the detailed imagery of microscopy, allowing for high-throughput analysis and sorting of individual cells based on both phenotypic and morphological characteristics. These technologies have become indispensable tools in immunology, cancer biology, and stem cell research, where rare cell populations must be identified and isolated from complex mixtures with high precision and recovery rates.

Table 1: Quantitative Sensitivity Metrics of Selected Biophotonic Technologies

| Technology | Detection Limit | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Molecule Spectroscopy | Single molecules | <10 nm | Milliseconds | Protein folding, enzyme kinetics, molecular interactions |

| Biolasers | ~100 molecules in microcavity [13] | Diffraction-limited | Nanoseconds | Intracellular sensing, biomarker detection |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy | Single molecules | ~20 nm | Seconds | VOC detection, pathogen identification [12] |

| Cooled CCD Imaging | <100 photons/sec/cm²/steradian [10] | 20-100 μm (in vivo) | Seconds to minutes | Bioluminescence imaging, infectious disease tracking [10] |

| Multiphoton Microscopy | ~100 fluorescent molecules | ~300 nm | Microseconds to seconds | Deep tissue imaging, neuronal activity |

Real-Time Measurement Capabilities

Technologies Enabling Real-Time Monitoring

Real-time measurement represents one of the most significant advantages of biophotonic technologies, stemming from the inherent speed of light and the development of high-speed detectors. Optical measurements provide rapid, real-time data, significantly reducing the time required for data interpretation and diagnosis [1]. This capability allows researchers to monitor biological processes as they unfold, rather than inferring dynamics from static snapshots. Technologies such as fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM), Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), and total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy provide insights into molecular interactions, conformational changes, and cellular signaling events with temporal resolutions ranging from hours to ultrafast reactions [1] [14].

The integration of biophotonics with microfluidic systems has further enhanced real-time monitoring capabilities, particularly in the context of high-throughput screening and diagnostics. Lab-on-a-chip platforms incorporating optical biosensors enable continuous monitoring of cellular responses, enzyme activities, and molecular interactions with millisecond temporal resolution. These systems are particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research, where real-time assessment of compound effects on cellular models can accelerate drug discovery and reduce development costs.

Dynamic Process Monitoring in Research and Clinical Settings

In infectious disease research, real-time biophotonic imaging has transformed our understanding of host-pathogen interactions. The nondestructive nature of biophotonic imaging allows the course of an infection to be monitored by imaging the photonic signal detected from within the same group of animals over time [10]. This approach provides unprecedented accuracy in tracking disease progression, from initial colonization through dissemination and, ultimately, to resolution or lethal outcome. Importantly, real-time imaging can immediately detect errors in inoculation administration, allowing researchers to eliminate affected animals from studies—thus minimizing potential suffering and reducing flawed scientific data [10].

In clinical environments, real-time biophotonic technologies are being integrated into surgical and diagnostic workflows. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is one of the fastest methods in terms of volume elements imaged per second, enabling real-time 3D imaging of dynamic processes [1]. This capability has established OCT as a gold standard in ophthalmology and is increasingly being applied in interventional cardiology and oncology. Similarly, rapid evidential breath analyzers based on laser absorption spectroscopy are being developed for point-of-care detection of infections and metabolic disorders, providing results in minutes rather than the hours or days required for conventional culture-based or laboratory tests [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Non-Invasive Biophotonic Imaging of Infection Dynamics

This protocol outlines the methodology for tracking infectious disease progression in live animal models using biophotonic imaging, based on established practices in the field [10].

Principle: Pathogens engineered to express luciferase or fluorescent proteins can be detected and quantified non-invasively in living animals using sensitive photon detectors. The light signal produced is proportional to pathogen burden, allowing for real-time monitoring of infection dynamics.

Materials:

- Bioluminescent or fluorescent pathogen strain (e.g., luxCDABE-transfected bacteria)

- Appropriate animal model (e.g., mouse)

- Cooled CCD camera system mounted in light-tight chamber

- Anesthesia system (e.g., isoflurane vaporizer)

- Depilatory cream for hair removal

- Living Image or equivalent image analysis software

- Sterile PBS for inoculum preparation

Procedure:

- Preparation of Inoculum:

- Grow bioluminescent pathogens to mid-log phase.

- Wash and resuspend in sterile PBS to desired concentration.

- Confirm luminescence using plate reader or preliminary imaging.

Animal Preparation:

- Anesthetize animal using appropriate anesthetic (e.g., 2-3% isoflurane).

- Remove hair from imaging area using depilatory cream to minimize light absorption.

- Administer pathogen via appropriate route (e.g., intranasal, intravenous, intraperitoneal).

Image Acquisition:

- Place anesthetized animal in light-tight imaging chamber.

- Maintain anesthesia throughout imaging procedure.

- Acquire series of images with varying exposure times (typically 30 seconds to 5 minutes).

- Include uninjected control animal to assess background luminescence.

- For fluorescence imaging, select appropriate excitation and emission filters.

Data Analysis:

- Use imaging software to quantify total photon flux (photons/sec/cm²/steradian) within regions of interest.

- Normalize signals to background levels from control animals.

- Generate kinetic curves of pathogen burden by repeated imaging of the same animals over time.

- Correlate bioluminescence signals with conventional metrics (e.g., colony-forming units from homogenized tissues).

Troubleshooting:

- Low signal may require increased exposure time or use of more sensitive camera.

- High background may indicate incomplete removal of hair or contamination.

- Signal saturation can be addressed by reducing exposure time or camera binning.

Protocol: Real-Time VOC Detection in Breath Samples

This protocol describes the detection of volatile organic compounds in breath for non-invasive disease diagnosis using biophotonic technologies [12].

Principle: Disease-specific volatile organic compounds present in exhaled breath can be detected and quantified using laser absorption spectroscopy or surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy, providing a non-invasive diagnostic approach.

Materials:

- Laser absorption spectrometer or surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy system

- Breath collection apparatus (e.g., Bio-VOC sampler)

- Nanostructured metal surfaces for SERS (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles)

- Calibrated gas standards for target VOCs

- Data analysis software with machine learning capabilities

Procedure:

- Sample Collection:

- Instruct subject to exhale normally, then collect alveolar breath using specialized sampler.

- Transfer breath sample immediately to analysis chamber.

- For SERS analysis, preconcentrate VOCs on nanostructured surfaces.

Instrument Setup:

- For laser absorption spectroscopy: tune laser to absorption wavelength of target VOC.

- For SERS: functionalize nanostructures with selective capture agents if necessary.

- Calibrate instrument using certified gas standards at known concentrations.

Measurement:

- Direct breath sample through flow cell for laser absorption measurements.

- For SERS, expose functionalized nanoparticles to breath sample and acquire spectra.

- Perform multiple technical replicates for statistical robustness.

- Include control samples from healthy subjects for comparison.

Data Analysis:

- For laser absorption: quantify VOC concentration based on Beer-Lambert law.

- For SERS: identify characteristic Raman peaks of target VOCs.

- Apply machine learning algorithms to spectral data for pattern recognition.

- Generate classification models to distinguish disease states based on VOC profiles.

Validation:

- Compare biophotonic results with gold standard diagnostic methods.

- Assess sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy using receiver operating characteristic curves.

- Determine limit of detection and quantitative range for each target VOC.

Visualization of Biophotonic Concepts and Workflows

Technology Relationship Diagram

Diagram 1: Fundamental workflow of biophotonic systems and their core advantages. The diagram illustrates how light interacts with biological samples to generate detectable signals, with each stage enabled by specific technological advantages.

In-Vivo Infection Imaging Workflow

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for non-invasive biophotonic imaging of infections. The process highlights how core advantages integrate at specific stages to enable longitudinal monitoring of disease progression in live animals.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biophotonic Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luciferase Enzymes | Catalyzes light-producing oxidation reactions | In vivo bioluminescence imaging, reporter gene assays | Requires substrate (e.g., D-luciferin); different luciferases vary in emission wavelength and kinetics |

| Fluorescent Proteins (GFP, RFP, etc.) | Genetic encoding of fluorescence | Cell tracking, gene expression monitoring, protein localization | Photostability, maturation time, and oligomerization state vary between variants |

| Quantum Dots | Nanocrystals with bright, tunable fluorescence | Long-term cell tracking, multiplexed detection, in vivo imaging | Potential cytotoxicity; surface coating critical for biocompatibility |

| SERS Nanoparticles | Enhances Raman scattering signals | Ultrasensitive detection, VOC profiling, multiplexed assays | Composition (Au, Ag) and morphology affect enhancement factors |

| Bioluminescent Substrates | Fuel for luciferase-mediated light production | In vivo imaging, ATP detection, cytotoxicity assays | Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability affect in vivo applications |

| Near-Infrared Dyes | Fluorescent probes with deep tissue penetration | In vivo imaging, surgical guidance, perfusion assessment | Spectral overlap with tissue autofluorescence must be considered |

| Optical Clearing Agents | Reduce light scattering in tissues | Deep tissue imaging, whole-organ microscopy | Must balance clearing efficacy with preservation of fluorescence |

| Functionalized Biosensors | Detect specific analytes or enzymatic activities | Metabolite monitoring, protease activity, pH sensing | Specificity, dynamic range, and response time are critical parameters |

The synergistic combination of non-invasiveness, high sensitivity, and real-time measurement establishes biophotonics as an indispensable technology platform for biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. These core advantages enable researchers to interrogate biological systems with minimal perturbation, detect increasingly subtle molecular signals, and observe dynamic processes as they unfold in living systems. As biophotonic technologies continue to evolve—driven by advances in laser sources, detector technologies, nanophotonics, and computational analytics—their impact will expand across diverse fields including basic research, drug discovery, clinical diagnostics, and personalized medicine. The integration of artificial intelligence with biophotonic systems promises to further enhance analytical capabilities, enabling automated interpretation of complex data and potentially uncovering novel biological insights that would otherwise remain obscured. With continuous technological innovation and growing adoption across life sciences and medicine, biophotonics is poised to remain at the forefront of scientific discovery and medical advancement for the foreseeable future.

Biophotonics, the fusion of light-based technologies with biology and medicine, is a cornerstone of 21st-century scientific innovation, revolutionizing research, diagnostics, and therapy [1]. This discipline leverages the properties of light to analyze and manipulate biological materials, enabling unprecedented precision in measuring and understanding life processes from the molecular to the organ level [1]. The core advantages of using light in biomedical applications include its capacity for non-contact measurement, which preserves the integrity of living cells; high sensitivity, allowing for detection down to single molecules; and superior time resolution, facilitating the observation of dynamic biological processes in real-time [1].

The field of biophotonics can be broadly divided into three main technological areas:

- Bioimaging: Photonics enables the characterization of biological specimens across multiple spatial scales, from nanoscopic intracellular interactions to macroscopic tissues [1].

- Biosensing: Photonic-based approaches allow for the detection of biomolecules, such as disease-specific biomarkers, with extreme sensitivity [1].

- Photonic Therapy: Lasers and other light sources facilitate highly precise and minimally invasive surgical interventions and treatments, with bioimaging and biosensing enabling real-time monitoring of efficacy [1].

Central to all these applications is the interaction between light and biological matter, primarily through processes of absorption, emission, scattering, and reflection. The choice of light source is critical, as it determines the specificity, depth, and resolution of the interaction. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the three essential light sources—Lasers, Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs), and Superluminescent Diodes (SLEDs)—that power modern biophotonics.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

The operational principles of Lasers, LEDs, and SLEDs define their unique output characteristics and, consequently, their suitability for specific biomedical applications.

Lasers (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) operate on the principle of stimulated emission [15]. They produce highly coherent, monochromatic light with a narrow spectral bandwidth and high optical power density [15]. This coherence, while beneficial for focusing light to a small spot, leads to significant speckle—a grainy interference pattern that can degrade image quality in certain imaging systems [15].

Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) generate light through electroluminescence and spontaneous emission [15]. They are incoherent sources that emit a broad spectrum of light, resulting in low optical power density and very short coherence lengths [15] [16]. This inherent incoherence makes them immune to speckle noise.

Superluminescent Diodes (SLEDs or SLDs) bridge the gap between lasers and LEDs. They function similarly to laser diodes but are designed to suppress optical feedback, producing amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) [15] [17]. This results in a combination of laser-like properties (such as high output power and high spatial coherence) with LED-like properties (broad spectral bandwidth and low temporal coherence) [15] [17]. This unique combination minimizes speckle while maintaining high intensity, making SLEDs ideal for high-precision imaging [15].

Table 1: Fundamental Operating Principles of Lasers, LEDs, and SLEDs.

| Feature | Laser (LD) | Superluminescent Diode (SLED) | Light Emitting Diode (LED) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Principle | Stimulated Emission | Amplified Spontaneous Emission (ASE) | Spontaneous Emission |

| Light Coherence | High (Coherent) | Medium (Low Temporal Coherence) | Low (Incoherent) |

| Spectral Bandwidth | Narrow (several nm or less) [16] | Medium (10-50 nm) [16] | Broad (up to ~100 nm) [16] |

| Optical Output Power | High (several hundred mW) [16] | Medium (tens of mW) | Low [15] |

| Coherence Length | Long (several dozen cm to meters) [16] | Short (~40-50 µm) [16] | Very Short (up to ~20 µm) [16] |

| Speckle Effect | High [15] | Low [15] | None |

Table 2: Summary of Key Characteristics and Biomedical Applications.

| Characteristic | Laser | SLED | LED |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Nature | Narrowband, coherent | Broadband, low coherence | Broadband, incoherent |

| Power Density | High [15] | Medium [15] | Low [15] |

| Primary Biomedical Applications | Laser surgery, skin treatments, flow cytometry, DNA sequencers [15] | Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), fiber-optic sensors [17] | Phototherapy (e.g., acne, jaundice, wound healing), photo rejuvenation [18] [19] |

| Key Advantages in Biomedicine | High precision, ability to deliver high energy for ablation and surgery | High resolution in imaging due to broadband source, reduced speckle [15] | Safety, low cost, ability to treat large areas, portability [19] |

Lasers in Biomedicine

Key Applications and Experimental Protocols

Lasers are indispensable tools in therapeutic and diagnostic applications requiring high precision and power.

- Laser Surgery and Skin Treatments: Lasers are used for highly precise and minimally invasive surgical procedures, including skin resurfacing and the treatment of various skin lesions [15] [1]. The protocol involves selecting a specific wavelength (e.g., Er:YAG for ablation) and pulse duration to match the absorption characteristics of the target tissue (e.g., water for soft tissue), thereby minimizing collateral damage to surrounding areas.

- Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) for Oncology: This treatment involves administering a photosensitizing drug (e.g., Aminolevulinic Acid - ALA or its ester, MAL) that accumulates preferentially in target cells, such as cancer cells [18]. The target area is then irradiated with a specific wavelength of laser light (e.g., red light at 633 nm for deep penetration), which activates the drug, triggering a photochemical reaction that generates cytotoxic reactive oxygen species and destroys the target cells [18]. Clinical studies have shown high efficacy, with one study reporting a 95% response rate for MAL-PDT in treating Bowen's disease [18].

- Advanced Bioimaging: Non-linear laser microscopy techniques, such as Multi-Photon Microscopy, leverage high-intensity, ultrashort-pulsed lasers (e.g., Ti:Sapphire) to enable high-resolution imaging deep within scattering biological tissues [1]. The simultaneous absorption of two or three photons provides precise spatial localization, allowing for the study of dynamic processes in live cells and tissues with minimal photodamage and out-of-focus bleaching.

Diagram 1: Laser experiment workflow.

Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) in Biomedicine

Key Applications and Experimental Protocols

LEDs have emerged as a safe, cost-effective, and versatile light source for a range of therapeutic applications, particularly in dermatology and regenerative medicine.

- Blue LED for Acne Treatment: Blue light (around 415 nm) is used to treat acne vulgaris through a natural photodynamic effect [18]. The protocol involves irradiating the affected skin area with blue LED light. The light is absorbed by endogenous porphyrins (mainly coproporphyrin III) produced by Propionibacterium acnes, which generates cytotoxic singlet oxygen and other free radicals, leading to bacterial destruction and a reduction in inflammation [18]. A typical clinical protocol might involve treatments twice weekly for several weeks [18].

- Red and Near-Infrared LED for Wound Healing and Photobiomodulation: Red (630-700 nm) and infrared (800-1200 nm) LEDs are used to accelerate wound healing and reduce inflammation [18]. The proposed mechanism involves the absorption of light by mitochondrial chromophores (e.g., cytochrome c oxidase), leading to increased ATP production, modulation of reactive oxygen species, and the induction of transcription factors that promote tissue repair and angiogenesis [18]. A sample experimental methodology for a rodent wound healing model would involve creating standardized wounds, followed by daily irradiation with a red LED (e.g., 670 nm) at a specific power density (e.g., 50 mW/cm²) and energy density (e.g., 4 J/cm²), with wound size measured regularly until closure [18].

- LED-based Phototherapy for Neurological and Mood Disorders: Narrow-band blue LED light has been investigated for treating Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) by helping to regulate circadian rhythms [19]. The treatment involves daily exposure to a blue LED light source, which influences melatonin production and serotonin levels, thereby improving mood and alertness.

Table 3: LED-Based Phototherapy Parameters for Common Applications.

| Condition | LED Wavelength | Typical Parameters | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne Vulgaris [18] | Blue (415 nm) | 40-50 J/cm², twice weekly | Activation of bacterial porphyrins, leading to bacterial destruction via reactive oxygen species. |

| Skin Rejuvenation & Wound Healing [18] | Red (633 nm) | 50-200 mW/cm², 1-5 J/cm², daily | Stimulation of fibroblast activity, increased collagen production, and enhanced cellular metabolism. |

| Wound Healing (Deep Tissue) [18] | Near-Infrared (830 nm) | N/A | Stimulation of circulation, angiogenesis, and growth factor production. |

| Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) [19] | Blue (~470 nm) | Daily exposure sessions | Regulation of circadian rhythm via suppression of melatonin and modulation of serotonin. |

Superluminescent Diodes (SLEDs) in Biomedicine

Key Applications and Experimental Protocols

SLEDs find their niche in high-resolution biomedical imaging and sensing applications where their unique combination of high spatial coherence and broad bandwidth is critical.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): This is the foremost application of SLEDs in biomedicine [17]. OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique that captures micrometer-resolution, three-dimensional images from within optical scattering media, such as biological tissue [17]. The broad bandwidth of the SLED light source directly determines the axial resolution of the system; a broader spectrum yields finer resolution [17]. The protocol involves splitting the SLED's broadband light into a sample arm and a reference arm. The light reflected from the sample and the reference mirror is recombined, and the resulting interference pattern is analyzed to construct a depth profile (A-scan). By scanning the beam across the sample, a 2D or 3D image (B-scan) is generated [17]. Frequency-domain OCT, which uses a spectrally scanning SLED source and calculates the depth scan via a Fourier transform, has dramatically improved imaging speed and is now widely established in ophthalmology for retinal imaging and in cardiology for intravascular diagnostics [1] [17].

- White-Light Interferometry for Surface Metrology: SLEDs are used as broadband sources in interferometers to measure the surface topology of materials, including biological specimens and medical implants [17]. The system works by finding the position of zero optical path difference between the sample and reference beams, which results in a localized interference fringe. This allows for highly precise, non-contact measurements of surface roughness and shape.

- Fiber-Optic Sensing: SLEDs are ideal light sources for various fiber-optic sensors, including those measuring strain, temperature, and pressure in harsh biological or environmental conditions [17]. For example, in a Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensor, the broad spectrum of the SLED is used to interrogate a grating written into an optical fiber. Changes in strain or temperature shift the reflected wavelength, which can be detected and quantified [17].

Diagram 2: SLED-based OCT system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Biophotonics Research.

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Aminolevulinic Acid (ALA) / Methyl Aminolevulinate (MAL) | Topical photosensitizers used in Photodynamic Therapy (PDT). Metabolized in the target cells to form protoporphyrin IX, which is activated by laser or LED light to produce cytotoxic effects [18]. |

| Exogenous Porphyrins (e.g., Protoporphyrin IX) | Naturally occurring molecules in bacteria that act as endogenous photosensitizers for blue LED acne therapy [18]. |

| Cell Viability Assays (e.g., MTT Assay) | Used to quantify the therapeutic or cytotoxic effects of light-based treatments on cell cultures in vitro. |

| Specific Culture Media for P. acnes | Used to culture the bacteria for in vitro studies validating the efficacy of blue LED antimicrobial photodynamic therapy [18]. |

| Animal Models (e.g., Rodent Wound Model) | Preclinical in vivo models for studying the effects of LED photobiomodulation on wound healing, inflammation, and tissue regeneration [18]. |

| Optical Phantoms | Tissue-simulating materials with controlled optical properties (scattering and absorption coefficients) used to calibrate and validate imaging systems like OCT before use on biological samples. |

| Fibroblast Cell Lines | Commonly used in vitro models to study the effects of red and infrared LED light on collagen synthesis, proliferation, and other wound-healing pathways [18]. |

Lasers, LEDs, and Superluminescent Diodes each provide a distinct set of optical properties that make them uniquely suited for specific applications within the rapidly expanding field of biophotonics. The global biophotonics market, valued at $62.6 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $113.1 billion by 2030, is a testament to the transformative impact of these technologies on healthcare and life sciences [20]. The convergence of these light sources with artificial intelligence, novel materials, and quantum sensing promises to further redefine the boundaries of precision medicine, fundamental biological research, and the "One Health" approach, solidifying biophotonics as a cornerstone of future medical and scientific progress [1].

Biophotonics is an interdisciplinary field at the intersection of photonics and biology that involves the study of light interaction with biological matter, as well as the development and application of optical techniques for biological research and medicine [21]. This field leverages the properties of photons—particles of light—to probe, image, manipulate, and treat biological systems across scales from single molecules to entire organisms. The scope of biophotonics research is vast, encompassing fundamental studies of biological structure and function, development of novel diagnostic tools, discovery of new drugs, and creation of advanced therapeutic modalities.

Within this expansive field, three particularly promising areas have emerged: bioluminescence, biofluorescence, and biolasers. These technologies represent a continuum of sophistication in harnessing light for biological applications. Bioluminescence utilizes naturally occurring biochemical reactions to produce light without external excitation. Biofluorescence, while also endogenous, requires external light excitation for emission. Biolasers represent the most advanced frontier, incorporating biological materials or entire biological systems into laser cavities to generate coherent, highly directional light with unique properties for sensing and imaging. Together, these technologies are revolutionizing how researchers detect, monitor, and understand biological processes, offering unprecedented sensitivity, specificity, and temporal resolution for scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

Bioluminescence: Nature's Inner Light

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Bioluminescence is the fascinating natural phenomenon by which living organisms produce and emit light through biochemical reactions [22]. This process occurs when the oxidation of a small-molecule luciferin is catalyysed by an enzyme luciferase to form an excited-state species that emits light [22]. Unlike fluorescence, bioluminescence does not require the absorption of sunlight or other external electromagnetic radiation to generate light, which eliminates issues with sample autofluorescence, quenching, and heating [23]. The bioluminescence reaction generally requires a luciferase enzyme, its luciferin substrate, and an oxidant (typically molecular oxygen), with some systems additionally requiring energy cofactors such as ATP [22].

The firefly (Photinus pyralis) bioluminescence system represents one of the most thoroughly characterized and widely utilized luciferase-luciferin pairs. In this system, the 62 kDa insect luciferase (FLuc) catalyses the oxidation of D-luciferin in two distinct steps: first, the carboxyl group of D-luciferin is activated through adenylation by ATP; second, the resulting luciferyl-adenylate intermediate is oxidized to form an excited-state oxyluciferin species through a dioxetanone intermediate [22]. The excited-state oxyluciferin relaxes to its ground state by emitting a photon of light, typically in the yellow-green region (peak ~560 nm) [24]. This system achieves a remarkably high quantum yield of up to 41% at optimal pH conditions [22].

Figure 1: Firefly bioluminescence mechanism involving luciferyl-adenylate intermediate formation and subsequent light emission.

Major Bioluminescent Systems and Their Characteristics

While over 30 distinct bioluminescent systems exist in nature, the luciferin-luciferase pairs of only about 11 systems have been characterized to date [22]. The most widely utilized systems in research include D-luciferin-dependent systems (from fireflies and click beetles), coelenterazine-dependent systems (from marine organisms), and bacterial bioluminescent systems [23]. Each system possesses unique characteristics that make it suitable for specific applications.

D-luciferin-dependent systems are found in various lineages of beetles including fireflies, click beetles, and railroad worms [23]. These systems typically emit light across yellow, orange, and in some cases, red wavelengths [23]. The firefly luciferase system is particularly valuable because its dependence on ATP enables its application in studies of cellular metabolism and energy status [23]. Click beetle luciferases offer additional versatility, with natural variants emitting different colors ranging from green (540 nm) to orange-red (593 nm) without modification [23].

Coelenterazine-dependent systems represent the most widespread bioluminescent system in marine ecosystems, found in organisms including the sea pansy Renilla reniformis, the copepod Gaussia princeps, and the decapod shrimp Oplophorus gracilirostris [23]. These systems do not require ATP and typically emit blue light between 450-500 nm [23]. The engineered Oplophorus luciferase (NanoLuc) represents a particularly advanced system with exceptional brightness, small size (19 kDa), and high stability, making it ideal for numerous research applications [23] [24].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Bioluminescent Systems Used in Research

| Luciferase | Source Organism | Luciferin | Size (kDa) | Emission Maximum | Cofactors | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly Luciferase (FLuc) | Photinus pyralis | D-luciferin | 61 | 560 nm | ATP, Mg²⁺, O₂ | ATP sensing, in vivo imaging, reporter assays |

| Click Beetle Luciferase (CBR) | Pyrophorus plagiophthalamus | D-luciferin | 61 | 538-615 nm | ATP, Mg²⁺, O₂ | Multiplexed imaging, reporter assays |

| Renilla Luciferase (RLuc) | Renilla reniformis | Coelenterazine | 36 | 480 nm | O₂ | Dual-reporter assays, BRET |

| Gaussia Luciferase (GLuc) | Gaussia princeps | Coelenterazine | 20 | 473 nm | O₂ | Secreted reporter assays, high-throughput screening |

| NanoLuc Luciferase | Oplophorus gracilirostris | Furimazine | 19 | 460 nm | O₂ | Protein-protein interactions, high-sensitivity detection |

| Bacterial Luciferase | Photorhabdus luminescens | Fatty aldehyde | >200 | 490 nm | FMNH₂, O₂ | Bacterial labeling, continuous light production |

Research Applications and Experimental Protocols

Bioluminescence has become an indispensable tool across diverse research areas due to its exceptional sensitivity, low background, and compatibility with living systems. Key applications include gene expression reporter assays, in vivo imaging in small animal models, protein-protein interaction studies using techniques such as Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET), and high-throughput drug screening [22] [24].

Protocol: Bioluminescent Reporter Gene Assay for Gene Expression Monitoring

Principle: Cells are transfected with a plasmid in which the gene of interest controls expression of a luciferase reporter. Luciferase activity directly correlates with transcriptional activity of the gene being studied [24].

Materials:

- Mammalian cells expressing luciferase reporter construct

- Appropriate luciferin substrate (D-luciferin for firefly systems, coelenterazine for marine systems)

- Cell culture medium and reagents

- Luminometer or cooled CCD camera for detection

- Lysis buffer (for endpoint assays)

- White-walled multiwell plates (to minimize cross-talk)

Procedure:

- Seed cells in multiwell plates and transfert with luciferase reporter construct

- Allow 24-48 hours for gene expression

- For endpoint assays: lyse cells with passive lysis buffer

- Add appropriate luciferin substrate to cells or lysate

- Measure light output immediately using luminometer or imaging system

- Normalize results to protein concentration or cell number

Critical Considerations:

- For firefly luciferase assays, include ATP and Mg²⁺ in assay buffer

- For live-cell kinetic measurements, use specialized media formulations that maintain cell viability while supporting bioluminescence reaction

- Consider substrate permeability when working with different luciferase systems

- For dual-reporter assays, ensure spectral separation of signals or use sequential measurement protocols

Protocol: In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging of Tumor Growth in Mouse Models

Principle: Luciferase-expressing cells (e.g., tumor cells) are introduced into animal models. After administration of luciferin substrate, light emission is detected externally using a sensitive CCD camera, allowing non-invasive monitoring of cell proliferation and localization [24].

Materials:

- Luciferase-expressing cells (e.g., tumor cells transduced with lentiviral luciferase construct)

- Immunocompromised mice (e.g., nude or SCID mice)

- D-luciferin solution (15 mg/mL in PBS, sterile-filtered)

- Anesthesia system (isoflurane or injectable anesthetics)

- In vivo bioluminescence imaging system (e.g., IVIS Spectrum)

- Heating pad to maintain body temperature during imaging

Procedure:

- Establish tumors by injecting luciferase-expressing cells into appropriate site

- Allow tumors to establish (typically 1-4 weeks)

- Inject mice intraperitoneally with D-luciferin (150 mg/kg body weight)

- Anesthetize mice and place in imaging chamber

- Acquire images 10-20 minutes post-injection (peak signal time)

- Quantify total flux (photons/second) in region of interest

- Image repeatedly over time to monitor tumor progression

Critical Considerations:

- Optimize luciferin dose and timing for specific experimental setup

- Maintain consistent positioning and anesthesia depth between imaging sessions

- Consider substrate distribution kinetics when interpreting temporal patterns

- Account for potential effects of fur pigmentation on light attenuation

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Common Bioluminescent Reporters

| Reporter System | Detection Sensitivity | Dynamic Range | Half-life | Quantum Yield | Molar Brightness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly Luciferase | 10⁻¹⁸ - 10⁻²⁰ moles | 6-8 orders of magnitude | ~3 hours | 0.41 | High |

| Renilla Luciferase | 10⁻¹⁷ - 10⁻¹⁹ moles | 5-7 orders of magnitude | ~4 hours | 0.05-0.10 | Moderate |

| Gaussia Luciferase | 10⁻¹⁸ - 10⁻²⁰ moles | 6-8 orders of magnitude | ~6 days (secreted) | 0.10-0.15 | High |

| NanoLuc Luciferase | 10⁻¹⁹ - 10⁻²¹ moles | >7 orders of magnitude | >6 hours | ~0.30 | Very High |

Biofluorescence: Harnessing Nature's Light Absorbers

Principles and Comparison with Bioluminescence

Biofluorescence differs fundamentally from bioluminescence in its mechanism of light production. While bioluminescence generates light through biochemical reactions, fluorescence requires the absorption of external light at specific wavelengths followed by emission at longer wavelengths [25]. This process occurs when a fluorophore absorbs photons, elevating electrons to an excited state, followed by relaxation back to ground state with emission of lower-energy photons [25].