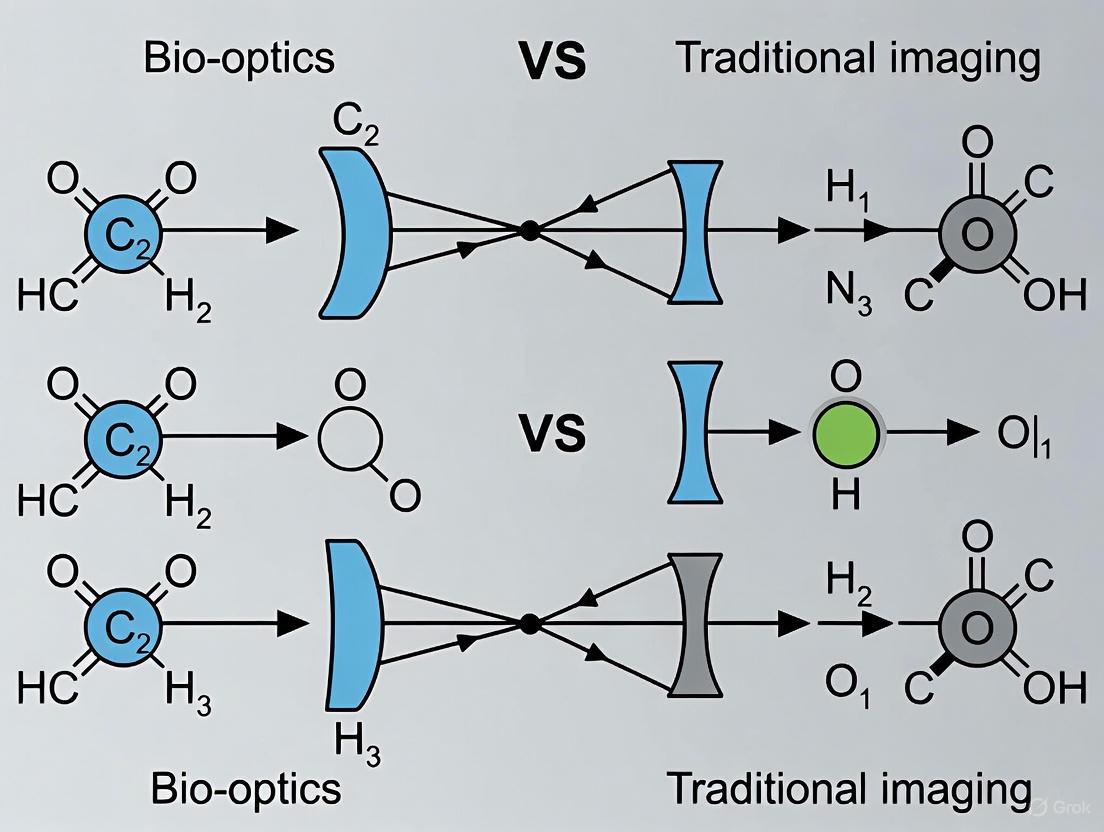

Bio-Optics vs. Traditional Imaging: A Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between bio-optics—the convergence of light-based technologies with biology—and traditional imaging modalities for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Bio-Optics vs. Traditional Imaging: A Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between bio-optics—the convergence of light-based technologies with biology—and traditional imaging modalities for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of bio-optics, including its core advantages of non-invasiveness, high sensitivity, and molecular specificity. The scope covers key methodological advancements such as super-resolution microscopy, photoacoustic imaging, and optical coherence tomography, alongside their applications in cancer diagnostics, neuroscience, and therapeutic monitoring. The analysis also addresses critical challenges related to standardization, data management, and clinical translation, culminating in a direct performance comparison with established techniques like MRI and CT. The synthesis aims to guide the strategic adoption of these transformative technologies in biomedical research and clinical practice.

The Principles of Bio-Optics: Unveiling the Power of Light in Biology

Bio-optics and biophotonics represent the interdisciplinary fusion of biological sciences with optical and photonic technologies. This convergence is transforming research, diagnostics, and therapy across life sciences and medicine. Biophotonics specifically denotes the combination of biology and photonics, where photonics is the science and technology of generation, manipulation, and detection of photons—the quantum units of light [1]. It can be described as the "development and application of optical techniques, particularly imaging, to the study of biological molecules, cells and tissue" [1]. The term encompasses all techniques dealing with the interaction between biological items—biomolecular, cells, tissues, organisms, and biomaterials—and photons, including their emission, detection, absorption, reflection, modification, and creation [1]. The field leverages the unique properties of light to analyze and manipulate biological materials, thereby offering new opportunities for precision measurements in fundamental and applied research, medical diagnostics, and treatment [2].

A key differentiation exists between applications that use light primarily to transfer energy, such as therapy and surgery, and those that use light to excite matter and transfer information back to the operator, such as diagnostics. The term biophotonics most frequently refers to the latter [1]. The field is recognized as a key technology of the 21st century, playing a crucial role in addressing significant societal challenges and driving advancements in life sciences, communication, and production [2]. The primary advantages of using light in biophotonics include its capability for non-contact measurement, which preserves the integrity of living cells; high speed providing real-time data; exceptional sensitivity down to single molecules; and excellent time resolution for observing dynamic biological processes across a wide range of temporal scales [2].

Core Technologies and Methodologies

The field of biophotonics can be divided into three main technological areas: bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic-based therapies. These areas often work in parallel, offering synergistic potential [2].

Key Biophotonic Imaging and Sensing Technologies

Table 1: Core Biophotonic Imaging and Sensing Technologies

| Technology | Core Principle | Primary Applications | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | Interferometry to measure backscattered light [2] | Ophthalmology, real-time 3D tissue imaging [1] [2] | High imaging speed; detailed tissue architecture [2] |

| Multi-Photon Microscopy | Simultaneous absorption of two/three photons for precise localization of fluorescence [2] | Deep tissue imaging with high spatial resolution [2] | Superior penetration depth and optical resolution [2] |

| Coherent Raman Scattering (CARS/SRS) | Nonlinear optical phenomena enhancing weak Raman signals [2] | Molecular-specific tissue imaging without autofluorescence [2] | High molecular selectivity and imaging speed [2] |

| Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI) | Combination of laser-induced ultrasound waves [2] | Deep tissue and vascular imaging [1] [2] | Superior deep tissue imaging of hemoglobin/oxygen saturation [1] |

| Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) | Measuring fluorescence decay times of endogenous fluorophores [2] | Tumor specificity, reducing non-specific signals [3] [2] | Provides biological insights beyond conventional fluorescence [3] |

| Optical Tweezers | Using light's momentum to exert forces on microscopic particles [1] | Manipulating atoms, DNA, bacteria, viruses, and nanoparticles [1] | Non-contact organizing, sorting, and tracking of cells [1] |

Photonic Therapeutic Modalities

Table 2: Core Photonic-Based Therapeutic Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism of Action | Applications | Benefits and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photodynamic Therapy (PT) | Uses photosensitizing chemicals and oxygen to induce a cellular reaction to light [1] | Killing cancer cells, treating acne, reducing scarring, antimicrobial [1] | Minimal long-term side effects; limited to surfaces/organs exposed to light [1] |

| Photothermal Therapy | Uses nanoparticles to convert light (700-1000 nm) into heat, destroying surrounding cells [1] | Treating deep-seated cancers [1] | Can target deep tissues; few long-term side effects [1] |

| Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) | Applying low-power lasers for tissue repair [1] | Reducing inflammation, chronic joint pain, potential for brain injuries [1] | Non-invasive; efficacy is sometimes controversial [1] |

| Laser Micro-Scalpel | Combining fluorescence microscopy with a femtosecond laser to excise single cells [1] | Delicate surgeries (e.g., eyes, vocal cords) [1] | Removes diseased cells without disturbing healthy surrounding cells [1] |

Biophotonics vs. Traditional Imaging Techniques

Biophotonic techniques offer distinct advantages over traditional medical imaging modalities, particularly in terms of resolution, molecular specificity, and the absence of ionizing radiation.

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Modalities

Table 3: Biophotonic Techniques vs. Traditional Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Technique | Physical Principle | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Photon Microscopy [2] | Non-linear absorption of NIR photons | Sub-micrometer | Up to ~1 mm in tissue | High resolution deep-tissue imaging, molecular specificity | Limited penetration compared to MRI/CT |

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) [2] | Low-coherence interferometry | 1-10 µm | 1-2 mm in tissue | Real-time, high-speed cellular-level resolution | Limited to superficial tissues |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) [4] | Magnetic fields and radio waves | 10-100 µm (clinical) | Whole body | Excellent soft-tissue contrast, no ionizing radiation | Long scan times, high cost, incompatible with metal implants |

| Computed Tomography (CT) [4] | X-ray absorption | 50-200 µm (clinical) | Whole body | Rapid imaging, excellent for bones and lungs | Uses ionizing radiation, poor soft-tissue contrast |

| Ultrasound (US) [4] | Reflection of sound waves | 50-500 µm | Organ-specific | Real-time imaging, no radiation, portable | Operator-dependent, limited penetration in obese patients |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) [4] | Detection of gamma rays from radiopharmaceuticals | 1-2 mm (clinical) | Whole body | High sensitivity to metabolic activity | Poor spatial resolution, uses ionizing radiation |

A paradigm shift enabled by biophotonics is the move from static anatomical assessment to dynamic, functional, and molecular imaging. Techniques like hyperspectral imaging and FLIM provide molecular contrast by visualizing native electronic chromophores such as hemoglobin, NADP(H), and flavins [2]. This allows for the unraveling of disease mechanisms, enabling prevention, early diagnosis, and targeted or personalized treatment [2]. Furthermore, biophotonic techniques often provide label-free diagnostics, exploiting intrinsic optical properties of tissues without the need for exogenous dyes, which is a significant advantage for in vivo applications [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocols in Biophotonics

Protocol: Fluorescence-Guided Surgery with Nanobodies and FLIM

This protocol leverages the rapid pharmacokinetics of Nanobodies and the analytical power of Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging for precise tumor delineation [3].

Objective: To intraoperatively distinguish tumor margins from healthy tissue using targeted Nanobody agents and FLIM.

Materials:

- Targeted Nanobody: Fluorescently labeled single-domain antibody fragments for rapid, specific tumor targeting [3].

- FLIM-Capable Imaging System: A surgical microscope or endoscope equipped with time-resolved fluorescence detection capabilities [3].

- Excitation Laser: Pulsed laser source tuned to the fluorophore's excitation wavelength.

- Control Tracer: A non-specific fluorescent tracer for comparison.

Procedure:

- Tracer Administration: Systemically administer the fluorescently labeled Nanobody to the subject prior to or during surgery.

- Waiting Period: Allow a circulation time for the Nanobody to accumulate in the target tissue and clear from the bloodstream (typically rapid due to small size).

- Intraoperative Imaging:

- Excite the surgical field with the pulsed laser source.

- Acquire fluorescence intensity images using a standard camera to identify general fluorescent regions.

- FLIM Data Acquisition:

- For regions of interest identified in step 3, acquire time-resolved fluorescence data.

- Measure the fluorescence decay curve for each pixel in the image.

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the decay curves to extract the fluorescence lifetime (τ) at every pixel.

- Generate a false-color FLIM map where color represents the lifetime value.

- Tissue Discrimination:

- Correlate the lifetime values with tissue type. Specific molecular environments in tumor versus healthy tissue will result in distinct lifetime signatures, independent of tracer concentration.

- Use this FLIM map to guide the complete resection of tumor tissue while preserving healthy tissue.

Workflow Diagram: Nanobody FLIM for Surgical Guidance

Protocol: Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) Microscopy for Label-Free Histology

This protocol uses the nonlinear optical phenomenon of SRS to generate virtual histology images without tissue staining or processing [2].

Objective: To achieve label-free, molecular-specific imaging of fresh or processed tissue sections with high chemical contrast.

Materials:

- SRS Microscope: A system featuring two synchronized pulsed lasers (pump and Stokes) focused onto the sample.

- Photodetector: A high-sensitivity detector for measuring the intensity modulation of one of the beams.

- Lock-in Amplifier: To extract the weak SRS signal from the background.

- Tissue Sample: Fresh, frozen, or fixed tissue section (label-free).

Procedure:

- Laser Setup:

- Tune the frequency difference (ωpump - ωStokes) to match a specific molecular vibrational frequency (e.g., CH₂ stretch at ~2845 cm⁻¹ for lipids).

- Sample Preparation:

- Mount the tissue section on a standard microscope slide. No staining, dehydration, or coverslipping is strictly required.

- Beam Modulation and Overlap:

- Intensively overlap the pump and Stokes beams at the sample.

- Modulate the intensity of one beam (e.g., the Stokes beam) at a high frequency (MHz).

- Signal Detection:

- Detect the pump beam after it passes through the sample.

- The SRS effect will cause a slight intensity change of the pump beam at the modulation frequency.

- Use the lock-in amplifier to detect this minute intensity change, which is proportional to the concentration of the target molecule.

- Image Generation:

- Raster-scan the beams across the sample.

- Record the lock-in amplifier output at each pixel to construct the SRS image.

- Switch the laser frequencies to target different chemical bonds (e.g., from lipids to proteins) for multi-color chemical imaging.

Workflow Diagram: SRS Microscopy for Label-Free Imaging

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in biophotonics relies on a suite of specialized reagents and optical components.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biophotonics

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., GFP, mCherry) [1] [5] | Genetically encodable, biocompatible gain media or biomarkers. | Biolasers [1], intracellular biosensing and tracking. |

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) [2] [6] | FDA-approved near-infrared fluorescent dye. | Fluorescence-guided surgery, photoacoustic imaging, assessing blood flow [6]. |

| Nanobodies [3] | Small, single-domain antibody fragments for rapid targeting. | Tumor-specific imaging agents in fluorescence-guided surgery [3]. |

| Noble Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Gold Nanorods) [1] | Strong light absorbers and scatterers, convertible to heat. | Contrast agents for imaging, mediators for photothermal therapy [1]. |

| Biocompatible Gain Media [5] | Natural dyes (e.g., riboflavin) or proteins that amplify light. | Forming the active laser medium within biological environments (biolasers) [5]. |

| Femtosecond Pulsed Lasers [1] [2] | High-intensity, ultrashort pulsed light sources. | Pump source for multi-photon microscopy and laser micro-scalpels [1] [2]. |

| Optical Fibers [1] [7] | Flexible waveguides for light delivery and collection. | Endoscopic probes, light delivery deep within tissues for sensing or therapy [1]. |

| Spectrometers [7] | Instruments for measuring wavelength and intensity of light. | Analysis of fluorescence and absorption spectra from samples [7]. |

Future Directions and Enabling Technologies

The future of biophotonics is being shaped by several key enabling technologies. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are playing an increasingly transformative role by enhancing data analysis, interpretation, and optimization of complex imaging and sensing [3] [2]. AI is being leveraged for tasks ranging from image reconstruction and interpretation to optical design itself [3]. However, the "black box" nature of some complex AI models poses challenges for transparency and explainability in medical decision-making, an issue being addressed by emerging regulations like the European Union's AI Act [8].

Novel Materials, particularly biophotonic probes derived from biological entities like viruses and cells, are being developed to create seamless interfaces between optical and biological worlds [5]. These probes offer high biocompatibility, biodegradability, and the unique ability to serve simultaneously as optical devices and diagnostic specimens [5]. Furthermore, Quantum Biophotonics is an emerging frontier, with research demonstrating optically addressable protein-based spin qubits in fluorescent proteins, which have coherence times rivaling NV centers in nanodiamonds but are genetically encodable and roughly ten times smaller [3]. The global biophotonics market, valued at $62.6 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $113.1 billion by 2030, reflects the vigorous commercial and technological momentum of this field [9].

The field of bio-optics represents the innovative convergence of biology, medicine, and photonics, employing light to analyze and manipulate biological materials [2]. This interdisciplinary fusion has transformed research, diagnostics, and therapy across various domains, offering significant advantages over traditional imaging techniques such as X-ray computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [2] [10]. Unlike ionizing radiation-based methods, bio-optical techniques utilize the interactions between light and biological matter—specifically absorption, emission, scattering, and reflection—to generate contrast and provide information about biological systems non-invasively and with high sensitivity [2] [11].

The fundamental principle underlying bio-optics is that when light encounters biological tissue, it undergoes various physical interactions that can be measured and interpreted to reveal structural, functional, and molecular information [2] [11]. These interactions form the basis for a wide array of bio-optical technologies that enable visualization of biological processes across multiple spatial scales, from single molecules to entire organs [2]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core interaction phenomena, framed within the context of a broader thesis comparing bio-optics with traditional imaging techniques for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles of Light-Tissue Interactions

Photon Transport in Biological Tissue

When light propagates through biological tissues, it undergoes a series of photophysical interactions including absorption, scattering, and reflection [12] [11]. The trajectory of individual photons is determined by the optical properties of the tissue, which vary depending on molecular composition, structural organization, and physiological state [11]. These interactions are not mutually exclusive; rather, they occur simultaneously, with their relative predominance depending on the optical properties of the tissue at specific wavelengths [2].

The key advantage of utilizing these light-tissue interactions for imaging lies in their ability to provide non-contact measurement, enabling observation of living cells without compromising their integrity [2]. Additionally, optical measurements offer exceptional speed for real-time data acquisition, ultrasensitive detection capabilities down to single molecules, and excellent time resolution for observing dynamic biological processes across various temporal scales [2].

Core Interaction Phenomena

The four primary phenomena governing light-tissue interactions are:

- Absorption: Process where light energy is transferred to molecular chromophores, causing electronic transitions [2]

- Emission: Process where excited molecules return to ground state, releasing energy as photons [11]

- Scattering: Redirection of light caused by interactions with microscopic variations in refractive index [2] [12]

- Reflection: Return of light from tissue interfaces due to differences in refractive indices [2]

These interaction phenomena are distinguished by their capacity to elucidate a vast array of morphological and molecular intricacies across a spectrum of size scales, encompassing macroscopic, microscopic, and nanoscopic resolutions [2].

Figure 1: Fundamental light-tissue interactions and their applications in bio-optical imaging techniques.

Quantitative Analysis of Interaction Phenomena

Performance Metrics Across Modalities

The effectiveness of bio-optical imaging techniques depends critically on how they leverage the core interaction phenomena. Different modalities optimize for specific interactions to achieve desired performance characteristics including penetration depth, resolution, and molecular specificity.

Table 1: Performance comparison of bio-optical imaging modalities based on core interaction phenomena

| Imaging Modality | Primary Interaction | Penetration Depth | Spatial Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | Scattering, Reflection | 1-3 mm [2] | 1-15 μm [2] | Ophthalmology, tissue morphology [2] [13] |

| Multi-photon Microscopy | Absorption, Emission | ~1 mm [2] | <1 μm [2] | Deep tissue cellular imaging [2] |

| Photoacoustic Imaging | Absorption | Several cm [10] | 10-200 μm [10] | Vascular imaging, oxygen saturation [10] |

| Diffuse Optical Tomography | Scattering | Several cm [11] | 5-10 mm [11] | Breast cancer imaging, brain functional imaging [11] |

| NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging | Emission, Absorption | Millimeters to centimeters [12] | High spatiotemporal resolution [12] | Tumor imaging, vascular imaging, surgical navigation [12] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Scattering | Surface/subsurface [2] | Molecular fingerprinting [2] [14] | Biochemical analysis, disease biomarkers [2] [14] |

Wavelength-Dependent Interactions

The nature and efficiency of light-tissue interactions vary significantly with wavelength, creating distinct optical windows for biomedical applications.

Table 2: Wavelength-dependent characteristics of light-tissue interactions

| Spectral Region | Wavelength Range | Primary Interactions | Tissue Effects | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultraviolet (UV) | 200-400 nm | Strong absorption, scattering | Photodamage, limited penetration | Surface fluorescence, microscopy [11] |

| Visible | 400-700 nm | Moderate absorption and scattering | Good contrast, moderate penetration | Color imaging, oximetry [12] [11] |

| Near-infrared I (NIR-I) | 700-1000 nm | Reduced scattering, low absorption | Deep penetration | Optical coherence tomography, diffuse tomography [12] |

| Near-infrared II (NIR-II) | 1000-1700 nm | Minimal scattering and absorption | Maximum penetration | Deep tissue imaging, biosensing [12] |

Experimental Methodologies

Protocol 1: NIR-II Fluorescence Bioimaging

Principle: Utilizing fluorophores emitting in the second near-infrared window (1000-1700 nm) where tissue absorption and scattering coefficients are significantly reduced, enabling enhanced penetration depth and spatiotemporal resolution [12].

Materials:

- NIR-II fluorophore (quantum dots, single-walled carbon nanotubes, rare-earth-doped nanoparticles, conjugated polymers, or organic dyes) [12]

- NIR-compatible excitation source (tunable laser system)

- InGaAs or other NIR-II sensitive detector

- Animal model or tissue sample

- Anesthesia system (for in vivo studies)

- Data acquisition and processing software

Procedure:

- Administer NIR-II fluorophore via intravenous injection (for in vivo) or add to media (for in vitro)

- Allow appropriate circulation/uptake time (typically 1-24 hours depending on application)

- Anesthetize animal if performing in vivo imaging

- Set excitation wavelength according to fluorophore absorption maximum (typically 808 nm for many NIR-II probes)

- Acquire time-series images using NIR-II detector

- Process images to remove background autofluorescence

- Quantify signal intensity in regions of interest

- Perform biodistribution analysis if required

Key Parameters:

- Excitation power density: <100 mW/cm² for in vivo to prevent tissue damage

- Acquisition frame rate: Adjust based on phenomenon of interest (seconds to minutes)

- Spectral filters: Optimized for specific emission ranges within NIR-II window

- Image analysis: Include flat-field correction, background subtraction, and spectral unmixing if multiple probes used

Protocol 2: Photoacoustic Imaging

Principle: Combines optical excitation with acoustic detection based on the photoacoustic effect, where chromophores absorb pulsed light, undergo thermoelastic expansion, and generate ultrasound waves that reflect optical absorption properties [10].

Materials:

- Pulsed laser source (Nd:YAG, OPO, or diode laser) with nanosecond pulse width

- Ultrasound transducer (single-element for microscopy, array for tomography)

- Data acquisition system with high-speed digitizer

- Scanning system (for microscopy implementations)

- Image reconstruction software

- Animal model or tissue sample

Procedure:

- Position sample or animal in imaging chamber

- Adjust laser parameters: wavelength (according to chromophore absorption), pulse energy, repetition rate

- Align ultrasound transducer with respect to illumination spot

- Acquire photoacoustic signals following each laser pulse

- Scan transducer or sample if using single-element detection

- Reconstruct images using appropriate algorithm (delay-and-sum, time-reversal, or model-based)

- Process images to extract quantitative parameters (oxygen saturation, chromophore concentration)

Key Parameters:

- Laser wavelength: Selected based on target chromophore (e.g., 532 nm for hemoglobin, 750-900 nm for contrast agents)

- Pulse duration: Typically 1-100 ns to satisfy stress confinement

- Ultrasound transducer frequency: Trade-off between resolution and depth (1-100 MHz)

- Reconstruction algorithm: Chosen based on system geometry and signal-to-noise requirements

Protocol 3: Adaptive Optics Ophthalmoscopy

Principle: Corrects ocular aberrations in real-time using wavefront sensing and deformable mirrors, enabling diffraction-limited imaging of retinal structures at cellular resolution [13].

Materials:

- Adaptive optics system with wavefront sensor (Shack-Hartmann)

- Deformable mirror

- Multi-modal imaging system (confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, fluorescence, OCT)

- Light sources for imaging and wavefront sensing

- Computer for real-time control and image acquisition

- Human subject or animal model

Procedure:

- Align subject's eye with optical system

- Measure wavefront aberrations using wavefront sensor

- Compute correction signals using control algorithm

- Apply correction via deformable mirror

- Verify correction quality by measuring residual aberrations

- Acquire high-resolution retinal images using various contrast mechanisms (reflectance, fluorescence, multiphoton)

- Process images to correct for residual distortions and enhance signal-to-noise ratio

Key Parameters:

- Wavefront sensor sampling: Sufficient to capture higher-order aberrations

- Correction rate: Typically 10-100 Hz to track dynamic aberrations

- Imaging wavelength: Selected based on target structures (e.g., 790 nm for photoreceptors, 550 nm for blood vessels)

- Power levels: Maintained within safe retinal exposure limits

Figure 2: Generalized workflow for bio-optical imaging experiments, highlighting key stages from sample preparation to quantitative analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of bio-optical imaging requires specialized reagents and materials designed to enhance, quantify, or modulate light-tissue interactions.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for bio-optical investigations

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Fluorophores | Organic dyes, quantum dots, single-walled carbon nanotubes, rare-earth nanoparticles [12] | Emission signal generation in 1000-1700 nm range for deep tissue imaging | Tumor imaging, vascular mapping, surgical navigation [12] |

| Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins | Green/red fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP) and their variants [11] | Labeling specific proteins or cells for visualization in live specimens | Protein localization, cell tracking, gene expression studies [11] |

| Target-Specific Molecular Probes | Antibodies, peptides, or small molecules conjugated to fluorophores [11] | Binding to specific biomarkers for molecular imaging | Cancer biomarker detection, inflammation imaging [11] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Spherical, rod-shaped, or nanostructured gold particles [11] | Enhancing optical contrast through scattering and absorption | Photoacoustic imaging, biosensing, thermal therapy [11] |

| Environmental-Responsive Probes | Fluorophores with sensing moieties for pH, ions, or metabolites [11] | Reporting on subcellular microenvironment changes | Metabolic activity monitoring, organelle-specific sensing [11] |

| Adaptive Optics Components | Wavefront sensors, deformable mirrors, control algorithms [13] | Correcting optical aberrations in real-time | High-resolution retinal imaging, deep tissue microscopy [13] |

Comparative Analysis: Bio-Optics vs. Traditional Imaging

Technical Advantages of Bio-Optical Methods

Bio-optical imaging techniques offer several distinct advantages over traditional imaging modalities:

Non-ionizing Nature: Unlike X-ray CT and PET, bio-optical methods utilize non-ionizing radiation, enabling repeated imaging sessions without cumulative radiation exposure [11] [10]. This is particularly advantageous for longitudinal studies, pediatric applications, and monitoring treatment response.

Molecular Sensitivity: Optical techniques can detect specific molecular targets through endogenous contrast or targeted agents with high specificity [2] [11]. Traditional anatomical imaging modalities like CT and MRI primarily provide structural information and often require contrast agents for functional assessment.

Real-time Capabilities: The high speed of optical measurements enables real-time monitoring of dynamic biological processes [2]. This temporal resolution exceeds that of most traditional modalities, facilitating studies of physiological processes, drug delivery, and surgical guidance.

Cost-effectiveness and Accessibility: Bio-optical systems are generally more compact and affordable than MRI, CT, or PET scanners, making them more accessible for research and clinical applications [10].

Limitations and Complementary Role

Despite these advantages, bio-optical imaging faces certain limitations:

Penetration Depth: Light scattering in biological tissue fundamentally limits penetration depth to a few centimeters, whereas CT, MRI, and PET can image the entire body [12] [10]. This restricts bio-optical methods to superficial structures, small animals, or intraoperative applications.

Quantification Challenges: Light attenuation and scattering complicate quantitative measurements compared to more established modalities like CT, where attenuation coefficients directly relate to material density.

Clinical Translation Barriers: While numerous bio-optical techniques have proven invaluable in research, regulatory approval and clinical adoption have been slower than for traditional modalities, particularly for novel contrast agents [12] [14].

The future of biomedical imaging lies not in replacement but in complementarity, with hybrid approaches combining the strengths of multiple modalities. For instance, photoacoustic imaging merges optical contrast with ultrasound resolution, effectively addressing the depth limitation of pure optical methods [10].

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Integration with Artificial Intelligence

Machine learning and artificial intelligence are transforming bio-optical imaging through enhanced image reconstruction, interpretation, and optical design [2] [3]. AI algorithms can extract subtle patterns from optical data that are imperceptible to human observers, enabling earlier disease detection and more precise quantification. The integration of AI is particularly valuable for resolving the inverse problem in diffuse optical tomography and for analyzing complex data from hyperspectral imaging techniques [2].

Novel Materials and Contrast Mechanisms

The development of advanced contrast agents represents a vibrant research frontier. Second near-infrared window (NIR-II) fluorophores continue to evolve with improvements in quantum yield, biocompatibility, and targeting specificity [12]. Stimuli-responsive probes that alter their optical properties in response to specific biomarkers enable sensing of physiological parameters with high spatiotemporal resolution [11]. Additionally, nanomaterials with tailored optical properties are expanding the capabilities of bio-optical techniques for both diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Clinical Translation and Commercial Outlook

The biophotonics market is projected to grow significantly, with estimates exceeding $100 billion by 2032, reflecting increasing clinical adoption and technological advancement [15]. Key growth areas include point-of-care diagnostics, minimally invasive surgical guidance, and therapeutic monitoring. Optical coherence tomography has already established strong clinical utility in ophthalmology, while other techniques like photoacoustic imaging and diffuse optical tomography are progressing toward broader clinical implementation [14] [10].

The core interaction phenomena of absorption, emission, scattering, and reflection form the physical foundation for bio-optical imaging techniques that are revolutionizing biomedical research and clinical practice. These light-tissue interactions enable non-invasive visualization of biological structures and processes across multiple spatial and temporal scales, with advantages in molecular sensitivity, safety, and cost-effectiveness compared to traditional imaging modalities. While penetration depth limitations present challenges for certain applications, ongoing advancements in instrumentation, contrast agent design, and computational methods continue to expand the capabilities and applications of bio-optical imaging. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these fundamental principles and their implementation is essential for leveraging the full potential of bio-optics in scientific discovery and translational medicine.

Bio-optics, the interdisciplinary fusion of light-based technologies with biology and medicine, is fundamentally transforming biomedical research and clinical diagnostics [2]. This technical guide examines the core advantages that establish bio-optical methods as superior to traditional imaging and analytical techniques across numerous applications. The convergence of advanced photonic technologies with biology has enabled a new generation of tools that operate without damaging samples, deliver results in real-time, and detect individual molecules with extraordinary precision [16] [2]. These capabilities are reshaping experimental approaches in basic research and accelerating translational applications in drug development, clinical diagnostics, and therapeutic monitoring [17]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these advantages, supported by current experimental data and methodologies, framed within the broader context of bio-optics versus traditional imaging techniques research.

Core Technical Advantages: A Comparative Analysis

Non-Invasiveness: Preserving Native Biological States

Non-invasive measurement stands as a foundational advantage of bio-optical techniques, enabling observation of living cells and biological processes without compromising sample integrity or inducing toxic effects [2]. Unlike conventional methods that often require fixation, staining, or physical disruption of samples, optical measurements facilitate the longitudinal study of dynamic processes in their native states.

- Mechanism of Action: Bio-optical techniques leverage various forms of light-matter interaction—including absorption, emission, reflection, and scattering—to extract biological information without physical contact or destructive sampling [2]. This non-contact approach preserves the viability of cells and tissues, enabling repeated observations over time.

- Comparative Advantage: Traditional histological methods require tissue fixation, sectioning, and staining, processes that permanently alter samples and prevent longitudinal studies. In contrast, techniques like optical coherence tomography (OCT) and adaptive optics ophthalmoscopy provide detailed structural information while maintaining full sample viability [13].

- Experimental Evidence: Research on retinal organoids and explants demonstrates how fully automated OCT systems enable non-invasive, high-throughput 3D imaging and quantification of tissue architecture for drug discovery applications, eliminating the need for destructive histology methods [13]. Similarly, adaptive optics technologies correct optical imperfections in the eye to visualize individual retinal cells, including photoreceptors, microglia, and blood vessels, in living subjects without biopsy [13].

Speed and Real-Time Capability: Instantaneous Biological Insights

The speed and instant information delivery capability of optical measurements represents a transformative advantage, providing rapid, real-time data that significantly reduces the time required for data interpretation and diagnosis [2].

- Technical Foundation: The inherent speed of light enables temporal resolution ranging from hours for slow biological processes to ultrafast reactions, capturing dynamic molecular and cellular events inaccessible to conventional methods [2].

- Implementation Examples: Optical coherence tomography (OCT) stands as one of the fastest methods in terms of volume elements (voxels) imaged per second, enabling real-time 3D imaging of dynamic processes that has established its clinical utility in ophthalmology [2]. Advanced microfluidic platforms integrated with optical detection achieve response times as low as seven milliseconds with 100% success rates in automated object detection [13].

- Impact on Research and Diagnostics: This temporal resolution enables researchers to monitor cellular processes, molecular interactions, and therapeutic responses as they occur, transforming our understanding of biological dynamics and accelerating diagnostic procedures [18]. For drug development professionals, this capability provides real-time insights into compound effects during screening campaigns, dramatically reducing development timelines.

Single-Molecule Sensitivity: Ultimate Detection Limits

The ability to achieve single-molecule sensitivity represents perhaps the most significant technical advancement enabled by bio-optical methods, revealing heterogeneities and transient states invisible to conventional ensemble measurements [19].

- Fundamental Principles: Label-free single-molecule detection techniques exploit intrinsic molecular properties—particularly scattering and refractive index changes—to achieve detection at the ultimate sensitivity limit [19]. For biomolecules in aqueous environments, the inherently low refractive index contrast creates weak scattering signals that modern photonic sensors overcome through interference, plasmonic enhancement, and optical resonance phenomena [19].

- Quantitative Performance: Next-generation photonic sensors now enable detection at attomolar (10⁻¹⁸ M) and even zeptomolar (10⁻²¹ M) levels, surpassing the sensitivity limits of conventional fluorescence-based methods [16]. Techniques like interferometric scattering microscopy (iSCAT) can detect single proteins in the tens of kilodalton range, functioning as an optical analog of mass spectrometry for precise mass profiling and real-time tracking of molecular transport [19].

- Methodological Advancements: Plasmonic sensors based on individual metal nanoparticles provide confined modes with significantly smaller probing volumes than traditional surface plasmon resonance (SPR), enabling true single-molecule resolution for biomolecular interaction analysis [19]. Nanofluidic scattering microscopy (NSM) employs nanochannels to container freely diffusing molecules, enabling stable signal detection throughout the imaging process for both molecular mass and diffusivity measurements [19].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Bio-Optical Techniques Enabling Single-Molecule Sensitivity

| Technique | Detection Principle | Sensitivity Limit | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iSCAT | Interference between scattered and reference light | Single proteins (~10s kDa) [19] | Millisecond to second [19] | Mass profiling, molecular transport, interaction studies [19] |

| Plasmonic Nanosensors | Refractometric detection via resonance shift | Single biomolecule binding events [19] | Real-time monitoring [19] | Biomolecular interaction analysis, affinity determination [19] |

| Nanofluidic Scattering | Interference with channel-scattered reference | Single proteins (comparable to iSCAT) [19] | Stable during diffusion [19] | Mass and diffusivity measurements [19] |

| WGM Resonators | Resonance shift from binding-induced refractive index change | Attomolar to zeptomolar [16] | Real-time [16] | Cancer diagnostics, viral identification, pollutant sensing [16] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for High-Sensitivity Detection

Protocol: Interferometric Scattering (iSCAT) for Single-Protein Detection

Principle: iSCAT detects biomolecules through interference between light scattered by the analyte and a reference wave reflected from a substrate interface [19]. The interference term in the detected intensity (2|Er||Es|cosϕ) becomes the dominant signal for subwavelength particles, enabling detection of single proteins with masses in the kilodalton range [19].

Experimental Workflow:

- Substrate Preparation: Use coverslips with controlled refractive index and thickness, typically cleaned and functionalized for specific binding applications.

- Optical Configuration: Employ epi-illumination with laser sources (typically 405-660 nm), high-numerical-aperture objectives (NA 1.2-1.5), and fast scientific CMOS or EMCCD cameras [19].

- Reference Wave Management: Optimize the reference wave intensity relative to the scattering signal to maximize contrast while minimizing background fluctuations.

- Sample Application: Introduce protein solutions at appropriate concentrations (pM-nM range) to enable single-molecule binding events to the functionalized surface.

- Image Acquisition: Record video-rate sequences (50-1000 frames/s) to capture binding and diffusion events.

- Data Analysis: Apply background subtraction algorithms and analyze interference contrast, which scales linearly with protein mass, enabling quantitative mass determination at the single-molecule level [19].

Critical Considerations: Detection sensitivity depends strongly on phase stability, restricting optimal detection to surface-bound or near-surface molecules. Rapid phase fluctuations from axial diffusion of molecules in solution can average out the signal [19].

Protocol: Plasmonic Nanoparticle Sensing for Biomolecular Interactions

Principle: Single metal nanoparticles support localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs) that shift in response to local refractive index changes caused by biomolecules binding to their surfaces [19].

Experimental Workflow:

- Nanoparticle Fabrication: Synthesize or commercially source monodisperse gold or silver nanoparticles (typically 20-100 nm diameter) and immobilize on functionalized substrates.

- Surface Functionalization: Modify nanoparticle surfaces with capture molecules (antibodies, DNA oligonucleotides, etc.) specific to the target analyte.

- Optical Setup: Implement dark-field microscopy, photothermal imaging, or total internal reflection scattering to monitor individual nanoparticles with high signal-to-noise ratio.

- Spectral Monitoring: Track resonance wavelength shifts of single nanoparticles in real-time using spectrophotometric detection or scattering-based approaches.

- Binding Kinetics: Introduce analyte solutions and monitor resonance shifts versus time to extract binding kinetics and affinity constants.

- Data Analysis: Fit binding curves to appropriate kinetic models (Langmuir, etc.) to determine association and dissociation rate constants [19].

Critical Considerations: The small surface area of individual nanoparticles (a 50 nm particle accommodates ~100 proteins) enables true single-molecule detection but requires careful statistical analysis of multiple nanoparticles to account for heterogeneity [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Bio-Optical Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Coverslips | Provides substrate for biomolecule immobilization with controlled refractive properties | iSCAT, TIRF, single-molecule tracking [19] |

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles | Enhances optical signals via localized surface plasmon resonance | Single-particle sensing, enhanced spectroscopy [19] |

| DNA Nanostructures | Precisely positions molecules and functions on nanoscale | Modular single-molecule sensors, nanodevice assembly [20] |

| Fluorescent Proteins (GFP, RFP) | Genetically encoded labels for specific protein visualization | Live-cell imaging, protein localization and dynamics [14] |

| Raman Tags | Provides distinct vibrational signatures for multiplexed detection | Raman spectroscopy, chemical imaging of cellular components [14] |

| Microfluidic Chips | Enables precise environmental control and high-throughput screening | Organoid imaging, single-cell analysis, drug screening [18] |

| Advanced Fluorophores | Bright, photostable labels for prolonged single-molecule tracking | Super-resolution microscopy, single-molecule fluorescence [20] |

Technical Challenges and Emerging Solutions

Despite these significant advantages, bio-optical methods face several technical challenges that active research is addressing:

- Noise Suppression: Weak single-molecule signals require sophisticated noise reduction strategies. Solutions include computational approaches (machine learning denoising), lock-in detection methods, and plasmonic enhancement to boost signal-to-noise ratios [16] [18].

- Fabrication Complexity: Nanophotonic structures enabling single-molecule detection often involve complex fabrication. Emerging solutions include DNA nanotechnology for self-assembled structures [20] and improved nanofabrication protocols [16].

- Bio-Compatibility: Maintaining biological function while achieving sufficient optical contrast remains challenging. Label-free methods address this by eliminating exogenous probes, while advanced functionalization strategies improve biocompatibility of interfaces [16] [19].

- Data Interpretation: The complexity of bio-optical data requires advanced analysis tools. Machine learning and artificial intelligence are increasingly deployed for image analysis, feature extraction, and data interpretation [2] [18].

Bio-optical technologies have established a new paradigm for biological investigation and clinical diagnostics through their fundamental advantages in non-invasiveness, speed, and single-molecule sensitivity. These capabilities are driving transformative applications across biomedical research, drug development, and clinical practice. The continued advancement of photonic sensors, combined with emerging enhancements from artificial intelligence, hybrid sensor architectures, and miniaturization for point-of-care applications, promises to further accelerate the adoption of these technologies [16] [2]. As these methodologies mature, they are poised to redefine the standards for biological measurement and therapeutic monitoring, enabling unprecedented insights into cellular and molecular processes that underlie health and disease. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and leveraging these advantages is essential for driving the next generation of biomedical innovations.

The field of biomedical science is experiencing a fundamental transformation driven by the convergence of optical technologies, nanomaterials science, and artificial intelligence. This paradigm shift from traditional imaging techniques to integrated bio-optics platforms addresses critical limitations in conventional modalities like MRI, CT, and PET, which often involve ionizing radiation, limited spatial-temporal resolution, complex infrastructure requirements, and high costs [21]. Bio-optical approaches leverage the unique properties of light-matter interactions at micro and nanoscales to enable non-invasive, high-resolution, and multi-parametric assessment of biological systems with unprecedented sensitivity and specificity. These core technology pillars—bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic therapies—are converging toward unified platforms that provide comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities, ultimately advancing personalized medicine through enhanced molecular-level precision, real-time monitoring, and minimally invasive interventions.

Core Technology Pillar I: Advanced Bioimaging

Advanced bioimaging technologies represent the foundational pillar of modern bio-optics, enabling visualization of biological structures and processes across multiple scales from single molecules to entire organisms.

Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI)

Photoacoustic imaging elegantly bridges optical contrast and acoustic resolution, overcoming the traditional depth limitations of pure optical microscopy. This hybrid modality operates on the photoacoustic effect, where short laser pulses illuminate chromophores in tissue, causing rapid thermoelastic expansion and generating ultrasonic waves that convey optical absorption properties with acoustic resolution [10]. The initial pressure of the photoacoustic wave is determined by the equation: p₀ = ΓηthμaF, where Γ is the Grüneisen parameter, ηth is the photothermal conversion efficiency, μa is the optical absorption coefficient, and F is the optical fluence [10].

PAI systems employ various detection technologies categorized into ultrasonic transducers and optical sensing methods. Conventional piezoelectric transducers using materials like PVDF, PZT, and PMN-PT can be configured as single-element detectors for high-resolution microscopy (PAM) or multi-element arrays for computed tomography (PACT) [10]. Recent advancements include piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers (PMUTs) and capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducers (CMUTs) that combine MEMS technology with conventional approaches, offering improved performance with customizable sizes and shapes [10].

Diagram 1: Photoacoustic imaging workflow. The process begins with pulsed laser excitation, leading to ultrasound generation via the photoacoustic effect, followed by detection and computational reconstruction.

Near-Infrared-II (NIR-II) Imaging

The discovery of the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm) represents a breakthrough in deep-tissue optical imaging. NIR-II technology provides unprecedented tissue penetration depth, low photon scattering, and negligible autofluorescence compared to traditional visible-light and NIR-I fluorescence imaging [21]. This capability dramatically improves sensitivity and specificity for biological sensing and imaging applications, enabling dynamic tracking of cell distribution and fate in deep tissues and organs with high spatial-temporal resolution and improved signal-to-noise ratio [21].

NIR-II imaging employs various contrast agents including quantum dots (QDs), semiconducting polymer dots (Pdots), rare-earth-doped nanoparticles, and small-molecular organic fluorophores [21]. Key parameters for optimal performance include cellular labeling brightness, chemostability, photostability, biocompatibility, and functionalization capabilities for targeted imaging.

Hybrid Imaging Platforms

The integration of multiple imaging modalities creates synergistic platforms that overcome individual limitations. A groundbreaking development from UC Davis combines PET and dual-energy CT in a novel configuration called PET-enabled Dual-Energy CT [22]. This approach uses PET scan data to create a second, high-energy CT image, enabling dual-energy imaging that provides detailed tissue composition information without new hardware or additional radiation exposure [22]. This hybrid technique enhances cancer detection, improves bone marrow scanning, and provides new insights into cardiovascular risk assessment, potentially implementable on existing PET/CT scanners without expensive equipment upgrades [22].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Bio-optical Imaging Modalities Versus Traditional Techniques

| Imaging Modality | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Imaging | 10-50 μm | 5-10 mm | Low autofluorescence, high spatio-temporal resolution | Limited clinical translation of contrast agents |

| Photoacoustic Imaging | 20-200 μm | 2-5 cm | Combines optical contrast with ultrasound resolution | Limited by optical absorption properties |

| PET-enabled DECT | 0.5-1 mm | Whole body | Provides metabolic and compositional data | Requires radiotracers, higher cost |

| MRI | 0.1-1 mm | Whole body | Excellent soft tissue contrast | Low temporal resolution, high cost |

| CT | 0.2-0.5 mm | Whole body | Fast acquisition, excellent bone imaging | Ionizing radiation, poor soft tissue contrast |

| Fluorescence (NIR-I) | 5-20 μm | 1-2 mm | High sensitivity, real-time imaging | Limited penetration, autofluorescence |

Core Technology Pillar II: Biosensing and Diagnostics

Biosensing technologies have evolved from simple analyte detection to sophisticated systems integrating nanophotonics, molecular recognition, and artificial intelligence for comprehensive diagnostic applications.

Nanophotonic Biosensing

Nanophotonics—the manipulation of light at the nanometer scale—enables control of optical fields beyond diffraction limits through phenomena like near-field coupling, photonic bandgap (PBG) effects, and localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) [23]. These capabilities allow nanostructures to confine and manipulate light with high precision, creating powerful biomedical tools for diagnosis and monitoring.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) arises when incident light couples with free electrons at a metal-dielectric interface, producing resonance exquisitely sensitive to changes in the local refractive index [23]. Modern SPR platforms integrate advanced computational modeling using Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) and Finite Element Method (FEM) simulations to optimize sensor geometry and material selection for enhanced performance [23].

Plasmonic nanoparticles, particularly gold (AuNPs) and silver (AgNPs), sustain LSPR and generate localized electromagnetic fields that amplify optical signals in their immediate vicinity [23]. These nanoparticles enable surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), plasmon-enhanced fluorescence, and photothermal imaging. Anisotropic structures like nanorods and nanostars exhibit resonances in the near-infrared region, penetrating biological tissues for deep-tissue imaging and targeted therapies [23].

Elemental Imaging and Analysis

Elemental bioimaging techniques provide crucial information about tissue composition for clinical diagnostics and research. Modern methods including laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS), laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS), X-ray fluorescence (XRF), and electron microscopy methods (SEM/TEM-EDS) enable mapping of elemental distributions in biological samples [24]. These techniques are revolutionizing areas from oncology to neurology by detecting pathogens, monitoring therapy safety, determining intracellular processes, and assessing the necessity for implant revision [24].

Critical parameters ensuring measurement quality include selectivity, detection limits, linearity, and precision, though challenges remain in standardization, calibration materials, and accuracy assessment for trace elements [24].

Integrated Diagnostic Systems

The convergence of multiple technologies creates diagnostic systems with enhanced capabilities. A prime example is a dual-mode optical imaging system developed by researchers at Saint-Étienne University Hospital and Paris-Saclay University, which combines line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT) with confocal Raman microspectroscopy [25]. This system captures high-resolution cellular-level images while simultaneously analyzing chemical composition, achieving 95% classification accuracy for basal cell carcinoma in clinical testing on over 330 skin cancer samples [25]. The integration of artificial intelligence for pattern recognition further enhances diagnostic reliability by distinguishing cancerous tissues based on their chemical signatures [25].

Diagram 2: Integrated biosensing pathway. Nanophotonic probes interact with biological samples, transducing molecular recognition events into optical signals enhanced by AI analysis.

Core Technology Pillar III: Photonic Therapies

Photonic therapies harness light-matter interactions for precise, targeted treatment modalities with minimal invasiveness and reduced side effects compared to conventional approaches.

Photothermal Therapy (PTT)

Photothermal therapy utilizes light-absorbing nanoparticles to generate localized heat under external illumination. Recent advances include size-regulated antimony nanoparticles that precisely adjust localized surface plasmon resonance to match therapeutic laser wavelengths, enhancing both photothermal and photodynamic effects [26]. These semimetallic nanomaterials demonstrate high photothermal conversion efficiencies while maintaining biocompatibility, offering promising alternatives to traditional noble metal nanoparticles [26].

Gold nanorods (AuNRs) represent another advanced platform, converting NIR (850 nm) light into thermal energy with high efficiency. Their anisotropic structure enables resonance tuning to tissue-transparent near-infrared wavelengths, facilitating deeper tissue penetration for ablation of malignant cells while sparing surrounding healthy tissue [23].

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

Photodynamic therapy combines photosensitizing agents with specific wavelength light to generate reactive oxygen species that selectively destroy target cells. The integration of nanotechnology has addressed traditional limitations in photosensitizer delivery, specificity, and efficacy. Advanced platforms include two-dimensional materials, quantum dots, and self-assembled nanostructures with tunable optical, electrical, and biochemical properties [26]. These materials act as transducers, amplifying biological recognition events into measurable signals, or as therapeutic agents delivering payloads with spatial and temporal precision [26].

Image-Guided Interventions

The combination of diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities creates theranostic platforms that enable real-time treatment monitoring and adjustment. Nanomaterials with responsiveness to multiple stimuli—pH, temperature, light, or enzymatic activity—create opportunities for systems where detection and treatment are seamlessly linked [26]. This integration is particularly valuable in oncology, where precise tumor delineation and targeted ablation significantly improve treatment outcomes while reducing collateral damage to healthy tissues.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Dual-Mode Optical Imaging for Skin Cancer Diagnosis

This protocol outlines the methodology for combining line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT) and confocal Raman microspectroscopy based on clinical validation studies [25].

Sample Preparation:

- Obtain fresh biopsy samples or perform in vivo measurements on suspected skin lesions

- Clean the area with saline solution to remove surface contaminants

- For ex vivo samples, mount in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound without chemical fixation

Instrument Setup:

- Configure LC-OCT system with superluminescent diode source (central wavelength ~830 nm)

- Align confocal Raman microspectroscopy system with 785 nm laser excitation

- Calbrate both systems using standardized reflectance phantoms and Raman standards

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire LC-OCT images of suspicious regions with field of view of ~1.2 × 0.8 mm

- Collect high-resolution depth-resolved images down to ~500 μm penetration

- Perform Raman spectral mapping on regions identified as abnormal by LC-OCT

- Collect 1,300-1,500 spectra per sample with integration times of 1-5 seconds

Data Analysis:

- Preprocess Raman spectra with smoothing, baseline correction, and vector normalization

- Apply principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction

- Train support vector machine (SVM) classifier with cross-validation

- Correlate molecular features from Raman with structural features from LC-OCT

Protocol: NIR-II Cell Tracking in Live Animals

This protocol details procedures for in vivo cell tracking using NIR-II fluorescence imaging based on established methodologies [21].

Cell Labeling:

- Culture target cells (e.g., stem cells, immune cells) in standard conditions

- Incubate with NIR-II contrast agent (e.g., rare-earth-doped nanoparticles, quantum dots) for 4-24 hours

- Remove excess label through multiple washing steps with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Verify labeling efficiency and cell viability using flow cytometry and trypan blue exclusion

Animal Preparation:

- Anesthetize animal using isoflurane or ketamine/xylazine based on institutional guidelines

- Position animal in imaging chamber with temperature maintenance at 37°C

- Administer cells via appropriate route (intravenous, intramuscular, etc.)

Imaging Acquisition:

- Set up NIR-II imaging system with 808 nm or 980 nm laser excitation

- Configure InGaAs camera with appropriate filters for NIR-II detection (1000-1700 nm)

- Acquire time-series images at predetermined intervals (e.g., 0, 6, 24, 48 hours)

- Include control animals receiving unlabeled cells for background subtraction

Image Processing:

- Apply flat-field correction to account for uneven illumination

- Subtract autofluorescence background using control images

- Quantify signal intensity in regions of interest (ROIs)

- Reconstruct 3D distributions using tomographic approaches when applicable

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Bio-optics Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Functions | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles | Gold nanorods, silver nanostars, antimony nanoparticles | Photothermal conversion, signal enhancement for SERS | Size and shape dictate resonance wavelength; surface chemistry affects targeting |

| NIR-II Contrast Agents | Rare-earth-doped nanoparticles, single-walled carbon nanotubes, quantum dots | Deep-tissue fluorescence imaging | Emission tails beyond 1000 nm reduce scattering; functionalization enables specific targeting |

| Photoacoustic Contrast Agents | Indocyanine green derivatives, methylene blue, gold nanocages | Enhanced optical absorption for PA signal generation | Biocompatibility and clearance profiles crucial for clinical translation |

| Gene Editing Components | CRISPR-Cas systems, guide RNA, repair templates | Precision genetic modification | Can be integrated with optical readouts for real-time monitoring of editing efficiency |

| Surface Chemistry Reagents | PEG linkers, thiol compounds, biotin-avidin systems | Nanoparticle functionalization and stabilization | Reduce non-specific binding; improve circulation half-life; enable targeting moiety attachment |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The advancement of bio-optics technologies relies on specialized research reagents and materials that enable precise manipulation of light-matter interactions at biological interfaces.

Nanoparticle Superstructures represent emerging platforms that combine nanoparticle assembly with photonic biosensing capabilities. These superstructures exhibit collective properties not present in individual nanoparticles, enabling enhanced sensitivity in detection systems integrated with deep learning algorithms for spectroscopy analysis [27].

CRISPR-Based Biosensing Platforms harness gene editing technology for diagnostic applications, capable of detecting specific nucleic acid sequences with single-base resolution. When integrated with optical or electrochemical readouts, these platforms achieve rapid, label-free detection of genetic disorders, viral mutations, and minimal residual disease, shifting diagnostics from centralized laboratories toward portable, decentralized applications [26].

Advanced Optical Materials including high-speed electro-optic modulators based on thin-film lithium niobate architectures achieve over 110 GHz bandwidth with low driving voltage, demonstrating how photonic devices originally conceived for telecommunications can be adapted for real-time biosignal processing in high-throughput genetic analysis and rapid pathogen detection [26].

The convergence of bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic therapies establishes a transformative framework for next-generation medical diagnostics and interventions. Several emerging trends will define the future trajectory of these core technology pillars.

Intelligent Adaptive Platforms will increasingly integrate artificial intelligence with biosensing and imaging to enable diagnostics that learn from each patient's data, refining both detection thresholds and therapeutic strategies in real time [26]. Advances in wearable and implantable biosensors will provide continuous molecular monitoring, adding a crucial temporal dimension to diagnostic assessments [26].

Materials Innovation will focus on smart nanomaterials that respond dynamically to disease-associated cues—releasing drugs, altering optical signatures, or modulating gene expression—bringing the field closer to closed-loop therapeutic systems [26]. The development of semimetallic and biodegradable nanoparticles will address limitations of traditional noble metal nanoparticles in terms of biocompatibility, clearance, and clinical translation.

Clinical Translation Pathways will require evolving regulatory frameworks to keep pace with these rapidly converging technologies, ensuring both safety and timely access to innovation [23]. Multifunctional platforms that combine diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities present unique regulatory challenges that must be addressed through coordinated solutions engaging academic researchers, industry partners, and regulatory bodies [23].

The integration of bio-optics technologies represents more than incremental improvement—it constitutes a fundamental shift toward precision medicine. By continuing to bridge molecular specificity, nanoscale functionality, and photonic precision, the scientific community can create diagnostic and therapeutic systems that are not only powerful but also accessible, adaptable, and truly transformative for patient care across global healthcare systems.

The field of biomedical imaging is undergoing a foundational transformation, moving beyond direct visual interpretation of images to a paradigm where computational extraction of latent information is paramount. This shift from qualitative "what you see" to quantitative "what computers reveal" is redefining the capabilities of optical technologies in biological research and drug development. Bio-optics, the science of generating and using light to interrogate biological systems, now increasingly relies on computational methods to transcend traditional physical limitations of imaging systems [2]. Where conventional imaging techniques once provided primarily morphological information, modern bio-optical systems coupled with advanced computation can reveal molecular composition, dynamic physiological processes, and functional interactions within living systems—all with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution [28] [29].

This transition is driven by the recognition that biological systems operate across multiple spatial and temporal scales, and comprehending their complexity requires analytical approaches that extend beyond human visual perception. Computational interpretation enables researchers to convert optical signals into rich, multidimensional datasets, extracting biomarkers and functional parameters that are invisible to the naked eye [2] [30]. This technical guide explores the core technologies, methodologies, and analytical frameworks powering this information-driven shift, providing researchers and drug development professionals with both theoretical foundations and practical protocols for implementation.

Core Bio-Optical Technologies and Computational Integration

Advanced Imaging Modalities: Capabilities and Limitations

The information-driven shift leverages both established and emerging bio-optical technologies, each generating unique data types requiring specialized computational interpretation methods.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Core Bio-Optical Imaging Modalities

| Technology | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Contrast Mechanisms | Primary Applications in Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | 1-15 μm | 1-3 mm | Backscattering, polarization, flow | Ophthalmology [28], cardiology [28], oncology [28] |

| Photoacoustic Tomography (PAT) | 10-500 μm | 1-5 cm | Optical absorption | Vascular imaging [28], cancer detection [28], brain imaging [28] |

| Multiphoton Microscopy | 0.3-1.0 μm | 0.5-1 mm | Two-photon excitation fluorescence, SHG, THG | Deep tissue cellular imaging [2] [31], neuronal activity [2] |

| Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) | 1-5 mm | Several cm | Luciferase-luciferin reaction | Cell tracking [31], gene expression monitoring [31], tumor growth [31] |

| Fluorescence Imaging (FLI) | 1-100 μm | 1-2 mm | Exogenous/endogenous fluorescence | Molecular targeting [31] [30], intraoperative guidance [31] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | 0.5-10 μm | 0.1-1 mm | Molecular vibrational signatures | Label-free molecular analysis [2] [14], cancer diagnostics [14] |

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) exemplifies the computational evolution in bio-optics. While conventional OCT provides structural information based on backscattered light, advanced computational techniques have enabled functional extensions including OCT angiography (OCTA), which uses moving-induced decorrelation of interference signals to image microvasculature without exogenous contrast agents [28]. Similarly, polarization-sensitive OCT (PS-OCT) computes birefringence properties to image fibrous tissues like collagen, while optical coherence elastography (OCE) calculates tissue mechanical properties by measuring displacement induced by applied pressure [28]. Each extension relies on sophisticated computational extraction of specific signal features that are not directly visible in raw OCT images.

Photoacoustic Tomography (PAT) represents a hybrid approach where optical energy absorption generates ultrasonic waves that are computationally reconstructed into images [28]. This combination provides optical contrast at ultrasonic resolution, overcoming the traditional depth limitation of pure optical microscopy. PAT's computational backbone lies in the inverse reconstruction algorithms that convert time-resolved acoustic detection into spatially resolved optical absorption maps, enabling visualization of hemoglobin concentration, oxygen saturation, and contrast agent distribution in deep tissues [28] [30].

The Space-Bandwidth Product Challenge and Computational Solutions

A fundamental limitation in conventional optical imaging is the space-bandwidth product (SBP), which defines the number of resolvable points in an image [32]. High-resolution imaging traditionally requires sacrificing field of view, while wide-field imaging compromises resolution. Computational approaches are overcoming this physical constraint through several innovative strategies:

- Spatial-domain methods capture multiple images to scale up the SBP, including array microscopy and multiscale optical imaging that tile the sample space [32].

- Frequency-domain methods augment SBP through Fourier ptychography and structured illumination microscopy, synthesizing high-resolution information from multiple low-resolution acquisitions [32].

- Wavefront-engineering methods utilize hardware- or computation-based approaches to correct lens aberrations across large fields of view [32].

These approaches collectively enable gigapixel-scale bioimaging, providing both cellular resolution and centimeter-scale fields of view—an impossibility with conventional optics alone [32]. The information capacity (N) of such systems can be quantified as N = SBP · log₂(1 + SNR), highlighting how both spatial information and signal-to-noise ratio contribute to overall system performance [32].

Computational Frameworks and Artificial Intelligence Integration

From Images to Quantitative Biomarkers

The computational interpretation of bio-optical data extends beyond image formation to the extraction of quantitative biomarkers with clinical and research significance. In OCT angiography, computational analysis transforms raw interference data into detailed vascular maps through decorrelation analysis of sequential B-scans [28]. Quantitative parameters then extracted from these maps include vessel density, foveal avascular zone area, vessel perimeter index, and branching coefficients—all providing objective measures of vascular health and pathology [28].

Similarly, in fluorescence and bioluminescence imaging, computational methods overcome limitations of these techniques through photon diffusion modeling and scatter correction algorithms to improve quantitative accuracy [31]. For bioluminescence imaging, which suffers from significant photon attenuation in tissue, 3D reconstruction algorithms incorporate optical properties of tissues to localize signal sources more accurately [31].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Quantitative Bio-Optical Analysis

| Analytical Challenge | Computational Solution | Output Parameters | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Quantification | OCTA decorrelation analysis | Vessel density, tortuosity, FAZ metrics | Diabetic retinopathy progression [28] |

| Molecular Specificity | Spectral unmixing algorithms | Concentration maps of chromophores | Oxygen saturation mapping [28] |

| Deep Tissue Localization | Photon migration models | 3D source reconstruction | Cancer metastasis tracking [31] |

| Multi-scale Integration | Image registration and fusion | Correlated structural-functional maps | Whole-brain imaging with cellular resolution [32] |

| Dynamic Process Analysis | Time-series computational analysis | Kinetic parameters, flow velocities | Neuronal activity monitoring [2] |

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have dramatically accelerated the information extraction capabilities of bio-optical technologies. These approaches are transforming every aspect of the imaging pipeline from acquisition to interpretation:

- Image Enhancement and Reconstruction: Deep learning models can reduce noise, enhance resolution, and accelerate image acquisition by reconstructing high-quality images from undersampled or low-quality data [2].

- Feature Identification and Segmentation: Convolutional neural networks automatically identify and segment biological structures in complex images, enabling high-throughput morphological analysis [2] [33].

- Predictive Modeling: ML algorithms correlate optical signatures with clinical outcomes or treatment responses, creating predictive biomarkers from complex, multidimensional optical data [2] [34].

In drug development, AI-powered analysis of bio-optical data is accelerating target validation and compound screening. The integration of cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) with optical detection methods allows researchers to confirm direct target engagement of drug candidates in biologically relevant environments [35]. AI algorithms then analyze these complex datasets to quantify drug-target interactions, providing critical insights for lead optimization [35] [34].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Quantitative OCT Angiography for Microvascular Analysis

This protocol details the acquisition and computational analysis of OCTA data for quantitative assessment of microvascular networks, particularly in retinal and dermal applications.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials:

- Spectral-Domain OCT System: Provides high-speed, high-resolution cross-sectional imaging with stable phase information [28].

- Image Processing Software: Custom algorithms for motion correction, decorrelation calculation, and vessel segmentation [28].

- Computational Framework: Software environment for quantitative parameter extraction and statistical analysis [28].

Methodology:

- System Calibration: Ensure proper alignment of spectrometer-based SD-OCT system. Verify phase stability using a stationary mirror sample.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire repeated B-scans (typically 3-5) at the same retinal position. Implement high-speed scanning (≥70,000 A-scans/second) to minimize motion artifacts between consecutive B-scans.

- Motion Correction: Apply computational motion correction algorithms based on strip-based registration and histogram-based merging to eliminate tissue motion artifacts.

- Decorrelation Calculation: Compute decorrelation between consecutive B-scans using the formula: D = 1 - (I₁·I₂)/((I₁² + I₂²)/2), where I₁ and I₂ represent intensity values from sequential B-scans.

- Projection-Resolved Processing: Apply specialized algorithms to distinguish flowing elements at different depths, preserving the 3D vascular architecture.

- Vessel Segmentation: Use adaptive thresholding and machine learning-based classification to distinguish vascular elements from noise and static tissue.