Bio-Optics 2025: A Comprehensive Guide to Design, Applications, and Future Trends in Biomedical Light Technologies

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a current and in-depth exploration of bio-optics, the field leveraging light-based technologies for biological and medical applications.

Bio-Optics 2025: A Comprehensive Guide to Design, Applications, and Future Trends in Biomedical Light Technologies

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a current and in-depth exploration of bio-optics, the field leveraging light-based technologies for biological and medical applications. It covers foundational principles, core technologies like Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Raman spectroscopy, and their transformative applications in cancer diagnostics, infectious disease detection, and minimally invasive surgery. The content also addresses key optimization strategies, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), and provides a comparative analysis of emerging technologies and market trends to guide research and development decisions in this rapidly advancing field.

The Principles and Expanding Scope of Bio-Optics

Bio-optics and biophotonics represent a dynamic interdisciplinary frontier that merges the principles of optics and photonics with biology and medicine. This field utilizes light-based technologies to analyze, detect, and manipulate biological materials, driving innovations across medical diagnostics, therapeutics, and fundamental research [1]. While the terms are often used interchangeably, biophotonics broadly encompasses the interaction of light with biological matter, including the development of tools for imaging, sensing, and therapy [2] [3]. In contrast, bio-optics often refers more specifically to the design and application of optical instruments and systems for solving biological problems, a focus reflected in specialized conferences like the Optica Bio-Optics: Design and Application (BODA) meeting [4]. The core of this discipline lies in understanding fundamental light-biological matter interactions—such as absorption, emission, fluorescence, and scattering—and leveraging this knowledge to develop technologies that provide high spatial and temporal resolution for observing biological processes in real-time [2] [5]. This technical guide outlines the core principles, advantages, and methodologies of bio-optics and biophotonics, framed within the context of advanced design and application research.

Core Concepts and Fundamental Interactions

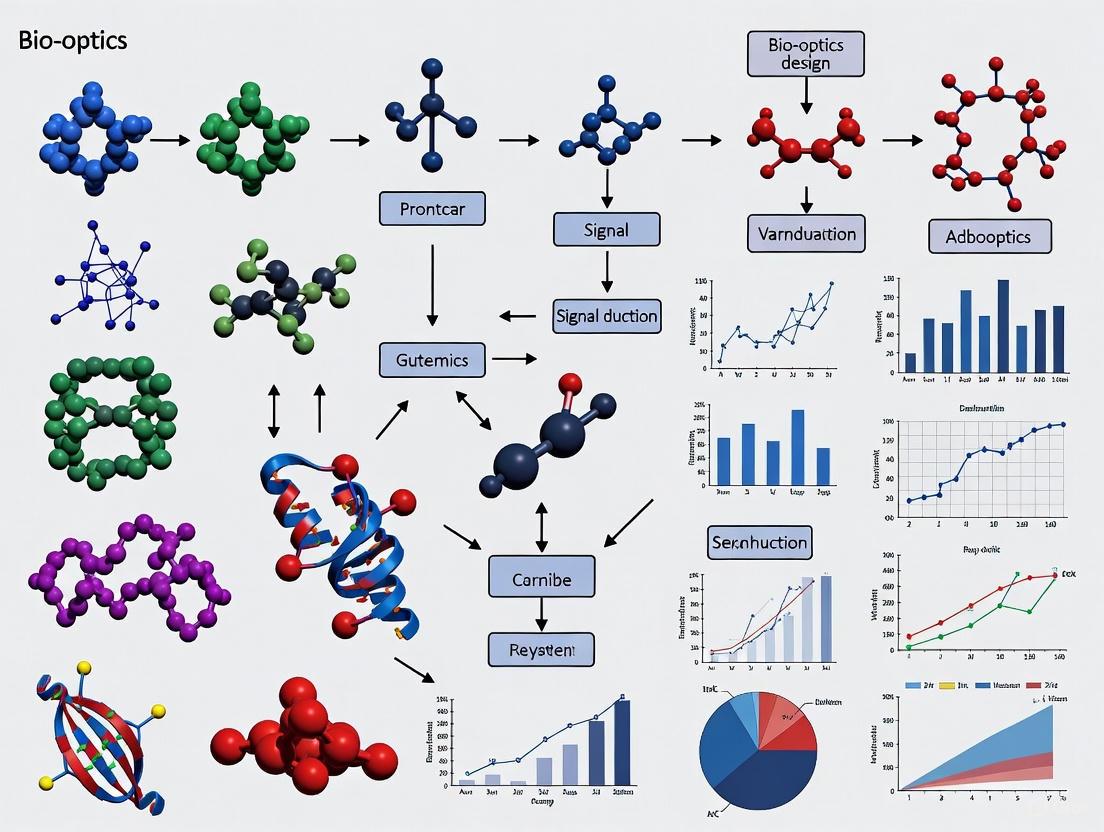

The theoretical foundation of biophotonics rests on the interactions between photons and biological components, ranging from single molecules to entire tissues. The following diagram illustrates the primary physical phenomena that occur when light interacts with biological matter.

Light-Biology Interaction Mechanisms

Absorption and Emission: When biological molecules absorb photons, they enter an excited state. Upon returning to ground state, they may emit light through processes like fluorescence or phosphorescence [5]. This principle is harnessed in fluorescence microscopy, where specific fluorophores are used to label and visualize cellular components, enabling the study of dynamic processes in living cells.

Scattering: Light can be elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering) or inelastically scattered (Raman scattering) by biological tissues. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) leverages back-scattered light to generate high-resolution, cross-sectional images of tissue morphology in real-time, making it invaluable in ophthalmology and cardiology [6] [7].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): This label-free biosensing technique detects changes in the refractive index near a metal surface, allowing researchers to monitor biomolecular interactions—such as antigen-antibody binding—in real-time without the need for fluorescent labeling [5].

Key Advantages and Technological Benefits

Biophotonic technologies offer significant advantages over conventional methods in biological research and clinical practice, which can be summarized in the following table.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Biophotonic Technologies

| Advantage | Technical Description | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasiveness & High Resolution | Enables visualization of biological structures and processes in vivo without causing damage, with resolutions down to the cellular and molecular level [2] [7]. | Real-time cellular imaging, in vivo functional brain mapping, tumor microenvironment studies [7]. |

| Minimally Invasive Therapeutics | Replaces conventional surgery through endoscopic delivery of light via flexible optical fibers, reducing patient pain and recovery time [3]. | Laser endoscopic surgery, photodynamic therapy (PDT), intraluminal calculi removal [3]. |

| Precision and Specificity | Allows for targeted interaction with specific tissues or molecules through control of light parameters like wavelength and intensity [3] [1]. | Laser tissue processing (incision, coagulation), selective tumor excision, optogenetics [3]. |

| Rapid, Real-Time Analysis | Provides immediate feedback and monitoring of biological processes, enabling rapid diagnostics and dynamic study of cellular functions [2] [7]. | Point-of-care biosensing, surgical guidance, monitoring of cellular dynamics and drug responses [7]. |

These advantages collectively contribute to the transformative impact of biophotonics. The technology facilitates a reduction in treatment times, minimizes surgical trauma and blood loss through high-temperature laser incision that seals small blood vessels, and provides unparalleled precision for both diagnostic and therapeutic interventions [3]. The integration of optical fibers allows light to be delivered to previously inaccessible areas of the body through natural openings or small incisions, fundamentally changing surgical approaches [3] [6].

Essential Optical Components and Research Tools

The advancement of biophotonics relies on a suite of core optical components that enable the generation, manipulation, and detection of light for biological applications. The table below details these essential tools and their functions within the researcher's toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Optical Components in Biophotonics Research

| Optical Component | Primary Function | Specific Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lasers | Emit high-intensity, coherent light at specific wavelengths and intensities [6] [1]. | Tissue ablation, coagulation, cell manipulation, optical tweezers, flow cytometry [3] [6]. |

| Imaging Systems | Visualize and observe cellular and tissue structures and functions [6] [1]. | Confocal microscopy, multiphoton microscopy, super-resolution imaging, optical coherence tomography [6] [5]. |

| Fiber Optics | Deliver light precisely into tissues and enable light transmission within living organisms [6] [1]. | Endoscopic imaging and surgery, light delivery in photodynamic therapy, in vivo sensing [3] [6]. |

| Spectrometers | Analyze the wavelength and intensity of light [6] [1]. | Measuring fluorescence and absorption spectra, Raman spectroscopy, characterizing biological samples [6]. |

Customization of these optical systems is a critical trend, allowing researchers to optimize parameters such as resolution, wavelength, and power for specific experimental needs. This customization enhances performance, provides greater experimental flexibility and control, and improves cost-efficiency by eliminating unnecessary features [1]. For instance, custom-designed imaging systems can be developed to provide high resolution within specific wavelength ranges crucial for particular fluorescence markers.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vitro Cell Imaging Using Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy is a cornerstone technique for visualizing the localization and dynamics of specific molecules within cells.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Fluorescence Microscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Dyes or Proteins | Bind to or are expressed by cellular targets to provide contrast. | GFP (Genetic Encoding), FITC (Antibody Conjugation), Hoechst stains (Nuclear DNA) [5]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Buffers | Maintain cell viability and provide a physiological environment during imaging. | Phenol-free medium (to reduce background fluorescence), PBS for washing [5]. |

| Fixation and Permeabilization Agents | Preserve cell structure and enable dye access to intracellular targets (for fixed cells). | Paraformaldehyde (fixation), Triton X-100 (permeabilization) [5]. |

| Mounting Medium | Preserve samples under coverslips for high-resolution imaging. | Antifading agents to reduce photobleaching [5]. |

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Culture cells on sterile, glass-bottomed dishes. For fixed cell imaging, treat cells with a fixative (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde) followed by a permeabilization agent if labeling internal targets. Incubate with specific primary antibodies and then with fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies. For live-cell imaging, use cells expressing genetically encoded fluorescent proteins like GFP.

- Microscope Setup: Configure the fluorescence microscope (widefield, confocal, or multiphoton). Select appropriate excitation and emission filters matched to the spectral properties of the fluorophores used. For confocal microscopy, set the pinhole aperture to optimize optical sectioning and signal-to-noise ratio.

- Image Acquisition: Illuminate the sample with the specific excitation wavelength. The emitted light from the fluorophores is captured by a high-sensitivity detector (e.g., PMT or CCD camera). For live imaging, control environmental factors (temperature, CO₂). Minimize light exposure to prevent phototoxicity and photobleaching.

- Image Analysis: Use software to process acquired images for tasks like colocalization analysis, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to monitor molecular interactions, or fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to study protein mobility [5].

Protocol: In Vivo Tumor Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

PDT is a clinically approved biophotonic therapy that combines light, a photosensitizer, and tissue oxygen to selectively destroy target cells [3]. The workflow is complex, integrating pharmacokinetics, light delivery, and therapeutic action, as shown in the following diagram.

Methodology:

- Photosensitizer Administration: A light-sensitive chemical (photosensitizer) is administered to the patient intravenously or topically. The photosensitizer is designed to be preferentially absorbed and retained by rapidly dividing tumor cells compared to healthy tissue [3].

- Drug-Tissue Interval: A specific time interval (ranging from hours to days) is allowed for the photosensitizer to clear from normal tissues and accumulate in the target tumor tissue.

- Light Application: The target tumor is irradiated with light of a specific wavelength (typically in the near-infrared range for deeper tissue penetration) that corresponds to the absorption peak of the photosensitizer. This light can be delivered via optical fibers or specialized light sources [3] [6].

- Therapeutic Action: The activated photosensitizer interacts with molecular oxygen in the tissue, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen. These highly cytotoxic species induce oxidative damage to cellular components, leading to targeted cancer cell death, vascular damage within the tumor, and an associated inflammatory response [3].

Future Outlook and Emerging Trends

The field of bio-optics and biophotonics is poised for significant evolution, driven by several converging technological trends. A major growth area is the development of miniaturized and portable devices, including handheld imaging probes and wearable biosensors, which facilitate point-of-care diagnostics and continuous health monitoring [2] [7]. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is revolutionizing data analysis, enhancing image reconstruction, automated lesion detection, and the interpretation of complex biological data, thereby improving diagnostic accuracy and speed [2] [4] [8].

Furthermore, the fusion of biophotonics with nanotechnology is leading to the creation of novel biophotonic nanostructures and nanophotonic biosensors. These advancements enable ultrasensitive tracking of biomarkers and pathogens, opening new avenues for early-stage disease detection and personalized medicine [7] [9]. Research is also advancing novel therapeutic applications, such as optogenetics for precise neural stimulation and the use of NIR phototherapy for wound healing and tissue repair [3] [7]. Despite the promising outlook, the field must overcome challenges related to high equipment costs, the need for specialized training, limited optical penetration depth in tissues, and the complexities of regulatory approval and clinical translation [7] [9]. Ongoing research and interdisciplinary collaboration are crucial to addressing these hurdles and fully realizing the potential of biophotonics in advancing healthcare and biological research.

This document serves as an in-depth technical guide to the fundamental principles of light-matter interactions, framed within the context of bio-optics design and application research. Biophotonics—the interdisciplinary fusion of light-based technologies with biology and medicine—is rapidly transforming scientific research, diagnostics, and therapy [10]. At its core, biophotonics involves the use of light to analyze and manipulate biological materials, providing a powerful tool for understanding and influencing life processes at the molecular, cellular, tissue, and organ levels [10]. The field leverages key optical phenomena, including absorption, emission, scattering, and reflection, to enable groundbreaking applications in bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic-based therapies [10]. This whitepaper provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed examination of these core interactions, their quantitative descriptors, associated experimental methodologies, and the essential reagents and materials required for their investigation in a biological context.

Fundamental Interactions and Quantitative Parameters

When a photon interacts with an atom or molecule, three primary outcomes are possible: elastic scattering, inelastic interaction, or absorption with energy dissipation [11]. The following sections detail these phenomena and their quantitative measures, which are critical for designing bio-optical instruments.

Absorption

Absorption occurs when a photon is absorbed by a molecule, causing an electron to move from its ground state to a higher, excited state [11]. The excited state could be virtual or a quantum level permitted for the molecule, depending on the photon's energy and the difference between the molecular energy levels [11]. At a microscopic scale, absorption is described by the polarizability (P) of the media in response to the optical field (E) via the electrical susceptibility (χ) [11]. Macroscopically, absorption manifests as attenuation of light intensity, governed by the Beer-Lambert law [11]. The absorption coefficient (μₐ) is a key parameter that depends on the wavelength of light and the complex-valued refractive index at the incident wavelength [11].

Emission

Emission processes involve the release of energy as photons when excited electrons relax to lower energy states. A key emission phenomenon is fluorescence, which occurs when an absorbing electron relaxes from its excited state and releases energy as a photon [11]. During the nanosecond-scale excited state, some energy dissipates through vibrational relaxation, resulting in the emitted photon having a longer wavelength than the absorbed photon—a phenomenon known as the Stokes shift [11]. The time lag between excitation and emission is the fluorescence lifetime, which exhibits a temporal profile of exponential decay [11]. Fluorophores possess unique absorption and emission spectra and fluorescence lifetimes that are generally dependent on their chemistry and can be altered by their environment [11].

Scattering

Scattering refers to any interaction that changes the trajectory of light and is responsible for phenomena such as the twinkling of stars and the turbidity of milk [11]. Scattering can be elastic, where the excitation and emission wavelengths are identical, or inelastic [11]. The scattering coefficient (μₛ) is often combined with the absorption coefficient in modified versions of the Beer-Lambert law [11]. Scattering mechanisms are categorized based on particle size relative to the wavelength of light, with three primary types being Rayleigh scattering (particle size ≤ wavelength), Mie scattering (particle size 1-10× wavelength), and geometric scattering (particle size >> wavelength) [11]. For Mie scattering by particles typically 1-10 times the wavelength of light, over 90% of the light is forward scattered and 1-5% is back-scattered [11].

Reflection

Reflection is a fundamental light-matter interaction where light bounces off a surface or interface between two media. In the context of biophotonics, reflection is often considered alongside scattering phenomena, as both involve changes in light direction without alteration of its energy [11]. Reflection plays a crucial role in various bio-optical techniques, particularly in surface-based imaging and sensing applications where light interacts with tissue interfaces or sensor surfaces.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Light-Matter Interactions in Bio-optics

| Interaction Type | Governing Law/Principle | Key Quantitative Parameter(s) | Biological Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Beer-Lambert Law | Absorption Coefficient (μₐ) | Measuring chromophore concentration (e.g., hemoglobin, melanin) [11] |

| Emission | Exponential decay kinetics | Fluorescence Lifetime, Quantum Yield | FRET imaging, cellular environment sensing, molecular tracking [11] |

| Scattering | Mie, Rayleigh theories | Scattering Coefficient (μₛ), Anisotropy (g) | Optical coherence tomography, tissue characterization [11] [10] |

| Reflection | Fresnel Equations | Reflectance, Refractive Index | Surface topography imaging, ellipsometry-based biosensing [11] |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for measuring and characterizing the fundamental light-matter interactions discussed previously, with a focus on techniques relevant to bio-optics research.

Protocol 1: Measuring Absorption Spectra of Biological Chromophores

Objective: To determine the absorption characteristics and concentration of biological chromophores (e.g., hemoglobin, NADH, melanin) in solution or tissue samples.

Materials Required:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with cuvette holder or integrating sphere for turbid samples

- Quartz cuvettes (for UV transmission)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or appropriate buffer

- Standard solutions of target chromophores for calibration

- Biological samples (tissue homogenates, cell lysates, or purified chromophore solutions)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- For solution measurements, dilute samples in appropriate buffer to achieve optical densities between 0.1 and 1.0 for optimal measurement accuracy.

- For turbid samples (tissue sections, cell suspensions), use an integrating sphere attachment to account for both absorption and scattering contributions.

Instrument Calibration:

- Perform baseline correction with blank buffer solution.

- Measure absorption spectra of standard solutions to create a calibration curve.

Data Acquisition:

- Set spectrophotometer to scan from 250 nm to 800 nm or the relevant spectral range.

- Record absorption spectra of all samples, averaging multiple scans to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

Data Analysis:

- Apply Beer-Lambert law: A = ε × c × l, where A is absorbance, ε is molar absorptivity, c is concentration, and l is path length.

- For turbid samples, use modified Beer-Lambert law incorporating scattering correction factors.

Expected Outcomes: Absorption spectra showing characteristic peaks for target chromophores, enabling quantification of concentration and purity assessment.

Protocol 2: Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Objective: To measure fluorescence lifetimes and characterize molecular environments and interactions in biological systems.

Materials Required:

- Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) system or streak camera system

- Pulsed laser source (wavelength matched to fluorophore excitation)

- Fluorophore-labeled biomolecules (proteins, nucleic acids)

- Reference fluorophore with known lifetime for instrument response calibration

- Temperature-controlled sample chamber

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Align excitation and emission pathways, ensuring proper collection optics and filters.

- Measure instrument response function using a reference scatterer or fluorophore with known lifetime.

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare fluorophore-labeled biomolecules in appropriate physiological buffer.

- Degas samples if necessary to reduce oxygen quenching effects.

Data Acquisition:

- Set appropriate laser power and acquisition time to avoid photobleaching and pile-up effects.

- Collect fluorescence decay curves at multiple emission wavelengths if performing lifetime-resolved measurements.

Data Analysis:

- Fit decay curves to single or multi-exponential models: I(t) = Σαᵢexp(-t/τᵢ), where τᵢ are lifetime components and αᵢ are their amplitudes.

- Calculate average lifetime: <τ> = Σαᵢτᵢ² / Σαᵢτᵢ

Expected Outcomes: Fluorescence lifetime values that provide information about local environment, molecular interactions, and conformational changes of biomolecules.

Protocol 3: Quantifying Light Scattering in Biological Tissues

Objective: To characterize scattering properties of biological tissues for optical tomography and spectroscopy applications.

Materials Required:

- Integrating sphere spectrophotometer

- Tissue samples (fresh or preserved) of controlled thickness

- Index-matching fluids

- Thin-sectioning microtome

- Calibrated reflectance standards

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare tissue sections of known thickness (typically 100-500 μm) using a microtome.

- Mount samples between glass slides with index-matching fluid if necessary.

System Calibration:

- Calibrate integrating sphere using reflectance standards with known reflectance values.

- Measure baseline with no sample.

Data Acquisition:

- Measure total transmission (T), collimated transmission (T꜀), and reflectance (R) of tissue samples.

- Perform measurements at multiple wavelengths relevant to application (typically 400-1000 nm).

Data Analysis:

- Use inverse adding-doubling method to extract absorption (μₐ) and reduced scattering (μₛ') coefficients from T and R measurements.

- Calculate anisotropy factor (g) from collimated and total transmission measurements.

Expected Outcomes: Wavelength-dependent absorption and scattering coefficients that inform light transport models for tissue optics applications.

Diagram 1: Tissue scattering measurement workflow

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful investigation of light-matter interactions in biological systems requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key components of the "Researcher's Toolkit" for bio-optics experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bio-optics Investigations

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Chromophores | Hemoglobin, NADH, FAD, Melanin | Endogenous absorbers; natural contrast agents in label-free imaging [10] | Characteristic absorption spectra; concentration-dependent contrast |

| Exogenous Fluorophores | GFP, RFP; Alexa Fluor dyes; ICG | Fluorescent labeling for molecular tracking and environment sensing [11] | High quantum yield; photostability; specific excitation/emission profiles |

| Quantum Dots | CdSe/ZnS core-shell nanoparticles | Photostable fluorescent probes for long-term imaging and multiplexing | Size-tunable emission; broad absorption; narrow emission spectra |

| Scattering Phantoms | Polystyrene microspheres; TiO₂ suspensions | Calibration standards for optical instruments; tissue simulating phantoms | Well-defined size distribution; known scattering properties |

| Nonlinear Crystals | BBO, KTP crystals | Frequency conversion for multiphoton microscopy (SHG, THG) [10] | High nonlinear coefficients; appropriate phase-matching properties |

| Optical Clearing Agents | FocusClear, ScaleS | Reduce scattering in tissue for improved imaging depth | Refractive index matching; tissue compatibility |

| Biosensor Constructs | FRET-based molecular tension sensors; GECIs | Reporting specific molecular activities or ionic concentrations | Specific targeting; dynamic response to biochemical changes |

Advanced Technical Considerations in Bio-optics

Modern biophotonics research extends beyond basic interactions to leverage advanced phenomena and computational approaches for enhanced biological insight.

Linear vs. Nonlinear Interactions

Recent advances in the development of compact and easy-to-operate high-intensity ultrashort laser sources have enabled the exploitation of nonlinear optical phenomena for biomedical imaging, resulting in significant improvements in penetration depth, optical resolution, and acquisition speed [10]. In linear interactions, the response of the material is proportional to the incident light field, whereas nonlinear interactions depend on higher powers of the electric field strength and enable phenomena such as multiphoton absorption, second harmonic generation (SHG), and third harmonic generation (THG) [10]. Multi-photon imaging using near IR (NIR) femtosecond lasers provides high penetration depths, allowing the study of biological tissue with high spatial resolution and good contrast not only on the surface but also deep within the tissue [10].

Molecular Specificity and Contrast Mechanisms

The contrast mechanisms underlying biophotonic methods can be highly molecule-specific in the case of IR absorption and Raman scattering [10]. These techniques can visualize native electronic chromophores such as hemoglobin, NADP(H), flavin, elastin, or cytochrome by absorption (hyperspectral imaging or photoacoustic imaging) or emission (autofluorescence or fluorescence label imaging) [10]. Specific structural proteins (e.g., collagen) can be visualized by SHG, while changes in refractive index are detected by optical coherence tomography (OCT) and phase boundaries by THG [10]. Molecular contrast is highest when spectroscopic data are acquired, as in hyperspectral imaging, fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM), spontaneous or coherent Raman spectroscopy, or IR absorption spectroscopy [10].

Diagram 2: Electronic transitions in light-matter interactions

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Biophotonics

In the recent decade, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) have played an increasingly transformative role in biophotonics by enhancing data analysis, interpretation, and optimization of complex imaging and sensing [4]. AI approaches are being applied to improve image reconstruction, interpret complex biological patterns, and even optimize optical design itself [4]. These computational methods are particularly valuable for extracting meaningful biological information from the complex datasets generated by techniques such as hyperspectral imaging, OCT, and Raman spectroscopy, where traditional analysis methods may be insufficient for fully leveraging the rich information content.

The fundamental light-matter interactions of absorption, emission, scattering, and reflection form the foundation upon which modern bio-optics and biophotonics are built. Understanding these core principles at both quantitative and mechanistic levels enables researchers to design increasingly sophisticated instruments for biological discovery and medical application. As the field continues to evolve through integration with artificial intelligence, novel materials, and quantum approaches, these basic interactions will remain central to extracting meaningful biological information from light. The methodologies and resources detailed in this technical guide provide a foundation for researchers to investigate and apply these principles in their own work, contributing to the advancement of bio-optics design and application research with potential impacts across basic science, clinical diagnostics, and therapeutic development.

Bio-optics and its closely related field, biophotonics, represent the convergence of light-based technologies with biological and medical sciences. This discipline utilizes light to image, analyze, and manipulate biological materials, driving advancements in research, diagnostics, and therapeutics [10]. The market for these technologies is experiencing significant global growth, fueled by the increasing demand for non-invasive diagnostic tools, minimally invasive surgical procedures, and advanced research applications in drug discovery and life sciences [12] [13] [14]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of the market landscape, detailing projected growth rates, key drivers, dominant sectors, and the essential methodologies and tools that underpin this dynamic field. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it frames this commercial and technological landscape within the broader context of bio-optics design and application research.

The global market for bio-optics and biophotonics is on a strong growth trajectory, though reported valuations vary depending on the specific definition and scope of the market segments. The table below summarizes key quantitative projections from recent analyses.

Table 1: Global Market Size and Growth Projections for Bio-optics and Biophotonics

| Market Segment | Base Year & Value (USD) | Projected Year & Value (USD) | CAGR | Source & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-optics | 2024: 2.03 Billion [12] | 2032: 3.31 Billion [12] | 6.3% (2025-2032) [12] | "Bio Optics Market" report [12] |

| Bio-optics | 2022: 1.2 Billion [15] | 2031: 2.1 Billion [15] | 6.0% (2023-2031) [15] | "Bio-optics Market" report [15] |

| Biophotonics | 2024: 76.1 Billion [13] | 2034: 220.1 Billion [13] | 11.3% (2025-2034) [13] | "Biophotonics Market" report [13] |

| Biophotonics | 2024: 62.6 Billion [14] | 2030: 113.1 Billion [14] | 10.6% (2025-2030) [14] | BCC Research report [14] |

The disparity in market values between "bio-optics" and "biophotonics" reports suggests that the latter may encompass a broader range of light-based technologies in life sciences. Despite different baselines, both sectors demonstrate robust growth, with CAGRs consistently exceeding 6% and reaching over 11% for the biophotonics segment [12] [13] [14]. Regionally, North America, particularly the United States, holds the dominant market share, attributed to its advanced healthcare infrastructure, significant R&D investments, and the presence of leading industry players [12] [13] [14]. Europe is also a major market, with Germany and the UK being key contributors, while the Asia-Pacific region, led by China and India, is expected to witness the fastest growth [13] [15].

Key Market Growth Drivers

The expansion of the bio-optics market is propelled by several interconnected factors:

- Demand for Non-Invasive Diagnostics and Minimally Invasive Surgeries: There is a strong clinical and patient preference for procedures that reduce discomfort, risk, and recovery time. Bio-optics technologies, such as Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and advanced endoscopy, are crucial for guiding and monitoring these procedures, thereby boosting market growth [12] [15] [14].

- Rising Prevalence of Chronic Diseases and Aging Populations: The increasing global burden of chronic conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes is driving the need for advanced diagnostic and therapeutic tools. Furthermore, the aging global population, which is more susceptible to these conditions, creates a sustained demand for these technologies [13] [15].

- Technological Advancements and Convergence: Continuous innovation in optical technologies, including the development of novel fluorescent probes, super-resolution microscopy, and portable devices, is expanding the capabilities and applications of bio-optics. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning for image analysis and data interpretation is enabling quicker, more reliable diagnoses and is a key trend shaping the market [10] [13] [15].

- Expansion into Point-of-Care and Personalized Medicine: There is a growing emphasis on decentralizing healthcare and bringing diagnostics closer to patients. Portable and handheld bio-optics devices facilitate point-of-care testing, while the capabilities of these technologies for molecular-level analysis align perfectly with the trend towards personalized and precision medicine [12] [13] [14].

Dominant Market Sectors and Applications

The bio-optics market can be segmented by technology, device, and application, with certain segments demonstrating clear dominance.

By Technology and Device

Table 2: Dominant Segments by Technology and Device

| Segment Category | Dominant Segment | Key Applications and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Technology | Raman Spectroscopy [12] | Provides detailed molecular information for studying cell and tissue composition, identifying disease biomarkers, and monitoring drug interactions without extensive sample preparation. |

| Device | Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) [12] | A non-invasive imaging technique that captures high-resolution, cross-sectional images of biological tissues in real-time. It is well-established in ophthalmology and expanding into cardiology, dermatology, and oncology. |

| Imaging Modality | See-Through Imaging [13] [7] | This segment, which includes techniques like OCT, is growing at the highest CAGR. It provides non-invasive, high-resolution visualization of internal anatomical structures, crucial for early disease detection and surgical guidance. |

By Application

The most prominent application sector for bio-optics is medical diagnostics, with cancer diagnostics representing the largest sub-segment [12] [16] [14]. Bio-optics technologies are indispensable in the fight against cancer, enabling early detection, accurate staging, and personalized treatment planning. Techniques like OCT, fluorescence imaging, and Raman spectroscopy are used to detect and characterize cancer cells, assess tumor margins, and monitor treatment responses [12]. The detection of infectious diseases is another critical application area, where optical biosensors and advanced imaging offer rapid and sensitive pathogen detection, a need highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic [16] [7].

Core Experimental Methodologies in Bio-optics

For researchers designing and applying bio-optics tools, understanding core methodologies is essential. Below are detailed protocols for three key techniques.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) for Tissue Imaging

OCT is a label-free technique that uses interferometry to generate high-resolution, cross-sectional images of scattering biological tissues [10].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Tissue samples (e.g., retinal, arterial, or skin) can be imaged in vivo or ex vivo. For in vivo human imaging, such as in ophthalmology, no physical preparation is needed. For ex vivo studies, tissues are typically fixed and stored in appropriate buffers to preserve morphology.

- System Setup: A broadband low-coherence light source (e.g., a super-luminescent diode) is split into a reference arm and a sample arm via a beamsplitter.

- Data Acquisition: Light backscattered from the sample and reflected from the reference mirror recombines at the detector, creating an interferometric signal. This signal is digitized as a function of optical wavelength.

- Image Processing: The digitized interferogram is processed via a Fourier transform to reconstruct the depth-resolved reflectivity profile (A-scan). Multiple A-scans are acquired by scanning the beam across the sample to build a 2D cross-sectional image (B-scan).

- Analysis: The resulting B-scan image reveals tissue microstructure, allowing for the identification of layers, abnormalities, or specific morphological features based on differences in optical scattering.

Raman Spectroscopy for Molecular Analysis

Raman spectroscopy probes the vibrational state of molecules, providing a highly specific chemical fingerprint of a sample based on inelastic scattering of light [12] [10].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Biological samples (cells, tissues, biofluids) can be analyzed with minimal preparation, often requiring no labels or stains. Cells may be cultured on suitable substrates, and tissues are typically sectioned.

- System Setup: A monochromatic laser source is focused onto the sample through a microscope objective. A spectrometer equipped with a sensitive CCD detector is used to collect the scattered light.

- Data Acquisition: The Raman scattered light is collected and its spectrum is dispersed. The intrinsic weakness of the Raman signal is a key challenge. This can be overcome by using nonlinear coherent Raman scattering (CRS) phenomena like CARS or SRS, which enhance the signal [10].

- Spectral Processing: Acquired spectra are processed to remove background fluorescence and noise, and may be normalized for comparative analysis.

- Analysis: The resulting spectrum shows peaks corresponding to specific molecular vibrations. Multivariate statistical analysis or machine learning algorithms can be applied to identify biochemical differences between sample groups (e.g., healthy vs. diseased tissue) [13].

Fluorescence Imaging for Cellular and Molecular Visualization

This technique uses the property of fluorescence to visualize the spatial distribution of specific molecules or ions within cells and tissues [12] [10].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation and Labeling:

- Option A (Labeled): Introduce exogenous fluorescent probes, such as organic dyes or antibodies conjugated to fluorophores, that target specific structures (e.g., actin, nuclei) or biomarkers.

- Option B (Label-free): Utilize endogenous fluorophores (e.g., NAD(P)H, flavins) for autofluorescence imaging [10].

- Option C (Genetically Encoded): Transfert cells with genes encoding fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) fused to proteins of interest.

- System Setup: An epifluorescence or confocal microscope is used, equipped with a light source for excitation (e.g., laser, LED), a set of optical filters (excitation, emission, dichroic), and a high-sensitivity detector.

- Data Acquisition: The sample is illuminated with light at the excitation wavelength. The emitted fluorescence light, at a longer wavelength, is collected through the objective and filtered to block excitation light before being detected.

- Image Processing: Background subtraction, flat-field correction, and deconvolution algorithms may be applied to improve image quality and resolution.

- Analysis: Images are analyzed to determine the localization, concentration, and dynamics of the target molecules. Techniques like FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer) can be used to monitor molecular interactions.

Diagram 1: Fluorescence imaging workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful bio-optics experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components of the researcher's toolkit.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Bio-optics

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes & Dyes | To label and visualize specific biological structures, ions, or molecules. | Organic dyes (e.g., Cyanine, Alexa Fluor), cell-permeant dyes for organelles, ion indicators (e.g., Ca²⁺ dyes). |

| Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins | To tag and track proteins in live cells via genetic engineering. | Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP) [12]. Enable long-term live-cell imaging. |

| Antibodies (Conjugated) | For highly specific immunolabeling of target antigens in fixed cells/tissues. | Antibodies conjugated to fluorophores for immunofluorescence microscopy. |

| Nanoparticles and Quantum Dots | Act as contrast agents or sensors, often offering superior brightness and photostability. | Metallic nanoparticles, quantum dots [13]. Used in biosensing and super-resolution imaging. |

| Biosensors (Optical) | Detect the presence or concentration of a biological analyte by converting a biological response into an optical signal. | Utilize principles like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or FRET for label-free detection of biomolecules [7]. |

| Live Cell Imaging Media | To maintain cell viability and function during prolonged imaging on a microscope stage. | Phenol-red free formulations (to reduce background), with buffers to maintain pH. |

Diagram 2: Biophotonic biosensor operating logic.

The bio-optics and biophotonics market is positioned for sustained, robust growth, driven by relentless technological innovation and critical unmet needs in healthcare and life sciences. Key sectors such as cancer diagnostics, powered by technologies like OCT and Raman spectroscopy, will continue to dominate and evolve. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the core experimental protocols—from foundational fluorescence imaging to advanced label-free techniques—is essential for leveraging the full potential of this field. The ongoing integration of AI, the development of novel reagents and nanomaterials, and the push toward point-of-care applications will undoubtedly shape the next generation of bio-optics design and research, solidifying its role as a cornerstone of modern precision medicine.

Biophotonics, the interdisciplinary fusion of light-based technologies with biology and medicine, has emerged as a transformative force in 21st-century science and healthcare [10]. This field, derived from the Greek words "bios" (life) and "phos" (light), focuses on understanding how light interacts with biological matter to advance fundamental research, diagnostics, and therapeutic interventions [10]. The core technology areas of bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic therapies represent the foundational pillars of biophotonics, enabling unprecedented capabilities for analyzing and manipulating biological systems from the molecular to organism level. These technologies leverage key advantages of light, including non-contact measurement, rapid information acquisition, exceptional sensitivity down to single-molecule detection, and high temporal resolution for observing dynamic biological processes [10].

The integration of these core areas is driving innovation across numerous domains, from pharmaceutical development and clinical medicine to environmental monitoring and agriculture [10]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of each core technology area, focusing on their operating principles, current applications, methodological protocols, and future directions within the broader context of bio-optics design and application research. As the field continues to evolve through convergence with artificial intelligence, novel materials, and quantum technologies, bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic therapies are poised to become increasingly central to precision medicine and the One Health approach [10].

Bioimaging Technologies and Methodologies

Fundamental Principles and Modalities

Bioimaging encompasses a diverse suite of photonic technologies that enable the characterization of biological specimens across multiple spatial scales, from nanoscopic investigation of intracellular interactions to macroscopic imaging of tissues and organ systems [10]. These techniques are fundamentally based on the interaction of light with biological matter through processes of absorption, emission, scattering, and reflection, which elucidate morphological and molecular details across resolution scales [10]. The most representative label-free biophotonic diagnostic methods include hyperspectral imaging (HSI), fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM), second and third harmonic generation (SHG, THG), optical coherence tomography (OCT), diffuse remission spectroscopy (DRS), photoacoustic imaging (PAI), and vibrational microspectroscopy (IR absorption and Raman scattering) [10].

A critical distinction in bioimaging technologies lies between linear and nonlinear light-matter interaction phenomena. Recent advances in compact high-intensity ultrashort laser sources have enabled the exploitation of nonlinear optical phenomena for biomedical imaging, resulting in significant improvements in penetration depth, optical resolution, and acquisition speed [10]. Multi-photon absorption, for instance, provides precise localization of fluorescence or harmonic generation signals since such nonlinear processes occur only in extremely small volumes, offering superior imaging capabilities deep within biological tissues [10].

Table 1: Major Bioimaging Technologies and Their Characteristics

| Imaging Technology | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Applications | Contrast Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | 1-15 μm | 1-2 mm | Ophthalmology, tissue morphology | Refractive index changes |

| Multi-Photon Microscopy | 0.2-0.8 μm | 0.5-1 mm | Deep tissue cellular imaging | Nonlinear excitation |

| Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI) | 20-200 μm | 2-5 cm | Vascular imaging, oncology | Light absorption → ultrasound |

| Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) | 0.3-1 μm | Single cell to tissue | Metabolic monitoring, molecular environment | Fluorescence decay rates |

| Coherent Raman Scattering (CRS) | 0.3-0.5 μm | 0.2-0.5 mm | Label-free molecular imaging | Molecular vibrations |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Modal Imaging of Tissue Structures

Objective: To characterize tissue morphology and molecular composition using a combined OCT and SHG imaging approach for distinguishing pathological from healthy tissues.

Materials and Equipment:

- Spectral-domain OCT system with near-infrared light source (center wavelength ~1300 nm)

- Femtosecond laser system tuned for SHG imaging (typical wavelength ~800 nm)

- High-numerical aperture objectives suitable for both OCT and nonlinear microscopy

- Precision motorized sample stage for co-registered imaging

- Biological specimens (tissue sections or in vivo preparations)

- Data acquisition and processing workstation with specialized software

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Align OCT and SHG optical paths to ensure precise spatial registration between modalities. Adjust laser power levels to ensure biological safety thresholds are maintained, especially for in vivo applications.

Sample Preparation: For ex vivo imaging, prepare tissue sections of appropriate thickness (typically 100-500 μm) and mount using compatible media. For in vivo imaging, properly position the subject and stabilize the region of interest.

OCT Data Acquisition: Acquire volumetric OCT datasets by scanning the reference arm while recording interferometric signals from the sample. Typical acquisition parameters: 512 × 512 A-scans per volume, with scan depth adjusted to encompass the full sample thickness.

SHG Data Acquisition: Following OCT acquisition, switch to SHG imaging mode without moving the sample. Using the femtosecond laser, acquire SHG images by detecting emitted light at exactly half the excitation wavelength (400 nm for 800 nm excitation). Collagen-rich structures will generate strong SHG signals.

Multi-Modal Data Registration: Use fiduciary markers or intrinsic tissue features to precisely align OCT and SHG datasets. Apply appropriate transformation matrices to ensure pixel-level correspondence between modalities.

Image Analysis and Interpretation:

- Segment OCT images to identify tissue layers and structural boundaries

- Quantify SHG signal intensity and distribution to assess collagen density and organization

- Correlate structural features from OCT with molecular information from SHG

- Generate composite visualization that overlays SHG data on OCT structural maps

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Poor SHG signal may indicate suboptimal laser alignment or insufficient collagen content

- Motion artifacts in in vivo OCT can be mitigated by faster scanning or respiratory gating

- Incomplete registration between modalities may require additional control points or landmark-based alignment

Multi-Modal Bioimaging Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Bioimaging

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Bioimaging

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) | Labeling specific cellular structures or proteins | Live-cell tracking, protein localization studies |

| Synthetic Fluorophores (e.g., Alexa Fluor, Cy dyes) | High-intensity labeling with broad spectral range | Multi-color imaging, super-resolution microscopy |

| Quantum Dots | Photostable nanoparticles for long-term imaging | Single-particle tracking, multiplexed detection |

| Environment-Sensitive Dyes | Report on local physicochemical conditions | pH sensing, membrane potential measurements |

| Tissue Clearing Reagents | Render tissues transparent for deep imaging | Light-sheet microscopy, whole-organ imaging |

| Nonlinear Optical Crystals | Frequency conversion for harmonic generation | Calibration standards for SHG/THG microscopy |

Biosensing Systems and Applications

Biosensor Fundamentals and Classification

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological sensing element with a transducer to detect specific analytes, ranging from small molecules to macromolecular complexes [17]. These systems function by integrating a sensor module that detects intracellular or environmental signals with an actuator module that drives a measurable or functional response [17]. The global biosensors market is projected to grow from USD 34.51 billion in 2025 to USD 54.37 billion by 2030, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.5%, reflecting their expanding applications across healthcare, environmental monitoring, and industrial biotechnology [18].

Biosensors are characterized by several key performance metrics: (1) dynamic range, representing the span between minimal and maximal detectable signals; (2) operating range, defining the concentration window for optimal performance; (3) response time, indicating the speed of reaction to analyte changes; and (4) signal-to-noise ratio, determining the clarity and reliability of the output signal [17]. These parameters collectively determine the suitability of biosensors for specific applications, from real-time metabolic monitoring to high-throughput screening in industrial biotechnology.

Biosensors are broadly categorized into wearable and non-wearable formats, with wearable biosensors emerging as the most commercially successful segment [18]. These include sensor patches and embedded devices integrated into larger medical or wearable hardware systems such as smartwatches, fitness bands, ECG patches, and implantable monitors [18]. Wearable biosensors are particularly valuable for continuous, multi-parametric health monitoring and chronic disease management, with form factors ranging from wristwear to bodywear including adhesive patches, smart garments, and headbands [18].

Table 3: Biosensing Technologies by Detection Mechanism

| Biosensor Category | Sensing Principle | Response Characteristics | Advantages | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Measures electrical changes from biochemical reactions | High sensitivity, moderate response time | Low cost, portability, ease of miniaturization | Glucose monitoring, pathogen detection |

| Optical | Detects changes in light properties | High sensitivity, multiplexing capability | Superior sensitivity, non-invasive detection | Oncology, infectious disease detection |

| Piezoelectric | Measures mass/pressure changes on crystal surface | Label-free detection, high mass sensitivity | Detects minute physical interactions | Environmental sensing, gas detection |

| Thermal | Detects temperature changes from reactions | Specialized response profiles | Specific to thermal signatures | Specialized lab analytics |

| Nanomechanical | Uses cantilever sensors at nanoscale | Extreme sensitivity to molecular interactions | Single-molecule detection potential | Early disease detection, personalized medicine |

Experimental Protocol: Developing Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

Objective: To engineer a transcription factor (TF)-based whole-cell biosensor for quantitative monitoring of bioactive compounds in microbial systems.

Materials and Equipment:

- Microbial chassis (e.g., E. coli, Pseudomonas putida)

- Plasmid vectors with modular cloning sites

- Target transcription factor (e.g., TtgR from P. putida)

- Reporter gene (e.g., egfp, mCherry)

- Microplate reader with fluorescence detection capability

- Flow cytometer for single-cell analysis

- Target analyte compounds for testing

- Cell culture equipment and media

Procedure:

- Genetic Construct Design:

- Clone the transcription factor gene (e.g., ttgR) under a constitutive promoter

- Place the reporter gene (egfp) under control of the TF-regulated promoter (e.g., PttgABC)

- Include appropriate selection markers and origins of replication

Biosensor Assembly and Transformation:

- Assemble genetic constructs using standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., Gibson assembly, Golden Gate cloning)

- Transform constructs into appropriate microbial host

- Verify correct assembly by colony PCR and sequencing

Biosensor Characterization:

- Culture biosensor strains in appropriate media to mid-log phase

- Expose to a concentration gradient of target analyte (e.g., 0 μM to 1000 μM)

- Incubate for predetermined time (typically 4-8 hours)

- Measure fluorescence output using plate reader or flow cytometer

- Normalize fluorescence to cell density (OD600)

Dose-Response Analysis:

- Plot fluorescence intensity against analyte concentration

- Fit data to appropriate model (e.g., Hill equation) to determine dynamic range, sensitivity, and EC50

- Calculate response threshold (lowest detectable concentration) and saturation point

Specificity and Cross-Reactivity Testing:

- Expose biosensor to structural analogs of target compound

- Assess response to identify potential cross-reactivities

- For non-responders, consider engineering TF binding pocket for improved specificity

Performance Optimization:

- Fine-tune expression levels by modifying promoter strength, ribosome binding sites, or plasmid copy number

- Address trade-offs between dynamic range and response threshold as needed

- Implement directed evolution strategies if necessary to enhance sensitivity or specificity

Applications in Metabolic Engineering:

- Dynamic regulation of synthetic metabolic pathways

- High-throughput screening of strain libraries

- Real-time monitoring of metabolite production in bioreactors

Transcription Factor Biosensor Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensing

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | Natural sensing elements for specific metabolites | Metabolite biosensors, regulatory circuits |

| Riboswitches | RNA-based sensing elements | Real-time metabolic regulation, compound detection |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins | Generate measurable optical signals | Quantitative biosensor output measurement |

| Toehold Switches | Programmable RNA sensors | Nucleic acid detection, logic-gated control |

| Two-Component Systems | Signal transduction from extracellular cues | Environmental sensing, intercellular communication |

| Enzyme-Based Sensors | Catalytic detection of specific substrates | Specific molecular detection with signal amplification |

Photonic Therapies and Treatment Modalities

Principles of Light-Based Therapies

Photonic therapies encompass a range of light-based treatment modalities that leverage the interactions between light and biological tissues for therapeutic purposes [10]. These approaches include laser surgery, photodynamic therapy, low-level light therapy, and photobiomodulation, each with distinct mechanisms of action and clinical applications [10]. The fundamental principle underlying photonic therapies is the selective absorption of light by specific tissue components or photosensitizing agents, leading to localized therapeutic effects while minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues.

Lasers and other advanced light sources enable highly precise and minimally invasive surgical interventions, with applications ranging from ophthalmology and dermatology to oncology and neurosurgery [10]. The efficacy of these treatments is often monitored in real-time using complementary bioimaging and biosensing modalities, creating integrated therapeutic platforms that combine diagnosis and treatment in a single workflow [10]. Recent advances in photonic therapies include the development of targeted approaches that respond to specific molecular biomarkers, enabling personalized treatment strategies with improved therapeutic outcomes and reduced side effects.

Experimental Protocol: Fluorescence-Guided Surgery with Nanobodies

Objective: To implement fluorescence-guided surgery using targeted nanobodies and fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) for enhanced tumor specificity and reduced background signal.

Materials and Equipment:

- Targeted nanobody-fluorophore conjugates (e.g., anti-EGFR nanobody with IRDye 800CW)

- Surgical microscope with fluorescence imaging capability

- Fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) system

- Animal model with appropriate tumor xenografts

- Anesthesia equipment and monitoring systems

- Image processing software with FLIM analysis capabilities

Procedure:

- Probe Preparation and Characterization:

- Conjugate selected nanobodies with appropriate fluorophores

- Purify conjugates using size exclusion chromatography

- Characterize labeling efficiency and binding specificity using flow cytometry or ELISA

- Determine optimal imaging time window through pharmacokinetic studies

Preoperative Planning:

- Establish baseline imaging of surgical area using white light and fluorescence

- Identify potential areas of concern based on preoperative imaging

- Determine surgical approach that maximizes visualization of fluorescent signals

Administration of Targeted Agent:

- Administer nanobody-fluorophore conjugate via appropriate route (typically intravenous)

- Allow sufficient time for agent distribution and target binding (typically 2-48 hours depending on agent)

- Clear unbound agent from circulation to reduce background signal

Intraoperative Imaging and FLIM:

- Perform surgery under standard white light illumination

- Switch to fluorescence mode to identify target-positive tissues

- Acquire FLIM data to distinguish specific binding from non-specific signal based on fluorescence lifetime differences

- Use real-time image overlay to guide surgical margins and identify potential metastatic deposits

Tissue Validation:

- Collect excised tissues for histopathological analysis

- Correlate fluorescence signals with histological findings

- Assess margin status using both conventional pathology and fluorescence imaging

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Quantify fluorescence intensity in target versus non-target tissues

- Analyze fluorescence lifetime distributions to differentiate specific from non-specific binding

- Calculate target-to-background ratios for quantitative assessment of imaging performance

Advantages of Nanobody-Based Approaches:

- Rapid pharmacokinetics leading to higher target-to-background ratios

- Superior tissue penetration compared to full antibodies

- Potential for same-day imaging and surgery

- Reduced immunogenicity

Fluorescence-Guided Surgical Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Photonic Therapies

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Photonic Therapies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Photosensitizers | Light-activated compounds for therapy | Photodynamic therapy, antimicrobial applications |

| Targeted Nanobodies | Small antigen-binding domains for precision targeting | Fluorescence-guided surgery, molecular imaging |

| Biocompatible Fluorophores | Light-emitting molecules for visualization | Surgical guidance, treatment monitoring |

| Light-Activated Ion Channels | Optogenetic control of cellular activity | Neuromodulation, cardiac pacing |

| Thermoplastic Polymers | Materials for light-based fabrication | Medical device manufacturing, surgical guides |

| Light-Activated Drugs | Therapeutic compounds with photolabile protecting groups | Spatiotemporally controlled drug release |

Integrated Systems and Future Directions

Convergence of Bioimaging, Biosensing, and Therapies

The most significant advances in bio-optics are emerging from integrated systems that combine bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic therapies into unified platforms [10]. These integrated approaches enable closed-loop systems where sensing informs treatment, and imaging guides intervention, creating responsive therapeutic systems with unprecedented precision. For example, intraoperative imaging systems can now combine multiple modalities like OCT, fluorescence imaging, and photoacoustic imaging to provide comprehensive tissue characterization during surgical procedures, while integrated biosensors monitor physiological parameters in real-time to guide therapeutic decisions [10].

The convergence of these technologies is particularly evident in emerging applications such as theranostics (combined therapy and diagnostics), where a single agent serves both diagnostic and therapeutic functions [10]. Photoactivatable agents, for instance, can be visualized using fluorescence imaging to confirm target engagement before light activation initiates therapeutic action. This approach minimizes off-target effects and enables personalized treatment dosing based on real-time assessment of drug distribution and target expression [10].

Enabling Technologies and Future Outlook

Several enabling technologies are driving the future integration of bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic therapies. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are playing an increasingly transformative role by enhancing data analysis, interpretation, and optimization of complex imaging and sensing data [4] [10]. These computational approaches enable real-time decision support, automated image interpretation, and optimization of optical systems for specific applications [4].

Novel materials, including nanomaterials, metamaterials, and stimuli-responsive polymers, are expanding the capabilities of bio-optical systems through enhanced contrast, improved targeting, and responsive functionality [10]. Quantum technologies, including quantum sensing and imaging, promise unprecedented sensitivity for detecting biological signals at the fundamental physical limits [10]. These advances are complemented by progress in miniaturization and wearable technologies, making sophisticated bio-optical systems increasingly accessible for point-of-care applications and continuous health monitoring [18].

The future of bio-optics will see increased emphasis on multimodal integration, where complementary technologies are combined to overcome individual limitations and provide more comprehensive biological information [10]. Clinical translation will be accelerated through improved standardization, validation protocols, and regulatory frameworks that ensure the safety and efficacy of these advanced bio-optical systems [10]. As these trends converge, bioimaging, biosensing, and photonic therapies will become increasingly central to precision medicine, enabling personalized approaches to diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment across a wide spectrum of diseases and health conditions.

Core Technologies and Their Transformative Applications in Biomedicine

Optical imaging modalities have revolutionized biomedical research and diagnostic medicine by enabling non-invasive, high-resolution visualization of biological tissues. Among these, Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Multiphoton Microscopy (MPM) represent two powerful technologies that operate on fundamentally different physical principles while offering complementary capabilities. OCT leverages low-coherence interferometry to provide cross-sectional structural information, while MPM utilizes nonlinear optical processes to achieve high-resolution molecular imaging. The integration of these modalities addresses the critical trade-offs between imaging depth, resolution, and molecular specificity that have historically limited individual optical techniques. This technical guide examines the core principles, current advancements, and synergistic applications of OCT and MPM, with particular emphasis on their growing importance in preclinical research and drug development workflows where comprehensive structural and functional assessment is required.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Specifications

Optical Coherence Tomography: Theory and Evolution

OCT operates on the principle of low-coherence interferometry to perform optical sectioning within scattering tissues. The technology measures backscattered light from internal tissue structures by comparing it with light from a reference arm, generating cross-sectional images with micron-scale resolution. The evolution of OCT has progressed through several generations, each offering distinct advantages. Time-Domain OCT (TD-OCT) utilizes a moving reference mirror and was the first commercially available implementation, providing basic imaging capability but limited by slower acquisition speeds (approximately 400 A-scans/second) and lower resolution (8-10 µm axial resolution) [19]. The development of Spectral-Domain OCT (SD-OCT) dramatically improved performance by replacing the moving reference with a stationary spectrometer, enabling significantly faster acquisition rates (20,000-52,000 A-scans/second) and improved axial resolution (5-7 µm) [19]. The current state-of-the-art, Swept-Source OCT (SS-OCT), employs a wavelength-swept laser and photodetector to achieve even faster scanning rates (100,000-236,000 A-scans/second) with enhanced penetration depth, making it particularly suitable for imaging deeper ocular structures and anterior segment visualization [19].

Table 1: Technical Comparison of OCT Modalities

| Parameter | TD-OCT | SD-OCT | SS-OCT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Broadband light source with moving reference mirror | Broadband light with spectrometer detection | Tunable laser swept across wavelengths |

| Axial Resolution | 8-10 µm | 5-7 µm | ~11 µm |

| Scan Rate | 400 A-scans/s | 20,000-52,000 A-scans/s | 100,000-236,000 A-scans/s |

| Key Advantages | Lower cost | High resolution, widely available | Superior depth penetration, faster imaging |

| Primary Limitations | Slow acquisition, motion artifacts | Limited depth penetration | Higher cost, limited availability |

Multiphoton Microscopy: Physical Foundations and Advancements

Multiphoton microscopy encompasses both two-photon and three-photon excitation processes that rely on the near-simultaneous absorption of multiple photons to excite fluorescent molecules. The probability of multiphoton absorption depends on the square (for two-photon) or cube (for three-photon) of the instantaneous light intensity, confining excitation to a small focal volume without the need for a detection pinhole. This inherent optical sectioning capability, combined with the use of longer excitation wavelengths (typically in the near-infrared range), enables deep tissue imaging with reduced phototoxicity compared to confocal microscopy [20]. Two-photon microscopy typically employs excitation wavelengths of 680-1050 nm for imaging conventional fluorophores, while three-photon microscopy utilizes longer wavelengths (1300-1700 nm) to access greater penetration depths in highly scattering tissues like the brain [20].

Recent advancements in MPM have focused on extending imaging depth through optimized wavelength selection. The effective attenuation coefficient in biological tissues reaches a minimum at approximately 1.7 µm, making this wavelength ideal for three-photon excitation of red fluorophores [20]. Additionally, the development of adaptive excitation sources and pulse-on-demand systems has improved signal strength by concentrating illumination only on regions of interest, thereby increasing permissible pulse energy at the focus while maintaining safe average power levels [20]. The integration of adaptive optics has demonstrated approximately 10× signal increase for neuronal imaging and up to 30× enhancement for finer dendritic structures by correcting for tissue-induced aberrations [20].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Multiphoton Modalities

| Parameter | Confocal Microscopy | Two-Photon Microscopy | Three-Photon Microscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Mechanism | Single-photon absorption | Simultaneous two-photon absorption | Simultaneous three-photon absorption |

| Excitation Wavelength | Visible/UV | NIR (680-1050 nm) | Longer NIR (1300-1700 nm) |

| Penetration Depth | Shallow (100-200 µm) | Moderate (500-800 µm) | Deep (up to 1.5 mm) |

| Resolution | High (lateral: 0.2 µm, axial: 0.5 µm) | Slightly lower than confocal | Similar to two-photon |

| Background Signal | High without pinhole | Minimal, inherent sectioning | Minimal, improved sectioning |

| Photodamage | High in deep tissue | Reduced outside focal plane | Further reduced outside focus |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Integrated OCT-MPM System for Cochlear Imaging

A representative multimodal imaging platform combines spectral-domain OCT with two-photon microscopy for investigating mechanotransduction in the mammalian cochlea. This system addresses the challenge of rapid switching between optical configurations with different numerical apertures (ranging from 0.13 to 0.8) required to capture both cellular (<10 µm) and structural (>200 µm) details [21].

System Configuration:

- Light Sources: The integrated system incorporates a custom SD-OCT engine alongside a femtosecond laser for two-photon excitation.

- Beam Conditioning: Two tunable liquid lenses form a beam expander that dynamically adjusts beam diameter at the back aperture of each objective, optimizing light throughput and maintaining high signal-to-noise ratio across all objectives [21].

- Automation: Optical adjustments are automated to facilitate seamless imaging across spatial scales, enabling high-precision vibration and fluorescence imaging in a single experimental session.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Excised murine cochlea samples or living murine models are positioned using a high-precision stage.

- Multimodal Data Acquisition:

- TPM is first used to locate fluorescent outer hair cells through the round window membrane.

- OCT vibrometry measurements are performed concurrently to assess tissue mechanics.

- Functional Assessment: Cochlear structures including hair cells, basilar membrane, and reticular lamina are analyzed for phase relationships in response to acoustic stimuli (e.g., 70 kHz at 90 dB SPL) [21].

Key Findings: The integrated system demonstrated that all measured cochlear structures moved in phase in response to high-frequency stimulation, consistent with expected cochlear mechanics [21].

Combined MPM/OCT for Refractive Index and Thickness Characterization

This methodology enables noninvasive characterization of refractive index (RI) and thickness distribution in biological tissues through the synergistic combination of multiphoton microscopy and OCT.

Theoretical Basis: OCT measures optical pathlength (Lp), which represents the product of physical thickness (t) and refractive index (n): Lp = t × n [22]. Multimodal imaging resolves this ambiguity by providing independent measurements of optical pathlength (from OCT) and physical thickness (from MPM), allowing calculation of RI as n = Lp/t.

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Fresh tissue samples (e.g., fish cornea) are mounted without chemical fixation or sectioning.

- Co-registered Imaging:

- OCT cross-sectional images are acquired to determine optical pathlength.

- 3D MPM images (TPEF and SHG) are successively captured at the identical sample location to determine physical thickness.

- Data Analysis:

- Tissue layers are distinguished based on biochemical contrasts from MPM (cellular features via TPEF, collagen via SHG).

- For each identified layer, physical thickness is derived from MPM data while optical pathlength is obtained from OCT.

- Layer-specific RI is calculated as the ratio of optical pathlength to physical thickness.

Validation: The method demonstrated precision within ~1% error compared to reference values when tested on standard samples (water, air, immersion oil, cover glass) [22]. Application to fish cornea identified three distinct layers with RIs of ~1.446-1.448 (epithelium), 1.345-1.372 (stroma I), and 1.392-1.436 (stroma II), correlating with their tissue compositions [22].

Integrated Optoacoustic and Two-Photon Microscopy for Neuroimaging

This protocol details the integration of optical-resolution optoacoustic microscopy (OAM) with two-photon microscopy for functional neuroimaging in murine models, enabling comprehensive analysis of neurovascular coupling.

System Configuration:

- Light Sources: Separate nanosecond and femtosecond laser sources for OAM and TPM, respectively.

- Data Acquisition: Custom LabVIEW code manages semi-simultaneous acquisition, capturing alternating frames from OAM and TPM subsystems at different time points [23].

- Spatial Resolution: The TPM subsystem achieves 400 nm lateral and 6.85 µm axial resolution, while OAM achieves 670 nm lateral and 4.01 µm axial resolution [23].

Experimental Protocol:

- Animal Preparation:

- C57BL/6 mice are injected with adeno-associated virus (AAV) for neuronal labeling.

- A 3-mm diameter cranial window is created over the primary somatosensory cortex.

- A head plate is attached to the skull using cyanoacrylate glue and dental cement.

- In Vivo Imaging:

- Mice are anesthetized with ketamine (25 mg/kg) and xylazine (1.25 mg/kg).

- Physiological parameters (body temperature, oxygen saturation) are continuously monitored.

- Medical ultrasonic gel is applied to ensure efficient coupling of ultrasound waves.

- Data Acquisition:

- Z-stacks (330 × 300 µm² FOV) up to 350 µm depth are acquired semi-simultaneously.

- Vascular networks are imaged at 90 µm depth across an 800 × 800 µm² lateral FOV with OAM.

- Neuronal structures are captured concurrently via TPM at matching depth planes.

Functional Analysis: The system captures spontaneous vasodilation and vasoconstriction dynamics in cortical vessels, with diameter changes monitored over time to investigate neurovascular coupling mechanisms [23].

Advanced Applications and Current Research

Ophthalmic Imaging and Accessibility Innovations

OCT has established itself as the clinical standard for retinal disease diagnosis and management, with recent innovations focusing on improving accessibility. Traditional OCT systems require trained technicians and are confined to clinical settings, creating barriers for elderly, rural, and frequently monitored patients [19]. The development of portable, community-based systems like the SightSync OCT addresses these limitations through a compact design (6 × 6 mm resolution, 80,000 A-scans/s) that enables technician-free operation with secure data transfer capabilities [19]. This innovation expands screening possibilities for vision-threatening conditions like age-related macular degeneration (affecting approximately 196 million people globally in 2020) and diabetic retinopathy (affecting 103.12 million adults worldwide) [19].

Multimodal platforms such as the Silverstone system integrate RGB imaging with OCT, fluorescein angiography, indocyanine green angiography, and autofluorescence. The addition of blue wavelength in RGB imaging provides enhanced visualization of whitish features like fibrosis and inflammation, while peripheral OCT capability enables examination of previously inaccessible retinal lesions [24]. These integrated systems eliminate the need to move patients between different imaging devices, significantly improving clinical workflow efficiency.

Deep Tissue and In Vivo Functional Imaging