Bio-Optical Sensors for Water Quality Monitoring: Advanced Technologies and Biomedical Applications

This article explores the transformative role of bio-optical sensors in water quality monitoring, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical research and drug development.

Bio-Optical Sensors for Water Quality Monitoring: Advanced Technologies and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of bio-optical sensors in water quality monitoring, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical research and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of optical biosensing technologies—including fluorescence, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and fiber-optic sensors—and their specific applications in detecting waterborne pathogens, emerging contaminants, and pharmaceutical residues. The content provides a critical analysis of current performance metrics, addresses key challenges in real-world deployment such as biofouling and calibration, and offers a comparative evaluation of sensing methodologies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent technological advances to highlight how improved water monitoring directly supports public health initiatives, antimicrobial resistance studies, and ensures water quality in biomedical manufacturing.

Principles and Evolution of Bio-Optical Sensing Technologies

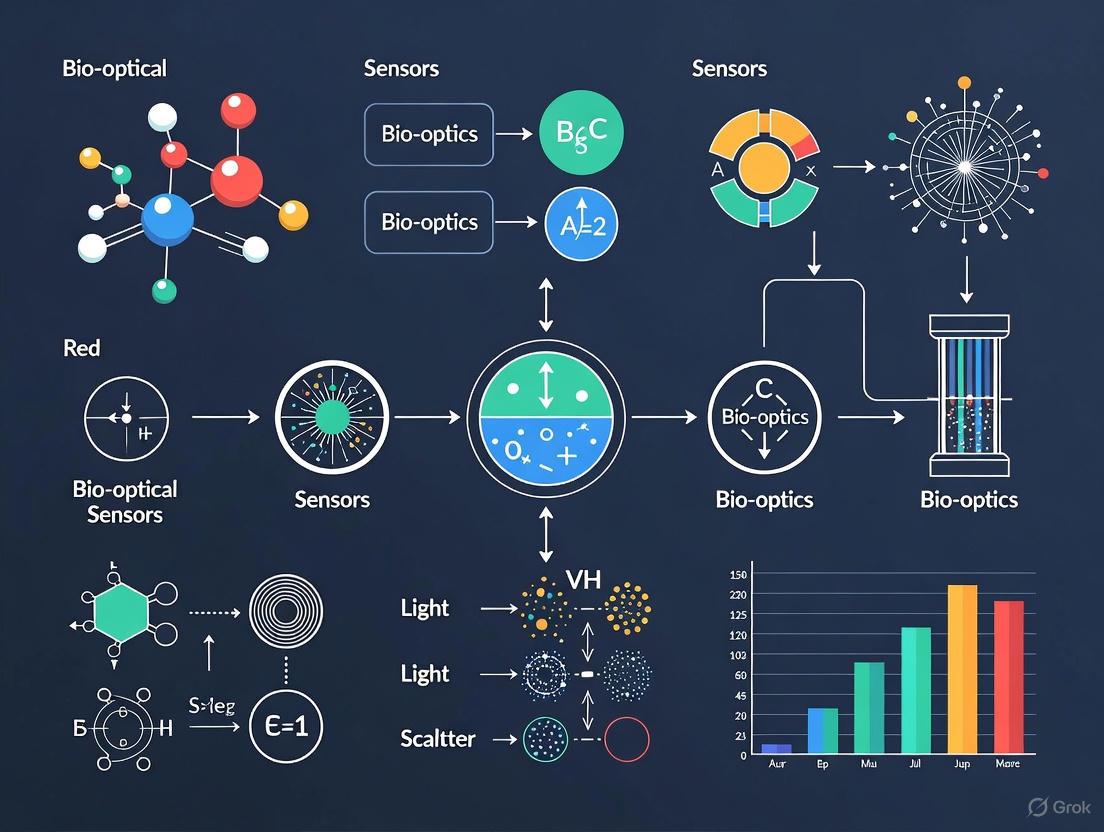

Bio-optical sensors represent a transformative approach in analytical science, leveraging the interactions between light and matter to detect and quantify biological and chemical substances. Within the specific application of water quality monitoring, these sensors provide the rapid, sensitive, and real-time analysis essential for safeguarding water resources. The core optical principles of fluorescence, absorbance, and light scattering form the foundation of many advanced biosensing platforms. Their integration into sensor design enables the detection of a wide range of water quality parameters, from chemical contaminants and nutrient levels to biological agents, with minimal sample preparation and without generating secondary pollutants [1] [2]. This document details the fundamental operating principles, experimental protocols, and key reagents associated with these techniques, framed within the context of developing robust bio-optical sensors for water quality research.

Theoretical Foundations

Fluorescence

The principle of fluorescence involves the emission of light from a substance that has absorbed photons of a higher energy (shorter wavelength). A photon excites a fluorophore's electron to a higher energy state; upon returning to its ground state, a photon is emitted at a longer wavelength. The difference between the excitation and emission wavelengths is known as the Stokes shift [3].

The efficiency of this process is quantified by the quantum yield, which is the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed. A high quantum yield is critical for sensitive detection. In sensing, the target analyte can directly influence the fluorophore's intensity, lifetime, or spectral position. Common transduction mechanisms include photobleaching (irreversible loss of fluorescence) and Förster Resonance Energy Transfer, a non-radiative energy transfer between two light-sensitive molecules that is highly dependent on their proximity, enabling the sensing of molecular binding events [3].

Absorbance

Absorbance spectroscopy measures the attenuation of a light beam as it passes through a sample. Molecules absorb photons of specific wavelengths, exciting their electrons. The extent of absorption is quantitatively described by the Beer-Lambert Law: [ A = \epsilon l c ] where ( A ) is the measured absorbance, ( \epsilon ) is the molar absorptivity, ( l ) is the optical path length, and ( c ) is the analyte concentration [3] [4].

This relationship allows for the direct quantification of analyte concentration. In water quality monitoring, absorbance measurements in various spectral ranges can identify and quantify specific pollutants, such as nitrates or organic matter, based on their unique absorption fingerprints [1] [5].

Light Scattering

Light scattering encompasses phenomena where light is redirected by particles or molecules in a medium. For particles much smaller than the light's wavelength, Rayleigh scattering occurs, where the scattering intensity is proportional to the sixth power of the particle diameter and the fourth power of the light frequency [6].

Static Light Scattering can be used to determine the size and concentration of particles in suspension. When combined with machine learning algorithms, it provides a high-throughput method for analyzing parameters like microplastic concentration in water samples [7]. Interference-based detection is a highly sensitive derivative of scattering where the weak scattered light from a small particle interferes with a reference light wave. The resulting interference pattern provides a powerful signal for detecting nanoparticles and even single biomolecules, functioning as an optical analog of mass spectrometry [6].

Experimental Protocols & Applications in Water Quality

Protocol 1: Heavy Metal Detection using a Fluorescence-Based Fiber Optic Sensor

This protocol details the detection of mercury ions in water using a quantum dot-based fiber optic fluorescence sensor [2] [4].

- Principle: Mercury ions quench the fluorescence of quantum dots immobilized on an optical fiber. The degree of fluorescence quenching is proportional to the concentration of Hg²⁺.

- Key Reagents & Materials: See Table 1 in the "Research Reagent Solutions" section.

- Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: Taper a multimode optical fiber to create an evanescent wave sensing region. Immerse the tapered region in a solution containing functionalized quantum dots to allow for surface immobilization.

- System Setup: Connect the proximal end of the fiber to a laser source and the distal end to a spectrometer via an optical filter to block the excitation wavelength.

- Calibration: Immerse the sensor probe in a series of standard Hg²⁺ solutions with known concentrations. Measure the fluorescence intensity at 670 nm after a 3-minute exposure for each standard.

- Sample Measurement: Immerse the sensor probe in the untreated water sample for 3 minutes. Record the fluorescence intensity.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Hg²⁺ concentration in the sample by comparing the fluorescence intensity to the calibration curve. The reported limit of detection for this method is 1 nM [4].

Diagram: Workflow for Fluorescence-Based Mercury Detection.

Protocol 2: Turbidity and Total Suspended Solids (TSS) via Light Scattering

This protocol describes a method for determining microplastic size and concentration using Static Light Scattering enhanced with machine learning [7].

- Principle: Particles in suspension scatter incident light. The angular distribution and intensity of the scattered light are functions of the particle size, shape, and concentration.

- Key Reagents & Materials:

- Standard polystyrene microplastic suspensions (0.5 - 20 µm).

- SLS instrument with a laser source and multi-angle detectors.

- Computer with machine learning algorithms for data processing.

- Procedure:

- System Calibration: Use a series of monodisperse polystyrene microsphere standards of known size and concentration to calibrate the SLS instrument.

- Data Collection: Introduce the water sample into the flow cell. Illuminate with a laser and collect scattering intensity data at multiple angles.

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model using the scattering data from known standards to recognize the patterns associated with specific sizes and concentrations.

- Sample Analysis: Pass the scattering data from an unknown sample through the trained model to determine the size distribution and concentration of suspended particles.

- Validation: Validate the method by comparing results with established techniques, such as filtration and microscopy.

Protocol 3: Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) Estimation via UV-Vis Absorbance

This protocol uses ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy to estimate COD, a key indicator of organic pollution in water.

- Principle: Organic matter in water absorbs UV light, particularly at wavelengths around 254 nm. This absorbance has been correlated with traditional COD measurements, providing a rapid, non-chemical alternative.

- Key Reagents & Materials:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with a quartz cuvette.

- Potassium hydrogen phthalate for standard preparation.

- Procedure:

- Standard Curve Generation: Prepare COD standard solutions using potassium hydrogen phthalate. Measure the absorbance of each standard at 254 nm using the spectrophotometer.

- Sample Measurement: Filter the water sample to remove large particulates. Measure its absorbance at 254 nm.

- Calculation: Determine the sample's COD value by interpolating its absorbance from the standard curve.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key reagents and materials for bio-optical sensing in water quality applications.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Dots | Nanoscale semiconductor particles with high quantum yield and tunable emission; serve as fluorescent probes. | Detection of heavy metal ions via fluorescence quenching [4]. |

| Concanavalin A (ConA) | A lectin protein that reversibly binds glucose and mannose; used in competitive binding assays. | Fluorescent glucose biosensing for organic pollution tracking [2]. |

| Isoxazolidine (IXZD) | A molecular probe embedded in a polymer film; acts as a "turn-on" optical chemosensor. | Selective detection of mercury ions and pH in water samples [2]. |

| Citizen Science Test Kits | Affordable, portable kits for measuring parameters like pH, ammonia, and nitrate. | Enabling broad-scale, contributory water quality data collection [8]. |

| Ormosil Nanoparticles | Organically modified silica nanoparticles used as a matrix for hosting multiple sensing probes. | Simultaneous sensing of pH and dissolved oxygen [2]. |

| Functionalized Nanomaterials | Low-dimensional nanomaterials enhance sensitivity via plasmonic or fluorescent effects. | Core component in advanced optical biosensors for trace contaminant detection [9]. |

Table 2: Performance comparison of optical sensing techniques for water quality monitoring.

| Detection Principle | Target Analyte | Limit of Detection (LOD) / Sensitivity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence | Hg²⁺ Ions | 1 nM [4] | High sensitivity, suitability for remote sensing via optical fibers. |

| Fluorescence | Biothiols (Cys, Hcy, GSH) | 0.02 μM, 0.42 μM, 0.92 μM respectively [2] | Capable of differential detection of similar compounds. |

| Interferometric Scattering | Single Proteins | Demonstrated for proteins in the tens of kilodalton range [6] | Label-free, quantitative mass measurement at the single-molecule level. |

| SERS | Ethanol/Methanol in spirits | Below legal thresholds [2] | Provides molecular "fingerprint"; resistant to water interference. |

| Absorbance | General Organic Matter | Correlation with COD [1] | Rapid, no chemical reagents required, easy to implement. |

| Static Light Scattering | Microplastics (0.5-20 µm) | High-throughput size and concentration analysis [7] | Can be combined with ML for automated analysis. |

The principles of fluorescence, absorbance, and light scattering provide a versatile and powerful toolkit for addressing the complex challenges of modern water quality monitoring. The experimental protocols and data outlined herein demonstrate the potential of these bio-optical sensing strategies to achieve high sensitivity, specificity, and real-time capability. Future trends are focused on the integration of these optical modalities with low-dimensional nanomaterials and artificial intelligence to develop feasible, miniaturized, and commercially viable biosensor systems for comprehensive water security [9] [1] [5].

Bio-optical sensors represent a transformative technological advancement for environmental monitoring, combining biological recognition elements with optical transduction mechanisms to detect water contaminants with high specificity and sensitivity. These devices are particularly valuable for detecting emerging contaminants (ECs) and pathogens in water, addressing critical limitations of traditional analytical methods like chromatography and mass spectrometry, which are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and require sophisticated laboratory equipment [10]. The core principle of a biosensor involves the integration of a bioreceptor, which specifically binds to the target analyte, with a transducer that converts this biological interaction into a quantifiable optical signal [10]. This capability for rapid, sensitive, and selective detection makes biosensors ideal for real-time, on-site water quality assessment, a crucial need for safeguarding public health and aquatic ecosystems [10] [11].

The relevance of these sensors is underscored by the growing global water crisis, intensified by climate change, population growth, and the release of persistent pollutants such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and industrial chemicals into water bodies [10]. In this context, bio-optical sensors offer significant advantages, including minimal sample preparation, short measurement times, high specificity and sensitivity, and the potential for low detection limits [11]. This article provides a detailed examination of three principal types of bio-optical sensors—Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Fiber-Optic, and Photonic Crystal Biosensors—framed within the practical requirements of water quality research. It includes structured performance comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and essential resource guides to facilitate their application in cutting-edge environmental monitoring research.

Operating Principles and Performance Comparison

Fundamental Sensing Mechanisms

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensors: SPR is a label-free optical phenomenon that occurs at a metal-dielectric interface [12]. When polarized light strikes a thin metal film (such as gold) under conditions of total internal reflection, it excites surface plasmons—collective oscillations of free electrons. This excitation leads to a characteristic dip in the reflected light intensity at a specific resonance angle or wavelength. Any change in the refractive index near the metal surface, such as that caused by the binding of a target analyte (e.g., a pollutant) to a bioreceptor immobilized on the surface, shifts the resonance condition. This shift provides a highly sensitive, real-time measurement of the binding event [12]. The integration of SPR with photonic crystal fibers (PCFs) has opened new avenues for highly sensitive, miniaturized biosensing platforms [12].

Fiber-Optic Biosensors: These sensors use optical fibers as the transduction platform, guiding light to and from a sensing region. The biological recognition element is immobilized on or near the fiber. An interaction with the target analyte modulates the light's properties (e.g., intensity, wavelength, phase, or polarization) [13]. A prominent subtype is the whole-cell fiber-optic biosensor, where genetically engineered microorganisms (bioreporters) are immobilized on the fiber tip. These bioreporters produce a quantifiable signal, such as bioluminescence, in response to specific toxicants or environmental stressors, enabling effect-based toxicity assessment of water and sediments [13].

Photonic Crystal (PC) Biosensors: Photonic crystals are materials with a periodic dielectric structure that creates a photonic bandgap, preventing the propagation of specific wavelengths of light [12]. Photonic crystal fibers (PCFs) are a specialized class of optical fibers featuring a microstructured arrangement of air holes running along their length [12] [14]. This structure offers exceptional control over light propagation. When the air holes of a PCF are infiltrated with an analyte, the change in the effective refractive index alters the fiber's transmission properties. This allows for the detection of specific chemical and biological molecules, as many exhibit distinct spectral 'fingerprints' in ranges like the terahertz (THz) band [14]. PCF sensors can be engineered for ultra-high sensitivity and negligible confinement loss by optimizing the geometry of the air holes and the core design [14].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below summarizes key performance metrics and applications of the three bio-optical sensor types in water quality monitoring, synthesized from recent research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Bio-Optical Sensors for Water Quality Monitoring

| Sensor Type | Key Performance Metrics | Target Analytes in Water | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR Biosensors | High sensitivity; Real-time, label-free detection [12]. | Biomolecules, chemicals, bacterial cells (e.g., E. coli, cancer cells, DNA, proteins, excess cholesterol) [12]. | Exceptional sensitivity; Suitable for biomolecular interaction studies; Can be integrated with PCFs [12]. | Can require complex setup; Sensor surface may be prone to fouling [12]. |

| Fiber-Optic Biosensors | Rapid response (minutes); High sensitivity to general toxicity [13]. | General cytotoxicity, genotoxicants, heavy metals, organic pollutants [13]. | Effect-based measurement; On-site, direct sediment/water toxicity assessment; Portable field kits [13]. | Bioreporter requires culturing and maintenance; Signal stability over long deployments [13]. |

| Photonic Crystal Biosensors | Ultra-high relative sensitivity (e.g., >96%), extremely low confinement loss (e.g., 10⁻¹¹ dB/m) [14]. | Chemical pollutants, aquatic pathogens (e.g., Vibrio cholerae, E. coli), refractive index changes [14]. | Ultra-high sensitivity and low loss; Design flexibility; Can be used for THz fingerprinting [14]. | Complex fiber fabrication; Can be sensitive to multiple environmental parameters [15]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Development of a Whole-Cell Fiber-Optic Biosensor

This protocol details the construction and use of a biosensor for direct, on-site assessment of bioavailable toxicity in water and sediment samples, based on the work described by [13].

Principle: Genetically modified E. coli bacteria, bearing a bioluminescence reporter gene fusion (e.g., the grpE promoter from the heat shock regulon fused to the luxCDABE operon), are immobilized on an optical fiber tip. Upon exposure to cytotoxic stressors in the sample, the bacteria produce a dose-dependent bioluminescent response, which is captured by the optical fiber connected to a photon-counting device [13].

Diagram 1: Whole-cell biosensor workflow.

Materials:

- Bioreporter Strain: E. coli TV1061 (or other relevant stress-responsive strain) [13].

- Optical Fibers: Multimode optical fibers with polished ends.

- Immobilization Matrix: Sodium alginate (low viscosity), Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) solution.

- Culture Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and LB agar, with appropriate antibiotics.

- Equipment: BenchTop orbital shaker incubator, centrifuge, spectrophotometer, photon counter/light measurement system embedded in a portable, light-proof case [13].

Procedure:

- Cell Culturing and Preparation:

- Inoculate E. coli TV1061 from a glycerol stock or a fresh colony into LB broth supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., 100 µg/mL ampicillin). Incubate at 37°C with shaking at 220 RPM for 24 hours.

- Prepare a secondary culture by diluting the primary culture 1:50 into fresh, antibiotic-free LB medium. Incubate at 37°C with shaking until the optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) reaches 0.6–0.8 (mid-exponential phase) [13].

- Centrifuge the bacterial suspension at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in the remaining small volume (~5 mL) to achieve a concentrated cell suspension with an OD₆₀₀ of approximately 1.2–1.4 [13].

Fiber Tip Functionalization and Cell Immobilization:

- Mix the concentrated bacterial suspension thoroughly with a sterile, low-viscosity sodium alginate solution to form a homogeneous cell-alginate mixture.

- Carefully dip the tip of the optical fiber into this mixture to coat it.

- Subsequently, dip the coated fiber tip into a 0.1 M CaCl₂ solution for several minutes to cross-link the alginate, forming a stable hydrogel matrix that entraps the bacteria. The hydrogel acts as a semi-permeable membrane, allowing toxicants to diffuse in while retaining the cells [13].

- Gently rinse the functionalized fiber tip with a buffer solution to remove excess CaCl₂ and non-immobilized cells.

Toxicity Measurement and Signal Acquisition:

- For on-site measurement, directly submerge the functionalized fiber tip into a vial containing the water or sediment sample.

- For lab-based analysis, the sample can be extracted first, and the fiber tip submerged in the extract.

- Connect the proximal end of the optical fiber to a photon counter (e.g., a photomultiplier tube module) housed within a light-proof portable case.

- Acquire the bioluminescence signal over a predetermined exposure time (e.g., 5-15 minutes). The light intensity, measured in relative light units (RLU), is proportional to the level of cellular stress induced by the bioavailable toxicants in the sample [13].

Protocol: PCF-SPR Sensor for Specific Pollutant Detection

This protocol outlines the design and numerical analysis of a photonic crystal fiber sensor based on surface plasmon resonance for identifying water pollutants, leveraging advanced computational modeling.

Principle: A PCF is designed with a specific microstructure (e.g., a hybrid cladding with rectangular and elliptical air holes) to guide light efficiently. A plasmonic material (e.g., gold) is deposited on selected surfaces or channels within the fiber. When the fiber's core or channels are infiltrated with an analyte (e.g., polluted water), the change in the refractive index alters the phase-matching condition between the core mode and the surface plasmon polariton mode, leading to a shift in the loss spectrum's resonance wavelength [12] [14].

Diagram 2: PCF-SPR sensor analysis.

Materials (for Simulation):

- Software: COMSOL Multiphysics with Wave Optics Module, or similar Finite Element Method (FEM) software [14] [15].

- Material Libraries: Optical properties of Zeonex (a common PCF substrate), silica, gold, and other plasmonic materials.

- Analytes: Refractive index data for pure water (≈1.33) and target polluted water with specific contaminants (refractive index can range to ~1.46) [14].

Procedure (Computational Analysis):

- Sensor Geometry Definition:

- Using the simulation software, create a 2D cross-sectional model of the PCF. A typical design might include a rectangular core for analyte infiltration, surrounded by a unique hybrid cladding with inner "mode-shaping" rectangular air holes and an outer "confinement" ring of elliptical air holes [14].

- Define the geometric parameters: pitch (Λ), air-hole diameters, core dimensions, and the thickness of any plasmonic metal layers (e.g., 40 nm gold) [14] [15].

Material Assignment and Meshing:

- Assign the correct material properties to each domain: Zeonex (n≈1.53) for the background, air (n=1) for the holes, and the complex refractive index for gold (from material libraries) [14].

- Define the analyte by setting the refractive index of the core region to that of the target sample (e.g., 1.33 for pure water, 1.41 for polluted water) [14].

- Generate a sufficiently fine mesh, particularly at the metal-dielectric interfaces, to ensure computational accuracy.

Mode Analysis and Loss Calculation:

- Set the operating frequency range (e.g., 0.5 to 3.0 THz) [14].

- Run an eigenfrequency or mode analysis study to find the effective mode index (n_eff) of the fundamental core mode and the surface plasmon polariton (SPP) mode.

- The confinement loss is calculated from the imaginary part of the complex effective mode index using the formula [12] [15]:

Confinement Loss (dB/cm) = 8.686 × (2π / λ) × Im(n_eff) × 10^4

Sensitivity Calculation:

- The relative sensitivity is a key performance metric and is often calculated as [14]:

S = (n_analyte / n_eff) × FWhereFis the fraction of the total power flowing in the analyte-filled region. A well-designed sensor can achieve relative sensitivities exceeding 96% [14]. - To simulate sensing performance, vary the analyte's refractive index in the core and re-run the simulation. The wavelength shift of the confinement loss peak per unit change in refractive index (nm/RIU) quantifies the sensor's sensitivity.

- The relative sensitivity is a key performance metric and is often calculated as [14]:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and deployment of bio-optical sensors require a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table itemizes key components for the featured experimental protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bio-Optical Sensor Development

| Item Name | Function/Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Bioreporter Strains | Genetically engineered microorganisms that produce a detectable signal in response to target analytes or general stress. | E. coli TV1061 (for general cytotoxicity) [13]. |

| Plasmonic Materials | Thin metal films used to generate the Surface Plasmon Resonance effect. | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag) [12]. |

| PCF Substrate Materials | Low-loss background materials for fabricating photonic crystal fibers, especially for THz applications. | Zeonex (cyclic olefin copolymer) [14]. |

| Immobilization Matrix | A hydrogel used to entrap and maintain the viability of bioreporter cells on sensor surfaces. | Calcium alginate hydrogel [13]. |

| Optical Fibers | The platform for guiding light in fiber-optic biosensors; can be standard or microstructured (PCF). | Multimode optical fibers; custom PCFs [13]. |

| Spectroscopic Components | Light sources and detectors for optical interrogation and signal detection. | Mini-spectrometers, photodiodes (e.g., for UV-Vis spectroscopy) [16]. |

| Simulation Software | For modeling and optimizing sensor designs before fabrication. | COMSOL Multiphysics (Finite Element Method) [14] [15]. |

Bio-optical sensors represent a powerful analytical technology that integrates a biological recognition element with an optical transducer, converting a specific biological interaction into a quantifiable signal. [17] [18] The core of these devices is the biorecognition element, which defines the sensor's selectivity and partially determines its sensitivity. [17] [19] Within the specific application of water quality monitoring, the selection of an appropriate biorecognition element is paramount for developing robust, accurate, and field-deployable sensors. [19] [5] This application note details the key characteristics, applications, and experimental protocols for four principal biological recognition elements—antibodies, enzymes, DNA, and whole cells—framed within the context of advancing bio-optical sensor research for aquatic environments.

Characteristics and Comparative Analysis of Biorecognition Elements

The performance of a bio-optical sensor is heavily influenced by the inherent properties of its chosen biorecognition element. [17] Key characteristics to consider include sensitivity, selectivity, stability, and the nature of the binding event (catalytic vs. affinity-based). [19] The table below provides a structured comparison of these elements to guide selection for water quality monitoring applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Biorecognition Elements for Bio-Optical Sensors

| Biorecognition Element | Type of Interaction | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Exemplary Water Quality Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies [17] [19] | Affinity-based (Binding) | High specificity and binding affinity; wide range of available targets. | Production can be costly and time-consuming; susceptible to denaturation; batch-to-batch variation. | Pathogens (E. coli, Legionella), algal toxins (microcystin), pesticides. |

| Enzymes [17] [19] | Catalytic (Conversion) | High catalytic turnover can amplify signal; well-characterized. | Specificity may be for a functional group rather than a single compound; stability can be limited. | Organophosphate pesticides, heavy metals (as enzyme inhibitors), phenolic compounds. |

| DNA / Nucleic Acids [17] | Affinity-based (Hybridization) | High predictability and designability; high stability; complementary base pairing. | Primarily limited to nucleic acid targets; requires sample preprocessing for non-nucleic acid analytes. | Specific pathogenic bacteria (via 16S rRNA), toxic algal species (via DNA barcodes). |

| Whole Cells [19] | Varies (Catalytic or Affinity) | Can report on functional toxicity; low cost; can be genetically engineered. | Longer response times; less specific than molecular elements; maintenance of cell viability. | Broad-range toxicity, bioavailable nutrient status, specific metabolic pollutants. |

Detailed Element Analysis and Experimental Protocols

Antibodies

Antibodies are ~150 kDa proteins that form a three-dimensional "Y"-shaped structure, with analyte binding domains located on the arms. [17] They function as affinity-based elements, where the specific binding event forms an immunocomplex. [17] For biosensing, antibodies are typically immobilized via covalent linkage to a sensor surface. [17]

Protocol: Antibody Immobilization for a Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Optical Sensor

This protocol outlines the functionalization of a gold-coated SPR chip for the detection of microcystin-LR, a common cyanotoxin.

- Chip Pre-treatment: Clean the gold sensor chip with a sequence of piranha solution (3:1 H₂SO₄:H₂O₂), deionized water, and absolute ethanol. Dry under a stream of nitrogen.

- Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Formation: Incubate the chip overnight in a 1 mM solution of 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid in ethanol. This forms a carboxyl-terminated SAM.

- Surface Activation: Rinse the chip with ethanol and water. Place it in the SPR instrument flow cell. Activate the carboxyl groups by injecting a mixture of 0.4 M EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and 0.1 M NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) in water for 10 minutes.

- Antibody Immobilization: Dilute the anti-microcystin monoclonal antibody to 50 µg/mL in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). Inject the solution over the activated surface for 20 minutes, leading to covalent amide bond formation.

- Surface Capping: Inject 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 10 minutes to deactivate any remaining NHS-esters.

- Sensor Validation: Perform a binding kinetics experiment by injecting known concentrations of microcystin-LR over the functionalized surface to establish a calibration curve.

Diagram 1: Workflow for antibody-based sensor fabrication.

Enzymes

Enzymes are biological catalysts that achieve specificity through binding cavities within their 3D structure. [17] Enzymatic biosensors are biocatalytic; the enzyme captures and converts the target analyte into a measurable product (e.g., a fluorescent or chromogenic compound). [19]

Protocol: Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticides via Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition

This protocol uses the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, whose inhibition by organophosphates can be measured optically.

- Sensor Preparation: Immobilize AChE onto a glass fiber membrane or a waveguide surface using glutaraldehyde cross-linking.

- Baseline Measurement: Place the sensor in a cuvette with phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Add the substrate acetylthiocholine and the chromogen DTNB (5,5'-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)). Monitor the increase in absorbance at 412 nm for 2 minutes due to the production of yellow 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate. This establishes the uninhibited reaction rate (V₀).

- Inhibition Phase: Incubate the sensor for 10 minutes in a water sample suspected to contain organophosphates. Rinse gently with buffer.

- Post-Inhibition Measurement: Repeat Step 2. Measure the new reaction rate (Vᵢ).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition: % Inhibition = [(V₀ - Vᵢ) / V₀] × 100%. The inhibition percentage is proportional to the pesticide concentration in the sample.

DNA (Genosensors)

Nucleic acid biosensors, or genosensors, rely on the complementary base-pairing of DNA. [17] A single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) probe is immobilized on the sensor surface to hybridize with a specific target sequence. [17] Advances include the use of Peptide Nucleic Acids (PNA), which are uncharged synthetic oligonucleotides that yield higher stability in nucleic acid binding. [17]

Protocol: Fluorometric Detection of a Pathogen-Specific Gene Sequence using a PNA Probe

This protocol describes the detection of a unique 16S rRNA sequence from E. coli.

- Probe Design and Immobilization: Design a PNA probe complementary to the target sequence. Synthesize it with a 5' amino linker. Immobilize the PNA probe on an epoxy-coated glass slide by spotting and incubating overnight in a humid chamber.

- Sample Preparation and Lysis: Collect a water sample and filter it to concentrate cells. Lyse the cells to release genetic material.

- Target Labeling and Hybridization: Amplify the target gene sequence using PCR with primers that incorporate a fluorescent label (e.g., Cy5). Denature the PCR product to produce ssDNA. Incubate the labeled ssDNA target with the PNA-functionalized slide at a specific temperature for 1 hour to allow hybridization.

- Stringency Wash: Wash the slide with a saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer at a carefully controlled temperature to remove non-specifically bound DNA.

- Signal Detection: Scan the slide using a microarray scanner or a fluorescence microscope. The fluorescence intensity at the probe spot is proportional to the amount of hybridized target.

Diagram 2: DNA hybridization detection principle.

Whole Cells

Whole microbial cells (e.g., bacteria, yeast) or bacteriophages can be used as recognition elements. [19] They can be genetically engineered to produce a signal (e.g., bioluminescence) in response to a target analyte or to report on general toxicity. [19]

Protocol: Bioluminescence-Based Whole-Cell Sensor for Water Toxicity Screening

This protocol uses recombinant bacteria that produce bioluminescence constitutively. A decrease in light output indicates metabolic toxicity.

- Strain Preparation: Use a freeze-dried aliquot of a bioluminescent bacterial strain, such as Vibrio fischeri or a recombinant E. coli.

- Cell Hydration and Recovery: Rehydrate the cells according to the manufacturer's instructions in a non-toxic recovery medium. Incubate until a stable baseline luminescence is achieved.

- Exposure to Sample: Mix a consistent volume of the bacterial suspension with an equal volume of the water sample in a multi-well plate.

- Signal Measurement: Immediately place the plate in a luminometer or a optical plate reader equipped with a sensitive CCD camera. Measure the luminescence intensity every 5 minutes for a period of 30 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage inhibition of bioluminescence relative to a negative control (e.g., clean water) at the 15-minute time point: % Inhibition = [1 - (Lsample / Lcontrol)] × 100%.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and reagents commonly used in the development and application of bio-optical sensors for water quality research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Bio-Optical Sensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| EDC & NHS [17] | Carboxyl group activators for covalent immobilization of biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, DNA). | Forming amide bonds between a sensor surface and proteins or aminated DNA. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A homobifunctional crosslinker for immobilizing biomolecules, particularly on aminated surfaces. | Crosslinking enzymes like AChE to a chitosan-coated sensor surface. |

| Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Probes [17] | Uncharged synthetic DNA analogs used as highly stable and specific hybridization probes. | Detecting specific bacterial rRNA sequences with high specificity and sensitivity. |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Signal amplification tags; used in colorimetric or surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) assays. | Conjugating with antibodies for visual detection of contaminants in lateral flow assays. |

| Bioluminescent Bacterial Strains [19] | Whole-cell bioreporters that produce light as a functional signal of metabolic activity or stress. | Vibrio fischeri for broad-spectrum toxicity monitoring in wastewater. |

| Chromogenic Substrates | Enzyme substrates that yield a colored product upon catalytic conversion. | DTNB with AChE for spectrophotometric detection of enzyme activity and inhibition. |

Optical biosensors have emerged as a transformative technology for water quality monitoring, addressing critical limitations of traditional methods. Conventional techniques, which rely on manual sample collection, preservation, and laboratory analysis, are associated with low sampling efficiency, long response times, and high economic costs, and they cannot guarantee the accuracy and real-time determination of monitoring data [5]. Optical biosensors overcome these challenges by providing rapid, accurate, and cost-effective solutions for detecting biological materials, pathogens, and specific chemical substances in water [20]. The global biosensors market, valued at $26.75 billion in 2022, reflects this technological shift and is projected to reach $45.95 billion by 2030, growing at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 7.00% [20].

The integration of optical biosensors into environmental monitoring represents a convergence of biochemistry, material science, and photonics. These devices operate by converting a biological response into a quantifiable optical signal—such as changes in absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, or refractive index—when a target analyte binds to a biological recognition element [21]. This capability for real-time data acquisition and continuous monitoring makes them particularly valuable for protecting water resources, maintaining ecological balance, and safeguarding human health [5]. As concerns about water pollution and freshwater scarcity intensify globally, optical biosensors are transitioning from specialized laboratory tools to essential environmental sentinels deployed in diverse aquatic environments.

Key Optical Biosensing Technologies and Principles

The operational principle of all optical biosensors involves the detection of an optical signal change resulting from the interaction between a biological recognition element and the target analyte. The choice of optical technique depends on the specific application, required sensitivity, and the nature of the target contaminant.

Table 1: Fundamental Types of Optical Biosensors for Water Quality Monitoring

| Technology | Transduction Principle | Typical Measurands | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric | Measures change in absorbance or color intensity | Heavy metals, nutrients, pesticides | Simple instrumentation, cost-effective, suitable for field use |

| Fluorescence | Measures change in fluorescence intensity or lifetime | Organic pollutants, bacteria, toxins | High sensitivity, potential for multiplexing |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures change in refractive index near a metal surface | Pathogens, toxins, small molecules | Label-free, real-time monitoring |

| Chemiluminescence | Measures light emission from a chemical reaction | Specific ions, enzyme activities | High signal-to-noise ratio, simple equipment |

| Optical Fiber-Based | Utilizes optical fibers to guide light to and from sensing region | pH, dissolved oxygen, various contaminants | Remote sensing capability, small size |

Recent advancements in nanotechnology and material science have significantly enhanced the performance of these biosensors. The use of nanomaterials improves sensitivity and allows for faster, more accurate measurements at lower concentrations of target substances [20]. Furthermore, the miniaturization of biosensors has enabled the development of portable, wearable devices that can monitor water quality in real-time, moving analysis from the central laboratory directly to the field [20].

Application Notes: Optical Biosensors as Environmental Sentinels

Monitoring Parameters in Various Water Matrices

Optical biosensors have been successfully deployed across diverse aquatic environments, each with distinct monitoring requirements and challenges.

Table 2: Key Water Quality Parameters Monitored with Optical Biosensors

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Significance for Water Quality | Common Biosensing Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | Chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) | Indicator of algal biomass and eutrophication | Fluorescence, colorimetric |

| Physical | Turbidity, Total Suspended Solids (TSS) | Measures water clarity and suspended particles | Scattering, optical absorption |

| Chemical | pH, Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | Fundamental indicators of water health | Fluorescence quenching, colorimetric |

| Chemical | Colored Dissolved Organic Matter (CDOM) | Natural organic matter affecting light absorption | Fluorescence spectroscopy |

| Chemical | Nutrients (Nitrate, Phosphate) | Indicators of potential eutrophication | Colorimetric, fluorescence |

| Chemical | Specific Pollutants (heavy metals, pesticides) | Direct measurement of toxic contaminants | Various competitive and inhibition assays |

For instance, in surface water monitoring, a study utilized GF-4 geosynchronous optical satellite data to establish a Chl-a reversal model (PGS-C) for analyzing distribution in the Yangtze River estuary. The results demonstrated a remarkable correlation coefficient of 0.9123, indicating high consistency between modeling values and field measurements [5]. This showcases the powerful application of remote sensing technologies complemented by ground-truthed biosensor data for large-scale water quality assessment.

System Architecture for Remote Monitoring

The implementation of optical biosensors as effective environmental sentinels requires integration into a comprehensive remote monitoring system. These systems typically consist of four distinct layers:

- Data Acquisition Layer: Comprises the optical biosensors themselves, which can be deployed as fixed stations, mobile systems on vehicles or ships, or underwater drones [5].

- Data Transmission Layer: Utilizes Internet of Things (IoT) technology, including protocols like LoRaWAN (Long Range Wide Area Network), to transmit data from the field to central systems [5].

- Data Storage Layer: Employs cloud platforms or dedicated servers for secure data storage and management.

- Data Processing Layer: Involves analytics platforms, increasingly enhanced by artificial intelligence (AI), for data interpretation, visualization, and decision support [5] [21].

Figure 1: System Architecture for Remote Water Quality Monitoring Using Optical Biosensors

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Deployment and Operation of a Multi-Parameter Optical Biosensor System

Objective: To continuously monitor key water quality parameters (turbidity, pH, dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll-a) in a freshwater body using an integrated optical biosensor system.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multi-parameter optical biosensor platform (e.g., YSI EXO2 or equivalent)

- Sensor calibration standards:

- pH buffer solutions (pH 4.01, 7.00, 10.01)

- Turbidity calibration standards (0, 10, 100, 1000 NTU)

- Dissolved oxygen calibration solution (zero oxygen solution, water-saturated air)

- Deionized water for rinsing

- Isopropyl alcohol and soft cloth for cleaning

- Anti-fouling guards or copper alloy components

Procedure:

Pre-Deployment Calibration:

- Power on the biosensor platform and allow it to initialize.

- Calibrate the pH sensor:

- Rinse the pH sensor with deionized water.

- Immerse the sensor in pH 7.00 buffer solution, wait for readings to stabilize, and confirm calibration.

- Repeat with pH 10.01 or 4.01 buffer for a two-point calibration.

- Calibrate the turbidity sensor:

- Ensure the sensor window is clean and dry.

- Using a uniform suspension of formazin or equivalent standard, follow the manufacturer's instructions for multi-point calibration across the expected measurement range (e.g., 0-1000 NTU).

- Calibrate the dissolved oxygen sensor:

- Perform a zero-oxygen calibration by placing the sensor in a zero-oxygen solution and adjusting the reading to zero.

- Perform a saturated air calibration by exposing the moistened sensor to water-saturated air and setting the value to 100% saturation (adjust for atmospheric pressure and temperature as per manufacturer's instructions).

- Verify all calibrations and secure the sensor guard.

Field Deployment:

- Select a deployment site that is representative of the water body, with consideration for depth, flow conditions, and accessibility.

- Securely mount the sensor platform to a fixed structure (e.g., pier, buoy, or dedicated mounting pole) ensuring sensors are at the desired depth (typically 0.5-1 meter below the surface for most applications).

- Verify the secure connection of all communication cables (if applicable) and power supply.

- Configure the data logging interval (e.g., 15-minute intervals for continuous monitoring) and activate remote data transmission.

- Record the GPS coordinates, deployment time, and initial readings in the field log.

Data Collection and Maintenance:

- Data is automatically collected, transmitted via IoT protocols (e.g., LoRaWAN, cellular) to a cloud gateway, and stored in a centralized database [5].

- Perform routine maintenance every 2-4 weeks:

- Visually inspect for biofouling, debris, or physical damage.

- Gently clean optical surfaces with soft cloth and isopropyl alcohol if necessary.

- Verify sensor accuracy against a portable reference instrument if available.

- Replace anti-fouling components as required.

- Re-calibrate sensors according to the manufacturer's recommended schedule or when data drift is observed (typically every 1-3 months).

Protocol 2: AI-Enhanced Detection of Contaminants Using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Objective: To detect and quantify specific waterborne pathogens (e.g., E. coli) using an AI-enhanced SPR biosensor.

Materials and Reagents:

- SPR biosensor instrument

- Carboxylated or amine-functionalized gold sensor chips

- N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Specific antibody against target pathogen (e.g., anti-E. coli antibody)

- Ethanolamine hydrochloride solution (1.0 M, pH 8.5)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4) with 0.005% Tween 20 (PBST)

- Glycine-HCl solution (10 mM, pH 2.5) for regeneration

- Standard solutions of target pathogen for calibration

- Water samples (filtered through 0.45 μm membrane)

Procedure:

Sensor Chip Functionalization:

- Dock a clean gold sensor chip in the SPR instrument.

- Prime the flow system with PBST at a flow rate of 5 μL/min until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Activate the carboxylated dextran surface by injecting a fresh mixture of EDC (0.4 M) and NHS (0.1 M) for 7 minutes.

- Dilute the specific antibody in sodium acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 5.0) to a concentration of 50 μg/mL.

- Inject the antibody solution for 15 minutes to achieve covalent immobilization via amine coupling.

- Block any remaining activated ester groups by injecting ethanolamine solution (pH 8.5) for 7 minutes.

- Wash the system with PBST until a stable baseline is achieved. The functionalized sensor chip is now ready for use.

Sample Analysis with AI-Enhanced Data Processing:

- Establish a calibration curve by injecting a series of standard pathogen solutions (e.g., 10^2 to 10^6 CFU/mL) in PBST. The SPR response (resonance unit shift, RU) is recorded for each concentration.

- Inject filtered water samples (unknowns) using the same flow conditions (contact time: 5 minutes, dissociation time: 3 minutes).

- Regenerate the sensor surface after each sample injection using a 1-minute pulse of glycine-HCl (pH 2.5) to dissociate the antibody-pathogen complex, followed by re-equilibration with PBST.

- The response data (sensograms) for both standards and unknowns are processed by a machine learning algorithm (e.g., a hybrid model like Genetic Algorithm-Support Vector Machine, GA-SVM) [5]. The AI model is trained on the calibration dataset to recognize the binding pattern and quantify the pathogen concentration in the unknown samples with high accuracy and reliability.

- The AI model outputs the predicted concentration along with a confidence score for each measurement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of optical biosensor technologies requires specific reagents and materials to ensure optimal performance and accurate results.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Optical Biosensing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Recognition Elements (Antibodies, Aptamers, Enzymes, Whole Cells) | Provides specificity for the target analyte; the core of the biosensor's selectivity. | Stability in environmental conditions, binding affinity (Kd), specificity (cross-reactivity), and shelf life are critical. |

| Fluorescent Dyes/Labels (e.g., Fluorescein, Rhodamine, Quantum Dots) | Tags for generating or enhancing optical signals in fluorescence-based biosensors. | High quantum yield, photostability, compatibility with excitation/emission hardware, and minimal non-specific binding. |

| Sensor Chip Substrates (Gold for SPR, Functionalized Glass, Polymers) | Physical platform for immobilizing biological recognition elements. | Surface chemistry, optical properties, reproducibility, and cost. Functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, amine) must match immobilization strategy. |

| Immobilization Chemistry Kits (e.g., EDC/NHS, SAM formation reagents) | Covalently attaches recognition elements to the sensor surface. | Reaction efficiency, stability of the formed bond, and ability to maintain biorecognition element activity post-immobilization. |

| Buffer and Calibration Standards | Provides a controlled chemical environment for assays and enables sensor calibration. | Ionic strength, pH, and absence of contaminants that could interfere with the assay or foul the sensor. |

| Anti-Fouling Agents/Coatings (e.g., PEG, Zwitterionic polymers, Copper alloys) | Prevents non-specific adsorption and biofilm growth on sensor surfaces. | Effectiveness against local biofouling communities, longevity, and compatibility with the sensing mechanism. |

Future Outlook and Integration with Emerging Technologies

The future trajectory of optical biosensors is intimately linked with advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), and cloud computing. The integration of AI, particularly machine learning and deep learning algorithms, is revolutionizing data analysis from optical biosensors by improving sensitivity, specificity, and multiplexing capabilities through intelligent signal processing, pattern recognition, and automated decision-making [21]. For example, AI models like the Genetic Algorithm-Support Vector Machine (GA-SVM) have demonstrated extremely high prediction accuracy (RMSE = 0.04474, R² = 0.96580) in forecasting water quality trends, providing an effective technical tool for proactive water resource management [5].

The convergence of biosensors with IoT technology offers immense growth potential, particularly in the development of comprehensive environmental monitoring networks for smart cities and watershed management [20]. These integrated systems enable real-time data transmission to cloud platforms, where information becomes accessible via web-based and mobile dashboards, allowing researchers and water managers to monitor water quality parameters remotely using internet-connected devices [5].

Figure 2: AI-Enhanced Data Processing Workflow for Optical Biosensors

However, several challenges must be addressed to fully realize the potential of next-generation optical biosensors. Data security remains a significant concern as biosensors become more integrated with digital health and environmental monitoring systems [20]. Additionally, issues related to technological standardization, regulatory hurdles, and the complexity of integration with existing monitoring infrastructure present barriers to widespread adoption [20]. The high initial costs of advanced biosensor technology can also be prohibitive for some markets, particularly in developing regions [20]. Ongoing research focuses on overcoming these limitations through the development of more robust, cost-effective, and user-friendly biosensing platforms that can operate reliably in diverse environmental conditions.

Optical biosensors have unequivocally transitioned from sophisticated laboratory tools to indispensable environmental sentinels, fundamentally reshaping our approach to water quality monitoring. This trajectory is propelled by their unparalleled capabilities for real-time, sensitive, and specific detection of waterborne contaminants across diverse matrices. The integration of these biosensors with AI-powered analytics and IoT connectivity creates a powerful paradigm for comprehensive water resource management, enabling early warning systems, predictive analytics, and data-driven decision-making [5] [21]. As advancements in nanotechnology, material science, and data analytics continue to converge, optical biosensors are poised to become even more pervasive, affordable, and integral to global efforts aimed at safeguarding water resources, ensuring ecosystem health, and protecting public health for future generations.

Detection of Waterborne Pathogens and Emerging Contaminants

Within the broader research on bio-optical sensors for water quality monitoring, the rapid and specific detection of pathogenic microorganisms in complex water matrices remains a critical challenge. Traditional microbial detection methods, such as culture-based techniques, are often inadequate for modern needs, typically requiring 18 to 72 hours to provide results and struggling to detect low concentrations of pathogens or viable but non-culturable (VBNC) organisms [22] [23]. These limitations hinder effective response to contamination events and outbreak management.

The emergence of advanced molecular methods and biosensing technologies has initiated a paradigm shift in waterborne pathogen surveillance. These innovative approaches leverage biological recognition elements (e.g., antibodies, DNA, aptamers) coupled with transducers that convert biological interactions into quantifiable signals [24] [22]. When integrated with bio-optical sensing platforms—which utilize optical phenomena such as absorbance, fluorescence, and scattering—these systems enable sensitive, specific, and rapid detection of bacterial and viral targets directly in complex water environments, providing a powerful tool for ensuring water safety [25].

Current Technologies for Pathogen Detection in Water

A spectrum of technologies is available for detecting waterborne pathogens, each with distinct operational principles, advantages, and limitations. The transition from conventional to modern methods represents a significant advancement in the capability to monitor water quality effectively.

Traditional and Molecular Methods

Conventional culture-based methods, such as multiple-tube fermentation and membrane filtration, are considered the historical "gold standard." They are simple and cost-effective but are characterized by being highly laborious, time-consuming (taking up to several days), and unable to detect non-culturable pathogens [22] [23]. Their low sensitivity for detecting contaminants present at low concentrations poses a health risk, as many waterborne pathogens remain infectious even at minimal levels [22].

Molecular-based methods overcome several of these limitations by targeting specific genetic material (DNA or RNA) or proteins of the target analyte. These methods provide faster, highly sensitive, and specific detection, with the ability to detect viable but non-culturable cells [22] [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Pathogen Detection Method Categories

| Method Category | Key Examples | Typical Detection Time | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-Based | Membrane Filtration, Multiple-Tube Fermentation | 18 - 72 hours [22] | Low cost; considered "gold standard" [22] | Time-consuming; misses VBNC cells; low sensitivity [22] [23] |

| Molecular | qPCR, LAMP, ELISA | 2 - 8 hours [23] | High sensitivity & specificity; detects VBNC cells [22] [23] | Requires specialized equipment & trained personnel; susceptible to inhibitors [22] |

| Biosensors | Optical, Electrochemical, Microfluidic chips | Minutes - 1 hour [24] [22] | Rapid, portable, highly sensitive, potential for on-site use [24] [22] | Requires calibration; biofouling can be an issue in long-term deployment [5] |

Key molecular tools include:

- Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR): This technique allows for the quantitative detection of specific pathogen DNA sequences with high sensitivity, often detecting as few as 2-10 gene copies per reaction [23]. For example, it can detect enteroviruses at concentrations as low as 2 copies per liter in surface water [23].

- Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): An isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique that is rapid and can be more robust to inhibitors than PCR, making it suitable for field-deployable applications [24].

- Microarrays (e.g., PhyloChip, ViroChip): High-density platforms that enable the simultaneous interrogation of thousands of microbial taxa in a single assay via nucleic acid hybridization, useful for broad pathogen surveillance and discovery [23].

Despite their advantages, molecular methods often require extensive sample pre-treatment, specialized equipment, and highly trained personnel. Their reproducibility can also be impacted by inhibitors present in complex water samples [22].

The Rise of Biosensors

Biosensors address many hurdles in traditional pathogen monitoring. A biosensor comprises a biological recognition element (e.g., antibody, DNA probe, aptamer, enzyme) that specifically binds to the target pathogen and a transducer (e.g., optical, electrochemical) that converts the binding event into a measurable signal [24] [22].

Compared to conventional methods, biosensors offer detection without extensive sample pre-concentration, which significantly reduces analysis time. They are characterized by high specificity and sensitivity, low cost, ease of use, and potential for miniaturization, making them attractive for on-site, real-time monitoring [22]. Optical biosensors, in particular, align with the theme of bio-optical sensing by exploiting changes in light properties (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence, refractive index) upon pathogen capture.

Table 2: Performance of Selected Detection Methods for Key Waterborne Pathogens

| Pathogen | Disease Association | qPCR Detection Limit | Culture-Based Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter jejuni | Gastroenteritis | 10 gene copies [23] | Culture-based, time-consuming [23] |

| Escherichia coli O157 | Gastroenteritis, HUS | 7 CFU [23] | Culture-based, time-consuming [23] |

| Adenoviruses | Gastroenteritis, Respiratory illness | 8 gene copies [23] | Not applicable |

| Noroviruses | Gastroenteritis | <10 gene copies [23] | Not applicable |

| Cryptosporidium parvum | Cryptosporidiosis | 1.65 oocysts [23] | Microscopy, difficult [23] |

Advanced Bio-Optical Sensing Platforms

Innovative sensor designs are enhancing the capabilities for in-situ water quality monitoring. These platforms integrate multiple optical techniques to provide comprehensive water quality assessment.

Multiparameter Optical Sensor Probe

A recent development is a submersible sensor probe that combines UV/Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy with a flexible, open-data processing platform [25]. This design overcomes the limitation of many commercial sensors, which have fixed configurations and static data processing.

Key features of this integrated platform include:

- Synchronous Data Acquisition: Absorbance (in a 180° configuration) and fluorescence (in a 90° geometry) measurements are taken simultaneously on a water sample pumped through a 10 mm pathlength flow cell, minimizing external interference [25].

- Adaptable Hardware: A miniaturized deuterium-tungsten light source (200-1100 nm) enables broad-spectrum UV/Vis measurements. An LED array with four slots allows excitation at different wavelengths for fluorescence, with a miniature spectrometer (225-1000 nm) capturing full emission spectra [25].

- Modular Software: An open data processing platform allows users to adapt quantification algorithms, turbidity compensation, and data fusion methods for specific applications [25].

This sensor can be deployed directly in water bodies and groundwater wells, enabling high-resolution spatiotemporal monitoring essential for pinpointing contamination sources and tracking dynamic pollution events [25].

Detectable Parameters and Their Optical Signatures

This multi-method approach allows for the detection of various parameters indicative of microbial contamination and water quality.

Table 3: Optical Parameters for Water Quality and Pathogen Indicator Monitoring

| Parameter | Optical Method | Wavelength (Ex/Em or Abs) | Proxy For / Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan-like Fluorescence (TLF) | Fluorescence | λex = 280 nm / λem = 365 nm [25] | Biological activity, microbial contamination [25] |

| Humic-like Fluorescence (HLF) | Fluorescence | λex = 280 nm / λem = 450 nm [25] | Dissolved organic matter (allochthonous & autochthonous) [25] |

| Chlorophyll a | Fluorescence | λex = 430 nm / λem = 675-750 nm [25] | Algal biomass [25] |

| Phycocyanin | Fluorescence | λex = 590 nm / λem = 640-690 nm [25] | Cyanobacterial biomass [25] |

| Nitrate | UV/Vis Absorbance | A~217-240 nm [25] | Eutrophication, nutrient loading [25] |

| Spectral Absorption (SAC254) | UV/Vis Absorbance | A~254 nm [25] | Organic load in water [25] |

| Turbidity | Scattered Light / Abs | A~>800 nm [25] | Suspended particulate matter, water clarity [25] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for setting up and applying bio-sensing and molecular techniques for pathogen detection in water.

Protocol: Detection of Microbial Contamination via Tryptophan-like Fluorescence

Principle: Tryptophan-like fluorescence (TLF) is an effective indicator of recent biological activity and microbial contamination, often correlating with the presence of fecal bacteria in water bodies [25]. This protocol utilizes a submersible fluorescence sensor for in-situ monitoring.

I. Equipment and Reagents

- Submersible sensor probe with UV/Vis and fluorescence capability (e.g., design per [25])

- L-Tryptophan standard for calibration [25]

- Deionized water

- Sampling bottles

II. Sensor Calibration

- Prepare a series of L-Tryptophan standard solutions in deionized water (e.g., 0, 10, 50, 100, 500 µg/L).

- Submerge the sensor probe in each standard solution or pump standards through the flow cell.

- Record the fluorescence intensity at an excitation of 280 nm and emission of 365 nm for each standard [25].

- Generate a calibration curve (Fluorescence Intensity vs. Tryptophan Concentration).

III. Field Measurement and Data Collection

- Deploy the sensor at the monitoring site (river, lake, well).

- Allow water to flow through the internal measurement cell using the integrated pump.

- Initiate measurement cycle: record synchronous UV/Vis (200-1100 nm) and fluorescence spectra.

- The internal processor converts the fluorescence signal at λex/λem = 280/365 nm to a TLF value based on the calibration curve.

- Data can be transmitted in real-time to a cloud platform for visualization and alert generation.

IV. Data Interpretation

- Elevated TLF levels above a site-specific baseline indicate potential microbial contamination.

- TLF should be correlated with other parameters (e.g., HLF, nitrate) to distinguish contamination sources.

Protocol: qPCR-Based Detection of Specific Bacterial Pathogens

Principle: This protocol uses quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect and quantify a specific bacterial pathogen, E. coli O157, by targeting a unique segment of its DNA with high sensitivity (down to 7 CFU per reaction) [23].

I. Equipment and Reagents

- qPCR instrument

- Water sample collection kits

- DNA extraction kit (for water samples)

- Primers and probes specific for E. coli O157 [23]

- qPCR master mix

- Nuclease-free water

- Positive control (E. coli O157 DNA) and negative control (no-template water)

II. Sample Collection and Concentration

- Collect a sufficient volume of water (often 100 mL to several liters).

- Concentrate bacterial cells from water via membrane filtration or immunomagnetic separation (IMS) to enhance detection sensitivity.

III. DNA Extraction

- Extract genomic DNA from the concentrated sample or filter using a commercial DNA extraction kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Elute the DNA in a small volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of nuclease-free water.

- Quantify DNA purity and concentration using a spectrophotometer.

IV. qPCR Setup and Amplification

- Prepare the qPCR reaction mix on ice:

- 10 µL of 2x qPCR Master Mix

- 1 µL of Forward Primer (10 µM)

- 1 µL of Reverse Primer (10 µM)

- 0.5 µL of TaqMan Probe (10 µM)

- 2.5 µL of Nuclease-free water

- 5 µL of DNA template

- Total Reaction Volume: 20 µL

- Load the reactions into the qPCR instrument.

- Run the following thermocycling program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes (1 cycle)

- Amplification: 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute (40 cycles) [23]

- Data Collection: Acquire fluorescence signal during the 60°C annealing/extension step of each cycle.

V. Data Analysis

- Analyze the amplification curves and determine the Cycle Threshold (Ct) value for each sample.

- Quantify the pathogen concentration by comparing the Ct values to a standard curve generated from samples with known concentrations of E. coli O157.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of rapid pathogen detection methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pathogen Detection

| Category / Item | Specific Example | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Recognition Elements | |||

| Antibodies | Anti-E. coli O157 antibody [24] | Specific capture and detection of target pathogen | High affinity and specificity |

| DNA Probes | Oligonucleotides for 16S rRNA or virulence genes [23] | Hybridization for detection and identification | Target-specific sequence |

| Aptamers | Synthetic ssDNA/RNA for Campylobacter [24] | Synthetic recognition element | High stability, tunable affinity |

| Molecular Assay Components | |||

| Primers & Probes | E. coli O157-specific TaqMan assay [23] | Target amplification and detection in qPCR | Defines assay specificity and sensitivity |

| PCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer | Enzymatic amplification of DNA | High efficiency and robustness |

| Calibration Standards | |||

| Fluorescence Standards | L-Tryptophan, Quinine Sulfate [25] | Calibration of fluorescence sensors | Known quantum yield, stable |

| Nucleic Acid Standards | GBlocks, Plasmid DNA with target sequence [23] | qPCR standard curve generation | Accurate quantification |

| Sample Preparation | |||

| Immunomagnetic Beads | Beads coated with specific antibodies [23] | Pathogen concentration from large volumes | Improves detection limits |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Commercial kits for water samples | Isolation of PCR-quality DNA | Removes PCR inhibitors |

The integration of advanced bio-optical sensors and molecular detection technologies is revolutionizing the monitoring of pathogens in complex water matrices. Moving from slow, lab-bound culture methods to rapid, in-situ, and often multiplexed sensing platforms enables a more proactive approach to safeguarding public health.

Key advancements include the development of flexible, multi-parameter optical probes that provide real-time data on both specific pathogen indicators and general water quality [25], and the refinement of molecular techniques like qPCR that offer exceptional sensitivity and specificity for target organisms [23]. The future of this field lies in the continued miniaturization and integration of these technologies, the development of more robust and stable biorecognition elements, and the creation of intelligent, networked sensor systems that can provide early warning of contamination events across water infrastructure. By leveraging these advanced tools, researchers and water quality professionals can better address the persistent and evolving challenge of waterborne pathogens.

Application Notes: Biosensor Platforms for Emerging Contaminants

Biosensors represent a promising biotechnological alternative to conventional analytical techniques for monitoring emerging contaminants (ECs) in water environments, offering advantages such as low cost, simplicity, fast processing, sensitivity, and portability [26]. These devices employ a biological recognition element to selectively capture an analyte and a signal transduction element to convert the recognition event into detectable output signals [27]. The following sections detail the application and performance of major biosensor types for EC detection.

Performance Comparison of Biosensor Types

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the main biosensor classes used for detecting pharmaceuticals, endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), and pesticides in water samples.

Table 1: Comparison of Biosensor Platforms for Emerging Contaminant Monitoring

| Biosensor Type | Biorecognition Element | Typical Transduction Mechanism | Key Advantages | Example Contaminant & Detection Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-Based | Enzyme (e.g., acetylcholinesterase) | Electrochemical, Optical, Thermal | High specificity and sensitivity; Rapid and portable electrochemical systems [26] | Pesticides (organophosphates) - Varies by compound |

| Antibody-Based (Immunosensor) | Antibody (Immunoglobulin) | Label-free (impedance, refractive index) or Labeled (fluorescence, enzymes) [26] | High specificity and affinity for targets; Versatile platform | Ciprofloxacin (antibiotic) - 10 pg/mL [26] |

| Nucleic Acid-Based (Aptasensor) | DNA or RNA aptamer (selected via SELEX) [26] [27] | Optical, Electrochemical, Piezoelectric | Chemical synthesis simplicity; High stability and affinity [26] | Various EDCs and pharmaceuticals - Varies by aptamer |

| Whole Cell-Based | Microbial cells (e.g., E. coli), fungi, algae | Optical, Electrochemical | Self-replicating, robust, easily engineered [26] | Pyrethroid insecticide - 3 ng/mL [26] |

| Toxicity Testing Biosensor | Nuclear receptors (ER, AR, TR) or Transport proteins | Fluorescence (FP, FRET), SPR, QCM [27] | Provides biological activity/toxicity data, not just chemical identity [27] | Endocrine disruptors (via receptor binding) - Varies by assay |

Advanced Optical Sensing Mechanisms

The integration of functionalized low-dimensional nanomaterials has advanced optical biosensing techniques, enhancing their sensitivity and specificity. Key mechanisms include Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR), photoluminescence (PL), Surface Enhancement Raman Scattering (SERS), and nanozyme-based colorimetric strategies [9]. These optical biosensors are gaining popularity due to their portability, miniaturization, and rapid responsiveness, making them suitable for at-home diagnostics and continuous molecular monitoring [9].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for fabricating and applying different biosensor types for the detection of ECs in water samples.

Protocol: Impedimetric Immunosensor for Antibiotic Detection

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a label-free impedimetric immunosensor for the detection of ciprofloxacin (CIP) antibiotics, based on the work of Ionescu et al. [26].

- Objective: To quantify ciprofloxacin concentrations in water samples via specific antigen-antibody binding measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

- Principle: The formation of an antigen-antibody complex on an electrode surface alters the interfacial properties, triggering a measurable change in impedance.

- Materials:

- Working Electrode: Gold or Screen-printed carbon electrode.

- Anti-CIP Antibody: Monoclonal or polyclonal specific to ciprofloxacin.

- Blocking Agent: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

- Electrochemical Cell: Potentiostat with impedance capability.

- Buffer Solutions: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for washing and dilution.

- Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the working electrode according to manufacturer's protocols (e.g., electrochemical cycling in sulfuric acid for gold electrodes).

- Antibody Immobilization: Incubate the electrode with a solution of anti-CIP antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Wash thoroughly with PBS buffer to remove unbound antibodies.

- Surface Blocking: Incubate the electrode with a 1% BSA solution for 30 minutes to block non-specific binding sites. Wash again with PBS.

- Sample Incubation: Expose the functionalized electrode to the standard or sample solution containing CIP for 20-30 minutes.

- Impedance Measurement: Measure the electrochemical impedance spectrum in a suitable redox probe solution (e.g., 5mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] in PBS). Apply a small sinusoidal potential (e.g., 10 mV amplitude) over a frequency range (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz) at a fixed DC potential.

- Data Analysis: The charge transfer resistance (Rₜ), derived from the impedance data, is proportional to the CIP concentration. Plot Rₜ vs. log[CIP] to generate a calibration curve.

- Performance: This method achieved a detection limit as low as 10 pg/mL for CIP [26].

Protocol: Aptamer-Based Biosensor using Fluorescence Polarization

This protocol describes a toxicity testing biosensor that detects the binding of EDCs to nuclear receptors, using fluorescence polarization (FP) as a readout [27].

- Objective: To identify chemicals that bind to the Thyroid Hormone Receptor (TR) as a potential mechanism of endocrine disruption.

- Principle: FP measures the change in the rotational speed of a small fluorescent tracer molecule. When a fluorescently-labeled thyroid hormone (Tracer) is bound by a large receptor (TR), its rotation is slow, and FP is high. If an EDC in the sample displaces the Tracer from the receptor, the free Tracer rotates rapidly, resulting in a low FP signal.

- Materials:

- Recombinant Nuclear Receptor: Thyroid Hormone Receptor beta (TRβ) ligand binding domain.

- Fluorescent Tracer: Fluorescently-labeled T3 (Thyronine).

- Assay Buffer: Optimized buffer (e.g., containing salts, DTT, glycerol).

- Microplate: Black, low-volume, 384-well microplate.

- FP Reader: Plate reader capable of measuring fluorescence polarization/anisotropy.

- Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare the receptor and tracer in assay buffer. Pre-titrate to determine optimal concentrations.

- Assay Setup: In each well, add:

- Assay buffer (to bring to total volume).

- Test compound (EDC) or control.

- Recombinant TRβ.

- Fluorescent Tracer.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate in the dark for 2 hours at room temperature to reach binding equilibrium.

- FP Measurement: Read the plate using the FP reader. Excitation is typically in the 480-490 nm range, and emission is measured at 520-530 nm for a FITC-labeled tracer.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the % displacement of the tracer by the test compound relative to controls (vehicle only for 100% binding, unlabeled T3 in excess for 0% binding). A dose-response curve can be generated to estimate the potency (IC₅₀) of the EDC.

- Application: This method is suitable for high-throughput screening of environmental samples or chemical libraries for thyroid hormone disruption potential [27].

Protocol: Whole-Cell Biosensor for Pyrethroid Insecticide

This protocol is based on the development of a label-free, cell-based biosensor using Escherichia coli for monitoring pyrethroid insecticides [26].

- Objective: To detect pyrethroid insecticides via a microbial whole-cell response.