Biomedical Optics: Principles, Imaging Technologies, and Applications in Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and cutting-edge applications of biomedical optics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Biomedical Optics: Principles, Imaging Technologies, and Applications in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and cutting-edge applications of biomedical optics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores how light interacts with biological tissues through absorption, scattering, and fluorescence, and details key technologies like Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), Photoacoustic Tomography (PAT), and near-infrared spectroscopy. The scope extends from foundational concepts and methodological applications to practical troubleshooting in optical device development and a comparative analysis with other imaging modalities. The content aims to serve as a critical resource for leveraging optical imaging in drug discovery, diagnostic applications, and preclinical research.

Light and Tissue: Core Principles of Light-Tissue Interaction

Biomedical optics is a cornerstone of modern life sciences, providing non-invasive tools for research, diagnostics, and therapy. This field leverages the fundamental interactions between light and biological matter—primarily absorption, scattering, and fluorescence—to investigate and influence processes at molecular, cellular, tissue, and organ levels [1]. These light-based techniques offer significant advantages including non-contact measurement, high sensitivity down to single molecules, rapid real-time data acquisition, and the ability to observe dynamic biological processes across various timescales [1]. This whitepaper details the core principles, measurement methodologies, and research applications of these fundamental interactions, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals advancing optical technologies in medicine.

Core Principles of Light-Tissue Interactions

Photons interacting with biological tissue undergo several key processes that form the basis for most biophotonic techniques. The structural, functional, mechanical, biological, and chemical properties of biological materials are studied through these light interactions [1].

Absorption

Absorption occurs when photon energy is transferred to a molecule, promoting it to an excited electronic state. The absorbing molecule converts this photon energy into electrical, vibrational, or thermal energy [2]. This process is quantified by the absorption coefficient µa, which indicates the probability of absorption per unit path length.

- Energy Conversion: The absorbed energy may be re-emitted through mechanisms like fluorescence, converted to heat through photothermal processes, or drive photochemical reactions [2].

- Molecular Specificity: Absorption is highly molecule-specific, with endogenous chromophores including hemoglobin, NADP(H), flavin, elastin, and cytochrome exhibiting characteristic absorption spectra [1].

Scattering

Scattering changes the trajectory of light photons upon interaction with microscopic variations in tissue refractive index. Unlike absorption, scattering typically involves no energy loss. The primary forms are elastic (Rayleigh and Mie) and inelastic (Raman) scattering.

- Elastic Scattering: Photons change direction without wavelength change. This phenomenon underpins techniques like Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), which detects changes in refractive index to visualize tissue architecture [1].

- Inelastic Scattering: Photons change direction and undergo energy/wavelength shifts, providing molecular vibration information. Raman scattering is molecule-specific, visualizing distributions of proteins, lipids, and DNA, though its weak signal often requires enhancement techniques like coherent Raman scattering (CRS) [1].

Fluorescence

Fluorescence is the emission of longer-wavelength light following photon absorption. Molecules (fluorophores) absorb specific wavelength light, enter an excited state, and emit light upon returning to ground state.

- Endogenous vs. Exogenous: Fluorescence can originate from native fluorophores (e.g., NADP(H), flavins) or introduced labels. Fluorescence imaging and Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) provide spatial distribution and microenvironment information [1].

- Contrast Mechanism: This emission provides high molecular contrast, enabling visualization of specific molecular markers and cellular conditions [1].

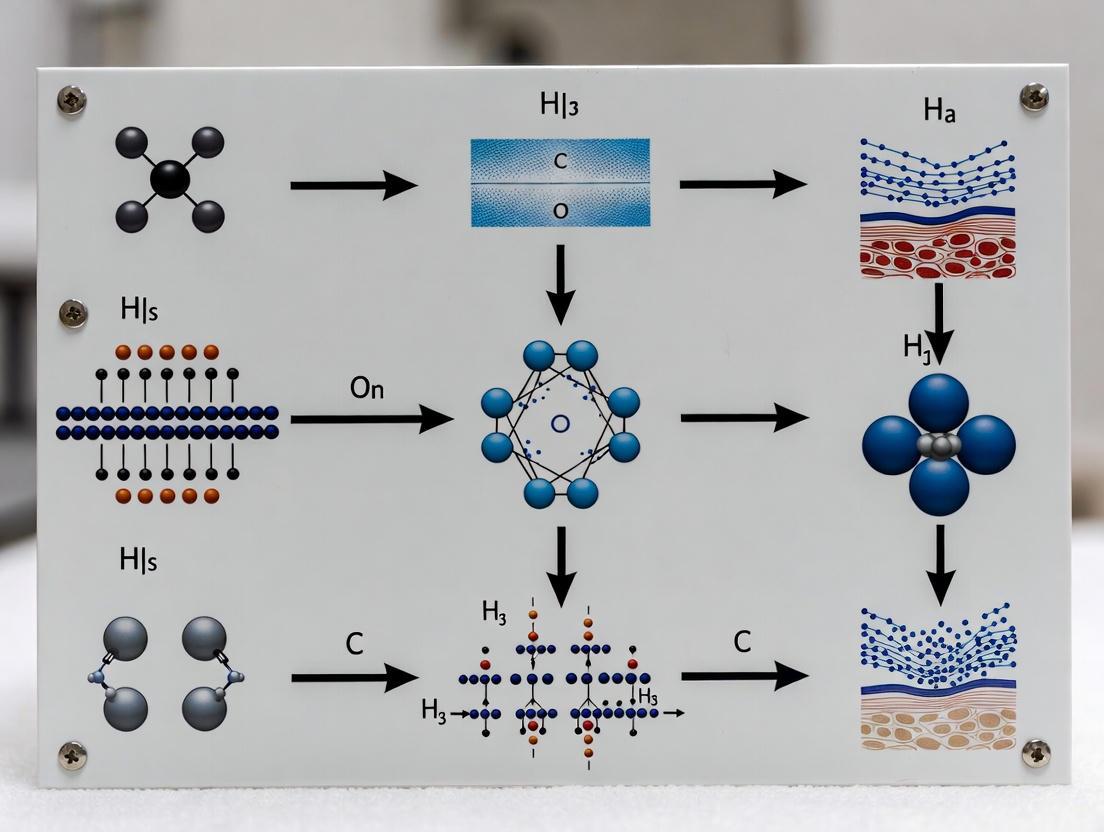

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental interactions and their connections to established biomedical techniques.

Quantitative Parameters and Measurement

Quantifying light-tissue interactions requires precise measurement of specific parameters that characterize each interaction type. The following table summarizes the key quantitative metrics, their definitions, and representative values in biological tissues.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for Light-Tissue Interactions

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Typical Range in Tissue | Primary Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient | µa | Probability of photon absorption per unit path length (mm⁻¹). | 0.01 - 10 mm⁻¹ (varies strongly with wavelength and chromophore) | Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI), Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) [1] |

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient | µs' | Probability of photon scattering per unit path length, adjusted for anisotropy (mm⁻¹). | 1 - 20 mm⁻¹ (NIR region) | Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) [1] |

| Fluorescence Quantum Yield | QY | Ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed. | 0.01 - 0.9 (depends on fluorophore and environment) | Fluorescence Imaging, Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) [1] |

| Fluorescence Lifetime | τ | Average time a fluorophore remains in the excited state before emission (nanoseconds). | 1 - 10 nanoseconds | Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) [1] |

| Thermal Diffusion Length | µ | Distance heat propagates in a material during the laser pulse or modulation period (μm). | Function of modulation frequency and tissue thermal properties [3] | Photoacoustic Sensing [3] |

The thermal diffusion length (µ) is a critical parameter in techniques like photoacoustic sensing, where it is calculated as μ = √(k / (π * ρ * f * c)), where k is thermal conductivity, ρ is density, c is specific heat, and f is the modulation frequency of the light [3].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

This section provides detailed protocols for investigating the fundamental interactions using common biophotonic techniques.

Protocol: Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI) for Absorption Mapping

Photoacoustic Imaging leverages light absorption to generate acoustic waves for deep-tissue imaging. The following workflow details the experimental setup and procedure.

1. Objective: To map the distribution of optical absorbers (e.g., hemoglobin, melanin) in biological samples by detecting ultrasonic waves generated by light absorption.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Pulsed Laser Source: Nd:YAG laser or Ti:Sapphire laser with nanosecond pulse duration, tunable in the visible to NIR range (e.g., 532-1064 nm) [3].

- Ultrasound Transducer: Focused single-element transducer or array transducer with central frequency matched to desired resolution/depth (e.g., 10-50 MHz) [3].

- Data Acquisition System: High-speed digitizer for recording photoacoustic signals.

- 3D Motorized Stage: For raster-scanning the transducer or sample.

- Acoustic Coupling Medium: Ultrasound gel or water for signal transmission.

3. Procedure: 1. Sample Preparation: Place the biological sample (e.g., tissue section, small animal) in the imaging chamber. Ensure proper acoustic coupling between the sample and transducer. 2. System Alignment: Align the laser beam to co-axially overlap with the ultrasound transducer focus. For OR-PAM, focus the laser beam using an objective lens [3]. 3. Data Acquisition: * Set the laser wavelength to target specific chromophores. * Initiate raster scanning over the region of interest. * At each point, the laser fires a pulse. The resulting photoacoustic signal is detected by the transducer, converted to an electrical signal, and recorded by the data acquisition system [3]. 4. Signal Processing: * Apply band-pass filtering to the raw signals to reduce noise. * For each scan point, the amplitude of the detected photoacoustic signal is proportional to the local absorption coefficient [3]. 5. Image Reconstruction: Use a reconstruction algorithm (e.g., back-projection) to convert the time-resolved acoustic signals from all scan points into a 2D or 3D map of optical absorption.

Protocol: Spatial Frequency Domain Imaging (SFDI) for Absorption and Scattering Quantification

1. Objective: To quantitatively map the optical absorption (µa) and reduced scattering (µs') coefficients over a wide field of view by analyzing the demodulation of structured illumination patterns.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Projection System: Digital Light Projector (DLP) or LCD projector.

- Scientific Camera: CCD or CMOS camera with appropriate lens.

- Light Source: Broadband (e.g., halogen) or multiple laser diodes/LEDs.

- Computer: For pattern generation, control, and data analysis.

3. Procedure: 1. Pattern Projection: Project sinusoidal illumination patterns of known spatial frequencies (e.g., 0 mm⁻¹ and 0.2 mm⁻¹) onto the sample surface at multiple phases (typically 0°, 120°, 240°). 2. Image Acquisition: For each pattern frequency and phase, capture a reflected image with the camera. 3. Demodulation: At each pixel, process the three phase-shifted images to compute a demodulated reflectance image, which separates the contribution of the projected pattern from the ambient light. 4. Model Fitting: Use a light transport model (e.g., diffusion approximation or Monte Carlo simulation) to fit the measured reflectance at multiple spatial frequencies, thereby extracting pixel-wise maps of µa and µs'.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in biomedical optics requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for the featured photoacoustic imaging experiment and the broader field.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biophotonics Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Washing and suspending cells (e.g., Red Blood Cells - RBCs) to maintain osmotic balance and physiological pH during preparation for PAI [3]. | Isotonic PBS is used to wash RBCs two times after centrifugation to separate plasma [3]. |

| Acoustic Coupling Gel | Ensures efficient transmission of generated acoustic waves from the sample to the ultrasound transducer in contact PAI modes [3]. | Standard ultrasound gel; water can also be used as a coupling medium in non-contact configurations [3]. |

| Exogenous Contrast Agents | Enhances optical absorption at specific wavelengths to improve signal-to-noise ratio for targeting molecular biomarkers. | Includes organic dyes (e.g., ICG), gold nanoparticles, and carbon nanotubes. |

| Objective Lens | Focuses the excitation laser beam to a small spot size for high-resolution Optical-Resolution PAM (OR-PAM) [3]. | Infinity-corrected objectives (e.g., 40x, 0.25 NA) are used to focus the laser onto the sample [3]. |

| Resonator Column | Amplifies weak, continuous-wave laser-induced photoacoustic signals to detectable levels in specific sensor designs [3]. | The design of the resonator column and sample chamber size critically affects the quality factor and signal amplification [3]. |

Advanced Techniques and Applications

Non-linear optical phenomena have significantly advanced biomedical imaging, enabling greater penetration depth and spatial resolution.

Multi-Photon and Harmonic Generation Microscopy

Multi-photon absorption occurs when a fluorophore simultaneously absorbs two or more longer-wavelength (typically NIR) photons. The combined energy excites the molecule, followed by fluorescence emission.

- Advantages: The use of NIR femtosecond lasers reduces scattering and allows deeper tissue imaging. The excitation is confined to a tiny focal volume, providing inherent optical sectioning and reduced photobleaching outside the focal plane [1].

- Harmonic Generation: Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) and Third Harmonic Generation (THG) are non-linear scattering processes where two or three photons combine to generate a new photon at exactly half or one-third the wavelength, respectively. SHG is particularly useful for visualizing non-centrosymmetric structures like collagen [1].

Coherent Raman Scattering (CRS) Microscopy

Techniques like Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS) and Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) overcome the inherent weakness of spontaneous Raman scattering.

- Principle: These methods use multiple laser beams to coherently drive molecular vibrations, resulting in a signal enhancement of several orders of magnitude compared to linear Raman scattering [1].

- Application: CRS enables high-speed, label-free chemical imaging of biomolecules such as lipids and proteins within living cells and tissues, bypassing the need for fluorescent labels [1].

The fundamental interactions of light—absorption, scattering, and fluorescence—provide the underlying framework for a powerful and expanding suite of tools in biomedical research. The quantitative parameters and detailed experimental protocols outlined in this whitepaper serve as a foundation for researchers developing new diagnostic methods, therapeutic interventions, and drug development platforms. As biophotonics continues to evolve, driven by advancements in lasers, detectors, and artificial intelligence, these core principles will remain essential for unlocking deeper insights into biological processes and disease mechanisms, ultimately paving the way for next-generation precision medicine.

The quantitative measurement of tissue optical properties is a cornerstone of biomedical optics, essential for both therapeutic and diagnostic applications [4]. The manner in which light propagates within and interacts with biological tissues provides critical information on tissue architecture and physiology, which can directly quantify damage or abnormalities [5]. This interaction is primarily governed by two fundamental optical properties: the absorption coefficient (μa) and the reduced scattering coefficient (μs'). These intrinsic parameters determine the measurable transmission and reflection of light, and their accurate estimation is vital for technologies ranging from photodynamic therapy and photocoagulation to non-invasive disease diagnosis and health monitoring [6] [4].

The field has evolved from simple qualitative assessments to sophisticated quantitative methods that leverage computational modeling. The ability to disentangle the effects of absorption and scattering from measured light signals allows researchers to extract meaningful physiological data, such as blood oxygen saturation and tissue composition [7]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core optical properties, their measurement methodologies, and their significance within biomedical research.

Defining the Fundamental Optical Properties

When light is incident on biological tissue, a portion is reflected at the air-tissue interface due to refractive index mismatch. The remaining light penetrates the tissue and undergoes a series of absorption and scattering events, which spatially broaden and attenuate the light before some of it escapes as diffuse reflectance or transmittance [6]. The following parameters are used to quantitatively describe these processes.

Absorption Coefficient (μa)

The absorption coefficient (μa) is defined as the probability of a photon being absorbed per unit pathlength of travel through the medium, with a typical order of magnitude of 0.1 cm⁻¹ in the near-infrared (NIR-I) window [6]. Absorption occurs in tissue chromophores—the light-absorbing molecules within tissue. The total μa is a linear combination of the molar extinction coefficients (ε) for all chromophores present, weighted by their concentrations (C) [6] [8]. This relationship is described by: μa = ln(10) Σ (εi Ci) [8].

The dominant chromophores in blood are oxyhemoglobin (HbO₂) and deoxyhemoglobin (HHb), whose distinct absorption spectra in the visible and NIR wavelengths enable the determination of oxygen saturation [6]. Other significant chromophores include water, lipids, melanin, and collagen [6]. The ratio of oxyhemoglobin concentration to total hemoglobin concentration defines the oxygen saturation (StO₂), a key biomarker in clinical applications such as tissue oxygenation monitoring [6] [9].

Scattering Properties

Scattering in tissue arises from refractive index inhomogeneities, such as variations between subcellular organelles (e.g., nuclei, mitochondria) and their surrounding cytoplasmic medium [6].

- Scattering Coefficient (μs): The scattering coefficient (μs) is defined as the probability of photon scattering per unit pathlength, with a typical order of magnitude of 100 cm⁻¹ in the NIR-I window. The inverse of μs is the scattering mean free path (mfpₛ), which represents the average distance a photon travels between two scattering events [6].

- Anisotropy Factor (g): Scattering in biological tissues is not isotropic but strongly forward-directed. The anisotropy factor (g) is defined as the average cosine of the scattering angle (θ), with values ranging from 0 (perfectly isotropic scattering) to 1 (purely forward scattering). Most biological tissues have a g value of approximately 0.9 [6].

- Reduced Scattering Coefficient (μs'): Given the highly forward-directed nature of scattering, the reduced scattering coefficient (μs') is defined as μs' = μs(1 - g). This parameter represents the probability of equivalent isotropic photon scattering per unit pathlength in the diffusive regime and has a typical order of magnitude of 10 cm⁻¹ in the NIR-I window [6] [9]. The mean free path between effectively isotropic scattering events (mfpₛ') is 1/μs'.

Derived Parameters in Diffusion Theory

When light propagation becomes diffusive after multiple scattering events, several parameters are derived from μa and μs' to characterize the light field, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Characterizing Tissue Optical Properties

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Common Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient | μa | Probability of photon absorption per unit pathlength | cm⁻¹ or mm⁻¹ |

| Scattering Coefficient | μs | Probability of photon scattering per unit pathlength | cm⁻¹ or mm⁻¹ |

| Anisotropy Factor | g | Average cosine of the scattering angle, | Unitless |

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient | μs' | μs' = μs(1 - g) | cm⁻¹ or mm⁻¹ |

| Transport Coefficient | μt' | μt' = μa + μs' | cm⁻¹ or mm⁻¹ |

| Diffusion Coefficient | D | D = [3(μa + μs')]⁻¹ | mm or cm |

| Effective Attenuation Coefficient | μeff | μeff = √(μa / D) = √[3μa(μa + μs')] | cm⁻¹ or mm⁻¹ |

Measurement Techniques and Experimental Protocols

A range of techniques has been developed to measure the optical properties of biological tissues. These methods can be broadly categorized as steady-state (or continuous wave), time-domain, frequency-domain, spatial-domain, and spatial frequency-domain imaging [6]. The experimental measurements are coupled with computational models of light-tissue interactions to inversely solve for μa and μs' from the measured reflectance and/or transmittance [6].

Integrating Sphere Technique

The integrating sphere (IS) is a standard apparatus for measuring total diffuse reflectance and total transmittance, which serve as inputs for inverse models to determine μa and μs' [10] [5].

- Protocol Overview: A thin slice of tissue is illuminated by a collimated beam, and both the diffusely reflected and transmitted light are collected and integrated by the sphere(s) [4]. The inner surface of the sphere is coated with a high-reflectivity material (reflectance > 98%) to uniformly distribute the captured light, which is then detected by a spectrometer [10].

- System Configurations:

- Single Integrating Sphere (SIS): Allows for stepwise measurement of diffuse reflectance and transmittance by alternately positioning the sample at the reflectance or transmittance port. Four ports are typically located at the equatorial plane (0°, 90°, 180°) and the top of the sphere. The 0° port is connected to a light source, while detectors are placed at other ports [10].

- Double Integrating Sphere (DIS): A sample is sandwiched between two spheres, enabling simultaneous measurement of diffuse reflectance (Rd) and transmittance (Td). This configuration, coupled with collimated transmittance (Tc) measurement, provides a more complete data set for inverse analysis, improving the accuracy of extracted optical properties [10].

- Inverse Models: The measured Rd and Td are fed into an inverse model to calculate μa and μs'. Common models include:

- Inverse Adding-Doubling (IAD): An iterative technique where a set of optical properties is guessed, and the corresponding reflection and transmission are calculated using the adding-doubling method. The process repeats until the calculated values match the measured values [10] [11].

- Inverse Monte Carlo (IMC): Uses stochastic simulations of photon propagation to find the optical properties that best reproduce the measured data [10].

- Kubelka-Munk (KM) Model: A simpler, two-flux model that directly relates Rd and Td to the absorption (K) and scattering (S) coefficients. Its parameters are frequently used in medical physics due to its relative simplicity [5].

The workflow for the double integrating sphere method is illustrated below.

Spatially Resolved (SR) and Time-Domain (TD) Techniques

Other prominent methods focus on measuring the spatial or temporal distribution of light.

- Spatially Resolved (SR): This method acquires the radially dependent diffuse reflectance profile, R(ρ), versus the source-detector distance (ρ). The resulting data is then inverted to estimate μa and μs' [10] [9]. In continuous-wave (CW) systems, this approach is the basis for commercial near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) devices that estimate tissue oxygen saturation [9].

- Time-Domain (TD): This technique records the temporal point-spread function, I(t), of diffusely propagating photons following ultrashort pulse illumination. By fitting the temporal distribution of detected light with a model based on diffusion theory or Monte Carlo simulations, μa and μs' can be estimated [10] [9]. This method provides rich data but requires relatively complex instrumentation [10].

- Time-Domain Spatially Resolved (TD-SRS): A hybrid approach extends the SRS methodology to the time domain. It calculates the spatial derivative of the time-dependent attenuation, A(ρ,t), to estimate μs' [9]. This method can assess the spatial homogeneity of scattering in the explored tissue [9].

The logical relationship between the primary measurement methods is summarized in the following diagram.

Quantitative Data of Tissue Optical Properties

The optical properties of tissues vary significantly across tissue types and wavelengths. Table 2 provides representative values for key biological materials in the red and near-infrared (NIR) spectral range, which is often called the "therapeutic window" due to reduced absorption by hemoglobin and water, allowing for deeper light penetration.

Table 2: Representative Optical Properties of Biological Tissues at Near-Infrared Wavelengths

| Tissue / Material | Absorption Coefficient μa (cm⁻¹) | Reduced Scattering Coefficient μs' (cm⁻¹) | Anisotropy Factor (g) | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | Varies with Hb content | ~13 | ~0.99 | Highly dependent on hematocrit, oxygenation; scattering is strongly forward-directed. | [8] |

| Skin | ~0.1 | ~10 - 20 | ~0.9 | Properties vary with hydration; dry skin shows different scattering. | [6] [5] |

| Adipose Fat | Low (dominated by lipids) | Moderate | ~0.9 | Optical parameters change with boiling (structural alteration). | [5] |

| General Tissue (NIR) | ~0.1 | ~10 | ~0.9 | Typical orders of magnitude in the NIR-I window (650-950 nm). | [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in tissue optics requires specific instruments, computational tools, and sample preparation materials. Table 3 details key components of a typical research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Integrating Sphere | A core instrument for measuring total diffuse reflectance and transmittance from tissue samples. The inner wall is coated with a highly reflective material (e.g., Spectralon) to integrate light uniformly. [10] [5] |

| Tissue-Mimicking Phantoms | Reference standards with known and stable optical properties, used for system calibration and validation. Often made from materials like polyurethane or liquid suspensions with calibrated scatterers (e.g., TiO₂, polystyrene microspheres) and absorbers (e.g., India ink, nigrosin). [10] |

| Inverse Adding-Doubling (IAD) Software | A standard computational algorithm for extracting the absorption and reduced scattering coefficients (μa, μs') from integrating sphere measurements (Rd, Td). [10] [11] |

| Monte Carlo Simulation Package | A computational method for modeling the random walk of photons in a scattering medium. It is used as a forward model to predict light transport or as an inverse model (IMC) to extract optical properties. [10] [12] |

| High-Sensitivity Spectrometer | For resolving spectral measurements of diffuse reflectance and transmittance, enabling the decomposition of μa into contributions from individual chromophores. |

| Thin Sample Holder | For preparing and mounting tissue samples of precise, uniform thickness (e.g., 2-3 mm), which is critical for accurate transmission and reflection measurements. [5] |

The absorption coefficient μa and the reduced scattering coefficient μs' are fundamental parameters that quantitatively describe light transport in biological tissues. As detailed in this guide, a suite of well-established techniques, notably integrating sphere measurements coupled with inverse models like IAD, enables their accurate determination. These optical properties are not merely abstract numbers; they provide a window into tissue composition, microstructure, and physiological status.

The field continues to advance with the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning, which enhances the accuracy of inverse models and the robustness of optical property estimation [10]. Furthermore, the development of portable and cost-effective systems is promoting the translation of these techniques from research labs to clinical and point-of-care settings [10] [7]. A deep understanding of these core optical properties and their measurement is, therefore, indispensable for any researcher or professional working in biomedical optics, drug development, and diagnostic technology innovation.

Biomedical optical imaging technologies provide non-invasive methods for diagnosing and monitoring diseases by leveraging the unique ways light interacts with biological tissues. These interactions, which include absorption, scattering, and fluorescence, generate contrast that reveals both structural and functional information about tissue health and composition. The most significant endogenous chromophores—hemoglobin, lipids, and water—each possess distinct absorption profiles across the optical spectrum. Their concentrations and spatial distribution within tissue serve as key indicators of physiological status, signaling conditions such as tumor formation, inflammation, and metabolic disorders. This technical guide details the molecular origins of optical contrast, quantitative concentration ranges found in biological tissues, experimental protocols for measurement, and the advanced imaging technologies that exploit these properties for research and clinical applications. A comprehensive understanding of these principles is fundamental to advancing biomedical optics research and developing new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Table 1: Core Endogenous Chromophores and Their Roles in Optical Contrast.

| Chromophore | Primary Optical Significance | Key Absorption Peaks (nm) | Physiological Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Oxy) | Dominant absorber in NIR window; oxygen delivery | ~540, ~580, ~850 [13] | Blood volume, tissue oxygenation, metabolism |

| Hemoglobin (Deoxy) | Dominant absorber in NIR window; oxygen consumption | ~560, ~760 [14] | Oxygen consumption, hypoxic states |

| Lipids | Major absorber in SWIR; structural and energy storage | ~930, ~1210 [15] | Adipose tissue content, metabolic disease, certain tumors |

| Water | Dominant absorber in SWIR; tissue hydration | ~980, ~1200 [15] | Tissue edema, cystic structures |

Quantitative Chromophore Properties and Tissue Concentrations

Accurate quantification of chromophore concentrations is vital for interpreting optical imaging data. The absorption coefficient of tissue (μₐ) is a linear combination of the concentration of each constituent chromophore multiplied by its specific wavelength-dependent absorption coefficient. This relationship is formalized as μₐ(λ) = Σ cᵢ ∙ εᵢ(λ), where cᵢ is the concentration and εᵢ(λ) is the molar absorption spectrum of the i-th chromophore. The reduced scattering coefficient (μₛ'), which describes how light is scattered in tissue, is often modeled using an approximation to Mie scattering theory: μₛ'(λ) = A ∙ λ^(-SP), where A is a scaling amplitude and SP is the scattering power related to the size and density of scattering particles [16].

The following tables summarize typical concentration ranges for key chromophores in healthy and pathological tissues, providing a critical reference for data interpretation.

Table 2: Typical Chromophore Concentration Ranges in Human Breast Tissue [16].

| Tissue Component | Concentration Range | Notes and Correlations |

|---|---|---|

| Total Hemoglobin (HbT) | 10 - 60 μM | Inversely correlated with body mass index (BMI). |

| Hemoglobin Oxygen Saturation (StO₂) | 0 - 90% | Varies with tissue type and metabolic activity. |

| Water Fraction | 11 - 74% | Higher in glandular tissue, lower in adipose tissue. |

| Lipid Fraction | 26 - 90% | Higher in adipose tissue; average breast is ~81% adipose. |

Table 3: Optical Property Ranges for Biological Tissues (600-1000 nm).

| Optical Property | Typical Range in Tissue | Governed By |

|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient (μₐ) | 0.001 - 0.05 mm⁻¹ | Chromophore concentration and type (Hb, H₂O, lipids) [14] |

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient (μₛ') | 0.5 - 2.0 mm⁻¹ | Density and size of cellular and subcellular structures [16] |

| Scattering Power (SP) | Varies with tissue structure | Higher in fibrous/glandular tissue, lower in fatty tissue [16] |

Experimental Methodologies for Contrast Measurement

Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy for Hemoglobin and Water

Objective: To non-invasively quantify concentrations of oxyhemoglobin (HbO₂), deoxyhemoglobin (HbR), and water (H₂O) in tissue using diffuse optical spectroscopic imaging (DOSI).

Protocol:

- System Setup: Utilize a DOSI system combining frequency-domain and continuous-wave components. The frequency-domain component typically uses laser diodes at multiple wavelengths (e.g., 660-850 nm) modulated at high frequencies (50-600 MHz). The continuous-wave component employs a broadband white light source and a spectrometer to sample a wide spectrum (e.g., 580-1020 nm) [17] [16].

- Data Acquisition: Place the optical probe in gentle contact with the tissue surface. Acquire frequency-domain data to determine the absolute absorption (μₐ) and reduced scattering (μₛ') coefficients at discrete wavelengths. Use these as a baseline to calibrate the hyperspectral continuous-wave data, converting measured diffuse reflectance into accurate μₐ(λ) spectra across all wavelengths [17].

- Spectral Fitting: Perform a linear least-squares fit of the measured absorption spectrum using the known molar absorption spectra of the target chromophores (HbO₂, HbR, H₂O). The fitting model is μₐ(λ) = [εHbO₂(λ)]·[HbO₂] + [εHbR(λ)]·[HbR] + [ε_H₂O(λ)]·[H₂O]. Positivity constraints are applied to ensure non-negative concentrations [14] [16].

- Calculation of Derived Parameters:

- Total Hemoglobin: HbT = [HbO₂] + [HbR]

- Oxygen Saturation: StO₂ = [HbO₂] / HbT × 100%

Shortwave Infrared Meso-Patterned Imaging (SWIR-MPI) for Water and Lipids

Objective: To provide non-contact, label-free spatial mapping of water and lipid concentrations in tissue by exploiting their strong absorption in the shortwave infrared (SWIR) region.

Protocol:

- System Setup: Employ a SWIR-MPI system with a wavelength-tunable pulsed laser (680-1300 nm) and a digital micromirror device (DMD) to project structured illumination patterns (e.g., DC and AC spatial frequencies) onto the tissue. Remitted light is captured by a SWIR-sensitive germanium CMOS camera [15].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire images of the sample under patterned illumination at multiple wavelengths across the SWIR range (900-1300 nm), specifically targeting the absorption peaks of water (~980, ~1200 nm) and lipids (~930, ~1210 nm).

- Inverse Model and Lookup Table (LUT): Demodulate the acquired images to obtain diffuse reflectance at different spatial frequencies for each pixel. Input these values into an inverse model that references a pre-computed LUT generated from Monte Carlo simulations of light transport. The LUT maps the measured reflectance patterns to unique combinations of μₐ and μₛ' [15].

- Chromophore Concentration Mapping: Apply Beer's law to the extracted μₐ spectra on a pixel-by-pixel basis. Fit the spectra using the known extinction coefficients of water and lipids to generate spatial concentration maps. Concentrations are reported as percentages relative to pure water (55.6 M) and pure lipid (0.9 g/ml) [15].

Optimal Wavelength Selection Algorithm

Objective: To systematically select an optimal set of wavelengths for accurate spectral fitting of diffuse reflectance data, improving the stability and precision of chromophore concentration estimates.

Protocol:

- Construct Basis Matrix: Create a wavelength-dependent pathlength-modulated absorption matrix (μaL) for an oversampled set of wavelengths. Each row represents a wavelength, and each column represents a pathlength-modulated absorption spectrum for a specific chromophore (e.g., HbO₂, HbR, H₂O) [14].

- Iterative Wavelength Removal:

- Start with the full oversampled matrix.

- For each row (wavelength), compute a selection metric after its temporary removal.

- Selection Criterion: The optimal metric is the product of all singular values of the matrix (a measure of its overall orthogonality and stability). Maximizing this product, rather than just optimizing the condition number or the smallest singular value, has been shown to yield lower RMS errors in concentration estimates [14].

- Elimination and Iteration: Permanently remove the wavelength whose elimination results in the largest product of singular values. Repeat the process until the desired number of wavelengths is achieved. This algorithm typically identifies robust wavelength combinations, such as 532 nm, 596 nm, and 616 nm for fitting HbO₂, HbR, and H₂O [14].

Diagram 1: Workflow for optimal wavelength selection via singular value maximization.

Visualization of Contrast Origins and Workflows

The diagnostic power of optical imaging stems from the direct relationship between tissue molecular composition and the resulting optical signals. The following diagram illustrates the causal pathway from a tissue's underlying biology to the measurable contrasts used in various imaging modalities.

Diagram 2: The signal pathway from molecular composition to optical contrast.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in biomedical optics relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents for system calibration, phantom validation, and contrast enhancement.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Optical Spectroscopy and Imaging.

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue-Simulating Phantoms | Intralipid emulsion [16], Solid resin phantoms [17] | System validation, calibration, and performance testing. | Tissue-like μₐ and μₛ'; highly repeatable; durable. |

| Anthropomorphic Phantoms | Lard-guar gum matrices [17], Hemoglobin-doped phantoms [17] | Mimicking realistic tissue geometry and composition. | Physiological water:lipid ratios; incorporates Hb; free-standing. |

| Emulsifying Agents | Guar gum, Soy lecithin, Borax [17] | Creating stable, semi-solid phantoms with high lipid content. | Ubiquitous, inexpensive, non-toxic; provides structural scaffolding. |

| Blood & Hemoglobin Sources | Porcine blood [17], Whole human blood [16] | Simulating vascularization and oxygen metabolism in phantoms. | Provides native HbO₂ and HbR; enables StO₂ studies. |

| Scattering Agents | Intralipid [16], Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) [17] | Adjusting the reduced scattering coefficient (μₛ') of phantoms. | Controlled particle size; predictable scattering spectra. |

| Exogenous Contrast Agents | Indocyanine Green (ICG) [18] [19], Targeted nanoparticles [19] | Enhancing contrast for specific molecular targets (e.g., tumors). | High absorption in optical window; biocompatible. |

Theoretical Foundations of Light Propagation in Tissue

The Radiative Transport Equation (RTE) is widely considered the most accurate deterministic model for describing light propagation in scattering and absorbing media like biological tissue. It serves as the fundamental equation for investigating particle transport across various scientific fields, including astrophysics, neutron transport, climate research, and biomedical optics [20]. In the context of medical optics, the RTE provides a valid approximation of Maxwell's equations while avoiding the prohibitive computational costs associated with solving them numerically, making it suitable for applications ranging from microscopic volumes to entire organs [20]. The steady-state form of the RTE is expressed as:

Ω · ∇I(x,Ω) + μ_t(x)I(x,Ω) = μ_s(x)∫_S² f(x,Ω,Ω')I(x,Ω')dΩ' + S(x,Ω)

Where:

I(x,Ω)is the radiance at positionxin directionΩμ_t = μ_a + μ_sis the total attenuation coefficientμ_aandμ_sare the absorption and scattering coefficients, respectivelyf(x,Ω,Ω')is the scattering phase functionS(x,Ω)is the internal source distribution [20]

The RTE is an integro-differential equation that balances gains and losses of photons traveling through a medium. The terms represent, in order: the net change of radiance in a specific direction, losses due to absorption and scattering out of the direction, gains from scattering into the direction from all other directions, and contributions from internal light sources.

The scattering phase function f(x,Ω,Ω') describes the probability of light scattering from direction Ω' to Ω. In biomedical optics, the Henyey-Greenstein phase function is commonly used, though simplified approximate MIE (SAM) phase functions have also been developed to better fit Mie theory for tissue applications [21].

For modeling light propagation at boundaries between different media (such as tissue-air interfaces), the RTE must be solved with appropriate boundary conditions. A common approach uses the Fresnel reflection coefficient:

I(y,Ω) = R_f(-Ω · n̂)I(y,Ω̄) for Ω · n̂ < 0

Where R_f(μ) is the Fresnel reflection coefficient, n̂ is the outward normal vector, and Ω̄ = Ω - 2(n̂ · Ω)n̂ is the reflection of vector Ω on the tangent plane [20].

The Diffusion Approximation to the RTE

The Diffusion Approximation (DA) is a widely used simplification of the RTE that offers computational efficiency while maintaining reasonable accuracy for many biomedical applications. The DA is derived by expressing the radiance and phase function as first-order expansions using spherical harmonics (the P1 approximation), which transforms the RTE into a more tractable form [22].

The time-independent diffusion equation is expressed as:

-∇ · [D(r)∇Φ(r)] + μ_a(r)Φ(r) = S(r)

Where:

Φ(r)is the photon fluence rateD(r) = 1/[3(μ_a + μ_s')]is the diffusion coefficientμ_s' = μ_s(1-g)is the reduced scattering coefficientgis the anisotropy factor [23]

The DA assumes that light propagation is highly scattering-dominated (μs' >> μa) and that the angular distribution of radiance is nearly isotropic. These assumptions make the DA particularly suitable for modeling light propagation in deep tissue regions where photons have undergone many scattering events.

The relationship between the fundamental RTE and its various approximations can be visualized as follows:

Comparative Analysis of RTE and DA

Performance Characteristics and Limitations

The DA provides accurate predictions in scattering-dominated regimes but fails in specific scenarios where its underlying assumptions break down [24]. The RTE offers superior accuracy but at significantly higher computational cost.

Table 1: Comparison of RTE and Diffusion Approximation Characteristics

| Characteristic | Radiative Transport Equation (RTE) | Diffusion Approximation (DA) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Nature | Integro-differential equation | Parabolic partial differential equation |

| Computational Cost | High | Low |

| Accuracy Near Sources/Boundaries | High accuracy | Poor accuracy |

| Accuracy in Low-Scattering Regimes | High accuracy | Fails |

| Accuracy in High-Absorption Regimes | High accuracy | Fails |

| Angular Resolution | Full angular dependence | Limited (cosine + constant) |

| Common Solution Methods | Monte Carlo, Discrete Ordinates, Spherical Harmonics, Finite Element Method | Analytical solutions, Finite Element Method |

Validity Ranges and Application Boundaries

Numerical studies have established specific validity criteria for the diffusion approximation. Research comparing DA with Monte Carlo simulations (considered a gold standard for verification) has demonstrated that DA can be accurately applied when μs' >> μa, even with sensors located very close to sources (>1mm) [25]. However, the accuracy of DA diminishes significantly when the reduced scattering to absorption ratio decreases below a critical threshold.

Table 2: Validity Ranges of Diffusion Approximation Based on Scattering Properties

| Scattering Condition | μs'/μa Ratio | DA Validity | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Scattering | >10-30 | Reliable in deep tissue | Fails near sources/boundaries |

| Moderate Scattering | 1-10 | Limited validity | Inaccurate for small source-detector separations |

| Low Scattering | <1 | Not valid | Cannot predict light distribution |

| Anisotropic Scattering | Any value with high g | Limited validity | Fails to capture directional effects |

The DA is particularly unreliable for predicting angle-resolved radiance because its angular dependence consists only of a cosine plus a constant, which cannot capture the complex angular distributions occurring in tissues [20]. For applications requiring accurate modeling near sources, boundaries, in low-scattering regions, or in tissues with high absorption, the RTE provides substantially better performance.

Advanced Approximation Methods and Hybrid Approaches

Spherical Harmonics (PN) Approximations

PN methods represent a class of approximations between the exact RTE and the simple DA. These methods expand the radiance and phase function in terms of spherical harmonics, with higher values of N providing increased accuracy at the cost of computational complexity. The P1 approximation leads directly to the diffusion equation, while higher-order approximations (P3 and beyond) offer improved accuracy for specific applications [22].

A significant advancement is the δ-PN approximation, which adds a Dirac-δ function to the Legendre polynomial expansion to better model collimated sources and highly forward-scattering media. The δ-P1 approximation, for instance, provides substantially improved predictions for spatially resolved diffuse reflectance at small source-detector separations and for media with moderate or low albedo compared to the standard DA [22].

Hybrid Formulations

Hybrid methods have been developed to leverage the strengths of different modeling approaches while mitigating their weaknesses:

Coupled RTE-DA Models: These approaches partition the computational domain into regions where the RTE is solved (typically near sources and boundaries) and regions where the DA is sufficient (deep in scattering-dominated tissue) [21]. The solutions are coupled at interfaces through appropriate boundary conditions that ensure conservation of energy and phase continuity.

Hybrid PN Methods: This approach converts the RTE into an integral equation and incorporates radiance predictions from classical PN methods. The resulting method enables accurate computation of radiance near boundaries of anisotropically scattering media with computational effort similar to traditional PN methods but with significantly improved accuracy [20].

Neumann-Series RTE: This method formulates the RTE in integral form and expresses the solution as a Neumann series, where successive terms represent successive scattering events. This approach has been extended to incorporate boundary conditions arising from refractive index mismatch, which is crucial for accurate modeling of photon transport in biomedical applications [24].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Numerical Solution of RTE Using Discrete Ordinates and Finite Elements

The following protocol outlines a robust method for numerically solving the RTE using the Discrete Ordinate Method (DOM) with a streamline diffusion modified continuous Galerkin finite element method [26]:

Angular Discretization (Discrete Ordinate Method):

- Select an appropriate angular quadrature scheme (e.g., level symmetric, Lebedev, or product Gaussian quadratures) to discretize the angular domain.

- Apply phase function normalization to preserve conservative properties after angular discretization and reduce numerical oscillations.

- Transform the RTE into a system of coupled partial differential equations (PDEs) using the selected quadrature weights and directions.

Spatial Discretization (Streamline Diffusion FEM):

- Discretize the spatial domain using an unstructured mesh capable of representing complex tissue geometries.

- Apply the streamline diffusion modification to the continuous Galerkin method to suppress numerical oscillations caused by the transport nature of the RTE.

- Implement appropriate boundary conditions, including Fresnel reflections at tissue-air interfaces.

- Solve the resulting system of linear equations using iterative methods suitable for large, sparse systems.

Validation:

- Compare computed solutions with Monte Carlo simulations for standardized geometries and optical properties.

- Verify that photon densities match Monte Carlo predictions within approximately 5% in deeper tissue regions with standard optical properties [26].

The workflow for implementing this numerical approach is shown below:

Protocol for δ-P1 Approximation for Spatially Resolved Diffuse Reflectance

This protocol describes how to implement the δ-P1 approximation for predicting spatially resolved diffuse reflectance, which provides more accurate results than the standard DA, particularly at small source-detector separations [22]:

Medium Characterization:

- Determine the optical properties of the medium: absorption coefficient (μa), scattering coefficient (μs), and anisotropy factor (g_1).

- Calculate the modified properties for the δ-P1 approximation:

f = g_1²g* = g_1/(1 + g_1)μ_s* = μ_s(1 - f)μ_t* = μ_a + μ_s*

Solution of the δ-P1 Equations:

- Implement the analytical solution for the δ-P1 approximation in a semi-infinite geometry with a pencil beam source.

- Apply the appropriate extrapolated boundary condition for a semi-infinite turbid medium.

- Compute the spatially resolved diffuse reflectance using the closed-form expressions.

Inverse Problem for Optical Property Recovery:

- Develop a multi-stage nonlinear optimization algorithm to recover μa, μs', and g_1 from experimental measurements of spatially resolved diffuse reflectance.

- Minimize the difference between measured reflectance and predictions from the δ-P1 model.

- Validate recovered optical properties against known values from phantoms.

This approach has been demonstrated to recover μa, μs', and g1 with errors within ±22%, ±18%, and ±17%, respectively, for both intralipid-based and siloxane-based tissue phantoms across the optical property range 4 < (μs'/μ_a) < 117 [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Methods and Their Applications in Radiative Transport

| Method/Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Stochastic modeling of photon transport | Gold standard for validation; complex geometries |

| Discrete Ordinate Method (DOM) | Angular discretization of RTE | Numerical solution of RTE in complex domains |

| Spherical Harmonics (PN) | Angular expansion of radiance | Higher-order approximations to RTE |

| Finite Element Method (FEM) | Spatial discretization of PDEs | Handling complex tissue geometries and boundaries |

| δ-PN Approximations | Improved modeling of collimated sources | Media with high anisotropy and small source-detector separations |

| Neumann-Series RTE | Integral formulation of RTE | Accurate modeling of boundary reflections |

| Hybrid RTE-DA Models | Coupling of different models | Large domains with both high and low scattering regions |

| Simplified Approximate MIE (SAM) Phase Function | Approximation of Mie scattering | More accurate scattering models for tissue |

These computational tools enable researchers to select appropriate modeling strategies based on their specific application requirements, balancing accuracy, computational resources, and implementation complexity. The choice of method depends on factors such as the tissue optical properties, source-detector separation, geometric complexity, and required output (e.g., fluence rate, radiance, or reflectance).

Near-infrared (NIR) light, occupying the spectral region from approximately 700 nm to 1700 nm, represents a critical optical window for biomedical applications. Within this range, light experiences minimized scattering, absorption, and autofluorescence in biological tissues, enabling deeper penetration and higher fidelity imaging and spectroscopy [27] [28]. This technical guide delineates the fundamental principles, current methodologies, and applications of NIR light in biomedical optics research, providing a framework for scientists and drug development professionals. The content is structured around the core NIR spectral divisions—NIR-I (700–900 nm) and NIR-II (1000–1700 nm)—and their respective roles in advancing non-invasive diagnostics, metabolic monitoring, and image-guided interventions.

Fundamental Principles of the Near-Infrared Window

The utility of the NIR window in biomedicine is governed by the interplay between light and tissue constituents. Key chromophores such as hemoglobin, water, and lipids exhibit distinct but manageable absorption profiles within the NIR range, allowing sufficient photon transmission for sensing and imaging. The reduced scattering coefficient relative to visible light facilitates penetration depths of several centimeters, a prerequisite for probing deep-tissue structures [27]. Furthermore, the NIR-II sub-window (1000–1350 nm) offers superior performance over NIR-I due to a more pronounced reduction in scattering and minimal autofluorescence, yielding enhanced spatial resolution and signal-to-background ratios for in vivo imaging [27].

Table 1: Characteristics of Near-Infrared Spectral Windows

| Parameter | NIR-I (700–900 nm) | NIR-II (1000–1700 nm) | NIR-IIa (1000–1350 nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penetration Depth | < 1 cm | Up to several centimeters | Optimal for deep-tissue imaging |

| Scattering | Moderate | Significantly Reduced | Minimized |

| Autofluorescence | Present | Negligible | Very Low |

| Water Absorption | Low | Moderate | Low (relative to 1350-1600 nm) |

| Key Applications | fNIRS, ICG imaging (clinical) | NIR-II fluorescence imaging, vascular mapping | High-resolution deep-tissue bioimaging |

NIR Spectroscopy for Metabolic and Disease Monitoring

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a non-invasive, non-ionizing analytical technique that leverages the NIR window to quantify tissue composition and function.

Broadband NIRS for Cerebral Metabolism

Broadband NIRS (bNIRS) extends beyond conventional continuous-wave systems by employing a broad spectrum of light (typically 600-1000 nm) to resolve the concentration changes of cytochrome-c-oxidase (CCO), a key marker of mitochondrial metabolism and cellular energy status [29]. Despite its clinical potential, bNIRS adoption has been limited by instrumental complexity, cost, and size. Recent hardware developments cataloged over the past 37 years show a dominance of quartz tungsten halogen lamps and bench-top spectrometers, with a trend toward miniaturization using fiber optics and compact charge-coupled device sensors [29]. No fully commercial, portable bNIRS device currently exists, though micro form-factor spectrometers are paving the way for wearable designs [29].

Experimental Protocol for bNIRS Measurement of CCO:

- Instrument Setup: A typical system configuration involves a broadband light source (e.g., a quartz tungsten halogen lamp) and a spectrometer with a detection range of 600-1000 nm. Light is delivered to the scalp via a fiber-optic bundle.

- Data Acquisition: The diffusely reflected light is collected by a detector fiber and analyzed by the spectrometer, recording hundreds of wavelengths at each time sample.

- Spectral Analysis: Chromophore concentrations (oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and oxidized CCO) are determined using spectroscopic algorithms, such as the UCLn algorithm, which employs a linear regression fit to the measured changes in optical density across the spectrum.

- Validation: Measurements are often validated against magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), considered a benchmark for assessing cerebral metabolism [29].

NIRS in Conjunction with Machine Learning for Diagnostic Screening

NIRS, combined with machine learning (ML), presents a rapid, non-destructive alternative to traditional diagnostic methods like PCR. A proof-of-concept study for Hepatitis C virus (HCV) detection in serum samples utilized NIRS in the 1000–2500 nm range [30]. L1-regularized Logistic Regression identified informative wavelengths, which were then integrated with routine clinical markers (e.g., GPT, GOT, GGT) using a Random Forest model, achieving an accuracy of 72.2% and an AUC-ROC of 0.850 [30]. This highlights the potential of NIRS-ML integration for scalable, non-invasive early detection and risk assessment.

NIR Fluorescence Imaging

Fluorescence imaging in the NIR windows, particularly the NIR-II, has revolutionized pre-clinical in vivo visualization by providing deep-tissue penetration and high spatial resolution.

NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging with Organic Fluorophores

NIR-II fluorescence imaging (1000–1700 nm) is a focal point in tumor imaging due to its low scattering, weak autofluorescence, and high spatiotemporal resolution [27]. Organic small-molecule fluorophores are prominent owing to their superior biocompatibility, tunable optical properties, and predictable pharmacokinetics. Key structural archetypes include:

- Donor-Acceptor-Donor (D-A-D) frameworks: Featuring strong electron-withdrawing cores like benzobisthiadiazole (BBTD) for long-wavelength emission and high photostability [27].

- Cyanine derivatives: Characterized by a polymethine chain conjugated to terminal heterocycles [27].

- BODIPY and xanthene dyes: Noted for their excellent fluorescence quantum yields [27].

A significant clinical milestone was achieved in 2020, where NIR-II fluorescence-guided surgery using Indocyanine Green (ICG) was successfully performed on patients with liver cancer [27].

Table 2: Selected NIR-II Organic Small-Molecule Fluorophores and Properties

| Fluorophore Class | Example Acceptor/Structure | Emission Range (nm) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-A-D | Benzobisthiadiazole (BBTD) | 1000–1400 | High photostability, tunable emission |

| Cyanine | IR-1061 | 1000–1300 | High molar absorptivity |

| BODIPY | BODIPY FL | 1000–1200 | High quantum yield |

| Xanthene | Si-rhodamine | 1000–1100 | Excellent biocompatibility |

Experimental Protocol for NIR-II Tumor Imaging:

- Probe Administration: The NIR-II fluorophore (e.g., ICG or a targeted organic small-molecule) is intravenously injected into the animal model or patient.

- Image Acquisition: At the appropriate time post-injection (to allow for background clearance and target accumulation), the subject is imaged using a NIR-II imaging system. This typically involves a NIR-II laser for excitation and an InGaAs camera for detection.

- Data Analysis: The acquired images are processed to quantify fluorescence intensity, determine tumor-to-background ratios, and delineate tumor margins.

- Guided Intervention: In surgical applications, the real-time NIR-II video feed assists in locating tumors and identifying critical vasculature [27] [28].

Advanced Microscopy Techniques

The evolution of optical sectioning microscopy techniques, such as light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) and confocal/multiphoton microscopy adapted for the NIR-II window, has enabled high-resolution, volumetric imaging of living specimens with low phototoxicity [31] [28]. These methods are crucial for analyzing complex biological structures and functions within the brain and other organs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for NIR Biomedical Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | Clinically approved NIR-I/NIR-II fluorophore for angiography and image-guided surgery. | FDA-approved; used in clinical NIR-II guided microsurgery [28]. |

| Organic D-A-D Fluorophores | NIR-II imaging probes with tunable emission and good biocompatibility. | BBTD-based fluorophores; design focuses on reducing non-radiative decay [27]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | NIR fluorophore investigated for intraoperative navigation of gastric tumors. | Shows specific uptake by gastric epithelial and cancer cells [28]. |

| Quartz Tungsten Halogen Lamp | High-intensity broadband light source for bNIRS systems. | Dominant source in bNIRS developments [29]. |

| InGaAs Camera | Detection of NIR-II fluorescence (1000-1700 nm). | Essential for NIR-II imaging systems [27]. |

| Bench-top Spectrometer | Disperses and detects broadband light for bNIRS. | Common in laboratory systems; trend toward miniaturization [29]. |

| Fiber Optics | Light delivery and collection for spectroscopy and imaging. | Enables flexible probe design for clinical and pre-clinical use [29] [32]. |

| Targeted Molecular Probes | Fluorophores conjugated to targeting moieties (e.g., aptamers) for specific molecular imaging. | e.g., PD-L1 aptamer-anchored nanoparticles for imaging immune checkpoint expression [28]. |

The near-infrared spectral window provides an indispensable gateway for non-invasive optical interrogation of biological tissues. From monitoring cerebral metabolism with bNIRS to achieving high-resolution tumor visualization with NIR-II fluorophores, the applications are expanding rapidly. Future directions will focus on the miniaturization of hardware, the development of brighter and more specific contrast agents, and the deeper integration of multimodal data with machine learning algorithms. These advancements promise to further solidify the role of NIR optics in both basic biomedical research and clinical translation, ultimately enhancing diagnostic capabilities and therapeutic outcomes.

Biomedical Optical Imaging and Sensing: From Microscopy to Clinical Translation

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive, label-free imaging technique that generates cross-sectional, micrometer-scale images of biological tissues using the backscattering properties of light [33]. First developed in 1991, OCT functions as the "optical equivalent of ultrasound" [34] [35], using near-infrared light waves instead of sound to create interferometric images. The core principle relies on low-coherence interferometry, where light from a broadband source is split into two paths: one directed toward the sample and the other toward a reference mirror [34]. The backscattered light from the sample is recombined with the reference light, and the resulting interference pattern is detected and analyzed to construct depth-resolved images [33]. This method allows for high-resolution visualization of tissue microstructure without the need for tissue excision or contrasting agents, making it particularly valuable for imaging delicate structures and dynamic processes.

The fundamental output of an OCT system is an A-scan (amplitude scan), which represents a single depth profile of reflectivity at one lateral position. A series of adjacent A-scans creates a B-scan (brightness scan), a two-dimensional cross-sectional image. Finally, multiple B-scans form a three-dimensional volumetric data set [34] [35]. A key advantage of OCT is its resolution, which typically ranges from 1-10 microns axially, bridging a critical gap between high-resolution (but shallow-penetrating) microscopy and deep-penetrating (but low-resolution) clinical imaging modalities like MRI and ultrasound [33]. This unique combination of capabilities has established OCT as an indispensable tool in biomedical optics research and clinical diagnostics.

Technical Implementations and System Architectures

Since its inception, OCT technology has evolved through several distinct generations, each offering improvements in speed, sensitivity, and image quality. The table below summarizes the key specifications of the primary OCT implementations.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Major OCT Modalities

| Parameter | Time-Domain OCT (TD-OCT) | Spectral-Domain OCT (SD-OCT) | Swept-Source OCT (SS-OCT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Mechanically scans reference mirror depth; detects interference with a point detector [34] [35] | Uses spectrometer with fixed reference mirror; acquires entire depth profile simultaneously [34] [35] | Uses wavelength-sweeping laser and single detector; acquires spectral interferogram sequentially [34] [35] |

| Scanning Speed | ~400 A-scans/second [35] | 27,000-70,000 A-scans/second [35] | 100,000-400,000 A-scans/second [35] |

| Axial Resolution | ~10 µm [35] | 5-7 µm [35] | ~5 µm [35] |

| Light Source | Superluminescent Diode (810 nm) [35] | Broadband Superluminescent Diode (840 nm) [35] | Swept-Source Tunable Laser (1050 nm) [35] |

| Primary Clinical Use | Early retinal imaging [35] | Standard retinal and anterior segment imaging [35] | Deep tissue imaging (e.g., choroid) [35] |

Fourier-Domain OCT (FD-OCT), which includes both SD-OCT and SS-OCT, represents the current standard for most applications. It offers a significant sensitivity and speed advantage over TD-OCT because it measures the interference spectrum as a function of wavelength, capturing the entire depth information in a single exposure without the need for mechanical scanning of the reference arm [34] [33]. This allows for dramatically faster image acquisition, which reduces motion artifacts and enables more complex volumetric imaging.

Optical Coherence Microscopy (OCM) is a high-resolution variant that combines the coherence gating of OCT with the confocal gating of a scanning microscope [33]. By using high-numerical-aperture objectives, OCM achieves superior lateral resolution, typically around 1-2 µm, which is suitable for visualizing individual cells. Full-Field OCT (FF-OCT) is another specialized implementation that employs a Linnik interferometer configuration with a broadband thermal light source and a 2D camera to capture en face images without the need for lateral scanning [36] [37]. This allows for high transverse resolution and simultaneous parallel detection of all points in the field of view, making it ideal for rapid, single-cell level morphological imaging, such as monitoring apoptosis and necrosis [36] [37].

Advanced Functional and Contrast-Enhanced Extensions

The basic structural imaging capabilities of OCT have been successfully extended to several functional modalities, providing insights into physiology, biomechanics, and molecular composition.

OCT Angiography (OCTA): This functional extension visualizes blood flow by detecting motion contrast from circulating erythrocytes. By comparing the decorrelation signal between multiple rapidly acquired B-scans at the same location, OCTA can generate detailed, depth-resolved maps of the retinal and choroidal vasculature without the need for exogenous dye injection [38] [39] [35]. It has enabled the visualization of previously inaccessible capillary networks, including the radial peripapillary capillaries and the intermediate and deep capillary plexuses in the retina [38].

Doppler OCT (D-OCT): This technique measures the Doppler frequency shift of backscattered light to quantitatively assess blood flow velocity [38] [33]. It is particularly useful for evaluating hemodynamics in larger vessels, though its sensitivity is angle-dependent.

Polarization-Sensitive OCT (PS-OCT): PS-OCT measures the birefringence of tissues, which is altered in structures like collagen and nerve fiber bundles [33]. This provides contrast based on the tissue's microstructural arrangement and is valuable for assessing conditions like glaucoma or corneal scarring.

Contrast-Enhanced OCT with Nanoparticles: To overcome the limited molecular contrast of conventional OCT, researchers have developed exogenous agents such as large gold nanorods (LGNRs). These agents exhibit a strong scattering cross-section and can be detected with picomolar sensitivity using specialized spectral detection algorithms, a method known as MOZART [40]. This allows for functional molecular imaging in vivo, such as mapping tumor microvasculature and lymphatic drainage patterns [40].

Table 2: Functional OCT Extension Modalities

| Technique | Measured Parameter | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT Angiography (OCTA) | Motion contrast/decorrelation from blood flow [38] [35] | Mapping microvascular networks in retina, brain, skin [38] [39] | Non-invasive, depth-resolved visualization of capillaries without dyes |

| Doppler OCT (D-OCT) | Phase shift from moving scatterers [38] [33] | Quantitative blood flow velocity measurement [38] | Provides quantitative flow data |

| Polarization-Sensitive OCT (PS-OCT) | Tissue birefringence [33] | Imaging collagen, nerve fibers, muscle [33] | Contrast based on tissue micro-architecture |

| Contrast-Enhanced OCT | Spectral signal from nanoparticles (e.g., LGNRs) [40] | Molecular imaging, targeted contrast [40] | Enables molecular specificity in OCT |

Experimental Protocols for High-Resolution Cellular Imaging

This section provides a detailed methodology for employing Full-Field OCT (FF-OCT) to monitor drug-induced morphological changes at the single-cell level, as exemplified by a 2025 study investigating apoptosis and necrosis [36] [37].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for FF-OCT Cell Death Imaging

| Item | Specification/Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line | HeLa cells (human cervical cancer cells) [37] | A standard, well-characterized model system for in vitro studies. |

| Culture Medium | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) [37] | Provides nutrients and environment for cell growth and maintenance. |

| Apoptosis Inducer | Doxorubicin (5 μmol/L final concentration) [37] | Chemotherapeutic agent; intercalates into DNA, inducing programmed cell death. |

| Necrosis Inducer | Ethanol (99%) [37] | Causes nonspecific, rapid damage to cell membrane and proteins, inducing unregulated cell death. |

| Custom FF-OCT System | Time-domain Linnik interferometer with halogen light source (650 nm center wavelength) [37] | Enables label-free, high-resolution 3D imaging of cellular morphological dynamics. |

Sample Preparation and Imaging Workflow

- Cell Culture and Seeding: HeLa cells are maintained as a monolayer in DMEM under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). For experiments, cells are seeded onto appropriate imaging dishes and allowed to adhere and proliferate to the desired confluence [37].

- Induction of Cell Death:

- Apoptosis Group: Replace the medium with DMEM containing 5 μmol/L doxorubicin. Doxorubicin triggers apoptosis by causing DNA double-strand breaks and increasing intracellular reactive oxygen species [37].

- Necrosis Group: Replace the medium with DMEM containing 99% ethanol. Ethanol rapidly disrupts the phospholipid bilayer and denatures intracellular proteins, leading to loss of homeostasis and necrotic death [37].

- FF-OCT Image Acquisition:

- Transfer the culture dish to the stage of the custom-built FF-OCT system.

- The system utilizes a broadband halogen light source and identical 40x water-immersion objectives in a Linnik configuration to achieve sub-micrometer resolution [37].

- Imaging is initiated immediately after drug administration. The precision linear stage controls the optical path length to position the coherence gate at specific cellular depths.

- A CCD camera detects the 2D interference images. Phase-shifting via a piezoelectric actuator on the reference mirror is used to isolate the sample's reflection information [37].

- To monitor dynamics, images are captured continuously at 20-minute intervals for up to 180 minutes. At each time point, a z-stack of en face images is acquired to enable 3D reconstruction and surface topography mapping [37].

- Data Processing and 3D Analysis:

- The depth of maximum intensity for each pixel in the A-scan is identified as the cell surface.

- These positions are mapped across the xy-plane to generate a 3D point cloud.

- Spline interpolation is applied to reconstruct and analyze the volume and surface morphology of the cell structures [37].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key experimental and imaging process.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for single-cell death imaging via FF-OCT.

Expected Morphological Outcomes

- Apoptotic Cells: Display characteristic, controlled changes including cell contraction, echinoid spine formation, membrane blebbing, and reorganization of filopodia [36] [37].

- Necrotic Cells: Exhibit rapid and disruptive events such as immediate membrane rupture, leakage of intracellular contents, and an abrupt loss of adhesion structures [36] [37].

FF-OCT-based interference reflection microscopy (IRM)-like imaging effectively highlights the changes in cell-substrate adhesion and boundary integrity throughout these processes [36].

Applications in Biomedical Research and Clinical Translation

OCT and OCM have established profound utility across a wide spectrum of biomedical fields, from basic research to clinical diagnostics and therapeutic monitoring.

In ophthalmology, OCT is the standard of care for diagnosing and managing retinal diseases. It provides critical structural information for conditions like macular holes, epiretinal membranes, age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma [34] [39] [35]. The integration of OCT with scanning laser ophthalmoscopy allows for precise motion tracking and the ability to re-scan the exact same retinal location during follow-up visits, enabling meticulous therapy control [34]. Furthermore, the segmentation of retinal layers provides objective, quantitative biomarkers, such as the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer for glaucoma diagnosis [34] [35].

In neuroscience and neurology, OCT is used for both basic research and clinical applications. In rodent models, it enables in vivo, label-free imaging of the cerebral cortex and microvasculature at high resolution [33]. Clinically, retinal imaging with OCT serves as a window to the brain. Since the retina is an extension of the central nervous system, thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer, as measured by OCT, can serve as a biomarker for the progression of neurodegenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease [33].

In oncology and drug development, the high-resolution morphological imaging capabilities of OCT and FF-OCT are invaluable. As demonstrated in the experimental protocol, FF-OCT can distinguish between different modes of cell death (apoptosis vs. necrosis) in response to chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., doxorubicin) or toxic insults [36] [37]. This provides a powerful, label-free platform for drug toxicity testing and anti-cancer therapy evaluation in vitro. The development of contrast-enhanced OCT with targeted nanoparticles (MOZART) further opens the door to molecular imaging of tumor vasculature and specific biomarkers in vivo [40].

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of OCT's signal generation and processing.

Diagram 2: Core principle of OCT signal generation via interferometry.

Recent innovations continue to expand OCT's capabilities. Visible-light OCT enables high-resolution structural imaging combined with retinal oximetry [39]. Optoretinography (ORG) detects stimulus-evoked intrinsic optical signals from photoreceptors, potentially replacing electroretinography for objective functional assessment [39]. Furthermore, efforts in portable and accessible OCT design aim to decentralize this technology, bringing it into community clinics for wider screening and remote surveillance of chronic diseases [41]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning for automated analysis of OCT images is also becoming widespread, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and providing human-level performance in detecting conditions like glaucoma [39].

Functional and molecular imaging represents a paradigm shift in biomedical optics, enabling researchers to visualize not only anatomical structure but also physiological activity and molecular-level processes. Within this domain, Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) has evolved from a purely structural imaging technique to a versatile platform for functional assessment. The integration of Doppler principles with OCT has unlocked capabilities for quantifying flow dynamics, while OCT angiography (OCTA) has revolutionized microvascular imaging. Concurrently, the development of advanced molecular probes has created pathways for targeted molecular imaging, opening new frontiers in drug development and basic research. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of these technologies within the broader context of biomedical optics research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for their implementation.

Core Principles of Doppler OCT

Doppler OCT is a functional extension of OCT that enables quantification of particle flow speed with high spatial resolution and sensitivity alongside structural imaging [42]. First demonstrated in 1997, Doppler OCT fundamentally relies on the Doppler principle, where the frequency of backscattered light from moving particles undergoes a shift proportional to their velocity [42] [43].

Fundamental Doppler Physics

The Doppler frequency shift (Δf) is calculated using the wave vectors of incoming (kᵢ) and scattered (kₛ) light, and the velocity vector (V) of moving particles [42]:

Δf = (1/2π)(kₛ - kᵢ) · V

When considering the Doppler angle θ (between incident light beam and flow direction), this equation simplifies to:

Δf = (2 · n · V · cos(θ))/λ

where n is the tissue refractive index and λ is the central wavelength of the light source [42]. This relationship forms the foundation for all Doppler OCT velocity measurements.

Evolution of Doppler OCT Methods

The development of Fourier-domain OCT significantly enhanced imaging speed and paved the way for more sophisticated Doppler techniques [42]. The table below summarizes the key methodological developments in Doppler OCT:

Table 1: Evolution of Doppler OCT Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrogram Analysis | Short-time FFT or wavelet transformation to extract Doppler shift from power spectrum [42] | Simultaneous structural and velocity imaging [42] | Compromised velocity sensitivity with increased spatial resolution/speed [42] |