Beyond the Wrist: Evaluating Wearable Optical Sensor Accuracy Against Clinical Gold Standards in Biomedical Research

This article provides a critical analysis of the accuracy and reliability of wearable optical sensors when benchmarked against established clinical gold standards.

Beyond the Wrist: Evaluating Wearable Optical Sensor Accuracy Against Clinical Gold Standards in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a critical analysis of the accuracy and reliability of wearable optical sensors when benchmarked against established clinical gold standards. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational technology of sensors like photoplethysmography (PPG), examines methodological challenges in data acquisition and analysis, outlines prevalent accuracy limitations and optimization strategies, and reviews validation frameworks and comparative performance metrics. The scope encompasses applications from remote patient monitoring to clinical trials, addressing both current capabilities and the path toward regulatory-grade acceptance.

The Science of Light: How Wearable Optical Sensors Work and Their Core Applications

Fundamental Principles of Photoplethysmography (PPG) and Optical Sensing

Photoplethysmography (PPG) is an optical sensing technique that measures blood volume changes in the microvascular bed of tissue. PPG functions by emitting light into the skin and measuring the amount of light reflected or transmitted to a photodetector [1]. As blood volume in the vessels changes with each cardiac cycle, light absorption varies, creating a pulsatile waveform known as the PPG signal. The increasing integration of PPG into consumer wearables has sparked critical research evaluating its accuracy against clinical-grade monitoring systems, forming a crucial thesis in modern digital health validation [1] [2].

This technology fundamentally differs from electrocardiography (ECG), which measures the heart's electrical activity directly. While ECG provides precise R-R intervals for heart rate variability (HRV) analysis, PPG estimates these intervals from peripheral blood volume changes, a metric sometimes termed pulse rate variability (PRV) [3] [4]. This distinction is central to understanding the performance characteristics and appropriate applications of PPG-based monitoring.

Fundamental Principles and Signal Acquisition

Core Operating Mechanism

The PPG system relies on a simple yet effective physical principle: the interaction of light with biological tissue. A typical PPG sensor contains a light-emitting diode (LED) that shines light (often green, though infrared and red are also used) onto the skin, and an adjacent photodetector that measures the intensity of the reflected light [1]. The resulting signal contains two primary components:

- AC Component: A pulsatile waveform synchronous with the cardiac cycle, caused by changes in arterial blood volume.

- DC Component: A relatively constant baseline related to light absorbed by non-pulsatile arterial blood, venous blood, and other tissues.

The AC component, typically representing only 1-2% of the total signal, provides the primary data for cardiovascular parameter estimation [1].

From Raw Signal to Physiological Parameters

The journey from raw PPG signal to clinically relevant metrics involves sophisticated signal processing. The raw signal is susceptible to various artifacts, particularly from motion and ambient light, requiring robust filtering algorithms. Once cleaned, the pulsatile characteristics are analyzed to extract specific features including pulse rate, pulse rate variability, and respiratory rate, with advanced algorithms further enabling detection of conditions like atrial fibrillation [5].

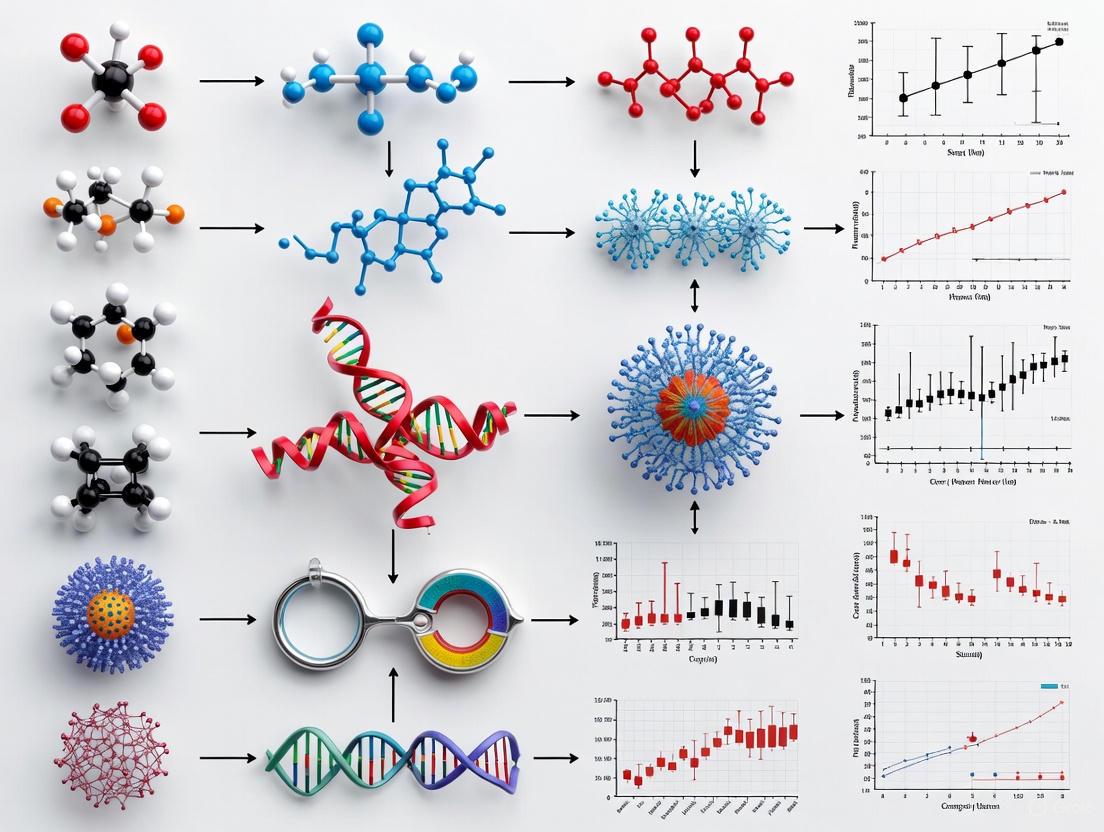

The following diagram illustrates the complete PPG signal processing workflow from acquisition to parameter extraction:

Diagram: PPG Signal Processing Workflow. The pathway illustrates the transformation of raw optical measurements into clinically useful parameters through multiple processing stages.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: PPG Versus Gold Standards

Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability Measurement

PPG demonstrates strong performance in measuring heart rate (HR) under controlled conditions, though its accuracy is influenced by multiple factors. At rest, wearables show mean absolute errors of approximately 2 beats per minute (bpm) with correlations to ECG ranging from moderate to excellent [1]. For heart rate variability (HRV), recent comparative studies reveal more nuanced performance characteristics.

Table 1: PPG vs. ECG for Heart Rate Variability Measurement [3] [4]

| Measurement Condition | HRV Parameter | Reliability (ICC) | Mean Bias | Limits of Agreement | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supine Position | RMSSD | 0.955 (Excellent) | -2.1 ms | Narrow | High agreement with ECG gold standard |

| SDNN | 0.980 (Excellent) | -5.3 ms | Narrow | High agreement with ECG gold standard | |

| Seated Position | RMSSD | 0.834 (Good) | -8.1 ms | Wider | Reduced agreement in seated posture |

| SDNN | 0.921 (Excellent) | -6.2 ms | Wider | Maintained good agreement | |

| Aged >40 Years | RMSSD/SDNN | Reduced Agreement | N/A | Wider | Age impacts signal reliability |

| Female Participants | RMSSD/SDNN | Reduced Agreement | N/A | Wider | Sex influences measurement consistency |

Atrial Fibrillation Detection

For arrhythmia detection, particularly atrial fibrillation (AF), PPG-based smartwatches and ECG-based patches both show excellent diagnostic performance in meta-analyses, though with distinct strengths.

Table 2: Atrial Fibrillation Detection Accuracy [6] [7]

| Device Type | Pooled Sensitivity (%) | 95% Confidence Interval | Pooled Specificity (%) | 95% Confidence Interval | Heterogeneity (I²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPG Smartwatches | 97.4 | 96.5–98.3 | 96.6 | 94.9–98.3 | 3.16% (Sensitivity) 75.94% (Specificity) |

| ECG Smart Chest Patches | 96.1 | 91.3–100.8 | 97.5 | 94.7–100.2 | 94.59% (Sensitivity) 79.1% (Specificity) |

Advanced PPG algorithms have further demonstrated robust AF burden tracking capabilities, with one model showing a correlation coefficient (rₛ) of 0.8788 for AF episode duration proportion and sensitivity of 91.5% compared to Holter monitoring [5].

Specialized Population Applications

PPG validation extends to pediatric populations, where unique physiological and behavioral characteristics present distinct challenges. In a study of children with congenital heart disease or suspected arrhythmias, the Corsano CardioWatch demonstrated 84.8% accuracy for HR measurement compared to Holter monitoring, with good agreement (bias: -1.4 BPM) [8]. Accuracy was notably higher at lower heart rates (90.9% vs 79% at high HR) and declined during intense movement, highlighting the impact of activity level on measurement reliability [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comparative Validation Study Design

Rigorous validation of PPG performance against gold standard references follows standardized experimental protocols:

Participant Selection and Preparation

- Recruitment of healthy adults across age groups (typically 18-70 years) without known cardiovascular conditions [3] [4]

- Exclusion criteria include medications affecting cardiovascular function, smoking, and pregnancy

- Controlled for skin phototype (Fitzpatrick I-III) due to known PPG signal variation with pigmentation [3] [4]

- Stabilization period of 1 minute before formal data collection to establish baseline physiology

Device Configuration and Synchronization

- Simultaneous data collection from PPG and ECG devices with time synchronization

- PPG sensors typically worn on non-dominant arm (e.g., Polar OH1) to minimize motion artifact [3]

- ECG chest straps (e.g., Polar H10) positioned according to manufacturer specifications [3] [4]

- Raw data acquisition enabled via manufacturer SDKs for signal-level analysis

Testing Conditions and Variables

- Body position systematically varied (supine vs. seated) using standardized surfaces

- Measurement durations compared (2-minute vs. 5-minute recordings) per HRV guidelines

- Environmental controls: quiet, dark rooms to minimize sensory interference

- Instruction to participants: relax, breathe normally, keep eyes closed

Signal Processing and Data Analysis

Data Acquisition

- PPG sensors collect peak-to-peak intervals (PPI) for pulse rate variability [3]

- ECG devices record R-R intervals for heart rate variability [3] [4]

- Sampling rates typically ≥100 Hz to ensure sufficient temporal resolution

Signal Preprocessing

- Bandpass Butterworth digital filtering to remove baseline drift and high-frequency noise [5]

- Artifact detection and rejection algorithms for motion-corrupted segments

- Pulse waveform quality assessment for inclusion criteria

Statistical Comparison

- Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for device reliability assessment

- Bland-Altman analysis with mean bias and limits of agreement

- Calculation of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy metrics for arrhythmia detection

- Statistical significance threshold typically set at p < 0.05

Research Reagents and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Equipment for PPG Validation Studies

| Device Category | Example Products | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPG Sensors | Polar OH1, Apple Watch, Garmin wearables | Optical HR and PRV monitoring | Consumer-grade PPG validation [3] [1] |

| ECG Reference Devices | Polar H10 chest strap, Holter monitors | Gold-standard electrical heart activity recording | Validation benchmark for PPG accuracy [3] [8] |

| Medical Reference Systems | Spacelabs Healthcare Holter, 12-lead ECG | Clinical-grade cardiac monitoring | Highest accuracy reference standard [8] [5] |

| Data Acquisition Tools | Polar SDK, Elite HRV app, MATLAB | Raw signal data extraction and processing | Signal-level analysis and algorithm development [3] [5] |

| Analysis Software | HRVTool MATLAB toolbox, custom JavaScript apps | HRV parameter calculation, statistical analysis | Standardized metric extraction and comparison [3] |

Factors Influencing PPG Accuracy and Reliability

Physiological and Demographic Considerations

Multiple subject-specific factors significantly impact PPG signal quality and measurement accuracy:

Body Position: PPG demonstrates excellent reliability with ECG in the supine position (ICC = 0.955-0.980 for HRV parameters) but only good to excellent reliability in seated positions (ICC = 0.834-0.921), with wider limits of agreement [3] [4]. This degradation likely results from postural influences on pulse arrival time (PAT) and pulse transit time (PTT), which affect the timing relationship between cardiac electrical activity and peripheral pulse arrival [3].

Age and Sex: Agreement between PPG and ECG is less consistent in participants over 40 years and in females, suggesting effects of age-related vascular changes and sex-specific autonomic regulation or vascular properties [3] [4]. These demographic factors should be considered in study design and result interpretation.

Skin Properties: PPG signal quality varies with skin pigmentation, with most validation studies appropriately controlling for Fitzpatrick skin phototype [3] [9]. This factor has clinical implications, as optical sensors may overestimate oxygen saturation in darker skin tones, potentially creating health disparities [9].

Measurement Context and Environment

Activity Level: PPG accuracy is highest at rest and declines during physical activity, with wrist-worn devices particularly susceptible to motion artifacts from arm movement [8] [1]. Accuracy decreases as heart rate increases, with one pediatric study showing declines from 90.9% at low HR to 79.0% at high HR for wrist-worn PPG [8].

Recording Duration: For HRV assessment, marginal differences exist between 2-minute and 5-minute recordings in resting conditions [3]. However, shorter recordings are more vulnerable to noise and motion artifacts, particularly for PPG-based sensors [3].

Environmental Factors: Ambient light interference, temperature variations, and sensor-skin contact quality all significantly impact PPG signal integrity [1]. Controlled measurement environments are essential for high-quality data collection.

Photoplethysmography represents a compelling balance between convenience and accuracy in physiological monitoring. The technology demonstrates sufficient accuracy for many applications including basic heart rate monitoring, atrial fibrillation screening, and trend-based health assessment. However, fundamental physiological differences from electrical cardiac measurement and susceptibility to various confounders necessitate careful interpretation of results.

The choice between PPG-based wearables and clinical-grade monitoring systems ultimately depends on the specific use case. For diagnostic applications and clinical decision-making, ECG-based systems remain the gold standard. For longitudinal monitoring, trend analysis, and patient engagement, PPG-based wearables offer an unparalleled combination of convenience and capability. As algorithm development continues and validation studies expand to more diverse populations, the role of PPG in both clinical and research settings will continue to evolve, potentially narrowing but unlikely to completely eliminate the performance gap with clinical gold standards.

Accuracy of Wearable Optical Sensors vs Clinical Gold Standards Research

Wearable optical sensors, particularly those using photoplethysmography (PPG), have transitioned from consumer fitness trackers to potential tools in clinical research and healthcare monitoring. These devices offer unprecedented opportunities for continuous, longitudinal health data collection outside traditional clinical settings. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the accuracy and limitations of these technologies compared to established clinical gold standards is paramount. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of wearable optical sensors across key biometric measurements, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies from validation studies.

The fundamental technological divide between consumer wearables and clinical equipment lies in their measurement approaches and regulatory oversight. Medical-grade devices typically use transmittance pulse oximetry, where light passes through tissue (e.g., fingertip or earlobe), and are FDA-regulated with strict accuracy requirements. In contrast, smartwatches and fitness trackers use reflectance PPG, where light emitted into the skin is reflected back to the sensor, and generally operate without FDA oversight for wellness tracking [10].

Comparative Accuracy of Key Biometrics

Heart Rate Monitoring

Heart rate monitoring represents the most established biometric measured by wearable technologies. Research-grade validation typically compares PPG-based wearable heart rate measurements against electrocardiogram (ECG) as the gold standard.

Table 1: Heart Rate Monitoring Accuracy Across Devices and Conditions

| Device Type | Condition | Mean Absolute Error (BPM) | Reference Standard | Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Wearables (Pooled) | At Rest | 4.6 (8.4) BPM | ECG | Sinus Rhythm | [11] |

| Consumer Wearables (Pooled) | At Rest | 7.0 (11.8) BPM | ECG | Atrial Fibrillation | [11] |

| Consumer Wearables (Pooled) | Peak Exercise | 13.8 (18.9) BPM | ECG | Sinus Rhythm | [11] |

| Consumer Wearables (Pooled) | Peak Exercise | 28.7 (23.7) BPM | ECG | Atrial Fibrillation | [11] |

| Corsano 287 Bracelet | At Rest | 94.6% accuracy within 100ms | ECG | Cardiology Patients | [12] |

| Multiple Devices | Physical Activity | 30% higher error vs. rest | ECG | All Skin Tones | [13] |

A comprehensive 2020 study systematically explored heart rate accuracy across skin tones using the Fitzpatrick scale, finding no statistically significant difference in accuracy across skin tones during various activities. However, the study revealed significant differences between devices and activity types, with absolute error during activity being 30% higher on average than during rest [13]. This has important implications for researchers designing studies involving physical activity protocols.

For patients with cardiac conditions, a validation study of the Corsano 287 bracelet demonstrated high correlation with ECG for heart rate (R = 0.991) and RR-intervals (R = 0.891), with comparable results across subgroups based on skin type, hair density, age, BMI, and gender [12].

Blood Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂)

Blood oxygen saturation represents a more challenging metric for wearable optical sensors, with significant technical and anatomical limitations affecting accuracy.

Table 2: SpO₂ Monitoring Accuracy: Wearables vs. Medical Devices

| Device | Measurement Method | Overall Accuracy | Mean Absolute Error | Gold Standard Comparison | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Pulse Oximeters | Transmittance | ~2% (FDA regulated) | ARMS ≤3% (required) | N/A | [10] |

| Apple Watch Series 7 | Reflectance PPG | 84.9% | 2.2% | Medical Oximeter | [10] |

| Garmin Venu 2s | Reflectance PPG | Not reported | 5.8% | Medical Oximeter | [10] |

| Withings ScanWatch | Reflectance PPG | 78.5% | Not reported | Medical Oximeter | [10] |

| Smartwatches (Pooled) | Reflectance PPG | 78.5%-84.9% | Variable | Arterial Blood Gas | [14] [10] |

A 2025 study comparing SpO₂ measurements in COPD patients found only a moderate correlation between smartwatch readings and arterial blood gas analysis (ICC: 0.502), which remains the clinical gold standard. The Bland-Altman analysis revealed a mean error of -1.79% between the smartwatch and blood gas measurements, with limits of agreement ranging from -7.43% to 4.87% [14].

Technical limitations significantly impact SpO₂ accuracy. Medical devices use transmittance oximetry through blood-perfused areas (finger, toe, earlobe), while smartwatches use reflectance PPG on the wrist where tendons and bones reduce blood perfusion and signal-to-noise ratio [10]. This fundamental anatomical limitation presents ongoing challenges for wrist-worn SpO₂ monitoring.

Atrial Fibrillation Detection

The episodic nature of atrial fibrillation makes continuous monitoring particularly valuable, and wearable technologies show promising but variable performance.

Table 3: Atrial Fibrillation Detection Accuracy

| Device Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Number of Studies | Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECG Smart Chest Patches | 96.1% | 97.5% | 15 | Multiple | [6] |

| PPG Smartwatches | 97.4% | 96.6% | 15 | Multiple | [6] |

| Apple Watch | 98% | Not reported | Not specified | Compared to traditional ECG | [6] |

A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies found both ECG smart chest patches and PPG-based smartwatches demonstrated excellent performance in atrial fibrillation detection. PPG smartwatches showed slightly higher sensitivity (97.4% vs. 96.1%), while ECG chest patches exhibited marginally greater specificity (97.5% vs. 96.6%) [6].

Emerging Biometrics: Hydration Monitoring

While less established than heart rate or SpO₂ monitoring, hydration tracking represents an emerging application of wearable sensor technology. A 2025 scoping review identified multiple sensor technologies being developed, including electrical, optical, thermal, microwave, and multimodal sensors. Each approach has distinct advantages and limitations [15] [16].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Laboratory Validation Protocols

Rigorous validation of wearable sensors requires carefully controlled laboratory protocols comparing wearable measurements against clinical gold standards.

Diagram 1: Laboratory validation workflow

A comprehensive validation protocol for patients with lung cancer includes both laboratory and free-living components. The laboratory protocol consists of structured activities: variable-time walking trials, sitting and standing tests, posture changes, and gait speed assessments. All activities are video-recorded for validation, with wearable sensor data compared against video-recorded observations [17].

Specific laboratory protocols typically include:

- Seated rest to measure baseline (4 minutes)

- Paced deep breathing (1 minute)

- Physical activity (walking to increase HR up to 50% of recommended maximum, 5 minutes)

- Seated rest (washout from physical activity, ~2 minutes)

- Typing task (1 minute) [13]

These controlled conditions allow researchers to assess device performance across different physical states and movement intensities.

Free-Living Validation Protocols

Free-living validation complements laboratory studies by assessing device performance in real-world conditions. A typical protocol involves participants wearing devices continuously for 7 days except during water-based activities. Outcome measures include step count, time spent at different physical activity intensity levels, posture, and posture changes. Agreement between devices is assessed using Bland-Altman plots, intraclass correlation analysis, and 95% limits of agreement [17].

Statistical Analysis Methods

Validation studies employ rigorous statistical methods to assess agreement between wearable sensors and gold standards:

- Bland-Altman plots visualize agreement between methods, plotting differences against averages

- Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) measure reliability and agreement

- Mean absolute error (MAE) quantifies average magnitude of errors

- Sensitivity and specificity calculate diagnostic accuracy for condition detection

- Mixed effects models account for repeated measures and multiple variables [14] [13] [12]

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Research-Grade Tools for Wearable Validation Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Standard References | ECG Patches (Bittium Faros 180), Arterial Blood Gas Analysis, Medical-Grade Pulse Oximeters | Provide validated reference measurements for comparison | Clinical accuracy, Regulatory approval |

| Research-Grade Wearables | Empatica E4, ActivPAL3 micro, ActiGraph LEAP | High-precision research devices | Raw data access, Extensive validation |

| Consumer Wearables | Fitbit Charge 6, Apple Watch, Garmin Devices | Test consumer device accuracy | Real-world applicability, Consumer relevance |

| Signal Processing Tools | MATLAB, Python BioSPPy, R Statistical Packages | Analyze PPG signals and derive metrics | HRV analysis, Motion artifact correction |

| Validation Software | Bland-Altman plotting tools, ICC calculation packages | Statistical analysis of agreement | Standardized validation metrics |

Factors Influencing Accuracy and Research Implications

Key Variables Affecting Measurement Precision

Multiple factors significantly impact the accuracy of wearable optical sensors:

- Motion artifacts: Physical activity can increase error by 30% or more compared to rest [13]

- Cardiac rhythm: Accuracy decreases substantially during atrial fibrillation versus sinus rhythm [11]

- Device type and placement: Research-grade devices generally outperform consumer models [13]

- Sensor technology: Reflectance PPG (wearables) has inherent limitations versus transmittance oximetry (clinical devices) [10]

- Population factors: Disease-specific characteristics (e.g., lung cancer mobility impairments) affect accuracy [17]

Implications for Research and Drug Development

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings have several important implications:

Device selection must align with research objectives - consumer wearables may suffice for general trend monitoring, while research-grade devices are preferable for clinical endpoint measurement

Study populations influence accuracy - device performance varies significantly between healthy individuals, patients with specific conditions, and those with cardiac arrhythmias

Validation is context-specific - devices should be validated for specific use cases and populations relevant to the research question

Complementary use of technologies - combining different sensor types (e.g., ECG patches with optical wearables) may provide more comprehensive monitoring

Trend analysis may be more valuable than absolute values - when absolute accuracy is limited, longitudinal trends still provide valuable insights into health status changes

Wearable optical sensors show promise for research and clinical monitoring but demonstrate variable accuracy compared to gold standard clinical methods. Heart rate monitoring is generally reliable, particularly at rest, while SpO₂ monitoring shows significant limitations. Newer applications like atrial fibrillation detection and hydration monitoring show potential but require further validation.

For researchers incorporating these technologies into studies, careful consideration of device capabilities, appropriate validation for specific use cases, and understanding of limitations are essential. As technology advances and standardization improves, wearable optical sensors are poised to play an increasingly important role in clinical research and healthcare monitoring.

In both clinical practice and biomedical research, the accuracy of physiological monitoring is paramount. "Gold standard" techniques represent the most definitive methods available for measuring a specific physiological parameter, against which all newer technologies are validated. These benchmarks, such as arterial line catheters for hemodynamic monitoring and spirometry for pulmonary function, are characterized by their well-understood operating principles, extensive validation history, and established clinical credibility. However, the rapid emergence of wearable optical sensors, particularly in clinical trials and drug development, necessitates a rigorous comparison against these reference standards. For researchers and professionals, understanding the technical basis, performance characteristics, and limitations of both traditional benchmarks and emerging technologies is essential for evaluating their appropriate application. This guide provides a structured comparison of clinical gold standards against advancing wearable alternatives, focusing on experimental methodologies for validation and the implications for data integrity in research settings.

Cardiovascular Monitoring: Arterial Lines vs. Wearable Sensors

The Invasive Hemodynamic Gold Standard

Direct arterial pressure monitoring via an indwelling arterial catheter remains the clinical gold standard for continuous blood pressure measurement, particularly in critical care and operative settings.

- Principle of Operation: A catheter is placed directly into a peripheral artery (typically radial, femoral, or brachial) and connected to a pressurized fluid-filled tubing system that transmits the arterial pressure waveform to an external electronic transducer. This transducer converts the mechanical pressure into an electrical signal, providing a real-time waveform display of systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressures.

- Key Metrics: The system provides direct, beat-to-beat measurement of arterial pressure with high fidelity and minimal latency. It allows for repeated arterial blood gas sampling and is considered the most accurate method for tracking rapid hemodynamic changes.

- Experimental Validation: Validation of arterial lines is inherent in their fundamental physical principle of direct hydraulic coupling to the bloodstream. Accuracy in clinical practice is maintained through routine calibration (zeroing) and dynamic response testing (fast-flush square-wave test) to ensure the system's natural frequency and damping coefficient are adequate for accurate waveform reproduction.

The Rise of Non-Invasive Wearable Optical Sensors

Wearable sensors for cardiovascular monitoring, primarily using Photoplethysmography (PPG), offer a non-invasive alternative. PPG is an optical technique that measures blood volume changes in the microvascular bed of tissue.

- Principle of Operation: A PPG sensor consists of a light-emitting diode (LED) that emits light (green, red, or near-infrared) into the skin and a photodetector (PD) that measures the amount of light reflected back. The pulsatile component of the captured signal (AC) is caused by arterial blood volume changes during the cardiac cycle, while the non-pulsatile component (DC) is influenced by venous blood, tissue, and bone. This AC component is used to extract physiological parameters like heart rate, pulse waveform, and through analysis, oxygen saturation and heart rate variability [18].

- Form Factors: PPG sensors are categorized as transmission-type (e.g., finger or ear clips), which provide higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), or reflection-type (e.g., wrist-worn watches/patches), which offer greater versatility for continuous, all-day monitoring despite a somewhat lower SNR [18].

- Advanced Sensor Designs: Research focuses on enhancing PPG accuracy through material and design innovations. These include developing ultra-flexible, organic photodetectors for better skin contact [18] and using multi-wavelength PPG systems combined with other sensors like ECG electrodes to create hybrid biometric capture systems. This multi-sensor fusion, as claimed by some manufacturers, addresses limitations of traditional optical sensors, such as motion artifacts and accuracy variations across different skin tones [19].

Experimental Protocol for Validation

To objectively compare the accuracy of a wearable optical sensor against the arterial line gold standard, a controlled clinical study design is required.

- Participant Cohort: Recruit a representative sample of patients already undergoing direct arterial pressure monitoring as part of their standard clinical care (e.g., in an ICU or operating room).

- Device Placement: The wearable optical sensor (e.g., a wrist-worn device or finger clip) should be applied to the patient, ensuring proper skin contact according to manufacturer guidelines. It is critical that the sensor is placed on a limb without the arterial line to avoid interference.

- Data Synchronization: Simultaneously record data from both the arterial pressure waveform and the wearable optical sensor. Precise time-synchronization of the data streams is essential for a valid beat-to-beat comparison.

- Data Analysis: For blood pressure estimation derived from PPG, comparative analysis should include:

- Bland-Altman Plots: To assess the agreement and identify any bias between the two methods across a range of pressures.

- Error Metrics: Calculation of the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressures.

- Clinical Accuracy: Evaluation based on standards such as the IEEE/Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) protocol, which requires a mean error of ≤5 mmHg and a standard deviation of ≤8 mmHg.

The workflow below illustrates the key stages of this validation protocol:

Validation Protocol Workflow

Quantitative Comparison of Performance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these two monitoring approaches, highlighting the trade-offs between accuracy and practicality.

Table 1: Comparison of Arterial Line and Wearable Optical Sensor Technologies

| Feature | Arterial Line (Gold Standard) | Wearable Optical Sensor (PPG) |

|---|---|---|

| Invasiveness | Invasive (requires arterial access) | Non-invasive |

| Measurement Principle | Direct hydraulic coupling | Optical absorption (PPG) |

| Primary Metrics | Direct systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure | Derived heart rate, pulse waveform, heart rate variability, and estimated blood pressure |

| Accuracy/Precision | High-fidelity, beat-to-beat accuracy | Varies; heart rate is generally reliable; blood pressure estimation is less accurate and requires frequent calibration [18] [19] |

| Continuity of Monitoring | Continuous, but limited to critical care settings | Continuous, enabling long-term ambulatory monitoring |

| Risk Profile | High (risk of infection, thrombosis, hemorrhage) | Very low |

| Expertise Required | High (requires trained clinician for insertion) | Low |

| Key Limitations | Cannot be used for long-term or ambulatory monitoring; high resource cost | Susceptible to motion artifacts; signal quality depends on skin perfusion and contact; accuracy can be lower in darker skin tones [18] |

Pulmonary Function: Spirometry as the Unchallenged Benchmark

Spirometry: The Definitive Test for Airflow Obstruction

Spirometry is the universally accepted gold standard for the diagnosis and monitoring of obstructive lung diseases like Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) [20]. It measures the volume and flow of air that can be inhaled and exhaled.

- Principle of Operation: A patient takes a maximal inhalation to total lung capacity, then exhales as forcefully, completely, and rapidly as possible into a spirometer. The device records the volume of air exhaled over time, generating a volume-time curve and a flow-volume loop.

- Key Metrics:

- Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1): The volume of air exhaled in the first second of a forced maneuver.

- Forced Vital Capacity (FVC): The total volume of air exhaled during the entire FEV maneuver.

- FEV1/FVC Ratio: This is the primary metric for diagnosing airflow obstruction. A post-bronchodilator ratio below 0.7 (or below the statistically derived Lower Limit of Normal, LLN) confirms the presence of obstruction, consistent with COPD [21] [20].

- Quality Control: Adherence to international standards (e.g., ATS/ERS guidelines) is critical. This includes technical requirements for spirometer calibration and biological checks, as well as procedural standards to ensure patient effort is maximal and reproducible.

Wearable Sensors for Remote Pulmonary Monitoring

While no wearable sensor currently replaces diagnostic spirometry, research is focused on developing continuous, remote monitoring solutions for respiratory rates and patterns.

- Acoustic Sensors: Small, wearable microphones or accelerometers placed on the chest or neck can capture respiratory sounds. Advanced signal processing algorithms can then derive respiratory rate and detect anomalies like wheezing or cough [22] [23].

- Chest Wall Movement Sensors: Respiratory Inductive Plethysmography (RIP) bands or strain sensors integrated into smart clothing can measure the expansion and contraction of the chest and abdomen, providing detailed information on breathing patterns, respiratory rate, and even tidal volume estimates [22].

- PPG-Derived Respiration: The PPG signal contains a respiratory component, as intrathoracic pressure changes during breathing modulate arterial blood flow. Algorithms can extract the Respiratory Rate (RR) from these modulations in the baseline (DC) and amplitude (AC) of the PPG signal [24] [18].

Experimental Protocol for Correlation

Validating a wearable respiratory sensor against spirometry involves assessing its ability to track changes in lung function or reliably measure respiratory rate.

- Participant Cohort: Include both healthy individuals and patients with varying degrees of COPD or asthma to test across a range of lung functions.

- Controlled Maneuvers: Data should be collected during a series of activities:

- Resting Breathing: To validate basic respiratory rate accuracy.

- Controlled Bronchoconstriction/Dilation: For example, using methacholine challenge or bronchodilator administration, with pre- and post-spirometry and continuous wearable sensor monitoring. This tests the sensor's ability to track dynamic lung function changes.

- Data Analysis:

- Respiratory Rate: Compare the wearable-derived RR with a visual count or capnography-derived RR using Bland-Altman analysis and correlation coefficients.

- Correlation with FEV1: Analyze if trends or specific features in the wearable sensor data (e.g., cough count, breathing pattern variability) correlate with changes in measured FEV1, even if the sensor cannot provide an absolute FEV1 value.

The logical relationship between the gold standard and the parameters measured by wearables is structured as follows:

Spirometry and Wearable Sensor Correlation Logic

Quantitative Comparison of Performance

The table below contrasts the definitive nature of spirometry with the emerging, surrogate capabilities of wearable sensors.

Table 2: Comparison of Spirometry and Wearable Respiratory Monitoring Technologies

| Feature | Spirometry (Gold Standard) | Wearable Respiratory Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Principle | Direct volumetric measurement of airflow | Indirect (e.g., chest movement, sound, PPG modulation) |

| Primary Metrics | FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, PEF | Respiratory rate, breathing pattern, cough frequency, activity level |

| Diagnostic Capability | Definitive for airflow obstruction | Cannot diagnose obstruction; monitors symptoms and trends |

| Nature of Test | Effort-dependent, performed in clinic | Passive and continuous, suitable for home monitoring |

| Accuracy & Standardization | Highly accurate and standardized (ATS/ERS) | Variable accuracy; lack of universal standards |

| Key Utility | Diagnosis, staging, and monitoring of COPD/Asthma | Longitudinal tracking of symptom burden and exacerbation risk [23] |

| Key Limitations | Point-measurement; requires patient effort and clinical visit | Provides surrogate measures; data may be influenced by motion and posture |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials for Validation Studies

For researchers designing experiments to validate wearable sensors against gold standards, the following tools and methodologies are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Validation Studies

| Item | Function in Validation | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical-Grade Data Acquisition System | Synchronized recording of gold-standard and wearable sensor data. | Systems from ADInstruments (PowerLab) or BIOPAC; must allow for precise timestamping of all data streams. |

| Signal Processing Software | Filtering, analysis, and comparison of complex physiological waveforms. | MATLAB, Python (with SciPy/Pandas), or LabVIEW for developing custom algorithms for feature extraction (e.g., pulse wave analysis, respiratory component isolation). |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | Quantifying agreement and performance metrics. | R or Python libraries for Bland-Altman analysis, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), and error (MAE, RMSE) calculations. |

| Calibrated Calibration Equipment | Ensuring the reference standard is operating correctly. | Biological calibrator ("syringe simulator") for spirometers; electronic pressure calibrator for arterial line transducers. |

| Protocols for Provocation/Challenge | Testing device performance under dynamic physiological conditions. | Methacholine for bronchoconstriction; bronchodilators (e.g., albuterol) for bronchodilation; tilt-table or exercise stress-test for cardiovascular changes. |

The comparison between clinical gold standards and wearable optical sensors reveals a landscape of complementary, rather than competing, technologies. Arterial lines and spirometry remain irreplaceable for definitive diagnosis and high-acuity management due to their direct measurement principles and proven accuracy. However, their inherent limitations— invasiveness, confinement to clinical settings, and intermittent nature—create a significant opportunity for wearable sensors.

The value of wearable optical and other sensors lies in their capacity for continuous, longitudinal, and real-world data collection. For drug development professionals, this enables the capture of rich, objective datasets on patient function and symptoms in their natural environment, potentially leading to more sensitive endpoints for clinical trials [23]. For clinical researchers, these devices offer a window into disease progression and treatment response outside the narrow snapshot of a clinic visit.

The future of physiological monitoring does not pit one technology against the other but focuses on their integration. The ongoing challenge for researchers and industry professionals is to rigorously validate wearable-derived metrics against the established benchmarks, clearly define their appropriate use cases, and continue innovating to close the accuracy gap, thereby building a new, multi-layered paradigm for patient monitoring and research.

Strengths and Inherent Limitations of Surface-Level Optical Measurements

Surface-level optical measurements are pivotal in both industrial quality control and biomedical sensing. In industrial contexts, they ensure the precision of optical components, where surface imperfections can initiate laser-induced damage [25]. In the rapidly evolving field of wearable sensors, these optical techniques have been adapted for non-invasive monitoring of physiological biomarkers, such as those found in sweat [26]. However, the accuracy of these wearable optical sensors must be rigorously evaluated against clinical gold standards to validate their utility in research and drug development. This guide objectively compares the performance of prominent optical measurement technologies, detailing their inherent limitations and strengths to inform their critical application in scientific and clinical settings.

Comparative Analysis of Optical Measurement Technologies

The selection of an appropriate optical measurement technology is a trade-off between precision, speed, robustness, and application suitability. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and limitations of five prominent optical measurement methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Optical Measurement Technologies

| Technology | Best For/Key Strength | Primary Limitations | Typical Accuracy/Precision |

|---|---|---|---|

| White Light Interferometry (WLI) [27] | Highest precision; smooth surfaces, roughness | Vibration-sensitive; complex shapes; steep edges | Nanometer-level measurements |

| Confocal Microscopy [27] | High resolution & excellent depth of field; 3D structures | Time-consuming for large areas; small working distances; vibration-sensitive | High resolution for fine details |

| Structured Light (Fringe Projection) [27] | Speed; measuring large areas quickly | Lower accuracy; high prep effort for non-matt surfaces; light-sensitive | Lower compared to WLI and Confocal |

| Laser Triangulation [27] | Speed and versatility on production lines | Shadowing issues with complex parts; struggles with reflective surfaces | Insufficient for tolerances in the hundredths range |

| Focus-Variation [27] | Versatility; complex surfaces and steep flanks | N/A (Technology is highlighted for its combination of accuracy and versatility) | High precision on complex topographies |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Validating Wearable Optical Sensors Against Gold Standards

The following methodology, adapted from studies validating wearable heart rate monitors and optical sweat sensors, provides a framework for assessing the accuracy of surface-level optical measurements in biomedical applications [8] [28].

- Objective: To validate and compare the accuracy of consumer-grade or research-grade wearable optical sensors against clinical gold-standard devices in both controlled laboratory and free-living conditions.

- Participants: A target sample size (e.g., 15-36 participants) is recruited based on the specific application, such as patients with a relevant clinical condition or healthy volunteers [28] [8].

- Devices: Participants are equipped with the optical wearable sensor(s) under investigation and the gold-standard device simultaneously.

- Procedures:

- Laboratory Protocol: Participants perform structured activities (e.g., variable-paced walking, sitting, standing) while being video-recorded for direct observation (DO) validation [28].

- Free-Living Protocol: Participants wear the devices continuously for an extended period (e.g., 24 hours to 7 days) while going about their normal daily routines [28] [8].

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Defined as the percentage of sensor readings within a certain error margin (e.g., 10%) of the gold-standard values [8].

- Agreement: Assessed using Bland-Altman plots to determine bias (mean difference) and 95% limits of agreement (LoA) [28] [8].

- Statistical Measures: Calculation of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and intraclass correlation coefficients [28].

Protocol: Correlating Surface Defects with Functional Properties

This methodology, derived from research on optical components, quantifies the relationship between physical surface characteristics and performance [29].

- Objective: To systematically investigate the quantitative correlation between surface defect dimensions and a functional property, such as laser-induced absorption.

- Sample Preparation: Artificial defects with controlled dimensions (e.g., Vickers indentations) are fabricated on a sample substrate (e.g., K9 optical glass) to simulate surface imperfections [29].

- Measurement:

- Surface Defect Characterization: The dimensions of the artificial defects are measured using a high-resolution optical technique, such as differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy [25].

- Functional Property Measurement: A corresponding functional test is performed. For example, a Surface Thermal Lensing (STL) platform is used to measure the photothermal signal and quantify absorption caused by the defects [29].

- Data Analysis: Experimental results are used to plot the functional signal (e.g., STL signal) against the defect dimension. A curve is fitted to the data to establish a quantitative correlation, verifying that increasing defect dimensions lead to heightened absorption [29].

Visualization of Technology Selection and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting an optical measurement technology and the subsequent pathway for experimental validation.

Technology Selection & Validation Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details key materials and reagents used in the development and testing of advanced optical measurement systems, particularly in the context of wearable optical sweat sensors [26].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Sensing

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible/Stretchable Polymers [26] | Substrate for wearable sensors; provides flexibility and skin adhesion. | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Thermoplastic co-polyester elastomer (TPC). |

| Hydrogels [26] | Biocompatible matrix for sweat collection; can incorporate colorimetric reagents. | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/sucrose hydrogel. |

| Colorimetric Reagents [26] | React with target biomarkers to produce a measurable color change. | Reagents for pH, glucose, chloride (Cl⁻), calcium (Ca²⁺). |

| Microfluidic Components [26] | Manage biofluid sampling; prevent contamination; enable sequential analysis. | Check valves, capillary burst valves (CBVs), suction pumps. |

| Reference Defect Standards [25] | Calibrate and quantify surface imperfection measurements. | Vickers indentations, calibrated scratch-dig standards per MIL-PRF-13830B. |

Standards for Surface Quality Specification

Quantifying surface imperfections is critical for high-precision optics. Two dominant standards govern this area:

- U.S. Standard MIL-PRF-13830B: This standard specifies surface quality using a "scratch-dig" number (e.g., 20-10). The scratch number (10, 20, 40, 60, 80) is an arbitrary indicator of scratch brightness compared to a calibrated standard, while the dig number represents the diameter of the largest pit in 1/100 mm. This method is subjective, economical, and fast, making it common for many applications. A specification of 10-5 is typically required for the most demanding laser applications [25].

- ISO 10110-7: This international standard offers a more quantitative "dimensional" method. Surface quality is expressed as

5/N x A, whereNis the number of allowed imperfections andAis the square root of the area of the maximum allowed imperfection. While more precise and objective, this method is also more time-consuming and expensive than MIL-PRF-13830B [25].

Expanding Applications in Chronic Disease Management and Remote Monitoring

The integration of wearable optical sensors into chronic disease management and remote monitoring represents a paradigm shift from episodic, facility-based care to continuous, personalized health tracking. These sensors, predominantly based on photoplethysmography (PPG) technology, utilize light to non-invasively measure physiological parameters such as heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, and potentially blood pressure [22] [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the critical question remains how these consumer-grade and research-grade devices perform against established clinical gold standards, particularly in complex patient populations. The expanding applications of these technologies are fueled by a growing market, projected to reach $7.2 billion by 2035, and their ability to facilitate decentralized clinical trials and remote patient monitoring (RPM) [22] [30]. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading wearable optical sensors, provides detailed experimental methodologies for their validation, and situates these findings within the broader thesis of assessing their accuracy against clinical benchmarks.

Performance Comparison: Wearable Optical Sensors vs. Clinical Gold Standards

Validation studies are essential to determine the contexts in which wearable optical sensors can provide clinically-reliable data. The following analysis compares the accuracy of several devices across different physiological metrics and patient populations.

Table 1: Accuracy Validation of Wearable Optical Sensors for Key Physiological Metrics

| Device / Sensor Type | Target Metric | Reference Gold Standard | Population | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitbit Charge 6 (Consumer-Grade) [17] [28] | Step Count, PA Intensity | Direct Observation, Video Analysis | Lung Cancer Patients (n=15 target) | Laboratory and free-living validation ongoing; results expected 2025. |

| Research-Grade Wrist-worn PPG (General) [24] | Heart Rate, Pulse Inconstancy | Clinical Pulse Oximetry, ECG | Healthy Adults | Enables estimation of pulse variability and oxygen saturation; accuracy high at normal gait. |

| Optical Sensors for BP (In Development) [22] | Blood Pressure | Auscultatory / Oscillometric BP | N/A | Under development; challenge in calibration and regulatory approval. |

| AI-Integrated Wearables (e.g., SepAl, i-CardiAx) [31] | Sepsis Prediction | Clinical SOFA Score, Diagnosis | Hospitalized Patients | Predicted sepsis onset 8.2-9.8 hours in advance. |

Table 2: Performance Limitations of Wearable Optical Sensors in Specific Contexts

| Limitation Factor | Impact on Accuracy / Performance | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Slow Gait Speed / Altered Mobility | Significant decrease in step count accuracy | Device accuracy decreases substantially in patients with cancer and slower walking velocities [17] [28]. |

| Skin Pigmentation | Risk of overestimating oxygen saturation (SpO₂) | PPG signals can vary with skin pigmentation, potentially missing hypoxemia in dark phototypes [31]. |

| Motion Artifacts | Signal noise and data loss | Common in free-living conditions; requires robust filtering algorithms and can lead to information overload [31]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Wearable Sensor Accuracy

A critical component of integrating wearable sensor data into clinical research is a rigorous and standardized validation protocol. The following section details methodologies from current studies to serve as a template for researchers.

Protocol for Laboratory and Free-Living Validation in Specific Populations

A 2025 validation study protocol for patients with lung cancer (LC) provides a comprehensive framework for assessing device accuracy in populations with impaired mobility [17] [28].

Objective: To validate and compare the accuracy of consumer-grade (Fitbit Charge 6) and research-grade (activPAL3 micro, ActiGraph LEAP) wearable activity monitors (WAMs) in patients with LC under laboratory and free-living conditions, and to establish standardized validation procedures [17] [28].

Study Design:

- Laboratory Protocol: Participants simultaneously wear all devices while performing structured activities, including:

- Free-Living Protocol: Participants wear the devices continuously for 7 days in their natural environment, removing them only for water-based activities. This assesses real-world performance and adherence [17] [28].

Primary Outcome Measures:

Statistical Analysis:

The workflow for this validation protocol is outlined below.

Framework for Clinical Predictive Algorithm Development

Beyond basic metric validation, advanced wearables integrate sensor data with AI for predictive monitoring. The protocol for developing and validating such systems involves a different workflow, as shown below [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers aiming to replicate validation studies or develop new sensor applications, the following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Wearable Sensor Validation Studies

| Item / Solution | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Products / Brands |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research-Grade Activity Monitors | Hardware | Provide high-fidelity, validated data on physical activity, posture, and step count; often used as a criterion measure. | ActiGraph LEAP, activPAL3 micro [17] [28] |

| Consumer-Grade Wearables | Hardware | Test the viability of low-cost, widely available devices for clinical research and remote monitoring. | Fitbit Charge 6 [17] [28] |

| Direct Observation / Video Recording System | Gold Standard | Serves as an objective, frame-by-frame reference for validating activity and posture in lab settings. | High-resolution video cameras [17] [28] |

| Validated Survey Instruments | Software | Control for confounding factors (e.g., stress, quality of life) that may influence movement patterns and device accuracy. | HRQoL, PA, and sleep surveys [17] [28] |

| FDA-Cleared Medical Devices | Gold Standard | Provide clinical-grade measurements for validating vital signs (e.g., ECG for heart rate, clinical oximeter for SpO2). | GE Healthcare's Portrait Mobile, VitalPatch [31] [32] |

| Data Analysis & Statistical Software | Software | Perform advanced statistical comparisons (Bland-Altman, ICC) and signal processing for sensor data. | R, Python, SPSS |

| AI/ML Modeling Platforms | Software | Develop and train predictive algorithms on continuous physiological data streams for early warning systems. | TensorFlow, PyTorch [31] [33] |

The expansion of wearable optical sensors into chronic disease management and remote monitoring offers unprecedented opportunities for continuous, real-world data collection in clinical research and drug development. The current evidence indicates that while these sensors show remarkable promise, particularly when integrated with AI for predictive analytics, their accuracy is not universal. Performance is contingent on the specific device, the physiological metric being measured, and the target patient population. Gait impairments, skin tone, and motion artifacts remain significant challenges to absolute accuracy.

Therefore, a cautious and validated approach is paramount. Researchers should not treat all wearable data as inherently equivalent to clinical gold standards. Instead, the future of this field lies in context-driven device selection and the implementation of standardized validation protocols, like the one detailed herein, to determine the specific boundaries of reliable use. As sensor technology and analytical algorithms continue to mature, the gap between consumer-grade wearables and clinical-grade diagnostics is expected to narrow, further solidifying their role in the next generation of clinical research and personalized medicine.

From Lab to Real World: Methodologies for Data Collection and Clinical Integration

The use of wearable optical sensors and other digital health technologies in clinical research has expanded dramatically, offering unprecedented opportunities to collect real-world mobility data outside traditional laboratory settings. However, this rapid adoption has created significant challenges for researchers and drug development professionals, primarily due to a lack of standardized protocols across studies and institutions. Heterogeneity in data acquisition protocols, sensor specifications, data formats, and analytical approaches creates substantial barriers for data sharing, reproducibility, and external validation [34] [35]. The Mobilise-D consortium, a large multi-centric study, has directly addressed these challenges by developing and implementing comprehensive procedures for standardizing the collection and processing of mobility data from wearable devices [34]. These standardized approaches are particularly crucial when validating wearable optical sensors against clinical gold standards, as they ensure that collected data is reliable, comparable, and suitable for regulatory evaluation of digital mobility outcomes (DMOs) [36]. This guide examines the protocols and insights from multi-centric studies like Mobilise-D to provide researchers with practical frameworks for standardizing data collection in their own investigations of wearable sensor accuracy.

Mobilise-D Standardization Framework: Core Components and Structure

The Mobilise-D consortium established a comprehensive framework for standardizing wearable sensor data collection across multiple clinical sites and patient populations. This framework was designed specifically to support the technical validation and clinical validation of digital mobility outcomes derived from a single wearable sensor worn on the lower back [35] [36]. The standardization procedure addresses five critical domains that are essential for ensuring data consistency and quality in multi-centric studies.

Core Standardization Domains

File Format and Data Structure: The consortium selected the .mat Matlab file format with a standardized folder structure organized by subject and recording condition (7-day, contextual, free-living, and laboratory) [35]. Each data.mat file contains wearable device and gold standard data in a consistent structure that facilitates data sharing and analysis across research groups.

Sensor Locations and Orientation Conventions: Precise specifications for sensor placement were defined, primarily focusing on a single inertial measurement unit (IMU) worn on the lower back, an ergonomically favorable position near the body's center of mass that is well-accepted by participants [37]. Standardization of sensor orientation conventions ensures consistent interpretation of sensor signals across different devices and research sites.

Measurement Units and Sampling Frequency: The protocols enforce standardized measurement units and sampling frequencies (typically 100 Hz for the primary wearable device) to enable direct comparison of data across different recording sessions and sites [35] [37].

Timing References: Implementation of synchronized timing references across all recording systems (wearable devices and gold-standard reference systems) is critical for accurate temporal alignment and validation of derived outcomes [37].

Gold Standards Integration: The framework provides detailed specifications for integrating and synchronizing data from gold-standard reference systems, such as the INDIP system (INertial modules with DIstance sensors and Pressure insoles), which combines inertial modules with distance sensors and pressure insoles for validation [37].

Multi-Cohort Study Design

The Mobilise-D approach was validated across diverse clinical populations to ensure broad applicability. The study included participants with Parkinson's Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, Proximal Femoral Fracture, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Congestive Heart Failure, and healthy older adults [38] [36]. This heterogeneous participant selection was intentional, designed to test the robustness of standardization protocols across different mobility impairments and walking characteristics.

Table 1: Mobilise-D Study Cohorts and Sample Sizes

| Cohort | Sample Size (Technical Validation) | Key Mobility Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Older Adults | 20 | Reference for normal age-related mobility |

| Parkinson's Disease | 20 | Gait impairment, bradykinesia, variability |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 20 | Fatigue-related mobility changes, ataxia |

| Proximal Femoral Fracture | 19 | Significant gait impairment, slow walking |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 17 | Exertional limitations, respiratory constraints |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 12 | Reduced exercise capacity, exertional limitations |

Quantitative Validation Results: Wearable Device Performance Across Cohorts

The Mobilise-D consortium conducted extensive validation studies to assess the accuracy of wearable-derived digital mobility outcomes against gold-standard reference systems. The validation focused on key gait parameters, including walking speed, cadence, and stride length, across different clinical populations and recording environments.

Walking Speed Estimation Accuracy

Walking speed, often termed the "6th vital sign," serves as a composite measure of walking ability and overall mobility health [38] [36]. The validation of walking speed estimation pipelines demonstrated varying accuracy across clinical cohorts and recording environments.

Table 2: Walking Speed Estimation Accuracy from Mobilise-D Validation

| Cohort | Laboratory MAE (m/s) | Laboratory MRE (%) | Real-world MAE (m/s) | Real-world MRE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Cohorts | 0.10 | 14.96 | 0.11 | 20.31 |

| Healthy Adults | 0.08 | Not reported | 0.09 | Not reported |

| COPD | 0.06 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Proximal Femoral Fracture | 0.12 | Not reported | 0.11 | Not reported |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0.12 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

The data revealed that error rates were generally higher in real-world environments compared to laboratory settings, highlighting the additional challenges posed by unscripted, daily-life activities [38]. Furthermore, cohorts with more severe gait impairments (e.g., proximal femoral fracture) typically showed higher estimation errors compared to healthier cohorts.

Gait Algorithm Performance Metrics

The consortium conducted a comprehensive comparison of multiple algorithms for estimating key digital mobility outcomes, identifying optimal approaches for different clinical populations [37].

Table 3: Performance of Best Algorithms for Key Digital Mobility Outcomes

| Digital Mobility Outcome | Best Algorithm(s) | Sensitivity | Positive Predictive Value | Absolute/Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait Sequence Detection | Cohort-specific | >0.73 | >0.75 | Not applicable |

| Initial Contact Detection | Single best algorithm | >0.79 | >0.89 | Relative error <11% |

| Cadence Estimation | Cohort-specific | >0.79 | >0.89 | Relative error <8.5% |

| Stride Length Estimation | Single best algorithm | Not applicable | Not applicable | Absolute error <0.21m |

The performance of these algorithms was influenced by walking bout duration and gait speed. Shorter walking bouts and slower gait speeds (particularly below 0.5 m/s) consistently resulted in reduced algorithm performance across all cohorts and outcomes [37]. This highlights the importance of considering these factors when designing validation protocols and interpreting results from real-world monitoring.

Experimental Protocols: Laboratory and Real-World Validation

The validation of wearable optical sensors against clinical gold standards requires meticulously designed experimental protocols that assess device performance across controlled and free-living environments. The Mobilise-D approach incorporates both laboratory-based and real-world assessment components to comprehensively evaluate device accuracy [35] [37].

Laboratory Validation Protocol

The laboratory protocol employs structured activities designed to replicate a range of mobility challenges while allowing for precise measurement using gold-standard reference systems:

Structured Walking Trials: Participants perform walking tasks at various speeds, including preferred, slow, and fast walking paces, to assess accuracy across different velocity ranges [37].

Scripted Transitions: Participants execute a series of posture changes (sitting-to-standing, standing-to-sitting) and turns to evaluate algorithm performance during non-steady-state mobility [17].

Functional Tests: Standardized clinical assessments such as the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test and walking on different surfaces (slopes, stairs) are incorporated to examine device performance during functionally relevant tasks [36] [37].

Reference System Synchronization: Laboratory sessions employ synchronized gold-standard systems such as 3D motion capture systems or the INDIP multi-sensor system (inertial modules with distance sensors and pressure insoles) to provide reference values for validation [37].

Throughout laboratory sessions, activities are typically video-recorded to enable additional verification and precise timestamp alignment between the wearable device data and reference systems [17].

Real-World Validation Protocol

The real-world validation component assesses device performance during unscripted daily activities in participants' natural environments:

Extended Monitoring Period: Participants wear the wearable device (typically on the lower back) for a designated period (e.g., 2.5 hours or 7 days) while going about their usual activities [37].

Semi-Structured Tasks: Participants are asked to perform some specific tasks during the monitoring period, such as outdoor walking, navigating slopes and stairs, and moving between rooms to ensure diversity of captured activities [37].

Reference System in Real-World: The INDIP system or similar validated multi-sensor systems are used as a reference during real-world monitoring, despite the technical challenges of deploying such systems in free-living conditions [38].

Activity Logging: Participants maintain diaries to record activities, symptoms, and notable events during the monitoring period to facilitate data interpretation and alignment [39].

This dual approach—combining controlled laboratory assessment with ecologically valid real-world monitoring—provides a comprehensive framework for establishing the accuracy of wearable optical sensors across the spectrum of mobility activities encountered in daily life.

Implementation Workflow: From Data Collection to Standardized Outputs

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for standardized data collection and processing based on the Mobilise-D approach:

Standardized Data Collection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Wearable Validation Research

Implementing robust validation protocols for wearable optical sensors requires specific technical solutions and methodological approaches. The following table details essential components derived from successful multi-centric studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Wearable Validation Studies

| Solution/Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Wearable Device | Continuous collection of inertial measurement unit (IMU) data in real-world environments | McRoberts Dynaport MM+ (single sensor on lower back) [37] |

| Multi-Sensor Reference System | Gold-standard validation for algorithm development and accuracy assessment | INDIP System (combines inertial modules, distance sensors, and pressure insoles) [37] |

| Algorithm Validation Framework | Systematic comparison of multiple algorithms for estimating digital mobility outcomes | Ranking methodology proposed by Bonci et al. [37] |

| Data Standardization Pipeline | Harmonization of data formats, sensor orientations, and measurement units across sites | Mobilise-D MATLAB-based standardization procedure [34] [35] |

| Multi-Cohort Validation Strategy | Assessment of generalizability across diverse populations with varying mobility impairments | Inclusion of neurodegenerative, respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal conditions [38] [36] |

The standardized protocols developed by multi-centric studies like Mobilise-D provide an essential framework for validating wearable optical sensors against clinical gold standards. The key insights from these initiatives demonstrate that robust validation requires comprehensive approaches encompassing both laboratory and real-world environments, diverse clinical populations to ensure generalizability, and standardized data processing pipelines to enable comparison across studies. The finding that algorithm performance varies significantly based on walking bout characteristics and clinical population underscores the importance of context-specific validation rather than one-size-fits-all approaches. Furthermore, the successful application of these standardized protocols across multiple disease cohorts supports their utility in drug development and clinical trial settings, particularly as the field moves toward regulatory acceptance of digital mobility outcomes. By adopting and building upon these standardized approaches, researchers can generate higher-quality, more comparable evidence regarding the accuracy of wearable optical sensors, ultimately accelerating their implementation in both clinical research and practice.

The evolution of wearable technology has ushered in a new era for biomedical research and clinical monitoring, creating a critical need to understand the relative performance of consumer-grade sensors against established clinical gold standards. Sensor integration—encompassing where sensors are placed, how they are attached, and how data from multiple sensors is combined—is a fundamental determinant of data accuracy and reliability. For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the transition from controlled laboratory settings to free-living environments presents unique challenges. This guide objectively compares the performance of various wearable sensor integration strategies, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies from recent validation studies, to inform their application in rigorous scientific research.

Sensor Placement, Attachment, and Their Impact on Data Quality

Strategic sensor placement and secure attachment are critical for capturing high-quality physiological signals. These factors directly influence the signal-to-noise ratio and the sensor's susceptibility to motion artifacts, which are primary sources of error in wearable data.

Common Sensor Placements and Technologies

- Wrist-Worn Placement: This is the most common form factor for consumer-grade devices (e.g., Fitbit, Garmin, Apple Watch). These devices primarily use photoplethysmography (PPG) and accelerometry. [1] While convenient, the wrist is prone to significant motion artifacts, especially during intense physical activity or fine motor tasks, which can degrade PPG signal quality. [1] [8]

- Chest-Worn Placement: Devices like the Hexoskin smart shirt incorporate sensors directly into the fabric, positioning ECG electrodes on the torso. [8] This placement provides a more stable location for cardiac electrical measurement (ECG) and is less susceptible to motion noise compared to the wrist, offering a signal closer to a clinical-grade ECG. [8]

- Neck-Worn Placement: Emerging research uses specialized neck-worn sensors like NeckSense to monitor eating behaviors by detecting jaw movements, chewing, and swallowing. This placement is chosen for its proximity to anatomical structures involved in ingestion. [40]

- Thigh-Worn Placement: Research-grade devices like the activPAL are often attached to the thigh. This placement is ideal for accurately distinguishing between sedentary postures (sitting/lying) and upright activities (standing/stepping), which is challenging for wrist-worn devices. [28]

The Influence of Attachment on Accuracy

The method of attachment is equally crucial. For optical sensors, consistent skin contact is necessary. Poor fit—either too loose or too tight—can lead to signal loss or corruption. [1] [24] As noted in a pediatric validation study, the fit of a device on a child can significantly impact measurement quality. [8] Furthermore, studies have shown that the accuracy of heart rate measurements from wrist-worn PPG sensors declines during physical activity, partly due to the motion of the device relative to the skin. [1] [8]

Table 1: Impact of Sensor Placement and Attachment on Data Quality

| Placement Location | Common Sensor Technologies | Key Advantages | Key Challenges & Impact on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist | PPG, Accelerometer | High user compliance, comfortable for long-term wear. [41] | Prone to motion artifacts; decreased HR accuracy during movement and at higher intensities. [1] [8] |

| Chest/Torso | ECG, Accelerometer, Respiration Sensors | More stable signal for cardiac and respiratory metrics; closer to clinical gold-standard placements. [8] | Less comfortable for 24/7 wear; may not be suitable for all populations. |

| Thigh | Accelerometer (high-precision) | High accuracy for classifying sedentary vs. active postures and estimating step count. [28] | Social discomfort; not ideal for capturing upper-body movement. |

| Ear | PPG, Accelerometer | Low movement artifact; useful for activity recognition. [24] | Limited surface area for multiple sensors; may not be suitable for all ear anatomies. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Wearable Sensors

Validation studies are essential for establishing the credibility of wearable sensor data. The following are detailed methodologies from key recent studies that compare wearable performance against gold-standard references.

Protocol for Lung Cancer Population Validation

A 2025 study aims to validate the Fitbit Charge 6, ActiGraph LEAP, and activPAL3 micro in patients with lung cancer, a population often experiencing gait impairments and unique mobility challenges. [28]

- Study Design: The protocol includes both laboratory and free-living components.

- Laboratory Protocol: Participants perform structured activities, including variable-paced walking trials, sitting and standing postures, and posture changes. All activities are video-recorded for direct observation (DO), which serves as the gold standard for validation. [28]

- Free-Living Protocol: Participants wear all three devices simultaneously for 7 consecutive days in their home environment, removing them only for water-based activities. [28]

- Data Analysis: Laboratory validity is assessed by comparing wearable data to video observations. Free-living agreement between devices is evaluated using Bland-Altman plots, intraclass correlation analysis, and 95% limits of agreement. [28]

Protocol for Pediatric Heart Rate Monitoring

A 2025 study investigated the accuracy of the Corsano CardioWatch (wristband) and Hexoskin (smart shirt) in a pediatric cardiology population. [8]

- Criterion Measure: A 24-hour Holter electrocardiogram (ECG) was used as the gold-standard reference. [8]

- Procedure: Participants were equipped with the Holter ECG, CardioWatch, and Hexoskin shirt simultaneously for a 24-hour free-living period. They maintained a diary of activities and sleep times. [8]

- Accuracy Definition: Heart rate accuracy was defined as the percentage of HR values within 10% of the Holter values. Agreement was further analyzed with Bland-Altman plots to calculate bias and limits of agreement. [8]

- Factor Analysis: The study analyzed how factors like BMI, age, time of wearing, and bodily movement (via accelerometry) influenced measurement accuracy. [8]

The workflow below illustrates the core components of a robust sensor validation protocol, synthesizing elements from the cited studies.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Consumer-Grade vs. Research-Grade vs. Gold Standards

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies, providing a clear comparison of device performance across different populations and metrics.

Table 2: Accuracy of Heart Rate Monitoring in Different Populations

| Device (Sensor Type) | Population | Gold Standard | Key Accuracy Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corsano CardioWatch (Wrist-PPG) | Pediatric Cardiology (n=31) | Holter ECG | Mean Accuracy: 84.8% (within 10% of Holter). Bias: -1.4 BPM (95% LoA: -18.8 to 16.0 BPM). Accuracy ↓ with higher HR and movement. [8] | Formative JMIR 2025 |