Advanced Calibration Techniques for Foot Plantar Pressure Sensors: A Guide for Biomedical Research and Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the calibration of foot plantar pressure sensors, a critical process for ensuring data accuracy in biomechanical research and clinical diagnostics.

Advanced Calibration Techniques for Foot Plantar Pressure Sensors: A Guide for Biomedical Research and Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the calibration of foot plantar pressure sensors, a critical process for ensuring data accuracy in biomechanical research and clinical diagnostics. It covers foundational principles, including the distinct calibration needs of rigid platforms versus in-shoe systems, and explores advanced methodological approaches for both normal and shear stress measurement. The content details common calibration challenges and optimization strategies, emphasizing the impact of loading conditions and anatomical specificity. Finally, it outlines rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses of different measurement technologies, offering researchers and drug development professionals a validated framework for implementing reliable and accurate plantar pressure assessment in studies ranging from gait analysis to diabetic foot ulcer prevention.

Understanding Plantar Pressure Sensing and the Critical Role of Calibration

FAQs: System Selection, Calibration, and Data Integrity

1. What are the fundamental differences between pressure platforms and in-shoe systems, and how do I choose?

Pressure platforms and in-shoe systems serve complementary roles in research. Rigid pressure platforms are typically embedded in a walkway and are considered the most accurate method for measuring plantar pressures, especially during barefoot walking or standing [1] [2]. They offer high spatial resolution and sampling frequency, making them ideal for detailed, step-by-step gait analysis in lab conditions [1] [3].

Conversely, in-shoe systems are flexible sensor arrays placed inside footwear. They are most suitable for collecting data in the field during daily living or dynamic sporting movements, as they are often wireless and can capture multiple consecutive steps [1] [4]. Their key advantage is the ability to assess the effects of footwear and orthotics on plantar pressures directly [1]. However, they usually have lower spatial resolution and sampling frequency than platform systems [1] [3].

Selection Guide:

- Use a pressure platform for high-fidelity, barefoot gait analysis in a controlled laboratory environment.

- Use an in-shoe system for studies requiring ecological validity, such as evaluating sports performance, orthotic interventions, or activities of daily living in real-world settings [1] [4] [3].

2. What calibration considerations are critical for my research validity?

Calibration is paramount for data validity. Users must consider the suitability of the manufacturer's calibration procedures for their specific application [1].

- Dynamic Calibration: Many standard testing machines used for dynamic calibration have loading rates lower than those seen in walking, let alone sporting movements. For studies involving high-impact activities, a bespoke calibration procedure that matches the expected loading rates is required to improve validity and reliability [1] [2].

- Sensor Performance: Be aware of key sensor characteristics like linearity (how linear the pressure-response curve is) and hysteresis (the difference in output between loading and unloading). Sensors with high linearity and low hysteresis simplify data processing and improve accuracy [4].

- Frequency: While some manufacturers factory-calibrate sensors and suggest they do not require frequent re-calibration, the need can vary. In applications where the sensor is re-mounted or undergoes shape changes, more frequent calibration is necessary [5].

3. How many walking trials are needed for reliable data?

Reliability improves with the number of trials. Studies suggest that for platform systems, a minimum of five trials is sufficient for many parameters to reach a value within 90% of an unbiased estimate of the mean for an individual [6]. For in-shoe systems, the required steps can be higher and depend on the walking condition. One study found that for linear walking, a distance of 207 meters was needed to achieve excellent reliability, with curved walking requiring more steps [7]. Using a two-step protocol (where the participant lands on the platform on the second step) prior to contacting the pressure plate is recommended for reliable data [1].

4. My in-shoe data seems noisy or unreliable. What could be the cause?

In-shoe systems are prone to specific artifacts that can compromise data:

- Shear Forces: These are a primary cause of sensor damage and unreliable readings. Shear forces can occur between the foot, insole, and shoe during movement [5].

- Sensor Migration: If sensors are not securely fixed, they can slip within the shoe, leading to incorrect regional pressure mapping [7].

- Environmental Factors: Sensors are often not waterproof, and sweat or moisture can affect performance. Using protective, removable sheaths is recommended [5].

- Sensor Saturation: Ensure the pressure range of your system is appropriate for the activity. High-impact movements may exceed the sensor's maximum range.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Intra-platform Reliability | Inconsistent gait velocity; insufficient number of trials; targeting the platform. | Standardize walking speed; collect a minimum of 5 trials [6]; use a two-step protocol and instruct participants not to look at the platform [1]. |

| Data Drift Over Session | Sensor hysteresis; temperature sensitivity. | Allow sensors to settle; choose sensors with low hysteresis and temperature sensitivity for the 20°C–37°C range [4]. |

| Unexpected Pressure Spikes | Sensor damage (folding, shear stress); debris on platform. | Inspect sensors for physical damage; avoid folding sensors [5]; clean the platform surface according to manufacturer guidelines. |

| Inconsistent In-shoe Readings | Sensor migration; shear forces; loose wiring. | Ensure secure fixation of the insole and sensors; check all connections for integrity [7]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials & Methods

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution Pressure Platform (e.g., emed-x) | Provides a high-fidelity benchmark for barefoot plantar pressure measurement with high spatial resolution, ideal for validating other systems or detailed gait studies [6] [8]. |

| Wireless In-shoe System (e.g., Pedar or custom smart insoles) | Enables mobile data collection during dynamic activities and sports, allowing for the assessment of footwear and orthotic interventions in real-world conditions [3] [7]. |

| Calibration Apparatus | Testing machines or custom weights for dynamic and static calibration. Critical for ensuring measurement accuracy, especially when designing bespoke protocols for high-loading activities [1]. |

| Piezoresistive Sensor Arrays | The core sensing technology in many systems. Advanced versions use materials like carbon-based inks (e.g., Carbon-Epoxy-Elastomer) screen-printed onto flexible substrates, offering high sensitivity and a wide pressure range [4] [9]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocol for Device Comparison

When comparing plantar pressure devices or conducting validation studies, follow this rigorous methodology adapted from recent research [6] [3] [7]:

- Participant Preparation: Recruit a cohort of healthy adults with no known gait abnormalities. Obtain informed consent and record demographic and anthropometric data.

- Equipment Setup: Ensure all platforms and in-shoe systems are calibrated according to manufacturer specifications immediately prior to data collection. For inter-device reliability, use multiple platforms of the same and different manufacturers.

- Data Collection: Participants should complete a minimum of 10 satisfactory walking trials per condition. Use the two-step method to collect data, where the target foot lands on the sensing area on the second step to avoid targeting behavior and ensure natural gait.

- Variables Analyzed: Extract key parameters from the processed data for the whole foot and specific anatomical regions (e.g., hallux, metatarsal heads, heel). Core metrics include:

- Peak Pressure (PP)

- Pressure-Time Integral (PTI)

- Contact Area

- Maximum Force

- Center of Pressure Excursion Index (CPEI)

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) to determine intra-device and inter-device reliability. An ICC greater than 0.70 is generally considered acceptable, with values over 0.90 indicating excellent reliability [6].

Future Directions: AI and Advanced Sensor Technology

The future of plantar pressure sensor calibration and analysis is moving toward intelligent automation. There is clear potential for AI techniques to assist in the analysis and interpretation of complex plantar pressure data, which could lead to more automated clinical diagnoses and monitoring [1] [2]. Furthermore, material science is driving innovation with novel sensors, such as high-density, screen-printed piezoresistive arrays using carbon-based nanomaterials. These sensors offer remarkable sensitivity, flexibility, and cost-effective manufacturing, paving the way for more accessible and high-resolution monitoring systems [9]. Integrating these advanced sensors with wireless communication protocols like Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) enables the development of truly mobile, wearable systems for long-term monitoring outside the lab [9] [7].

In foot plantar pressure research, calibration is not merely a recommended best practice but a fundamental prerequisite for generating valid, reliable, and clinically meaningful data. Plantar pressure measurement systems provide crucial information about the pressure field between the foot and supporting surface during locomotor activities, with applications spanning from diagnosing lower limb problems and footwear design to sport biomechanics and injury prevention [4]. The accuracy of these measurements directly impacts clinical decisions, making proper calibration non-negotiable for both research integrity and patient outcomes.

Without rigorous calibration protocols, measurement errors can propagate through data analysis pipelines, potentially leading to flawed conclusions about foot function, inappropriate therapeutic interventions, and compromised patient safety. This article establishes why calibration is indispensable through technical specifications, experimental evidence, and practical troubleshooting guidance for researchers working with plantar pressure measurement systems.

Technical Foundations: Plantar Pressure System Requirements

System Types and Configurations

Plantar pressure measurement systems generally fall into two primary categories, each with distinct calibration considerations:

Platform Systems: Constructed from flat, rigid arrays of pressure sensing elements arranged in a matrix configuration and embedded in the floor. These systems are typically used for both static and dynamic studies but are generally restricted to laboratory environments due to their stationary nature [4].

In-Shoe Systems: Feature flexible sensors embedded within footwear, measuring the interface between the foot and shoe. These portable systems enable studies across various gait tasks, footwear designs, and terrains but may have lower spatial resolution compared to platform systems and require careful sensor securing to prevent slippage [4].

Key Metrological Requirements

For any plantar pressure measurement system, several performance characteristics must be calibrated and maintained within specified tolerances [4]:

Linearity: The sensor's response should be proportional to the applied pressure throughout its measurement range. High linearity simplifies signal processing circuitry and improves measurement accuracy.

Hysteresis: This refers to the difference in sensor output when pressure is applied versus when it is released. Minimal hysteresis ensures consistent readings regardless of loading history.

Temperature Sensitivity: Sensors must maintain calibration across typical operating temperatures (20°C-37°C) encountered during human movement studies.

Pressure Range: Systems must be calibrated for the specific pressure ranges expected in target applications, from normal gait to pathological conditions.

Quantitative Evidence: Calibration Impact on Data Reliability

Consequences of Improper Calibration

Research demonstrates that calibration methodologies significantly impact measurement accuracy. A recent investigation into in-shoe plantar shear stress sensors revealed that calibration with different indenter areas (ranging from 78.5 mm² to 707 mm²) and varying positions (up to 40 mm from sensor center) produced measurement variations of up to 80% and 90%, respectively [10]. These findings highlight how seemingly minor calibration protocol deviations can profoundly affect data validity.

Reliability Metrics for Plantar Pressure Systems

Recent studies have established test-retest reliability metrics for properly calibrated wearable plantar pressure systems:

Table 1: Reliability Metrics for a Wearable Plantar Pressure System Across Different Walking Conditions

| Walking Condition | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Minimum Distance for ICC ≥0.90 | Key Parameters Measured |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Walking | ~0.9 | 207 meters | Peak Pressure (PP), Pressure-Time Integral (PTI), Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) |

| Clockwise Curved Walking | ~0.9 | 255 meters | Maximum Pressure Gradient (MaxPG), Average Pressure (AP) |

| Counterclockwise Curved Walking | ~0.9 | 467 meters | Measurements across 8 foot regions |

The system demonstrated excellent reliability for most parameters across all walking conditions when proper calibration was maintained, with all variables presenting ICCs >0.60 for whole-foot analysis [7].

Sensor Performance Specifications

Table 2: Typical Technical Specifications for Plantar Pressure Measurement Systems

| Parameter | Platform Systems | In-Shoe Systems | Impact of Poor Calibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | High (matrix configuration) | Lower (fewer sensors) | Misalignment of pressure points |

| Sampling Frequency | Up to 100 Hz | ~4 Hz to 20 Hz | Failure to capture peak pressures |

| Pressure Range | 1-112 mmHg | 10-75 mmHg | Data clipping or insufficient resolution |

| Sensor Hysteresis | Minimal | Varies by technology | Inconsistent loading/unloading data |

| Temperature Sensitivity | Compensated | Often uncompensated | Drift during prolonged use |

Calibration Protocols and Methodologies

General Calibration Workflow

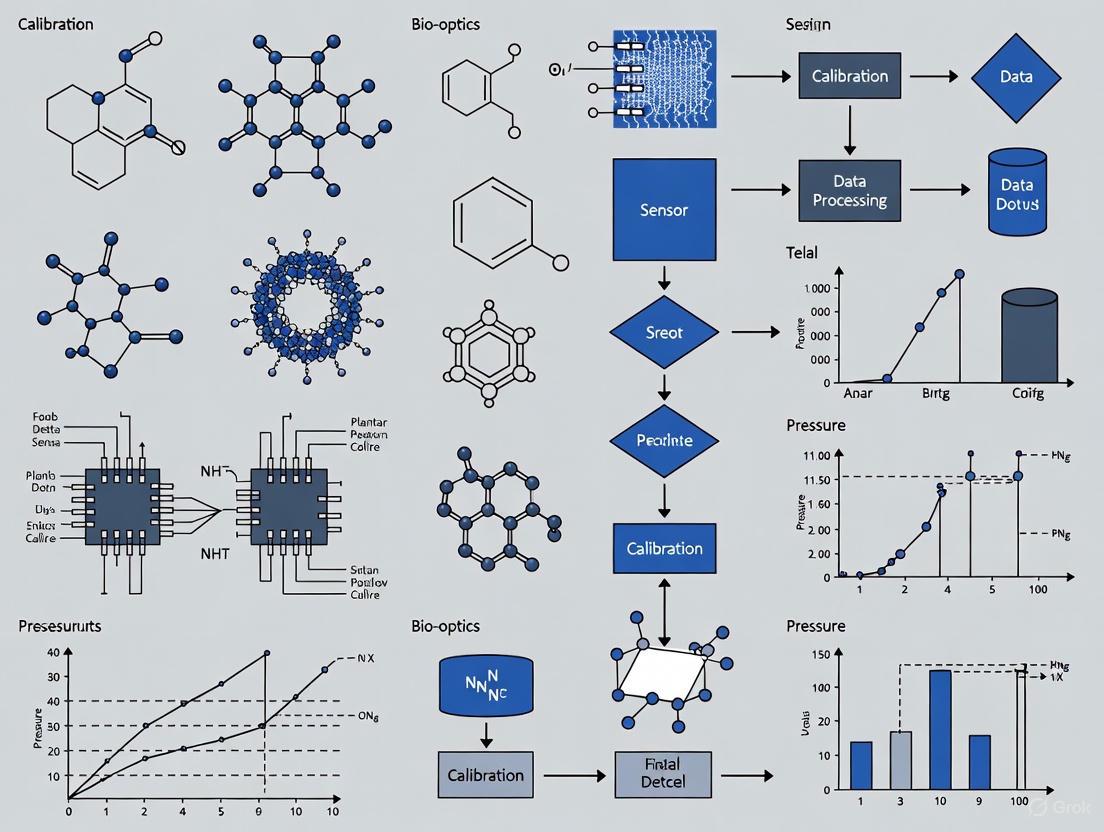

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive calibration workflow for plantar pressure measurement systems:

Anatomically-Specific Calibration Protocol

For in-shoe systems, calibration should account for anatomical variations across foot regions:

Sensor-Specific Calibration: Calibrate each sensor individually rather than applying uniform calibration factors across all sensors [10].

Region-Specific Loading: Apply calibration forces that approximate the expected loading patterns for specific anatomical regions (heel, metatarsal heads, toes).

Indenter Selection: Use calibration indenters with surface areas and geometries that match the anatomical structures applying pressure to each sensor region.

Mechanical Coupling: Account for the mechanical coupling between embedded sensors and insole materials during calibration [10].

Validation Against Gold Standard Systems

When introducing new plantar pressure devices, comparative validation against established gold standard systems is essential. One study comparing a novel plantar sensory replacement unit (PSRU) to a gold standard pressure-sensing device (Pedar-X) found:

- Good-to-very-good correlations (r-value range 0.67-0.86) for six out of eight PSRU sensors

- Poor correlation for two sensors (r=0.41, p=.15; r=0.38, p=.18) when measuring pressures greater than 32 mmHg [11]

These results highlight that even within the same system, calibration quality may vary across individual sensors, necessitating comprehensive validation protocols.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Calibration Issues and Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our plantar pressure measurements show unexpected variations between testing sessions. What could be causing this?

A: Test-retest variations can stem from multiple sources:

- Environmental factors: Temperature fluctuations can affect sensor sensitivity, particularly in piezoresistive systems. Maintain stable laboratory conditions (20°C-24°C) [4].

- Sensor drift: Some sensor technologies exhibit time-dependent drift. Implement regular recalibration schedules based on manufacturer recommendations and usage intensity.

- Donning consistency: For in-shoe systems, variations in how sensors are positioned and secured can affect measurements. Use standardized donning procedures.

- Insufficient acclimation: Participants may need 1-2 minutes to adjust to wearing the measurement system before data collection begins [7].

Q2: How often should we calibrate our plantar pressure measurement system?

A: Calibration frequency depends on:

- Manufacturer specifications: Always follow recommended intervals (typically every 6-12 months for formal metrological calibration).

- Usage intensity: Systems used heavily may require more frequent calibration.

- Criticality of measurements: For clinical applications, pre-study verification is recommended.

- Environmental conditions: Systems exposed to temperature extremes or mechanical shocks need more frequent calibration.

- Evidence of drift: Implement routine verification checks between formal calibrations.

Q3: What is the appropriate number of steps needed for reliable plantar pressure assessment?

A: The required number of steps varies by walking condition:

- Linear walking: Minimum 207 meters of walking distance [7]

- Clockwise curved walking: Minimum 255 meters [7]

- Counterclockwise curved walking: Minimum 467 meters [7] For treadmill-based assessments, other studies suggest 400 steps may be necessary for accurate measurement of step length variations [7].

Q4: How does calibration affect the ability to detect clinically significant changes in plantar pressure?

A: Proper calibration directly impacts the minimal detectable change (MDC) - the smallest change that represents a true difference rather than measurement error. Well-calibrated systems demonstrate:

- Higher intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs >0.9) [7]

- Reduced measurement variability (<21% during 15-minute walking trials) [10]

- Improved accuracy (mean absolute error <±18 kPa in benchtop tests) [10] This enhanced precision enables researchers and clinicians to detect smaller, clinically meaningful changes in plantar pressure distribution.

Q5: What are the key differences between calibrating platform systems versus in-shoe systems?

A:

Table 3: Calibration Differences Between Platform and In-Shoe Systems

| Calibration Aspect | Platform Systems | In-Shoe Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Certified pressure mats or force plates | Known weights with specific indenters |

| Environmental Controls | Laboratory conditions with stable temperature | Variable conditions during use |

| Spatial Verification | Grid-based uniformity assessment | Individual sensor verification |

| Temperature Compensation | Often built-in | May require manual compensation |

| Wear Considerations | Minimal | Regular replacement due to material degradation |

Advanced Troubleshooting Scenarios

Scenario 1: Consistent underestimation of peak pressures in specific foot regions

- Potential cause: Sensor saturation or non-linear response in high-pressure ranges

- Solution: Implement multi-point calibration covering the entire expected pressure range, with additional calibration points in high-pressure regions

- Verification: Test with known weights approximating peak pressures (often 500-800 kPa in metatarsal regions)

Scenario 2: Discrepancies between laboratory and field measurements

- Potential cause: Temperature dependence of sensor characteristics

- Solution: Characterize temperature sensitivity and implement temperature compensation algorithms

- Verification: Collect simultaneous temperature data during field measurements

Scenario 3: Progressive signal drift during prolonged data collection

- Potential cause: Material creep in sensor elements or embedding materials

- Solution: Pre-condition sensors with loading cycles before calibration

- Verification: Implement periodic zeroing during extended data collection sessions

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plantar Pressure Sensor Calibration

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Calibration Weights | Class M1 or better, various masses | Providing known forces for static calibration |

| Calibration Indenters | Various surface areas (78.5-707 mm²) and geometries | Simulating anatomical loading patterns |

| Force Plate/Reference System | Minimum accuracy 0.5% FS | Gold standard validation |

| Temperature Control Chamber | Range: 15°C-40°C, stability ±0.5°C | Temperature sensitivity characterization |

| Signal Conditioning Equipment | 24-bit ADC, appropriate sampling rates | High-fidelity signal acquisition |

| Mechanical Test Fixtures | Capable of applying combined normal/shear loads | Shear stress sensor calibration [10] |

| Reference Pressure Mats | Certified accuracy, spatial resolution <1cm² | Cross-validation of pressure distribution |

Calibration represents the fundamental link between raw sensor outputs and scientifically valid, clinically useful plantar pressure data. As demonstrated through the technical specifications, experimental evidence, and troubleshooting guidelines presented in this article, rigorous calibration protocols are non-negotiable for ensuring data validity and generating reliable clinical outcomes. The continued advancement of plantar pressure research depends on unwavering commitment to metrological rigor throughout the data collection and analysis pipeline.

By implementing the comprehensive calibration framework outlined here—including anatomical-specific protocols, regular verification schedules, and systematic troubleshooting approaches—researchers can ensure their plantar pressure measurements maintain the accuracy and reliability required for both scientific discovery and clinical application.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of piezoresistive, capacitive, and piezoelectric sensor technologies.

| Characteristic | Piezoresistive | Capacitive | Piezoelectric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Change in electrical resistance under strain [12] | Change in electrical capacitance from diaphragm movement [12] | Generation of an electric charge under applied force [12] [13] |

| Output Signal | Change in resistance (typically measured via voltage from a Wheatstone bridge) [12] | Change in capacitance or resonant frequency [12] | High-impedance electrostatic charge [13] |

| Response to Static Load | Excellent; provides stable output for constant loads [12] | Excellent; suitable for static pressure measurement [12] | Poor; inherent charge leakage prevents static load measurement [12] [13] |

| Response to Dynamic Load | Good; response time typically <1ms [12] | Good; response time in the order of milliseconds [12] | Excellent; ideal for dynamic and impact forces, with very fast response [12] [13] |

| Key Advantages | Linear output, simple construction, robust, high-pressure range capability [12] | Low power, robust, tolerant of overpressure, good for low-pressure applications [12] | Robust, self-powered, high-temperature tolerance, high-frequency response [12] |

| Key Limitations | Temperature sensitive, requires external power, scaling limitations [12] | Non-linear output (can be corrected), sensitive to stray capacitance and vibration [12] | Cannot measure static forces, sensitive to vibration/acceleration, requires special low-noise cables (charge mode) [12] [13] |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Piezoresistive Sensor Issues

Q: My piezoresistive sensor output is drifting significantly with ambient temperature changes. What could be wrong? A: Temperature drift is a known disadvantage of piezoresistive sensors [12]. First, verify that your sensor has built-in temperature compensation. If it does, ensure you are operating within the specified temperature range. For precise measurements, perform a system calibration at the expected operating temperature or implement your own temperature compensation algorithm in software based on sensor-specific data.

Q: The sensor has no output or an unstable reading. What are the initial checks? A: Follow these steps [14]:

- Visual Inspection: Check for physical damage like cracks or corrosion.

- Wiring: Ensure all connections are secure and correctly wired according to the datasheet.

- Power Supply: Verify the sensor is receiving the correct and stable supply voltage with a multimeter.

- Pressure Source: Apply a known, calibrated pressure to the sensor and compare the output to the expected value.

FAQ: Capacitive Sensor Issues

Q: The readings from my capacitive sensor are non-linear, especially at lower pressures. Is the sensor faulty? A: Not necessarily. The fundamental principle of a capacitive sensor leads to a non-linear output because the capacitance is inversely proportional to the gap between electrodes [12]. Many capacitive sensors, particularly MEMS devices, have built-in signal conditioning circuits that linearize the output. Check the sensor datasheet for its linearity specifications. For raw sensing elements, linearization must be performed in software.

Q: My capacitive system is prone to noise and erratic signals. What should I investigate? A: Capacitive sensors are highly susceptible to stray capacitance and electromagnetic interference [12]. To mitigate this:

- Keep the signal conditioning electronics as close to the sensing element as possible.

- Use shielded cables and ensure proper grounding.

- Verify that the design of your system minimizes the length of unshielded traces or wires connected to the sensor.

FAQ: Piezoelectric Sensor Issues

Q: I am trying to measure a constant force, but the output from my piezoelectric sensor decays to zero. Why? A: This is normal behavior and the primary limitation of piezoelectric sensors. They generate a charge only when the force is changing and cannot be used for true static measurements [12] [13]. The inherent electrical insulation is finite, so the generated charge will slowly leak away [13]. For long-duration, quasi-static measurements, use a sensor with a very long discharge time constant (DTC) and a charge amplifier with a long time constant setting [13].

Q: The low-frequency response of my ICP piezoelectric sensor system is poor. What factors affect this? A: The low-frequency response is governed by the system's discharge time constant (DTC). For ICP sensors, you must consider two factors [13]:

- Sensor DTC: This is a fixed value determined by the internal electronics of the sensor itself (check the datasheet).

- Coupling Circuit DTC: The AC-coupling capacitor in your signal conditioner or data acquisition system creates another high-pass filter. The system DTC is dominated by the shortest of these time constants. To improve low-frequency response, use a sensor with a long DTC and ensure your signal conditioner supports DC coupling or has a very long AC-coupling time constant.

Q: My charge-mode piezoelectric sensor system is producing noisy data. What is the likely cause? A: This is often caused by triboelectric noise [13]. Standard coaxial cable generates electrical noise when flexed. For charge-mode systems, you must always use special "low-noise" cable, which has a conductive lubricant layer to minimize this effect [13]. Also, ensure the sensor, connector, and cable are clean and dry, as moisture and dirt can provide a path for the charge to leak, causing signal drift [13].

Experimental Protocols for Plantar Pressure Research

Protocol 1: Sensor Selection & Characterization for an In-Shoe System

This protocol outlines the steps for selecting and validating sensors for foot plantar pressure measurement.

1. Define Application Requirements:

- Objective: Determine if the goal is dynamic impact analysis (e.g., running) or static/postural assessment [15].

- Sensor Type: Choose between in-shoe systems (for gait with footwear) platform systems (for barefoot analysis) [4] [15].

- Key Specifications: Based on your objective, define required pressure range, linearity, hysteresis, and sampling frequency [4].

2. Pre-Calibration Characterization:

- Linearity & Hysteresis Test: Using a calibrated materials tester or precision weights, apply known pressures from zero to maximum and back to zero. Record the sensor output at each step. Plotting the output versus input will reveal linearity and hysteresis (the difference between loading and unloading curves) [4].

- Temperature Sensitivity Test: Place the sensor in a thermal chamber and record the output under a constant load while varying the temperature across the expected range (e.g., 20°C to 37°C for biomechanical applications) [4].

3. Sensor System Integration:

- Placement: Based on foot anatomy, place sensors in key areas: heel, midfoot, metatarsal heads, and toes [4] [16]. A common model uses 15 sensors per foot [4].

- Data Acquisition: Interface sensors with a microcontroller (e.g., Arduino MEGA) and data acquisition software (e.g., LabVIEW) to convert raw voltage signals into pressure values [16].

Protocol 2: In-Situ Calibration of a Plantar Pressure Measurement System

This protocol ensures measurements are accurate after the system is built and installed in a shoe.

1. Equipment:

- Your integrated in-shoe sensor system.

- A calibrated, standalone force plate or load cell.

- A subject and a stable platform.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Have the subject stand perfectly still on the calibrated force plate, which measures the true total ground reaction force (Body Weight, BW).

- Step 2: Simultaneously, record the output from all sensors in the in-shoe system.

- Step 3: The sum of the pressures from all in-shoe sensors (converted to force) should equal the total force measured by the force plate.

- Step 4: Apply a calibration factor to each in-shoe sensor (or to the system's sum) to ensure the total measured force matches the known force from the plate. This can be done at multiple load levels (e.g., by having the subject shift weight) to create a multi-point calibration.

3. Validation:

- Have the subject perform a different activity (e.g., a slow heel raise) and check that the force data from the in-shoe system remains physiologically plausible when compared to the known dynamics of the movement.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key components for developing a foot plantar pressure measurement system, as referenced in the research.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| FSR 402 Sensors | A specific model of force-sensing resistor (piezoresistive); thin, flexible, and used in many low-cost, high-sensor-count plantar pressure platforms [16]. |

| Arduino MEGA 2560 Microcontroller | A common, programmable microcontroller board used to read analog voltage outputs from an array of sensors (e.g., FSRs) before sending data to a computer [16]. |

| LabVIEW with DAQ Hardware | Data acquisition (DAQ) software and hardware from National Instruments; widely used in research for configuring sensor input, real-time data processing, visualization, and logging [16]. |

| Low-Noise Cable | Specialized cable required for piezoelectric charge-mode sensors. Contains a conductive lubricant to minimize "triboelectric noise" generated by cable movement [13]. |

| Charge Amplifier | An electronic circuit that converts the high-impedance charge output from a piezoelectric sensor into a low-impedance voltage signal. Essential for quantitative measurement [12] [13]. |

| ICP Signal Conditioner | A constant current power source/signal conditioner for Integrated Electronics Piezoelectric (ICP) sensors. Provides the required power and decouples the AC signal from the sensor's DC bias voltage [13]. |

Sensor Operational Principles

Systematic Calibration Workflow

Key Metrics for Plantar Pressure Sensor Calibration

For researchers calibrating foot plantar pressure sensors, three metrics are paramount for ensuring data validity and reliability. Their definitions and importance in a calibration context are summarized below.

| Metric | Definition in Calibration Context | Impact on Data Quality & Research Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between a sensor's pressure reading and a true, reference value traceable to a standard [1] [17]. | Ensures clinical and biomechanical conclusions are valid. Poor accuracy can lead to misdiagnosis, incorrect athletic form assessment, and flawed research data [18]. |

| Sensitivity | The minimum change in pressure a sensor can detect, often expressed as the magnitude of output signal change per unit of applied pressure (e.g., -0.322 kPa⁻¹) [9]. | High sensitivity allows detection of subtle gait events and pressure variations, which is crucial for detailed biomechanical analysis and early-stage pathology identification [9]. |

| Spatial Resolution | The density of individual sensing elements per unit area (e.g., 4 sensors/cm²) [8]. Determines the fineness of the pressure distribution "image" [9]. | Low resolution forces interpolation of data, obscuring critical localized pressure points (e.g., under a metatarsal head). High resolution enables precise Center of Pressure (CoP) tracking [9] [1]. |

Troubleshooting Common Sensor Issues

Q1: My sensor system shows a persistent zero offset, providing a positive reading even when no pressure is applied. What could be the cause and how can I resolve it?

- Potential Causes: Residual pressure in the system, temperature fluctuations, mechanical stress on the sensor from improper mounting, or inherent manufacturing tolerances [17] [18].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Initial Check: Perform a zero balance check with the sensor at ambient conditions and confirmed zero pressure [17].

- Visual Inspection: Check for physical damage, corrosion, or loose connections [14].

- Re-mount/Re-seat: Ensure the sensor is mounted correctly per manufacturer guidelines, without misalignment or excessive torque that could cause stress [17].

- Recalibrate: If the hardware is intact, perform a zero calibration to correct the offset [18].

Q2: After a period of use, the sensor's output has become unstable or drifts over time, especially during long monitoring sessions. What should I investigate?

- Potential Causes: Temperature drift due to changes in ambient conditions or body heat, low battery power in wireless systems, electrical noise interference, or contamination of the sensor elements [14] [18].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Power Supply: Verify the sensor or data acquisition unit is receiving a stable and correct supply voltage. For wireless systems, ensure batteries are fully charged [14] [19].

- Environmental Factors: Check for sudden changes in room temperature or humidity. For in-shoe sensors, sweat can be a factor; some systems are more robust to humid conditions than others [14].

- Signal Check: Investigate potential sources of electrical interference from nearby equipment. Ensure all cabling and connectors are secure [14] [20].

- Routine Calibration: Implement a routine calibration schedule (e.g., every 6–12 months) to correct for drift due to ageing or cyclic stress [17].

Q3: My high-resolution sensor array is showing a slow or delayed response during dynamic gait activities. How can I diagnose this issue?

- Potential Causes: Problem with the sensor's internal electronics, insufficient sampling rate setting, or issues with the data transmission system (e.g., Bluetooth latency) [14] [19].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Sampling Rate: Ensure the system is configured for a sufficiently high sampling rate. For running or other high-speed motions, 100 Hz or more may be required, whereas 10 Hz might suffice for slow walking [19].

- Wiring/Connectivity: For wired systems, check connections for corrosion or damage. For wireless systems, ensure a strong, stable connection and check for data packet loss [14] [19].

- Sensor Self-Check: Some advanced insole systems feature continuous self-checks; consult the system's software for any diagnostic alerts [19].

Experimental Protocols for Calibration and Validation

Multi-Point Calibration Protocol for Accuracy and Linearity

To ensure accuracy across the entire expected pressure range, a multi-point calibration is essential. This protocol is designed to identify and correct for zero offset, span offset, and non-linearity errors [17].

Title: Multi-Point Calibration Workflow

Procedure:

- Preparation: Use a calibrated pressure source (e.g., pneumatic or mechanical tester) with a certificate of calibration traceable to international standards (e.g., ISO/IEC 17025) [17]. Ensure the sensor and environment are at a stable, controlled temperature.

- Zero Point: With no load applied, record the sensor's output. This identifies the zero offset [17] [18].

- Increasing Pressure Cycle: Apply known pressures at a minimum of 5 points (e.g., 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100% of the sensor's full-scale range) and record the output at each step. This characterizes the sensor's linearity and identifies span offset at full scale [17].

- Decreasing Pressure Cycle (Optional): For a more rigorous calibration, repeat the pressure application in descending order. The difference between readings at the same pressure during loading and unloading indicates hysteresis error [17].

- Data Processing: The calibration software uses all recorded data points to construct a transfer function (calibration curve) that converts raw sensor output into accurate pressure values.

Protocol for Validating Spatial Resolution in Gait Analysis

This protocol validates whether a system's spatial resolution is sufficient for capturing critical gait features.

Procedure:

- Setup: Use a high-resolution pressure sensing walkway (as a reference) with a density of 4 sensors/cm² or higher [8]. Simultaneously, fit the subject with the in-shoe sensor system to be validated.

- Data Collection: Have the subject walk at a self-selected pace across the walkway while wearing the instrumented insoles. The walkway captures barefoot steps, while the insoles capture in-shoe pressure.

- Analysis: For the in-shoe system, assess its ability to resolve key anatomical landmarks from the pressure map, such as the hallux, 1st and 5th metatarsal heads, and the heel. Compare the sharpness of these features and the smoothness of the Center of Pressure (CoP) trajectory to the high-resolution walkway data. A system with insufficient resolution will show blurred landmarks and a CoP path with fewer, more abrupt data points [9] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and equipment essential for the calibration and experimental use of plantar pressure sensors.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specifications & Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Calibrated Pressure Source / Tester | Applies known, precise pressures to sensors for calibration. Serves as the reference standard. | Types: Pneumatic (for low pressures), hydraulic (for high pressures), mechanical deadweight testers (gold standard). Must have a valid calibration certificate traceable to NIST or similar bodies [17]. |

| High-Resolution Pressure Sensing Walkway | Provides a reference for validating the spatial accuracy of in-shoe systems during dynamic tasks like gait. | Example: 1.2m x 3.6m runway with 240 x 720 sensors (4 sensors/cm²) [8]. Used for barefoot pressure analysis and as a benchmark. |

| Screen-Printed Piezoresistive Sensor Array | The core sensing element in many advanced research insoles. Converts mechanical pressure into a measurable change in electrical resistance [9]. | Example: 173 sensors on a flexible printed circuit board (fPCB) using a Carbon-Epoxy-Elastomer (CE2) ink. Offers high sensitivity (-0.322 kPa⁻¹) and flexibility [9]. |

| Wireless Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | Enables untethered, real-world data collection from sensor insoles, critical for capturing natural gait. | Features: Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) for real-time transmission, onboard memory for standalone recording, IMU integration for motion context, and synchronization capabilities with other MOCAP systems [19]. |

| Trimmable In-Shoe Sensor | Allows for a custom fit within different shoe sizes and types, ensuring the sensor placement is consistent and comfortable for the subject. | Example: Sensors can be trimmed to fit up to a men's size 14 shoe. Cutting must avoid damaging the conductive silver traces and sensing elements [21]. |

The pursuit of peak athletic performance and injury prevention increasingly relies on data from sophisticated measurement systems like plantar pressure sensors and motion capture technologies. However, a significant "calibration gap" exists between standardized laboratory calibration procedures and the dynamic, high-intensity movements characteristic of sports. This gap can compromise data reliability, leading to flawed conclusions and suboptimal interventions. This technical support center addresses why bespoke, sport-specific calibration protocols are essential and provides researchers with the tools to implement them.

Core Problem: Traditional calibration methods often fail under sporting conditions due to factors like:

- High Loading Rates: Sporting movements (e.g., sprinting, jumping) exert forces far exceeding those in standard walking calibrations [1] [2].

- Environmental Variability: Conditions in aquatic, outdoor field, and indoor court environments differ vastly from controlled labs [22].

- Dynamic & Unpredictable Movements: Athletic motions involve complex, multi-directional forces that generic protocols do not capture [22].

Understanding the Technology and Its Limits

Plantar pressure measurement is a key tool for assessing foot function and locomotion in sports and health [1] [2]. Researchers typically use two main types of systems:

| System Type | Best For | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Pressure Platforms [1] [2] | Barefoot assessment in lab settings; standing, walking. | High accuracy; high spatial resolution and sampling frequency. | Limited to lab environment; not for use with footwear. |

| In-shoe Pressure Systems [1] [2] | Field-based measurements during dynamic sports; assessing footwear/orthotics. | Wireless, portable; allows multiple steps in realistic conditions. | Lower spatial resolution and sampling frequency than platforms. |

Quantifying system performance under realistic conditions is crucial. The table below summarizes accuracy metrics for related motion capture technologies, illustrating the performance variations across different environments [22]:

| Technology | Typical Accuracy | Key Environmental Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Marker-Based Systems | Sub-millimeter positional accuracy [22] | Controlled lab environments; reflections and marker occlusion in the field [22]. |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) Systems | 2–8° angular accuracy [22] | Performance varies with movement complexity [22]. |

| Markerless Computer Vision Systems | Sagittal plane: 3–15°; Transverse plane: 3–57° [22] | Variable accuracy, especially in transverse plane [22]. |

| GNSS-Integrated Tracking | ±0.3–3 m positional accuracy [22] | Performance challenges in outdoor fields [22]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Inconsistent Data During High-Impact Activities

Problem: Plantar pressure data becomes noisy or unreliable during movements like sprinting or landing from a jump.

Solution: Implement a dynamic calibration protocol that matches the loading rates of your sport.

- Verify Manufacturer's Calibration Specifications: Check the dynamic loading rates used by the manufacturer for calibration. Many testing machines use loading rates "less than even those found in walking" [2].

- Develop a Bespoke Calibration: If the factory calibration is insufficient, create a custom procedure. This involves:

- Cross-Validate with a Supplementary System: In the lab, use a force plate or a high-speed motion capture system (e.g., optical marker-based) simultaneously with your in-shoe sensors during sport-specific tasks. This provides a "gold-standard" reference to check the accuracy of your pressure data [22] [24].

Guide 2: Managing Data Artifacts from Environmental Factors

Problem: Data is affected by factors like temperature, moisture (sweat/water), or uneven flooring.

Solution: Proactively control and document environmental variables.

- For Aquatic Sports or High-Sweat Conditions:

- Use sensors with waterproofing or moisture-wicking interfaces.

- Conduct pre- and post-session calibration checks in the same environment to quantify drift. IMU systems, for example, can show an additional 2° orientation error in aquatic settings [22].

- For Outdoor Field Testing:

- Be aware that systems like GNSS can have positional accuracy from ±0.3m to 3m [22].

- Note the ground surface (e.g., artificial turf vs. natural grass) and weather conditions in your metadata, as these can affect both the sensor and the movement itself.

Guide 3: Ensuring Results are Reproducible Across Multiple Sites

Problem: A study involving multiple labs or testing locations yields inconsistent results.

Solution: Standardize protocols and equipment across all sites, focusing on reproducibility.

- Create a Detailed Standard Operating Procedure (SOP): Document every step, including:

- Sensor Preparation: Exact sensor placement and securing method within the shoe.

- Subject Preparation: Standardized footwear and warm-up routine.

- Data Collection Protocol: The exact sequence of movements (e.g., "three consecutive jumps at maximal effort").

- Conduct Inter-Site Reliability Testing: Have a small group of athletes perform the same protocol at each testing site. Analyze the data to ensure consistency (low inter-site variability) before beginning the full study [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I just use the manufacturer's standard calibration for my sports study? Standard calibrations are often designed for clinical applications like walking or standing. Sporting movements involve much higher forces, faster loading rates, and different foot strike patterns. Using a generic calibration can lead to significant under-reporting of peak pressures and inaccurate data [1] [2].

Q2: How often should I re-calibrate my pressure measurement system? The frequency depends on usage intensity. For daily research use with high-impact activities, a weekly verification check is recommended. Perform a full calibration before starting a new study or if you suspect the system has been subjected to a physical shock. Always follow manufacturer guidelines as a minimum standard.

Q3: What is the difference between repeatability and reproducibility, and why does it matter?

- Repeatability is about getting consistent results when the same user measures the same subject multiple times under identical conditions.

- Reproducibility is about getting consistent results across different users, different locations, or over time. In sports science, both are critical. High repeatability ensures your internal data is reliable. High reproducibility allows other researchers to trust and build upon your findings [24].

Q4: How can AI help with the analysis of plantar pressure data? AI and machine learning techniques have clear potential to assist in analyzing complex pressure data. They can help identify subtle patterns related to injury risk or performance optimization that might be missed by traditional analysis, enabling more complete use of the rich dataset these systems generate [1] [2].

Experimental Protocols for Bespoke Calibration

Protocol 1: Sport-Specific Dynamic Calibration

Objective: To calibrate an in-shoe plantar pressure system for forces and loading rates typical of basketball vertical jumps.

Materials:

- In-shoe pressure measurement system.

- High-capacity materials testing machine (e.g., Instron).

- A calibrated force plate (for cross-validation).

Workflow:

- Setup: Place the sensor or insole in the testing machine, ensuring even contact.

- Parameter Setting: Program the machine to apply a loading profile that mimics the impact force and rate observed in a basketball jump. This profile should be based on pilot data from force plates.

- Data Collection: Run multiple cycles (e.g., 20-30) to ensure sensor reliability.

- Validation: Have an athlete perform vertical jumps on a force plate while wearing the calibrated in-shoe system. Compare the peak force and loading rate from both systems to validate the calibration.

The following workflow outlines the key stages of this protocol:

Protocol 2: Multi-Site Reproducibility Assessment

Objective: To ensure a plantar pressure protocol for running gait analysis yields consistent results across three different research laboratories.

Materials:

- Identical in-shoe pressure systems at each site.

- Standardized running shoes.

- A treadmill.

Workflow:

- SOP Development: Create a detailed protocol document covering sensor placement, shoe model, treadmill speed/incline, and data output requirements.

- Centralized Training: Train all technicians from the three sites on the SOP.

- Test with Traveling Subjects: A small cohort of runners visits all three sites and performs the running protocol.

- Data Analysis: Compare key metrics (e.g., center of pressure trajectory, peak heel pressure) across sites using statistical tests for agreement (e.g., ICC). Revise the SOP if reproducibility is low.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Rigid Pressure Platform | Provides high-accuracy "ground truth" data for barefoot static or low-dynamic assessments in a lab setting [1] [2]. |

| In-shoe Pressure System | Enables the measurement of plantar pressures in ecological settings during dynamic sporting movements and with footwear [1] [2]. |

| Materials Testing Machine | Used for developing bespoke dynamic calibration protocols by applying controlled, sport-specific loading rates and forces to sensors [1] [2]. |

| Gravimetric Calibration Setup | The primary method for flow measurement traceability; uses precision balances to measure mass over time, providing a foundational reference [23]. |

| High-Speed Cameras | Used for motion capture (e.g., markerless systems) and optical calibration methods (e.g., front track, pending drop) to track movement with high temporal resolution [22] [23]. |

| Force Plates | Integrated with motion capture and pressure data to provide synchronized kinetic (force) information, crucial for validating sensor output during high-impact tasks [22]. |

Key Takeaways for Researchers

- Move Beyond Standard Calibration: For sport science, bespoke protocols matching the movement's intensity and complexity are non-negotiable for data accuracy [1] [2].

- Quantify the Gap: Use frameworks like the STRN Quality Framework to systematically evaluate your technology's accuracy, repeatability, and reproducibility in a sporting context [24].

- Embrace a Multi-Method Approach: No single system is perfect. Combine technologies (e.g., in-shoe sensors with force plates or IMUs) to cross-validate data and gain a more complete biomechanical picture [22].

- Prioritize Reproducibility: Detailed SOPs and inter-site reliability testing are essential for producing credible, collaborative research that can be replicated by others [24].

Implementing Calibration Protocols: From Bench Top to Real-World Application

Standard Dynamic Calibration Procedures and Testing Machines

In foot plantar pressure research, dynamic calibration is a critical process that ensures measurement systems accurately capture the rapid, high-magnitude loads encountered during human locomotion. Unlike static calibration, dynamic calibration validates sensor performance under conditions that simulate real-world gait and athletic movements, accounting for factors like loading rate and impact force. This technical support center document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with comprehensive guidance on calibration protocols, testing equipment, and troubleshooting for plantar pressure measurement systems. Proper calibration is foundational to obtaining valid and reliable data for applications ranging from footwear design and sports performance to clinical diagnosis and rehabilitation [2] [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Calibration and Testing

Q1: Why is dynamic calibration specifically necessary for plantar pressure sensors, beyond static calibration? Dynamic calibration is essential because it accounts for the loading rates experienced during actual human movement. Static calibration alone is insufficient for characterizing sensor performance during gait or impact. Research indicates that many testing machines used for dynamic calibration have loading rates lower than those found even in walking, let alone running or jumping [2]. Dynamic calibration ensures the validity and reliability of data collected during dynamic sporting movements and daily activities by verifying sensor response time, hysteresis, and accuracy under realistic loading conditions.

Q2: What are the key performance metrics for a plantar pressure measurement system? When selecting and calibrating a system, researchers should evaluate several critical technical specifications [25] [4] [26]:

- Linearity: Indicates how directly the sensor's output corresponds to the applied pressure. A highly linear sensor simplifies signal processing.

- Hysteresis: The difference in output signal when the sensor is loaded versus unloaded. Lower hysteresis (e.g., <7% as specified for the pedar system) means less energy loss and better accuracy during the cyclic loading of gait [26] [27].

- Sampling Frequency: The rate at which pressure data is captured. For dynamic activities, higher frequencies (e.g., 150 Hz [25] to 400 Hz [26] [27]) are necessary to accurately capture rapid pressure changes.

- Pressure Range: The span of pressures the system can measure. It must be suited to the application, from low pressures in balanced standing to very high pressures in athletic jumps (e.g., ranges up to 1200 kPa are available) [26] [27].

- Spatial Resolution: The number of sensors (sensels) per unit area. Higher resolution provides more detailed pressure maps, which is crucial for identifying localized high-pressure points [25] [4].

Q3: What is the recommended protocol for clinical gait analysis using pressure insoles? For reliable data collection in gait analysis, a standardized protocol is vital. The literature recommends a "two-step" protocol prior to the foot contacting the measurement area [2]. This approach helps ensure that the subject's gait has reached a natural and consistent state before data is recorded, minimizing artifacts from initiation or adjustment steps.

Q4: How often should a plantar pressure measurement system be calibrated? Best practices recommend that systems are factory calibrated before use, and their calibration should be checked by the user regularly using a dedicated calibration device [26] [27]. For example, the pedar system is designed to be used with the trublu calibration device, which allows users to verify and ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of their data at any time [26] [27]. The specific calibration interval may depend on usage intensity and the manufacturer's guidelines.

Dynamic Calibration Procedures & Testing Machines

Standard Calibration Methodologies

Dynamic calibration for plantar pressure sensors involves applying known, rapidly varying pressures to the sensor and correlating the system's output with the reference input. A key challenge in this field is that many existing testing machines operate at loading rates lower than those generated by common human movements, which can lead to an overestimation of system accuracy in real-world scenarios [2]. Therefore, developing calibration protocols that match the loading rates of the target activities (e.g., running, cutting, jumping) is an active area of research and is critical for high-quality studies.

Commercial systems often use dedicated calibration devices. For instance, the pedar system is individually calibrated with the trublu calibration device, which applies a known air pressure to all sensors simultaneously, ensuring each sensor provides accurate and reproducible data [26] [27]. These systems are designed with calibration stability in mind, allowing for the collection of thousands of gait cycles with minimal set-up time and drift [25].

The following table summarizes the technical specifications of several plantar pressure measurement systems as identified in the literature, highlighting the performance parameters relevant to calibration and experimental use.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Commercial Plantar Pressure Measurement Systems

| System / Feature | Intelligent Insoles | Pro (XSENSOR) | pedar System (novel) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Gait & motion research, sports performance [25] | In-shoe pressure distribution, versatile applications [26] [27] |

| Calibration Approach | Factory calibrated with proven stability [25] | Individual insole calibration via trublu device [26] [27] |

| Sampling Frequency | Up to 150 Hz [25] | Up to 400 Hz [26] [27] |

| Sensor Resolution (per insole) | Up to 235 sensels [25] | 99 or 175 sensels [26] [27] |

| Hysteresis | Not explicitly stated | < 7% [26] [27] |

| Pressure Range | 0.7-88.3 n/cm² (1-128 psi) [25] | 15-600 kPa or 30-1200 kPa [26] [27] |

| Key Features | Lab-quality data in the field; integrated IMU [25] | High-conformity capacitive sensors; WiFi telemetry; on-board storage [26] [27] |

Workflow for Sensor Setup and Validation

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for setting up and validating a plantar pressure measurement system prior to an experiment, incorporating best practices from the literature.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Systematic Problem Diagnosis Framework

When experimental data appears erroneous, a structured approach to diagnosis is crucial. The following workflow guides researchers through a logical series of checks to identify the root cause of common pressure measurement problems, from simple connection errors to complex environmental factors.

Troubleshooting Guide: Symptoms, Causes, and Solutions

The table below details specific symptoms, their potential root causes, and recommended corrective actions based on general pressure sensor troubleshooting principles and application-specific challenges in biomechanics research.

Table 2: Plantar Pressure Sensor Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Output or Unstable Output | - Loose or incorrect wiring [14] [28].- Inadequate or no power supply [14].- Internal sensor failure. | - Verify all electrical connections and wiring according to datasheet [14].- Confirm the sensor is receiving the correct supply voltage with a multimeter [14].- Contact technical support if hardware is suspected to be faulty [14]. |

| Inaccurate Reading / Drift | - Calibration drift over time [28].- Temperature drift due to lack of compensation [14].- Exposure to extreme temperatures or thermal cycling [29]. | - Perform a new calibration using a certified calibration device [26].- Check sensor specifications for temperature compensation range [4].- Allow system to acclimate to lab temperature and protect from rapid temperature changes [29]. |

| Slow or Delayed Response | - Problem with internal electronics or signal conditioning [14].- Clogged pressure port (if applicable) from contamination [14].- Use of an electrical output type (e.g., millivolt) prone to interference over long distances [28]. | - Inspect and clean sensors, ensure no obstructions [14].- For wireless systems, ensure high sampling frequency is selected and check for data transmission lag.- Use voltage or current output systems for better noise immunity in industrial/field environments [28]. |

| Erratic Data During Movement | - Sensor insole slipping or folding inside the shoe.- Low battery power in wireless units.- Electromagnetic interference (EMI) from other lab equipment [29]. | - Secure the insole properly to prevent movement relative to the foot.- Ensure full battery charge before experiments.- Use systems with digital outputs and proper shielding; increase distance from EMI sources [29]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers designing experiments in foot plantar pressure, having the right "toolkit" is essential for generating valid and reproducible data. The following table lists key equipment and materials as identified in the scientific literature and commercial product documentation.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Plantar Pressure Experiments

| Item | Function / Purpose | Representative Examples / Specs |

|---|---|---|

| Calibrated Pressure Insoles | The primary sensor for measuring pressure distribution at the foot-shoe interface. | XSENSOR Intelligent Insoles | Pro [25]; novel pedar insoles [26] [27]. |

| Dedicated Calibration Device | Applies a known, uniform pressure to validate and/or calibrate all sensors on the insole, ensuring accuracy. | novel trublu calibration device [26] [27]. |

| Wireless Data Acquisition Unit | Transmits sensor data without restricting natural movement, crucial for field-based and dynamic activities. | plidar electronics (54g, WiFi, 400 Hz) [26] [27]; XSENSOR systems with on-board memory [25]. |

| Analysis Software | Visualizes, processes, and quantifies pressure data (e.g., peak pressure, force, center of pressure trajectory). | XSENSOR Pro Foot & Gait software [25]; novel Scientific Studio & E-Expert packages [26]. |

| Standardized Testing Platforms | Creates controlled and repeatable conditions for dynamic tasks like stair descent. | Custom steps of varying heights (e.g., 5cm, 15cm, 25cm, 35cm) [30]. |

| Reference Measurement Systems | Provides synchronized biomechanical data for more comprehensive analysis (multi-modal data). | Motion capture systems, force platforms, electromyography (EMG) [26]. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my shear stress sensor measurement inaccurate even after a standard calibration?

A: A primary cause is the use of a generic calibration protocol that does not match the anatomical loading conditions of the foot. Research demonstrates that calibration accuracy is highly sensitive to the indenter area and location used during bench testing. Using an indenter that does not match the size and position of specific foot anatomical structures (like the metatarsal heads) can introduce errors of up to 80-90% [31]. Furthermore, shear and normal stress are coupled; the sensor's response to shear force is influenced by the simultaneous normal load, a factor that must be accounted for in the calibration model [31].

Q2: My data shows poor agreement with other studies. Could the issue be with the measurement system itself?

A: Yes, significant discrepancies exist even between different commercial systems. A systematic comparison of plantar pressure devices revealed poor to moderate agreement, even among devices using similar sensor technologies [32]. The data from different devices should not be used interchangeably [32]. Ensure you are comparing results from the same sensor technology and calibration methodology, and report these details thoroughly in your methods.

Q3: Why do my sensor readings drift during a walking trial?

A: Drift is a common challenge, often linked to the sensor technology and environmental factors. Materials like the elastomers used to embed sensors can exhibit properties like creep and hysteresis [33] [31]. Additionally, temperature and humidity variations inside the shoe can affect sensor output [33]. To mitigate this, precondition the sensors by loading them for a period before calibration and use a calibration method that accounts for time-dependent behavior [33].

Q4: What is the most critical factor for achieving accurate in-shoe shear stress measurements?

A: The consensus across recent research is the mechanical coupling between the embedded shear sensors and the insole materials, and the use of an anatomically-specific calibration method [31]. A generic, one-size-fits-all calibration is insufficient. The calibration must replicate the specific loading profile, area, and location of the anatomical region of interest.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability (>20%) in repeated walking trials | Poor mechanical coupling; sensor shifting inside shoe; inconsistent calibration. | Secure sensor firmly within the insole material. Use an indenter matching the anatomical area for calibration [31]. |

| Shear stress values are consistently unrealistic (too high/too low) | Incorrect calibration factors; normal-shear stress coupling not accounted for. | Re-calibrate using a protocol that decouples normal and shear stress effects. Use the mathematical model: σS = E * kS * (SN+S - SN) / (1 + ε) [31]. |

| Measurements disagree with force platform gold standard | Systemic device error; different sensor technologies; improper calibration method. | Do not expect perfect agreement. Validate your system against a force platform and report the expected error margins [32] [33]. Use a participant weight-based calibration to improve impulse accuracy [33]. |

| Sensor signal is noisy or unstable | Loose electrical connections; environmental interference (temperature, humidity). | Check all wiring and connections. Use shielded cables. Allow the system to acclimate to the testing environment before calibration and data collection [33]. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Calibration Data

The following data, derived from controlled bench tests, highlights the critical parameters for anatomical calibration.

Table 1: Impact of Calibration Indenter Parameters on Measurement Accuracy [31]

| Calibration Parameter | Variation Tested | Effect on Measurement Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Indenter Area | 78.5 mm² to 707 mm² | Measurements varied by up to 80% |

| Indenter Position | Up to 40 mm from sensor center | Measurements varied by up to 90% |

| Calibration Method | Anatomically-specific vs. Generic | Anatomical calibration reduced mean absolute error to < ±18 kPa |

Table 2: Comparison of Insole System Calibration Methods [33]

| Calibration Method | Description | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer's Standard | Proprietary protocol provided by the insole manufacturer. | Pro: Standardized. Con: May lead to significant inaccuracies in impulse values (≈30-50% error). |

| Participant Weight-Based | Uses the participant's body weight to adjust the static calibration. | Pro: Can improve qualitative representation. Con: Can consistently underestimate impulse values. |

| Anatomically-Specific | Uses indenters matching the size/location of foot anatomy. | Pro: Highest accuracy, accounts for real-world loading. Con: More complex and time-consuming. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Anatomically-Specific Sensor Calibration

This protocol is designed to minimize the errors identified in the FAQs and tables above.

Objective: To calibrate a plantar shear stress sensor using indenter parameters that match the anatomical region of interest (e.g., first metatarsal head).

Materials:

- Shear stress sensor embedded in silicone insole

- Custom mechanical test rig capable of applying controlled normal and shear forces

- Indenters with various surface areas (e.g., 78.5 mm², 707 mm²)

- Data acquisition system

- Force platform (for optional validation)

Procedure:

- Preconditioning: Cycle the sensor by applying a load equivalent to the expected maximum force for 10-15 cycles to minimize the effects of hysteresis and creep [33].

- Indenter Selection: Select an indenter whose contact area closely matches the surface area of the anatomical structure being studied (e.g., a metatarsal head).

- Normal Stress Calibration:

- Apply normal force to the sensor using the selected indenter in increments from 0% to 100% of the expected load.

- Record the output from the normal stress sensor (NN) at each increment.

- Generate a normal force-to-output voltage calibration curve.

- Shear Stress Calibration:

- Apply a constant normal load (e.g., 50% of maximum).

- Apply shear force in the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral directions in increasing increments.

- Record the output from the shear strain gauge (SN+S) at each increment.

- Repeat for different levels of constant normal load to capture the coupled relationship.

- Positional Sensitivity Mapping:

- Place the indenter at the center of the sensor and perform a normal and shear calibration.

- Offset the indenter by 5mm, 10mm, 20mm, and 40mm and repeat the calibration process to map the positional sensitivity [31].

- Data Processing:

- Use the recorded data to solve for the calibration constants (kN, kS) in the following equation, which decouples the normal and shear effects [31]:

σS = E * kS * (SN+S - SN) / (1 + ε)whereEis the silicone's Young's Modulus andεis the strain.

- Use the recorded data to solve for the calibration constants (kN, kS) in the following equation, which decouples the normal and shear effects [31]:

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Plantar Sensor Research

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Strain Gauge Rosette | The core sensing element for measuring shear stress. A 3-element rosette (0°-45°-90°) allows for calculation of resultant shear in both anterior-posterior and medial-lateral directions [31]. |

| Hyperelastic Silicone Elastomer | An incompressible, isotropic embedding material that couples plantar loads to the shear sensor. Its non-linear stress-strain relationship must be characterized for accurate calibration [31]. |

| Custom Mechanical Test Rig | A calibrated system to apply precise and combined normal and shear forces to the sensor-insole assembly during the benchtop calibration process [31]. |

| Anatomically-Matched Indenters | Indenters with varying surface areas and shapes (e.g., circular, elliptical) used to simulate the loading from specific foot anatomical structures during calibration [31]. |

| Calibration Management Software | Software used to document calibration procedures, track intervals, analyze historical drift data, and manage calibration certificates for traceability [34]. |

Troubleshooting Common Sensor and Calibration Issues

Q1: Our screen-printed piezoresistive sensors exhibit significant signal drift over time. What could be causing this and how can we mitigate it?

A: Signal drift in piezoresistive sensors can stem from material instability, poor contact, or environmental factors. To mitigate:

- Material Properties: Ensure the carbon-based nanomaterial ink is thoroughly homogenized before printing to prevent filler sedimentation, which causes inconsistent percolation networks [35] [36].

- Stabilization Cycle: "Condition" new sensors by applying a series of loading and unloading cycles (e.g., 100-1000 cycles at expected operating pressures) to stabilize the conductive network's response before formal data collection [35].

- Environmental Control: Monitor laboratory temperature and humidity, as these can affect the electrical properties of polymeric and carbon-based materials. Conduct calibrations in a controlled environment [32].

Q2: When comparing data from our in-shoe system to a pressure platform, we observe poor agreement in key metrics like peak pressure. Why is this happening?

A: Discrepancies between systems are common and well-documented [32]. Key reasons include:

- Fundamental Design Differences: In-shoe systems and pressure platforms use different sensor technologies, densities, and are used in different conditions (shod vs. barefoot) [1] [32].

- Calibration Protocol Mismatch: The two systems may be calibrated using different protocols and loading rates. Develop a unified, application-specific calibration that mimics the dynamics of your movements, such as sporting actions, if applicable [1].

- Shear Stress: In-shoe systems can experience shear forces that platform systems do not, which may affect sensor output [7]. Ensure sensors are securely fixed within the insole to minimize migration.

Q3: We are getting inconsistent readings between adjacent sensors in our high-density array. What are the likely causes of this crosstalk?

A: Crosstalk in high-density arrays is a known challenge caused by electrical interference or mechanical coupling [37].

- Electrical Isolation: Implement anti-crosstalk designs in your flexible printed circuit board (PCB). This includes using separate ground lines, shielded traces, and sufficient spacing between sensor electrodes [37].

- Mechanical Decoupling: Use a substrate with appropriate stiffness or design isolated sensing elements to prevent force applied to one sensor from mechanically deforming and affecting its neighbor [37]. Research has successfully used polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) doped with carbon nanotubes to create isolated sensing elements that suppress crosstalk [37].

Q4: What is the minimum number of steps or distance required to obtain reliable plantar pressure data during curved walking experiments?

A: For reliable data in curved walking, the required distance is greater than for linear walking. One study found that to achieve excellent reliability (ICC ≥ 0.90), a minimum distance of 467 meters is recommended for counter-clockwise curved walking, compared to 207 meters for linear walking [7]. Always conduct a reliability analysis for your specific system and protocol to determine the appropriate number of steps.

Frequently Asked Questions on Experimental Protocols

Q1: What are the best practices for calibrating a low-cost FSR insole system to predict metrics like the Center of Pressure (CoP)?

A: A modern approach involves using recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to map data from low-cost sensors to high-fidelity systems [38].

- Data Collection: Simultaneously collect data from your low-cost FSR insole and a gold-standard system (e.g., F-Scan) while subjects perform a variety of activities (standing, walking, turning) [38].

- Virtual Forces: Instead of using raw pressure values, define "virtual forces" in expanded areas around each FSR sensor. This provides a more robust input for the prediction model [38].

- Model Training: Train an RNN model (such as a Long Short-Term Memory network) using the FSR data as input and the CoP/GRF data from the gold-standard system as the target output. RNNs are particularly effective at capturing the time-series nature of gait data [38]. This method has been shown to improve prediction accuracy by more than 30% compared to conventional techniques [38].

Q2: How can I validate the test-retest reliability of my custom-built smart insole system?

A: Follow a standardized test-retest protocol [7]:

- Study Design: Recruit a cohort of participants (e.g., ~30 individuals) to perform two testing sessions, 4-7 days apart.

- Walking Conditions: Include linear walking, clockwise curved walking, and counter-clockwise curved walking to comprehensively assess reliability across different movement patterns.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) for key parameters (Peak Pressure, Pressure-Time Integral, etc.). An ICC > 0.90 is generally considered indicative of excellent reliability. Use Bland-Altman plots and Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) values for further validation [7].

Q3: What key parameters should I extract and analyze from plantar pressure data for clinical gait analysis?

A: Standardize your analysis around a core set of metrics. The following table summarizes essential parameters and their clinical relevance [32] [7]:

Table 1: Key Plantar Pressure Parameters for Gait Analysis